Exploring the Impact of a Family-Focused, Gender-Transformative Intervention on Adolescent Girls’ Well-Being in a Humanitarian Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Setting

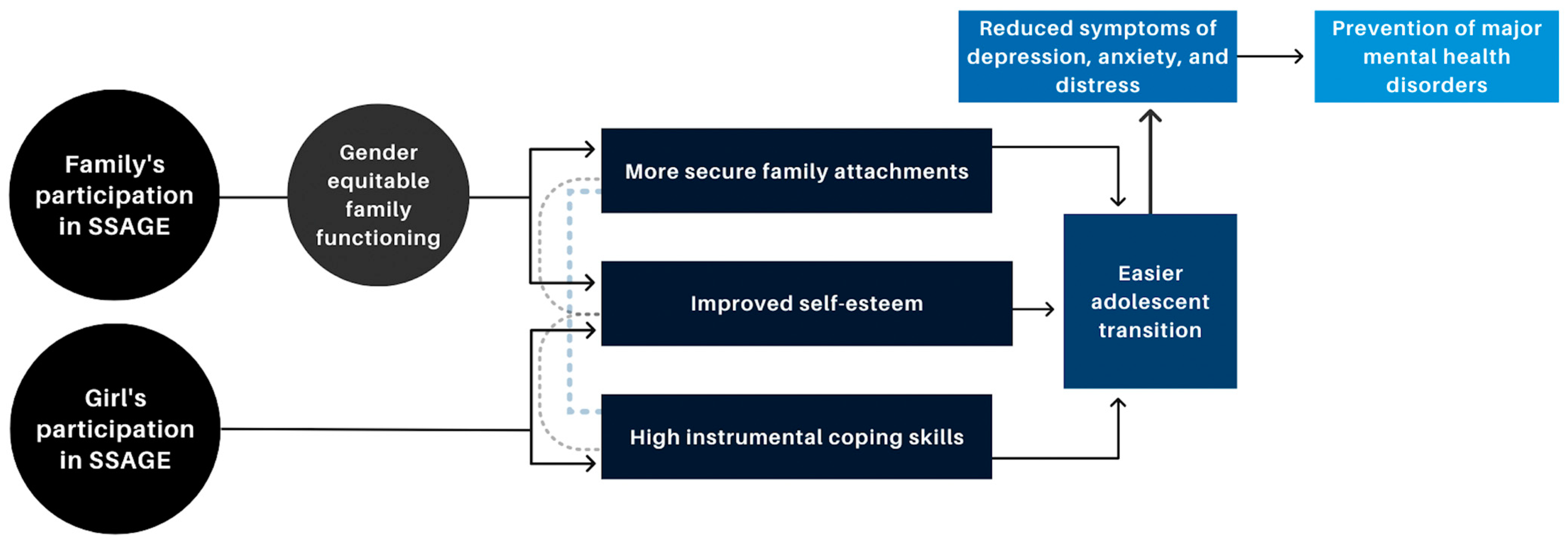

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Quantitative Methods

2.4. Qualitative Methods

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.2.1. Adolescent Girls’ Well-Being

Self-Confidence

Self-Efficacy

“A mother told us that her daughter told her that her brother hit her, rebuked her, and bossed her around all day long. After a while, the mother told me that ‘my daughter benefited from you a lot and she was affected by your personalities a lot. Now when her brother hits her, she will defend herself, because of the information she gets from Mercy Corps.’ I myself learned and gained information and benefited from the teacher a lot”. She defends herself now and she says: “it’s not only you who got information, I did too”.(KII02)

“They taught kids how to be strong and defend themselves when they go out alone, without us. They didn’t know how to, maybe we didn’t give them clear information. Now they can react and defend themselves. A girl knows how to defend her education and future now. Many other things… I wanted my daughter to be stronger. If the program was given again, I would attend the sessions because my daughter benefited. I love to see my daughter strong”.(Azraq-FGD-CF-15022022 (E))

Improved Mental Health

“There was a desperate girl who didn’t feel strong, felt tired most of the time, and spent most of the day alone in her room. She didn’t mingle with people and didn’t sit with her family. She only left her room to eat. She didn’t have anything to talk about with her parents. When Mercy Corps visited the family and told them about the Siblings Program, they agreed to participate in the sessions. They started to attend sessions about self-confidence and self-defense. She started to learn about how to strengthen herself and how to communicate. After the sessions, her life started to become normal, and she started to talk to her parents and speak up her mind. She now tells her family about any problem she faces. She talks to her mom, dad, and brother”.(Za’atari-PAR-AG-20102021(1))

3.2.2. Improvements in Family Members’ Gender Equitable Attitudes and Awareness around Girls’ Safety and Wellbeing among Family Members

“My husband and I for example… he didn’t attend the sessions at first, then he did. The boy used to tell the girl to wash his dishes, and their dad used to tell me to wash the dishes. My son used to tell his sister to prepare the bed for him. After my son participated in the sessions, he started to prepare his bed and wash his dishes. He changed the way he treated his sisters. He is serving himself now. He learnt about compassion and when he sees that his sister or I are sick he will serve himself. His father used to say: ‘is he the girl of the house?’ and that we should serve him. Now things have changed”.(Za’atari-FGD-CF-24102021(2))

3.2.3. Changes in Control of and Communication around Girls’ Mobility and Behaviors

3.2.4. Affective Involvement and Emotional Connection within the Household

“I did not sit with my daughters a lot before. Now I sit with them and talk to them. I feel that a mother should do this. A girl will not tell her mother things if she feels that her mother is distant. When a mother designates time to sit with her daughters, they will communicate more and open up to one another…Yes, there is more harmony now. Anger and sadness are gone. For example, my daughter is not upset with me anymore”.(Azraq-IDI-CF-18102021(1))

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baauw, A.; Holthe, J.K.; Slattery, B.; Heymans, M.; Chinapaw, M.; van Goudoever, H. Health needs of refugee children identified on arrival in reception countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2019, 3, e000516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackmore, R.; Boyle, J.A.; Fazel, M.; Ranasinha, S.; Gray, K.M.; Fitzgerald, G.; Misso, M.; Gibson-Helm, M. The prevalence of mental illness in refugees and asylum seekers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. Report on the Health of Refugees and Migrants in the WHO European Region: No Public Health without Refugee and Migrant Health. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/report-on-the-health-of-refugees-and-migrants-in-the-who-european-region-no-public-health-without-refugee-and-migrant-health (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Scharpf, F.; Kaltenbach, E.; Nickerson, A.; Hecker, T. A systematic review of socio-ecological factors contributing to risk and protection of the mental health of refugee children and adolescents. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 83, 101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akgül, S.; Hüsnü, Ş.; Derman, O.; Özmert, E.; Bideci, A.; Hasanoğlu, E. Mental health of syrian refugee adolescents: How far have we come? Turk. J. Pediatr. 2019, 61, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamford, J.; Fletcher, M.; Leavey, G. Mental Health Outcomes of Unaccompanied Refugee Minors: A Rapid Review of Recent Research. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2021, 23, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, S.; Sadiq, A.; Din, A.U. The Increased Vulnerability of Refugee Population to Mental Health Disorders. Kans J. Med. 2018, 11, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, K.S.; Gillham, J.; DeMaria, L.; Andrew, G.; Peabody, J.; Leventhal, S. Building psychosocial assets and wellbeing among adolescent girls: A randomized controlled trial. J. Adolesc. 2015, 45, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfield, S.; Vertefuille, J.; Mcalpine, D.D. Gender Stratification and Mental Health: An Exploration of Dimensions of the Self. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyranowski, J.M.; Frank, E.; Young, E.; Shear, M.K. Adolescent Onset of the Gender Difference in Lifetime Rates of Major Depression: A Theoretical Model. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2000, 57, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.A.; Meinhart, M.; Samawi, L.; Mukherjee, T.; Jaber, R.; Alhomsh, H.; Kaushal, N.; Al Qutob, R.; Khadra, M.; El-Bassel, N.; et al. Mental health of clinic-attending Syrian refugee women in Jordan: Associations between social ecological risks factors and mental health symptoms. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Pearson, R.J.; McAlpine, A.; Bacchus, L.J.; Spangaro, J.; Muthuri, S.; Muuo, S.; Franchi, G.; Hess, T.; Bangha, M.; et al. Gender-based violence and its association with mental health among Somali women in a Kenyan refugee camp: A latent class analysis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, S.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Hamad, B.A.; Hicks, J.H.; Jones, N.; Muz, J. Do restrictive gender attitudes and norms influence physical and mental health during very young Adolescence? Evidence from Bangladesh and Ethiopia. SSM-Popul. Health 2019, 9, 100480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, C.; Edmeades, J.; Petroni, S.; Kapungu, C.; Gordon, R.; Ligiero, D. Associations between mental distress, poly-victimisation, and gender attitudes among adolescent girls in Cambodia and Haiti: An analysis of Violence Against Children surveys. J. Child. Adolesc. Ment. Health 2019, 31, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, L.; Asghar, K.; Seff, I.; Cislaghi, B.; Yu, G.; Gessesse, T.T.; Eoomkham, J.; Baysa, A.A.; Falb, K. How gender- and violence-related norms affect self-esteem among adolescent refugee girls living in Ethiopia. Glob. Ment. Health 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, J.J.; Sanchez, D.T. Doing Gender for Different Reasons: Why Gender Conformity Positively and Negatively Predicts Self-Esteem. Psychol. Women Q. 2010, 34, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Joiner, T.E.; Kwon, P. Membership in a Devalued Social Group and Emotional Well-Being: Developing a Model of Personal Self-Esteem, Collective Self-Esteem, and Group Socialization. Sex. Roles 2002, 47, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJong, J.; Sbeity, F.; Schlecht, J.; Harfouche, M.; Yamout, R.; Fouad, F.M.; Manohar, S.; Robinson, C. Young lives disrupted: Gender and well-being among adolescent Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Confl. Health 2017, 11 (Suppl. S1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, M.E.; Sterk, C.E.; Hennink, M.; Patel, S.; DePadilla, L.; Yount, K.M. Exploring gender norms, agency and intimate partner violence among displaced Colombian women: A qualitative assessment. Glob. Public Health 2016, 11, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, B.L.; Lu, L.Z.N.; MacFarlane, M.; Stark, L. Predictors of Interpersonal Violence in the Household in Humanitarian Settings: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2020, 21, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, L.; Seff, I.; Reis, C. Gender-based violence against adolescent girls in humanitarian settings: A review of the evidence. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 22Joseph, S. brother/sister relationships: Connectivity, love, and power in the reproduction of patriarchy in Lebanon. Am. Ethnol. 1994, 21, 50–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, A.; Fazel, M.; Bowes, L.; Gardner, F. Pathways linking war and displacement to parenting and child adjustment: A qualitative study with Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 200, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, M.; Muñoz-Laboy, M.; Salamea, E.; Arp, J.; Falb, K.; Rudahindwa, N.; Stark, L. How narratives of fear shape girls’ participation in community life in two conflict-affected populations. Violence against Women 2017, 24, 565–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catani, C.; Jacob, N.; Schauer, E.; Kohila, M.; Neuner, F. Family violence, war, and natural disasters: A study of the effect of extreme stress on children’s mental health in Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry 2008, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saile, R.; Ertl, V.; Neuner, F.; Catani, C. Does war contribute to family violence against children? Findings from a two-generational multi-informant study in Northern Uganda. Child. Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punamäki, R.-L.; Qouta, S.; Miller, T.; El-Sarraj, E. Who Are the Resilient Children in Conditions of Military Violence? Family- and Child-Related Factors in a Palestinian Community Sample. Peace Confl. J. Peace Psychol. 2011, 17, 389–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tol, W.A.; Stavrou, V.; Greene, M.C.; Mergenthaler, C.; van Ommeren, M.; García Moreno, C. Sexual and gender-based violence in areas of armed conflict: A systematic review of mental health and psychosocial support interventions. Confl. Health 2013, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaslow, N.J.; Broth, M.R.; Smith, C.O.; Collins, M.H. Family-based interventions for child and adolescent disorders. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2012, 38, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 30Gillespie, S.; Banegas, J.; Maxwell, J.; Chan, A.; Ali Saleh Darawsha, N.; Wasil, A.; Marsalis, S.; Gewirtz, A. Parenting Interventions for Refugees and Forcibly Displaced Families: A Systematic Review. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khani, A.; Ulph, F.; Peters, S.; Calam, R. Syria: Refugee parents’ experiences and need for parenting support in camps and humanitarian settings. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud. 2018, 13, 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.E.; Ghalayini, H.; Arnous, M.; Tossyeh, F.; Chen, A.; van den Broek, M.; Koppenol-Gonzalez, G.V.; Saade, J.; Jordans, M.J.D. Strengthening parenting in conflict-affected communities: Development of the Caregiver Support Intervention. Glob. Ment. Health 2020, 7, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seff, I.; Steven, S.; Gillespie, A.; Brumbaum, H.; Kluender, H.; Puls, C.; Koris, A.; Akika, V.; Deitch, J.; Stark, L. A Family-Focused, Sibling-Synchronous Intervention in Borno State, Nigeria: Exploring the Impact on Family Functioning and Household Gender Roles. J. Fam. Violence 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Registered Syrians in Jordan. 2019. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/jordan/registered-syrians-jordan-15-october-2019 (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- ‘I Dream of Going Home’: Gendered Experiences of Adolescent Syrian Refugees in Jordan’s Azraq Camp|SpringerLink. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41287-021-00450-9 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Prevention and Response to Sexual and Gender Based Violence (SGBV)—Midyear 2019—Jordan. 2019. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/jordan/prevention-and-response-sexual-and-gender-based-violence-sgbv-midyear-2019 (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Bennouna, C.; Gillespie, A.; Stark, L.; Seff, I. Norms, Repertoires, & Intersections: Towards an integrated theory of culture for health research and practice. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 311, 115351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, S. (Ed.) Arab Family Studies: Critical Reviews; Syracuse University Press: Syracuse, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/j.ctt1pk860c (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Koris, A.; Steven, S.; Akika, V.; Puls, C.; Okoro, C.; Bitrus, D.; Seff, I.; Deitch, J.; Stark, L. Opportunities and challenges in preventing violence against adolescent girls through gender transformative, whole-family support programming in Northeast Nigeria. Confl. Health 2022, 16, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barada, R.; Potts, A.; Bourassa, A.; Contreras-Urbina, M.; Nasr, K. “I Go up to the Edge of the Valley, and I Talk to God”: Using Mixed Methods to Understand the Relationship between Gender-Based Violence and Mental Health among Lebanese and Syrian Refugee Women Engaged in Psychosocial Programming. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barker, P.R.; Colpe, L.J.; Epstein, J.F.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Normand, S.-L.T.; Manderscheid, R.W.; Walters, E.E.; et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebenberg, L.; Ungar, M.; LeBlanc, J.C. The CYRM-12: A Brief Measure of Resilience. Can. J. Public Health 2013, 104, e131–e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panter-Brick, C.; Dajani, R.; Hamadmad, D.; Hadfield, K. Comparing online and in-person surveys: Assessing a measure of resilience with Syrian refugee youth. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2021, 25, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCubbin, H.I.; Thompson, A.I.; Elver, K.M. Family Attachment and Changeability Index 8 (FACI8). In Family Assessment: Resiliency‚ Coping and Adaptation: Inventories for Research and Practice; University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 725–751. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, L.; Asghar, K.; Seff, I.; Yu, G.; Tesfay Gessesse, T.; Ward, L.; Assazenew Baysa, A.; Neiman, A.; Falb, K.L. Preventing violence against refugee adolescent girls: Findings from a cluster randomised controlled trial in Ethiopia. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, A.H.; Asghar, K.; de Dieu Hategekimana, J.; Roth, D.; O’Connor, M.; Falb, K. Family Functioning in Humanitarian Contexts: Correlates of the Feminist-Grounded Family Functioning Scale among Men and Women in the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. J. Child. Fam Stud. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falb, K.; Blackwell, A.; Hategekimana JD, D.; Roth, D.; O’Connor, M. Preventing Co-occurring Intimate Partner Violence and Child Abuse in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo: The Role of Family Functioning and Programmatic Reflections. J. Interpers Violence 2022. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seff, I.; Falb, K.; Yu, G.; Landis, D.; Stark, L. Gender-equitable caregiver attitudes and education and safety of adolescent girls in South Kivu, DRC: A secondary analysis from a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Adolescent Girls | Adolescent Boys | Female Caregivers | Male Caregivers | SSAGE Program Staff and Mentors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle 1 | Azraq | 19 | 16 | 12 | 15 | – |

| Za’atari | 20 | 19 | 17 | 19 | – | |

| Cycle 2 | Azraq | 17 | 16 | 12 | 12 | – |

| Za’atari | 9 | 4 | 3 | 3 | – | |

| Total | 65 | 55 | 44 | 49 | 8 | |

| Full Sample (n = 68) | Adolescent Girls (n = 18) | Adolescent Boys (n = 17) | Female Caregivers (n = 16) | Male Caregivers (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 29.7 [16.2] | 12.5 [2.0] | 16.7 [2.7] | 41.2 [4.0] | 48.6 [7.6] |

| Ever attended school | 66 (97.1%) | 18 (100.0%) | 16 (94.1%) | 15 (93.8%) | 17 (100.0%) |

| Currently attending school (if ever attended) | --- | 18 (100.0%) | 12 (92.3%) | --- | --- |

| Ever worked for pay | 26 (38.2%) | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (4.2%) | 4 (25.0%) | 14 (82.4%) |

| Baseline | Endline | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health | |||

| Kessler Screening Scale for Psychological Distress (n = 55) | 13.67 | 15.85 | 0.007 |

| [5.16] | [6.04] | ||

| Resilience | |||

| Child and Youth Resilience Measure (n = 24) | 39.83 | 42.62 | 0.030 |

| [4.78] | [5.06] | ||

| Gender Equity | |||

| International Men and Gender Equality-modified scale (n = 58) | 2.34 | 2.49 | 0.004 |

| [0.48] | [0.43] | ||

| Family Functioning | |||

| Family Attachment and Changeability Index (n = 52) | 61.33 | 64.69 | 0.044 |

| [8.30] | [10.01] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seff, I.; Koris, A.; Giuffrida, M.; Ibala, R.; Anderson, K.; Shalouf, H.; Deitch, J.; Stark, L. Exploring the Impact of a Family-Focused, Gender-Transformative Intervention on Adolescent Girls’ Well-Being in a Humanitarian Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215357

Seff I, Koris A, Giuffrida M, Ibala R, Anderson K, Shalouf H, Deitch J, Stark L. Exploring the Impact of a Family-Focused, Gender-Transformative Intervention on Adolescent Girls’ Well-Being in a Humanitarian Context. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):15357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215357

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeff, Ilana, Andrea Koris, Monica Giuffrida, Reine Ibala, Kristine Anderson, Hana Shalouf, Julianne Deitch, and Lindsay Stark. 2022. "Exploring the Impact of a Family-Focused, Gender-Transformative Intervention on Adolescent Girls’ Well-Being in a Humanitarian Context" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 15357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215357

APA StyleSeff, I., Koris, A., Giuffrida, M., Ibala, R., Anderson, K., Shalouf, H., Deitch, J., & Stark, L. (2022). Exploring the Impact of a Family-Focused, Gender-Transformative Intervention on Adolescent Girls’ Well-Being in a Humanitarian Context. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215357