Abstract

Recent super-typhoons and torrential rains triggered by global warming have had disproportionately large effects on medically vulnerable people in Japan. This study aimed to identify factors associated with intention to evacuate to the nearest public shelter among family caregivers of pediatric patients receiving home medical care. The study included family caregivers of these patients from the Department of Pediatrics, Fukuoka University Hospital, Japan, including family caregivers of young adults with special healthcare needs. An original questionnaire was prepared drawing on previous studies and used for an interview survey. Overall, 57 individuals provided valid data and were included in the analysis. Factors associated with evacuation intention were non-use of a home ventilator (odds ratio [OR] 3.99, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.13–14.03) and not having made arrangements to use a non-public shelter (OR 7.29 95% CI: 1.62–32.88). This means that those who use mechanical ventilation or have secured alternative places to go if they need to evacuate their homes may not use the nearest public shelter in a disaster. We recommend that policy makers consider the use of mechanical ventilation and the availability of non-public shelters as predictors of evacuation behavior when considering disaster preparedness for these patients.

1. Introduction

Local torrential rain events caused by tropical cyclones fueled by global warming have occurred increasingly often in recent years [1]. Heavy rains from zonal precipitation systems frequently occur in Japan from early summer to autumn, resulting in serious disasters such as landslides, flooding, and mudslides, and causing severe damage [2,3]. This type of torrential rain is reportedly caused by a linear-stationary precipitation system called “Senjo-kousuitai’’ in Japanese [4,5]. These precipitation systems are frequently concentrated in Kyushu, the Nansei Islands, Kii Peninsula, and on the Pacific sides of Shikoku, with fewer appearances in northern Japan and the Sea of Japan side of the Japanese Islands [4]. Since 2000, damage caused by heavy rain occurring as a result of “Senjo-kousuitai” has been observed in northern Kyushu. During the torrential rains in the region in July 2017, more than 40 people were killed [4] and approximately 6000 homes, mainly in Asakura City, lost power for at least 3 days [6]. Prolonged power outages due to natural disasters have a serious impact on older adults and medically vulnerable people [7]. Climate change has also had disproportionate effects on the health of children in recent years [8,9]. These disasters may be life-threatening, especially for children dependent on technology such as mechanical ventilation or suction devices [10]. Prolonged power outages following disasters threaten the lives of these children. The Tohoku region experienced the most extensive blackout after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. The average power outage experienced by children dependent on technology in this instance was 7.8 days, and 55% of them were evacuated to hospital because of the effects of the power outage [11]. Similarly, Gillen et al. found that approximately half of the parents of these children who experienced a power outage called or visited the hospital with the child when the power outage occurred.

Global damage from recent torrential rains and super-typhoons poses a major threat not only to children who are dependent on medical technology but also to medically vulnerable adults, including older adults. Past disasters have shown that treatment for existing or new symptoms that occur after a disaster in medically vulnerable populations is often delayed in the post-disaster period [12]. It is therefore important to ensure that evacuation plans and destinations are prepared, especially for medically vulnerable people.

Previous studies on evacuation intentions found that the willingness to evacuate in the event of a hurricane evacuation order decreases with age [13,14]. Women are also more likely than men to evacuate because they are more aware of the roles of long-term care and incentives for evacuation [15]. A survey of children and families affected by Hurricane Irma in 2017 found that mothers who experienced evacuation, chaos and loss due to Irma were more willing to evacuate again than those who did not [16]. After Hurricane Matthew, it was reported that those with a close-knit community they could rely on during the disaster did not evacuate and stayed with friends and relatives [17]. The presence of children in the home is well known to influence parents’ evacuation decisions [18]. Households with children with disabilities tend to stay in place in the event of a disaster, and do not evacuate even if evacuation is possible [19]. Children with disabilities are more difficult to evacuate from disasters, as are those on ventilators and suction devices. Children with mobility impairments may not be able to squat under their desks during an earthquake, hike hillsides during a flash flood, or run to an evacuation area on high ground in the event of a tsunami [19]. Children with cognitive impairments may also not be able to recognize danger signs or understand imminent threats [20]. To optimize the evacuation of vulnerable groups, it is therefore necessary to identify vulnerable people, mobilize social support such as family and friends, and formulate individual evacuation plans [21].

The Japanese government, following trends in other countries, recommends that any children receiving medical care at home and all older adults should be routinely enrolled with the emergency evacuation assistance registry [22,23,24]. When there is a risk of a disaster, the government classifies the risk by five levels of vigilance, calling for early evacuation of medically vulnerable people and older adults [25].

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted the Japanese government to call for “decentralized evacuation” to the homes of relatives and acquaintances rather than to public shelters, to avoid the risk of infection by indiscriminate crowding and close contact [26,27]. The pandemic has also affected the decision-making of medically vulnerable individuals about evacuation. Fear of COVID-19 may make medically vulnerable people hesitate to evacuate even in disasters where evacuation is essential [22]. A recent survey of willingness to evacuate during hurricanes found that more than half of respondents might not evacuate when there is a hurricane forecast, and 70% of these were concerned about COVID-19 infection [28].

In Japan, the number of pediatric patients with home medical devices is constantly increasing; it was estimated to be 20,000 in 2020 [29]. The importance of building evacuation shelters for vulnerable people has been discussed [30,31], but a system that allows pediatric patients receiving home medical care to evacuate and receive suitable care is still under development. These patients and their families must therefore make their own decisions whether to evacuate to a public shelter in the event of a disaster, and also make their own plans for survival after evacuation. The aim of this study was to determine the factors associated with the intention to evacuate to the nearest public shelter in the event of a disaster among parents with children requiring medical devices or procedures, and visiting the Pediatrics Department of Fukuoka University Hospital, Japan.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Terms Used in Study

2.1.1. Public Shelter

In Japan, local governments designate public shelters, which are facilities where residents can escape the dangers of disasters and live during their evacuation. They publish a list of these public shelters. For example, a list of target areas can be obtained from each municipality’s website [32]. Public shelters include schools and community centers [33], with 92.1% of public schools designated as evacuation centers [34]. However, there may be problems with using public shelters. For example, after the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, a large number of victims were forced to live in evacuation shelters for a long period of time, resulting in a decline in mental and physical function and illness [33].

2.1.2. Welfare Shelter

In Japan, facilities to which vulnerable people can evacuate are called welfare shelters. Local governments require existing facilities for older adults to set up shelters separate from the public shelters to provide space for older adults, children, and medically vulnerable people who need to evacuate their homes [31,35].

2.1.3. Pediatric Patients Receiving Home Medical Care

We included children aged ≤15 years requiring home medical care and patients with healthcare transition needs [36] visiting pediatric departments, i.e., adults with special healthcare needs [37,38].

2.2. Data Collection

The study included family caregivers of pediatric patients receiving home medical care who were receiving care on an outpatient basis from Fukuoka University Hospital. Family caregivers included caregivers of adults with special healthcare needs who continued to receive treatment in pediatric departments. The survey method was an interview survey carried out in conversation with one of two nurses (one researcher and one outpatient nurse). To ensure consistency, we explained the content of the survey to the outpatient nurse, who also received training in listening. Participants were 57 family caregivers of these outpatients drawn from the Pediatrics Department of Fukuoka University Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan. The sample selection used non-probabilistic sampling. Fukuoka University Hospital has the largest perinatal maternal and child medical center in western Japan, accepts most of the relevant patients for this study, especially from western Japan, and provides ongoing treatment and family support for premature babies and children with congenital diseases [39,40]. Before starting the survey, participants were asked to read information about the purpose of the survey and the confidentiality policy and provide written informed consent.

For the survey, we developed a questionnaire-based interview survey that assessed the preparedness of family caregivers of these patients for disasters, the hazards assumed at their place of residence, knowledge required for evacuation, and willingness to evacuate. The questionnaire development was based on studies by Tanaka [41] and Nakagawa et al. [42] on disaster preparation and plans for Japanese children with severe disabilities. The survey was conducted from 26 May 2021 to 22 December 2021.

2.3. Survey Content

2.3.1. Background Information about Pediatric Patients Requiring Home Medical Care

The survey asked about the children’s age, number of cohabitants, sex and diagnosis.

2.3.2. Medical Devices and Procedures

The survey was used to collect information about the use of mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, oxygen inhalation, suctioning, tube feeding, urethral catheterization, blood glucose measurement, nasotracheal airway, central venous nutrition, inhalation, and mechanically assisted coughing.

2.3.3. Family Caregiver Background

We also sought information about the family caregiver, including age, sex, employment status (regular or non-regular employment; Yes/No), and previous experience of evacuation during a disaster (Yes/No).

2.3.4. Preparation in the Event of a Disaster

Items about whether the caregiver was prepared for disaster included whether they had prepared children’s clothing, food, equipment and medication for the patient, and if they had secured a power supply to ensure that they could continue to use medical devices in the event of a power outage. These were all answered “Yes/No”.

2.3.5. Destination of, Preparation for, and Intention to Evacuate

Questions about whether the caregiver had arranged an evacuation site other than general shelters, and intention to evacuate to welfare shelters were answered “Yes/No”. A question about whether they were mentally prepared for evacuation life had answer options of “Yes”, “Somewhat”, “Not really” and “No”, and whether they had requested help for evacuation support and registered with the ledger on support required in the event of a disaster held by the local government were answered “Yes/No”.

2.3.6. Knowledge of Welfare Shelters, Decentralized Evacuation

We asked whether the caregiver knew the location of a designated shelter, about welfare shelters, the location of a welfare shelter, and the proposal for decentralized evacuation, all of which were answered “Yes/No”.

2.3.7. Disaster Risk in Residential Areas

Finally, we asked whether they knew about the risk of river flooding, landslides, and tsunami flooding in the area of their residence.

2.4. Analytical Methods

The analysis included 57 people who provided complete and valid answers to all items related to the background of the patient and family caregiver, medical devices and procedures required for the patient, preparedness for disasters, destination, preparation and intention of evacuation, knowledge of welfare shelters, knowledge about decentralized evacuation, and disaster risk in their area of residence.

To understand the characteristics of the participants, we assessed the median age (and range) of the patients. The distribution of age of the family caregivers was also determined. We also examined the distribution of medical devices used by and medical procedures required by patients.

To evaluate the factors affecting intention to evacuate to a designated shelter, patients were divided into two groups by age (under or over 15 years of age) to fit the definition used in pediatric care in Japan [43]; by whether they lived with more or fewer than four cohabitants (using the number of people per household in the 2020 census) [44]; and by whether the family caregiver was under or over 30. We then examined the relationship between each factor and intention to evacuate [13,14]. We used the χ2 test or Fisher’s direct probability test to determine the relationship between intention to evacuate to a public shelter and the background of the patient and family caregiver, medical devices and procedures required, preparedness in case of a disaster, intention and plan for evacuation in case of a disaster, request for evacuation support, and mental preparation for evacuation life. To evaluate the impact of the pediatric patients’ use of medical devices, necessary medical procedures, disaster preparedness, request for support in a disaster, and preparedness for evacuation life on intention to evacuate to designated shelters, we used the following methods. Age classification of the patient and experience of disaster by the family caregiver [16,45] were entered by forced entry. Items with significance of p < 0.05 in the univariate analysis, i.e., working status of the caregiver, use of ventilators, arranging an evacuation site other than the designated shelter, and number of cohabitants, were analyzed in a stepwise binomial logistic regression analysis. Each variable was entered after checking multiple collinearities (variance inflation factor ≥ 10). The significance level was set at 5%. SPSS Ver27 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, 1995 (as revised in Seoul, 2008) and carried out with the consent of the university medical research ethics review committees at the authors’ universities (U21-04-010, I469). Participants were given written and verbal explanations of informed consent. They received an explanation of the purpose and importance of the survey, the survey method, voluntary participation, and the anonymity of participants’ responses, and agreed to sign a consent form.

3. Results

Overall, 89 people agreed informally to cooperate with the survey, but the risk of infection due to COVID-19 meant that 32 of them gave up the interview survey because they postponed medical examinations or switched to online consultations. Responses were obtained from 57 people who continued to visit the hospital on an outpatient basis during the COVID-19 pandemic (64.0% response rate). The data of 57 participants (64.0%) were therefore included in the analysis.

The median (range) age of the pediatric patients was 7 (0–46) years, 48 (84.2%) were under 15 years old, and nine (15.8%) were 15 years old or older. In total, 29 (50.9%) were male and 28 (49.1%) were female, and the number of cohabitants was four or more for 41 (71.9%) and fewer than four for 16 (28.1%) participants.

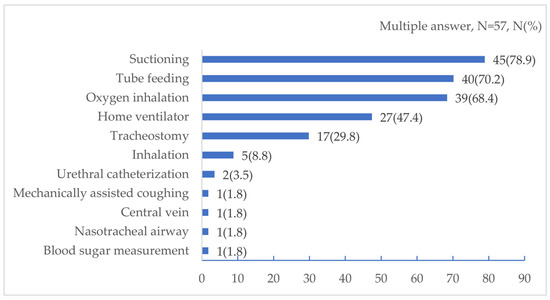

Respondents could choose multiple answers for the medical devices and procedures required for the patients. Overall, 47 patients (78.9%) required tracheal suctioning, 40 (70.2%) required tube feeding, and 39 (68.4%) oxygen inhalation. Figure 1 shows the medical devices and procedures required by these patients.

Figure 1.

Medical devices and procedures required by the pediatric patients in this study.

Overall, 54 family caregivers (94.7%) were in their thirties or older, and three (5.3%) were in their twenties or younger. A total of 56 (98.2%) were women and one (1.8%) was a man; 20 (35.1%) were working, of whom 11 (19.3%) were non-regular employees and nine (15.8%) were regular employees. Five (8.8%) had experienced a disaster in the past (Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic attributes, disaster preparedness, and intention to evacuate to a public shelter, by intention to evacuate (N = 57).

The most common items for disaster preparedness included a power supply for continuing use of medical devices during power outages (available to 35, 61.4%), food for the patients (18, 31.6%), and medical hygiene materials (16, 28.1%). A total of 25 (43.9%) respondents said that they would evacuate to a designated shelter and 47 (82.5%) that they would evacuate to a welfare shelter. Overall, 25 (43.9%) were registered with the support ledger of the local government, 20 (35.1%) had secured evacuation sites other than general evacuation centers, 19 (33.3%) had requested help from others to provide evacuation support, and nine (15.8%) had planned for life after evacuation. Knowledge of welfare shelters and decentralized evacuation was as follows: 51 (89.5%) knew the location of the designated shelter, 21 (36.8%) knew that the government had called for decentralized evacuation, 11 (19.3%) knew about welfare shelters, and two (3.5%) knew the location of a welfare shelter. In terms of risk of disaster in residential areas, 46 (80.7%) were aware of the risk of river flooding, and 42 (73.7%) about the risk of landslides and tsunami flooding (Table 1).

Among the respondents, the 27 people (65.9%) (p = 0.018) who lived with at least four cohabitants, the 19 (70.4%) (p = 0.04) whose patient used a home respirator, and the 15 (75.0%) (p = 0.035) who had arranged an evacuation site other than the general shelter were significantly more likely to respond that they were not intending to evacuate to a designated shelter.

A binomial logistic regression analysis was performed on factors associated with intention to evacuate to a designated shelter. The factors associated with the intention of evacuating children receiving home medical care to a public shelter were non-use of a home ventilator (OR 3.99, 95% CI: 1.13–14.03), and not having arranged an evacuation site other than the designated shelter (OR 7.29 95% CI: 1.62–32.88) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors associated with evacuation intention: age, parents’ evacuation experience, use of home mechanical ventilation, and securing evacuation sites other than a public shelter.

4. Discussion

Of the children receiving home medical care who participated in this study, 15.8% were young adults with special healthcare needs. The number of patients in healthcare transitions requiring special medical care is increasing, and the collaboration between pediatrics and other clinical departments is progressing [46]. According to a 2016 survey of five hospitals in Japan, the proportion of young adults with special healthcare needs aged 14 years or older attending the hospital ranged from 11.4% to 21.6%, suggesting that the percentage of young adults with special healthcare needs in this study [47] was typical.

According to a previous study in Japan, the gender distribution of pediatric patients with special healthcare needs was about 52% male and 46% female, with an average age (standard deviation) of 7.8 (5.5) years [48]. According to a survey by Kitakyushu, the median age of fathers and mothers of pediatric patients with special healthcare needs was 40 years old, and 42.7% of mothers worked [49]. The pediatric patients in this study were 50.9% male, the median age was 7 years old, 94.7% of family caregivers were 30 years old or older, and 35.1% were working. It is therefore likely that the participants of this study were reasonably representative of the overall study population. A nationwide survey by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare found that 74.4% of pediatric patients with special healthcare needs used tube feeding, 69.0% suctioning, 41.8% endotracheal intubation/tracheostomy, 40.1% inhalation, 37.5% oxygen inhalation, and 33.0% home ventilators [50]. In this study, tube feeding and suctioning were the most frequent needs of patients, followed by oxygen inhalation. Considering the differences in target age, survey content, and survey methods, it is possible that the distribution of privately-used medical devices and medical procedures followed a similar pattern to the national survey.

Overall, 56.1% of family caregivers of pediatric patients receiving home medical care were not intending to evacuate to a public shelter. Family caregivers of children using ventilators may be less likely to evacuate than those of children who do not use this equipment. The results are consistent with a previous study of power-dependent home care patients in Japan [51]. In the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of 1995, families with severely disabled children temporarily evacuated to public shelters, but many were forced to leave the public shelters and stay at relatives’ homes, and evacuate the child to hospital. Some families even had to live in their cars because (1) they required a variety of specialized resources and (2) children with intellectual disabilities showed a variety of behavioral problems. Some families were forced to evacuate by car [52]. This situation was similar after the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, when children using mechanical ventilation sought refuge in cars instead of public shelters [53]. Even in the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake, those who needed medical attention gave up going to a shelter out of fear of causing inconvenience to others and to avoid difficulties in continuing care because of lack of private space [54]. Ventilator users may therefore have judged that they would not be able to function in a public shelter. However, 82.5% of family caregivers in this study said they would evacuate to a welfare shelter. In Japan, welfare shelters are shelters for old, disabled, and medically vulnerable people in the event of a disaster. They are installed in existing facilities for older adults and people with disabilities [35]. However, there are no doctors or nurses on the premises because these are not medical facilities. They also have existing residents. In the Kumamoto earthquake, welfare shelters were available, but there were no additional staff available to care for the temporary shelter-seekers because of the disaster-related shortage of nursing care workers [55]. The current system of welfare shelters therefore has significant flaws, and there may not be sufficient capacity to provide adequate care for medically vulnerable people who safely evacuate to a welfare shelter. A survey after the Great East Japan Earthquake revealed that emergency plans for disaster preparedness in welfare shelters, including staffing, cooperation with medical professionals [56], and accommodation for the diverse needs of pediatric patients receiving home medical care and older adults were all lacking [53]. However, the high willingness of family caregivers in this study to evacuate to welfare shelters may suggest that they have higher expectations of welfare shelters than public shelters, without fully understanding the characteristics and challenges of welfare shelters.

This study had several limitations. First, the participants were family caregivers of pediatric patients receiving home medical care and care on an outpatient basis at one university hospital in Fukuoka Prefecture, and sample size calculations were not performed. We could not control for the effect of the sex of family caregivers, a potential confounding factor, because this study prioritized collecting data on the children, rather than caregivers. Survey results can also be influenced by their timing, in this case perhaps by whether there had been a recent disaster. It is possible that there were more vulnerable participants among the 32 who were unable to participate in the study because of fears of exposure to COVID-19. No comparison was made from before the COVID-19 pandemic, and we therefore do not know the impact of the pandemic on people’s intention to evacuate. It is also possible that the presence or absence of power dependence affected evacuation intention. Given these limitations, the results of this study cannot be generalized. Family caregivers of relatively new patients, or who only recently began living with the patient, might also have been less likely to respond to the survey because they already felt under pressure. This would mean that family caregivers who were more experienced and used to living with their patient’s needs may have been over-represented in our sample. To increase reliability, future studies should carry out sample size calculations, increase the number of participants, and measure internal consistency using the reliability coefficient. Finally, this study had a cross-sectional design and it is therefore not possible to establish any causal relationships between the variables under investigation.

5. Conclusions

University hospital staff and municipal policy makers should be aware that family caregivers of pediatric patients receiving home medical care who use ventilators may not evacuate to public shelters even if they are opened. Estimated evacuation rates of these patients to public shelters may therefore not accurately predict actual evacuation rates. It is recommended that staff check if family caregivers of these patients have secured other evacuation sites beforehand, and that their arranged evacuation sites will be suitable. In particular, many children using medical devices such as mechanical ventilators may have judged that it will be difficult to continue mechanical ventilation in public shelters. Considering the current challenges of Japanese welfare shelters, we recommend considering the installation of a new evacuation shelter dedicated to the evacuation of pediatric patients requiring mechanical ventilation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M. (Yukari Matsumoto) and H.N.; Methodology, Y.M. (Yukari Matsumoto), T.H. and H.N.; Formal analysis, Y.M. (Yukari Matsumoto) and H.N.; Investigation, Y.M. (Yukari Matsumoto) and Y.K.; Resources, Y.M. (Yukari Matsumoto), T.H., Y.K. and H.N.; Data curation, Y.K. and H.N.; Writing—original draft preparation, Y.K. and H.N.; Writing—review and editing, Y.M. (Yukari Matsumoto), H.N., Y.K., T.H. and Y.M. (Yumiko Miyagi); Supervision, H.N. and Y.M. (Yumiko Miyagi), Project administration, Y.K. and H.N.; Funding acquisition, Y.M. (Yukari Matsumoto). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by KAKENHI JSPS [19K11106].

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, 1995 (as revised in Seoul, 2008) and carried out with the consent of the university medical research ethics review committees at the authors’ universities (U21-04-010), (I469).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Melissa Leffler, for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yamada, Y.; Satoh, M.; Sugi, M.; Kodama, C.; Noda, A.T.; Nakano, M.; Nasuno, T. Response of Tropical Cyclone Activity and Structure to Global Warming in a High-Resolution Global Nonhydrostatic Model. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 9703–9724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T. Quasi-Stationary Band-Shaped Precipitation Systems, Named “Senjo-Kousuitai”, Causing Localized Heavy Rainfall in Japan. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 2020, 98, 485–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Meteorological Agency Commentary on “Senjo-Kousuitai”. Available online: https://www.jma.go.jp/jma/kishou/know/bosai/kishojoho_senjoukousuitai.html (accessed on 8 August 2022). (In Japanese).

- Hirockawa, Y.; Kato, T.; Tsuguti, H.; Seino, N. Identification and Classification of Heavy Rainfall Areas and Their Characteristic Features in Japan. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 2020, 98, 835–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasaki, Y.; Yoshizaki, M.; Suzuki-Parker, A.; Watarai, Y. Sensitivity of Quasi-Stationary Band-Shaped Precipitation System to Topography: A Case Study for 28 August 2008 Okazaki Heavy Rainfall Event. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 2019, 97, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyushu Electric Power Co., Inc. Results of Response to Disasters. Available online: https://www.kyuden.co.jp/company_history_energy_disaster_disaster.html (accessed on 9 August 2022). (In Japanese).

- Dugan, J.; Byles, D.; Mohagheghi, S. Social Vulnerability to Long-Duration Power Outages. 2022. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4172862 (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Stanberry, L.R.; Thomson, M.C.; James, W. Prioritizing the Needs of Children in a Changing Climate. PLOS Med. 2018, 15, e1002627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderko, L.; Chalupka, S.; Du, M.; Hauptman, M. Climate Changes Reproductive and Children’s Health: A Review of Risks, Exposures, and Impacts. Pediatr. Res. 2020, 87, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barfield, W.D.; Krug, S.E.; Watterberg, K.L.; Aucott, S.W.; Benitz, W.E.; Eichenwald, E.C.; Goldsmith, J.P.; Hand, I.L.; Committee on Fetus and Newborn; Disaster Preparedness Advisory Council; et al. Disaster Preparedness in Neonatal Intensive Care Units. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20170507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, T.; Tanaka, S.; Uematsu, M.; Kikuchi, A.; Hino-Fukuyo, N.; Morimoto, T.; Sakamoto, O.; Tsuchiya, S.; Kure, S. Effect of a Blackout in Pediatric Patients with Home Medical Devices during the 2011 Eastern Japan Earthquake. Brain Dev. 2014, 36, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runkle, J.D.; Brock-Martin, A.; Karmaus, W.; Svendsen, E.R. Secondary Surge Capacity: A Framework for Understanding Long-Term Access to Primary Care for Medically Vulnerable Populations in Disaster Recovery. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, e24–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazo, J.K.; Bostrom, A.; Morss, R.E.; Demuth, J.L.; Lazrus, H. Factors Affecting Hurricane Evacuation Intentions. Risk Anal. 2015, 35, 1837–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumbo, C.; Meyer, M.A.; Marlatt, H.; Peek, L.; Morrissey, B. An Assessment of Change in Risk Perception and Optimistic Bias for Hurricanes Among Gulf Coast Residents. Risk Anal. 2014, 34, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, J.M.; Edwards, B. Gender and Evacuation: A Closer Look at Why Women Are More Likely to Evacuate for Hurricanes. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2002, 3, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodar, K.E.; La Greca, A.M.; Tarlow, N.; Comer, J.S. “My Kids Are My Priority”: Mothers’ Decisions to Evacuate for Hurricane Irma and Evacuation Intentions for Future Hurricanes. J. Fam. Issues 2020, 41, 2251–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.; Ersing, R.; Polen, A. Evacuation Decision-Making during Hurricane Matthew: An Assessment of the Effects of Social Connections. Weather Clim. Soc. 2017, 9, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, N.; Gladwin, H. Evacuation Decision Making and Behavioral Responses: Individual and Household. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2007, 8, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, L.; Stough, L.M. Children with Disabilities in the Context of Disaster: A Social Vulnerability Perspective. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 1260–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kailes, J.I.; Enders, A. Moving Beyond “Special Needs”: A Function-Based Framework for Emergency Management and Planning. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 2007, 17, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, H.S.; Grace, R. Influence of Social Networks and Opportunities for Social Support on Evacuation Destination Decision-Making. Saf. Sci. 2022, 147, 105564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whytlaw, J.L.; Hutton, N.; Yusuf, J.-E.; Richardson, T.; Hill, S.; Olanrewaju-Lasisi, T.; Antwi-Nimarko, P.; Landaeta, E.; Diaz, R. Changing Vulnerability for Hurricane Evacuation during a Pandemic: Issues and Anticipated Responses in the Early Days of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 61, 102386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renne, J.L.; Mayorga, E. What Has America Learned Since Hurricane Katrina? Evaluating Evacuation Plans for Carless and Vulnerable Populations in 50 Large Cities across the United States. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 80, 103226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Office Measures for People Vulnerable to Disasters. Available online: https://www.bousai.go.jp/taisaku/hisaisyagyousei/youengosya/index.html (accessed on 12 September 2022). (In Japanese).

- Japan Meteorological Agency Correspondence between Weather Information and Warning Levels. Available online: https://www.jma.go.jp/jma/kishou/know/bosai/alertlevel.html (accessed on 12 September 2022). (In Japanese).

- Takaoka, S.; Kawata, Y.; Kai, T. A Study of Issues Related to the Operation of Evacuation Shelters in a Corona-Endemic Society—Through the Guidelines and Training of Shiga Prefecture in Japan. J. Disaster Res. 2021, 16, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Office 2021 White Paper on Disaster Prevention, Measures for Shelters Based on the Infection Status of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.bousai.go.jp/kaigirep/hakusho/r03/honbun/0b_1s_01_01.html (accessed on 12 September 2022). (In Japanese).

- Old Dominion University Life in Hampton Roads Survey: Hurricanes and COVID-19. Available online: http://www.odu.edu/news/2020/8/lihr_hurricanes_and_ (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Trends in Policies for Special Healthcare Needs Children. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10800000/000584473.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2022). (In Japanese)

- Karaye, I.M.; Thompson, C.; Horney, J.A. Evacuation Shelter Deficits for Socially Vulnerable Texas Residents During Hurricane Harvey. Health Serv. Res. Manag. Epidemiol. 2019, 6, 2333392819848885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kako, M.; Steenkamp, M.; Ryan, B.; Arbon, P.; Takada, Y. Best Practice for Evacuation Centres Accommodating Vulnerable Populations: A Literature Review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 46, 101497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuoka City List of Evacuation Sites and Public Shelters. Available online: https://www.city.fukuoka.lg.jp/bousai/shiteihinannbasyooyobishiteihinannjyoitirann.html (accessed on 15 October 2022). (In Japanese).

- Cabinet Office 2015 Disaster Prevention White Paper, Evacuation Site/Public Shelter. Available online: https://www.bousai.go.jp/kaigirep/hakusho/h27/honbun/1b_1s_02_02.html (accessed on 8 August 2022). (In Japanese).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Investigation on Disaster Prevention Functions of Public Schools That Serve as Evacuation Shelters, as of 1 April 2017. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shisetu/bousai/1394437.htm (accessed on 12 September 2022). (In Japanese).

- Cabinet Office Revision of Guidelines for Securing and Operating Welfare Shelters, May 2021. Available online: https://www.bousai.go.jp/taisaku/hinanjo/r3_guideline.html (accessed on 11 September 2022).

- Schmidt, A.; Ilango, S.M.; McManus, M.A.; Rogers, K.K.; White, P.H. Outcomes of Pediatric to Adult Health Care Transition Interventions: An Updated Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 51, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Pediatric Society Recommendations for Transitional Care for Patients with Childhood-Onset Diseases, Japan Pediatric Society. Available online: http://www.jpeds.or.jp/modules/guidelines/index.php?content_id=54 (accessed on 18 September 2022). (In Japanese).

- White, P.H.; Cooley, W.C.; Boudreau, A.D.A.; Cyr, M.; Davis, B.E.; Dreyfus, D.E.; Forlenza, E.; Friedland, A.; Greenlee, C.; Mann, M.; et al. Supporting the Health Care Transition from Adolescence to Adulthood in the Medical Home. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20182587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Perinatal Maternal and Child Medical Care Center, F.U.H. General Perinatal Maternal and Child Medical Care Center, Fukuoka University Hospital. Available online: https://www.hop.fukuoka-u.ac.jp/center/04/ (accessed on 15 October 2022). (In Japanese).

- Fukuoka University Hospital. Available online: https://www.hop.fukuoka-u.ac.jp/eng/ (accessed on 31 August 2022). (In Japanese).

- Tanaka, S. Severe mental and physical disability medical care at the time of disaster—Problems and countermeasures in the event of a disaster, preparation in advance. Jpn. J. Pediatr. Med. 2015, 47, 1894–1898. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Kitamura, Y.; Yoneyama, A.; Kato, K. Awareness of disaster prevention among families of children with severe physical and mental disabilities living in the Tokyo metropolitan area—Degree of recognition of welfare shelter, intention to evacuate, demands to live in an evacuation shelter. J. Child Health 2016, 75, 621–628. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Regarding pediatric medical care. In Proceedings of the 17th Meeting on the Review of Medical Plans; Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10800000/000584472.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2022). (In Japanese).

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Japan Summary of 2020 Census Population Results. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/data/kokusei/2020/kekka/pdf/outline_01.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021). (In Japanese)

- Vásquez, W.F.; Murray, T.J.; Mozumder, P. Understanding Hurricane Evacuation Planning in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic United States. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2016, 17, 04015018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, S.R.; Kuhlthau, K.; Van Cleave, J.; Knapp, A.A.; Newacheck, P.; Perrin, J.M. Health Care Transition for Youth with Special Health Care Needs. J. Adolesc. Health 2012, 51, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, H. Childhood Chronic Specified Disease Child Adult Transitional Medical Support Model Project (Document 2). Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-12601000-Seisakutoukatsukan-Sanjikanshitsu_Shakaihoshoutantou/0000170303.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022). (In Japanese).

- Kumode, M.; Hoshino, R.; Sato, S.; Matsubasa, T.; Nagae, A.; Fujita, Y. Fact-Finding Survey of Children with Advanced Special Healthcare Needs. J. Jpn. Soc. Pediatr. Surg. 2018, 22, 1519–1526. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Araki, S.; Nakamura, K.; Kashiwabara, Y.; Eguchi, H.; Shimono, M. A Field Survey of Working Conditions of Parents with Children Requiring Medical Care. J. UOEH 2019, 41, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Report of a Survey on the Actual Situation Regarding the Lives of Patients with Special Healthcare Needs and Family Caregivers at Home. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/12200000/000653544.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022). (In Japanese)

- Nakai, H.; Tsukasaki, K.; Kyota, K.; Itatani, T.; Nihonyanagi, R.; Shinmei, Y.; Yasuoka, S. Factors Related to Evacuation Intentions of Power-Dependent Home Care Patients in Japan. J. Community Health Nurs. 2016, 33, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takada, S. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders and Mental Health Care (Lessons Learned from the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, Kobe, 1995). Brain Dev. 2013, 35, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S. Issues in the Support and Disaster Preparedness of Severely Disabled Children in Affected Areas. Brain Dev. 2013, 35, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasugi, T.; Umeyama, G.; Shimazaki, K.; Yokoyama, Y.; Haraoka, T.; Ikeda, M.; Okada, E.; Ojima, T. Issues and Countermeasures Regarding Disaster Response in the Healthcare and Welfare Fields for Persons Requiring Special Care and Consideration in the Kumamoto Earthquake: Through Qualitative Research. J. Natl. Inst. Public Health 2020, 69, 296–305. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, J.; Nakano, S. Survey on Theactual Conditons of Welfare Evacuation Shelthers in the Kumamoto Earthquake. J. Geol. Eng. F6 2018, 74, I_131–I_136. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knai, J.; Nakano, S.; Nonomura, A.; Uno, K. Conduct Survey about Evacuation Center for Vulnerable People in Shikoku Area. J. Geol. Eng. F6 2016, 72, I_145–I_150. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).