PREVIDE: A Qualitative Study to Develop a Decision-Making Framework (PREVention decIDE) for Noncommunicable Disease Prevention in Healthcare Organisations

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To (a) explore and (b) compare decision-making in two healthcare organisations (clinical and public health) for NCD prevention using a qualitative approach and Queensland, Australia as the use case setting.

- To develop a contemporary decision-making framework for NCD prevention in healthcare organisations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Stage One—Unsupervised Machine Learning

2.5.2. Stage Two—Researcher-Led Interpretation

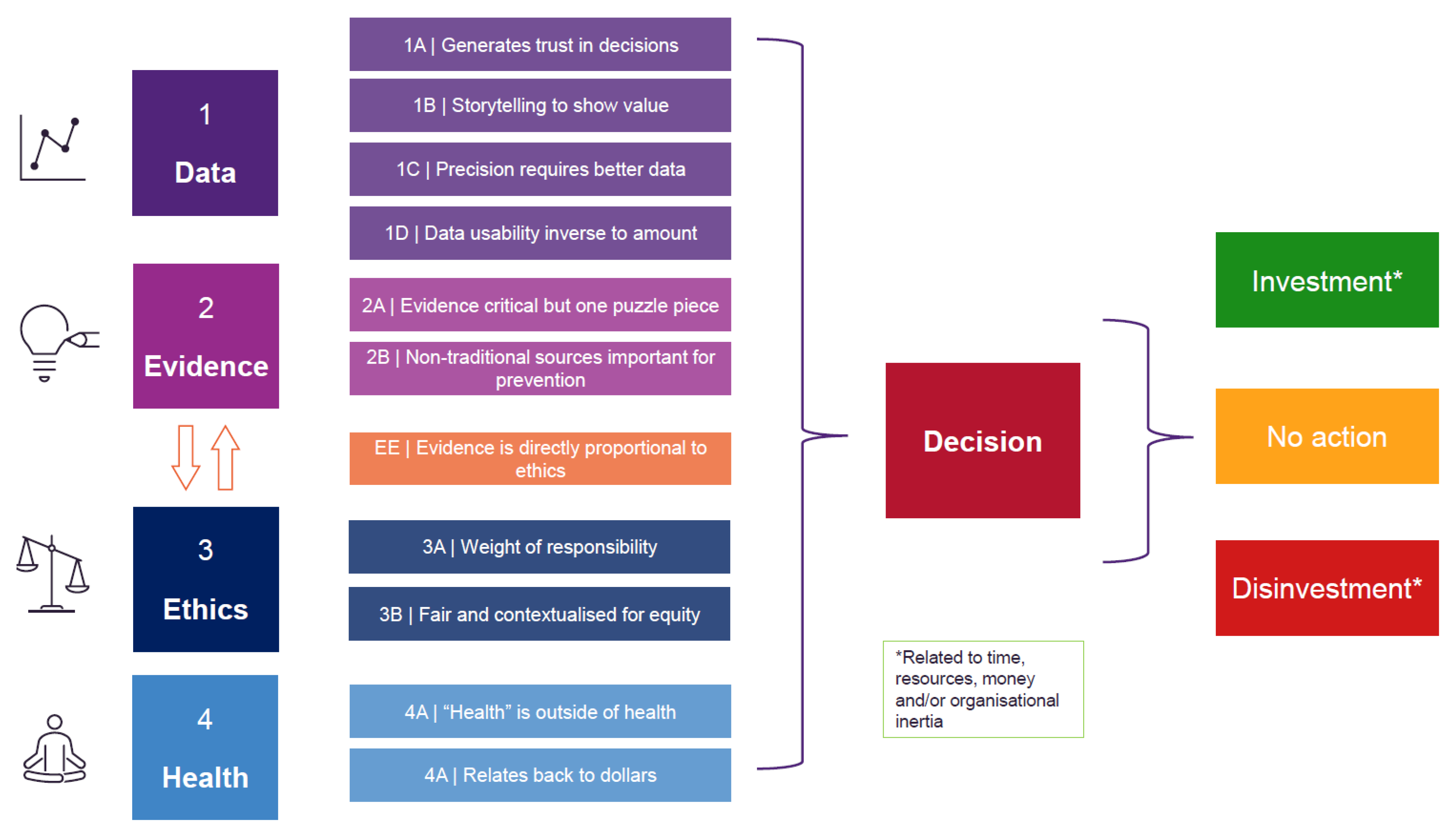

2.5.3. Developing the Decision-Making Framework

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

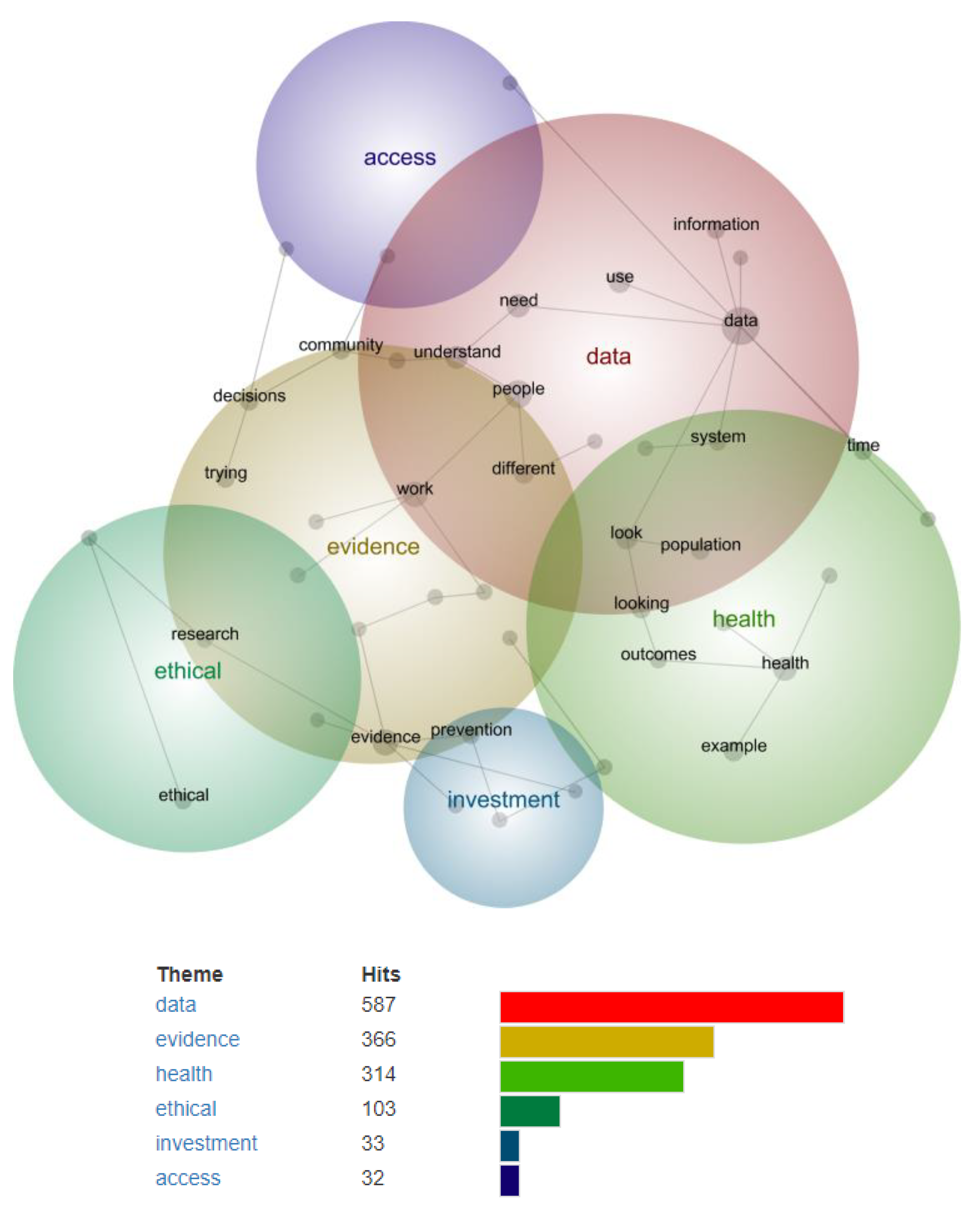

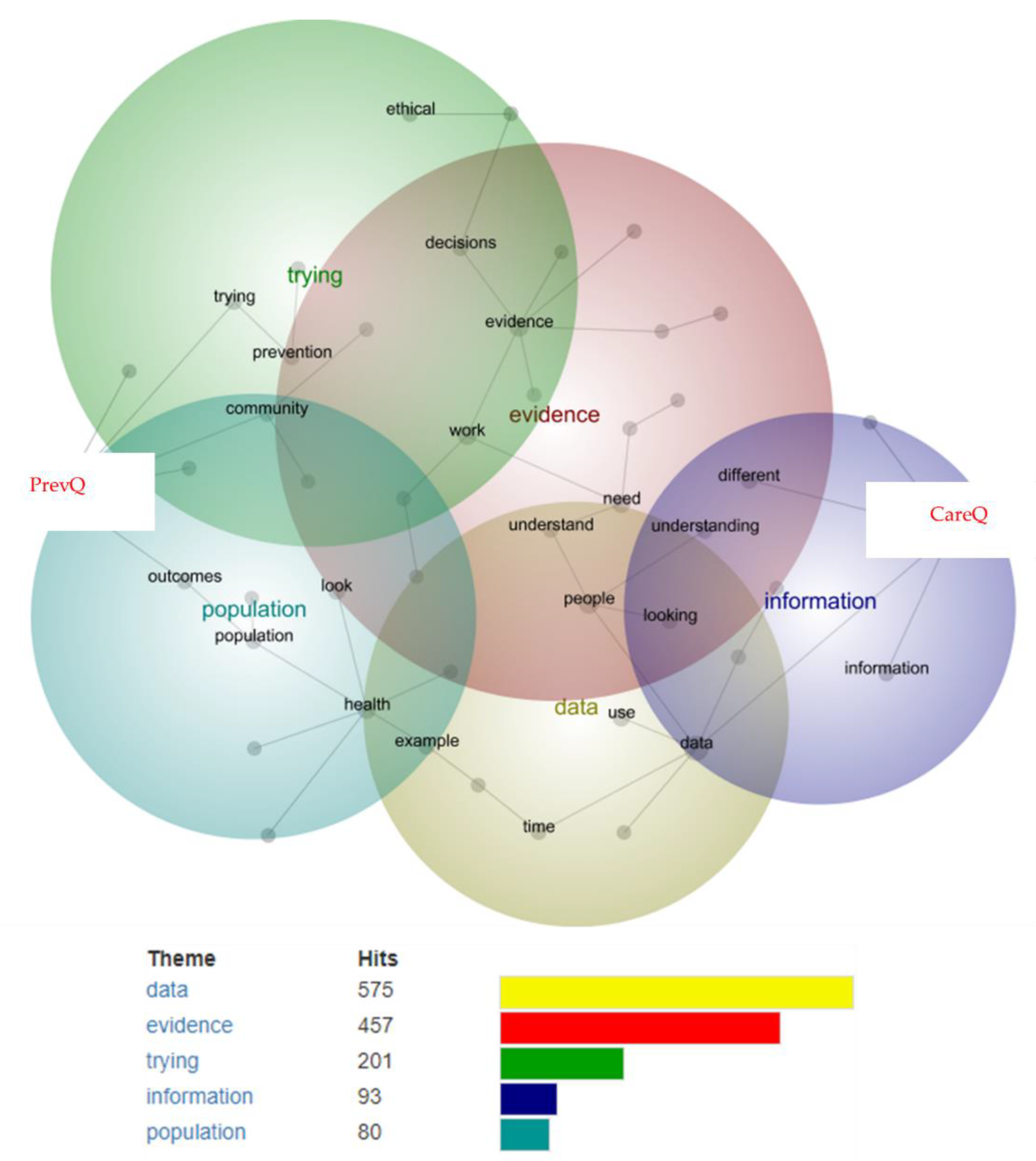

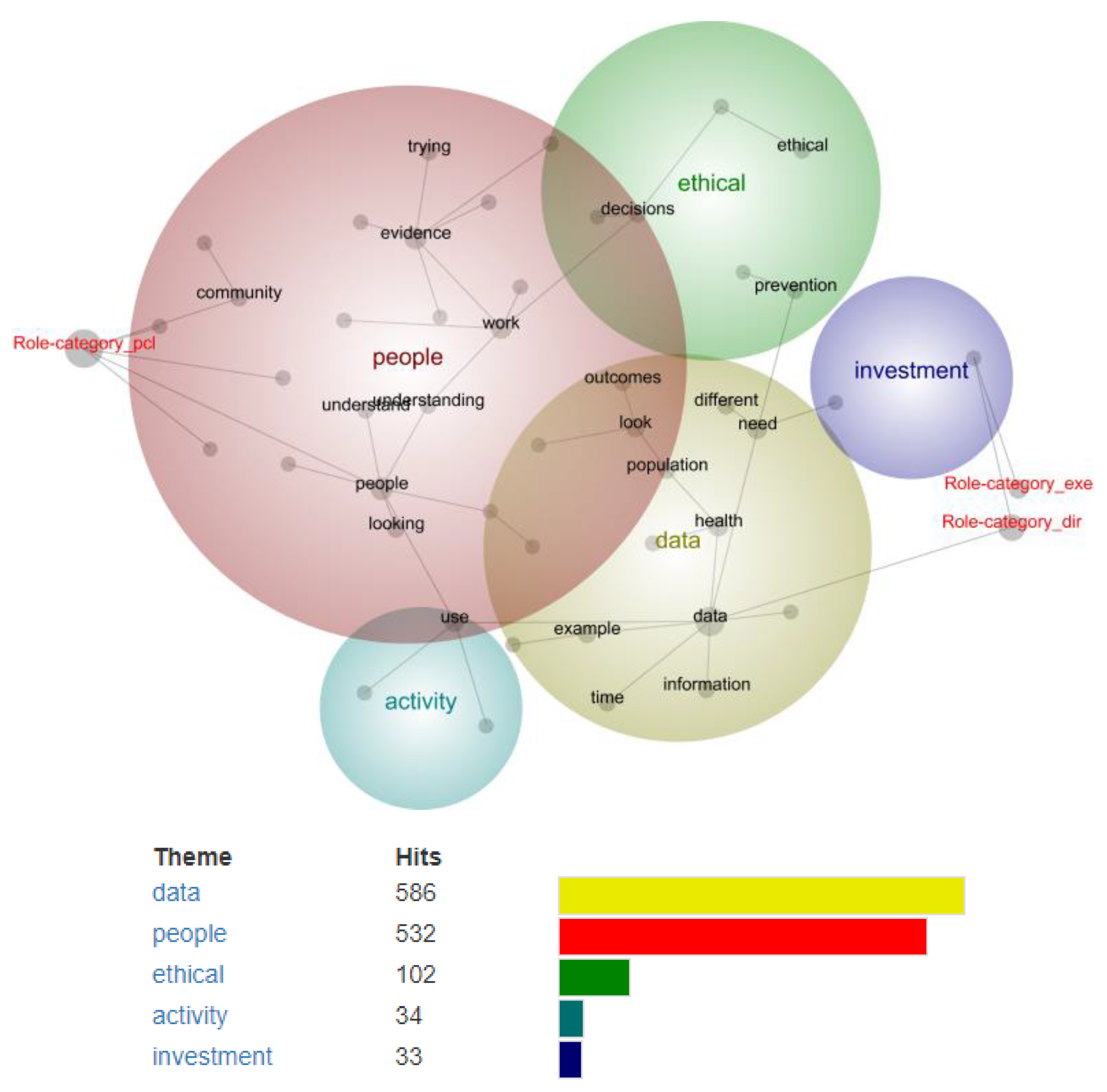

3.2. Stage One—Identifying Preliminary Themes and Concepts Using Leximancer

3.3. Stage Two—Final Themes and Sub-Themes of Preventive Decision-Making in Healthcare Organisations

3.3.1. Theme 1—Data

3.3.2. Theme 2—Evidence

3.3.3. Minor Theme—Evidence-Ethical

3.3.4. Theme 3—Ethics

3.3.5. Theme 4—Health

3.3.6. Participant Feedback

- Other decision-making settings in healthcare (e.g., point-of-care)

- An investment model for prevention (and an evidence-based mechanism to increase investment)

- A decision-making tool that can help guide investment (or disinvestment) at an organisational level, and not just a tool that describes how decisions are made.

3.4. Subgroup Analysis

3.4.1. Organisation

3.4.2. Role Category

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Comparison to Literature

4.3. Implications for Practice

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheet—Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Bray, G.A.; Kim, K.K.; Wilding, J.P.H. Obesity: A chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and Causes of Illness and Death in Australia 2018; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2021.

- Commonwealth of Australia. The National Obesity Strategy 2022–2032; Department of Health and Aged Care, Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2022.

- Canfell, O.J.; Davidson, K.; Sullivan, C.; Eakin, E.; Burton-Jones, A. Data sources for precision public health of obesity: A scoping review, evidence map and use case in Queensland, Australia. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canfell, O.J.; Littlewood, R.; Burton-Jones, A.; Sullivan, C. Digital health and precision prevention: Shifting from disease-centred care to consumer-centred health. Aust. Health Rev. 2021, 46, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odone, A.; Buttigieg, S.; Ricciardi, W.; Azzopardi-Muscat, N.; Staines, A. Public health digitalization in Europe: EUPHA vision, action and role in digital public health. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29 (Suppl. 3), 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, B.L.H.; Maaß, L.; Vodden, A.; van Kessel, R.; Sorbello, S.; Buttigieg, S.; Odone, A. The dawn of digital public health in Europe: Implications for public health policy and practice. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022, 14, 100316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfell, O.J.; Davidson, K.; Woods, L.; Sullivan, C.; Cocoros, N.M.; Klompas, M.; Zambarano, B.; Eakin, E.; Littlewood, R.; Burton-Jones, A. Precision Public Health for Non-communicable Diseases: An Emerging Strategic Roadmap and Multinational Use Cases. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, C.; Wong, I.; Adams, E.; Fahim, M.; Fraser, J.; Ranatunga, G.; Busato, M.; McNeil, K. Moving Faster than the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Rapid, Digital Transformation of a Public Health System. Appl. Clin. Inf. 2021, 12, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, J.; Miller, B.S.; Manning, E.M.; Lampos, V.; Zhuang, M.; Edelstein, M.; Rees, G.; Emery, V.C.; Stevens, M.M.; Keegan, N.; et al. Digital technologies in the public-health response to COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Alamro, N.M.S.; Hwang, H.; Lee, U. Digital public health and COVID-19. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e469–e470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannahill, A. Beyond evidence—To ethics: A decision-making framework for health promotion, public health and health improvement. Health Promot. Int. 2008, 23, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J. Designing a Qualitative Study. In The SAGE Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009; Available online: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/the-sage-handbook-of-applied-social-research-methods-2e (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Thorpe, S.; Young, T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leximancer Pty Ltd. Leximancer User Guide: Release 4.5; Leximancer Pty Ltd.: Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, E.; Green, J.; Garside, R.; Kelly, M.P.; Guell, C. Gender and active travel: A qualitative data synthesis informed by machine learning. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, E.; Garside, R.; Green, J.; Kelly, M.P.; Thomas, J.; Guell, C. Semiautomated text analytics for qualitative data synthesis. Res. Synth. Methods 2019, 10, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenicek, M. Epidemiology, evidenced-based medicine, and evidence-based public health. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 7, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownson, R.C.; Gurney, J.G.; Land, G.H. Evidence-based decision making in public health. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 1999, 5, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohatsu, N.D.; Robinson, J.G.; Torner, J.C. Evidence-based public health: An evolving concept. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 27, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nundy, S.; Cooper, L.A.; Mate, K.S. The Quintuple Aim for Health Care Improvement: A New Imperative to Advance Health Equity. JAMA 2022, 327, 521–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S.M.; Rychetnik, L.; Lloyd, B.; Kerridge, I.H.; Baur, L.; Bauman, A.; Hooker, C.; Zask, A. Evidence, Ethics, and Values: A Framework for Health Promotion. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, L.; Morgan, A.; Fischer, A.; Ellis, S.; Hoy, A.; Kelly, M.P. The cost-effectiveness of public health interventions. J. Public Health 2012, 34, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolley, S. Big data’s role in precision public health. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattison, G.; Canfell, O.; Forrester, D.; Dobbins, C.; Smith, D.; Töyräs, J.; Sullivan, C. The Influence of Wearables on Health Care Outcomes in Chronic Disease: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e36690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, S.L.; Aung, M.T.; Chartres, N.; Woodruff, T.J. Evidence-to-decision frameworks: A review and analysis to inform decision-making for environmental health interventions. Environ. Health 2021, 20, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberg, J.; Oxman, A.D.; Rosenbaum, S.; Schünemann, H.J.; Guyatt, G.; Flottorp, S.; Glenton, C.; Lewin, S.; Morelli, A.; Rada, G.; et al. The GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework for health system and public health decisions. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesen, V.M.; Mbuya, M.N.N.; Wieringa, F.T.; Nelson, C.N.; Ojo, M.; Neufeld, L.M. Decisions to Start, Strengthen, and Sustain Food Fortification Programs: An Application of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Evidence to Decision (EtD) Framework in Nigeria. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022, 6, nzac010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, P.A.; Reich, M.R. Political Analysis for Health Policy Implementation. Health Syst. Reform. 2019, 5, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Babad, Y.M. Balancing influence between actors in healthcare decision making. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain | Questions | Prompts |

|---|---|---|

| “In the context of this study, preventive decision-making refers to any organisational decision that targets disease prevention at all levels of healthcare and public health.” Decisions may use a combination of ethics, evidence and theory. | ||

| Ethics | What is your understanding of ethical decision-making? | For prevention? In the context of your organisation? |

| How do you practice ethical decision-making in your current role? | What is an example? | |

| Evidence | How does evidence influence your decision-making? | As a team? As an organisation? |

| How do you currently use data to inform decision-making? | ||

| Ideally, what data do you need to make the best decisions? | ||

| How would you define an evidence-based decision for prevention? | What is an example? | |

| What is an example of a preventive evidence-based decision you have made in your current role? | What data did you use? | |

| Theory (i.e., experiential, and professional judgment) | What is your attitude towards using theory for preventive decision-making? | |

| When do your decisions draw upon theory? | ||

| What is an example of a preventive theory-based decision you have made in your current role? | ||

| Demographic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Role category | |

| Executive | 2 (14) |

| Director/Manager | 5 (36) |

| Project/Clinical Lead | 7 (50) |

| Professional background | |

| Clinical | 4 (29) |

| Public Health | 5 (36) |

| Information Technology | 2 (14) |

| Research | 1 (7) |

| Project | 1 (7) |

| Operational | 1 (7) |

| Time in current role | |

| 0–6 months | 0 (0) |

| 6–12 months | 2 (14) |

| 1–2 years | 6 (42) |

| 2–5 years | 3 (22) |

| >5 years | 3 (22) |

| Years of experience | |

| 0–2 years | 1 (7) |

| 2–5 years | 1 (7) |

| 6–10 years | 2 (14) |

| 11–20 years | 6 (43) |

| 21–30 years | 4 (29) |

| >30 years | 0 (0) |

| Theme | Sub-Theme | |

|---|---|---|

| 1—Data | 1A | Data is a tool to generate trust in decision-making |

| 1B | Data storytelling is used to demonstrate the value of prevention | |

| 1C | Better data access and quality is needed to improve the precision of decision-making | |

| 1D | The data paradox: change-agents want more data, but data usability is inversely proportional to data amount | |

| 2—Evidence | 2A | Traditional evidence is critical to decision-making but is only one piece of a larger evidential puzzle |

| 2B | Non-traditional sources of evidence (e.g., innovation, experience) are strongly weighted in prevention | |

| Evidence-Ethical (Minor) | EE | The strength of all evidence (traditional and non-traditional) is directly proportional to the ethical rigor of a decision |

| 3—Ethics | 3A | Decisions carry a weight of responsibility to the taxpayer, community, and organisation |

| 3B | Decisions must ultimately be fair and contextualised for equity—to target those with the greatest health need | |

| 4—Health | 4A | “Health” decisions are driven by everything outside of health |

| 4B | Healthcare and disease prevention ultimately relates back to dollars |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Canfell, O.J.; Davidson, K.; Sullivan, C.; Eakin, E.E.; Burton-Jones, A. PREVIDE: A Qualitative Study to Develop a Decision-Making Framework (PREVention decIDE) for Noncommunicable Disease Prevention in Healthcare Organisations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215285

Canfell OJ, Davidson K, Sullivan C, Eakin EE, Burton-Jones A. PREVIDE: A Qualitative Study to Develop a Decision-Making Framework (PREVention decIDE) for Noncommunicable Disease Prevention in Healthcare Organisations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):15285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215285

Chicago/Turabian StyleCanfell, Oliver J., Kamila Davidson, Clair Sullivan, Elizabeth E. Eakin, and Andrew Burton-Jones. 2022. "PREVIDE: A Qualitative Study to Develop a Decision-Making Framework (PREVention decIDE) for Noncommunicable Disease Prevention in Healthcare Organisations" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 15285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215285

APA StyleCanfell, O. J., Davidson, K., Sullivan, C., Eakin, E. E., & Burton-Jones, A. (2022). PREVIDE: A Qualitative Study to Develop a Decision-Making Framework (PREVention decIDE) for Noncommunicable Disease Prevention in Healthcare Organisations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215285