ASPHALT II: Study Protocol for a Multi-Method Evaluation of a Comprehensive Peer-Led Youth Community Sport Programme Implemented in Low Resource Neighbourhoods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Aims

2.2. Context

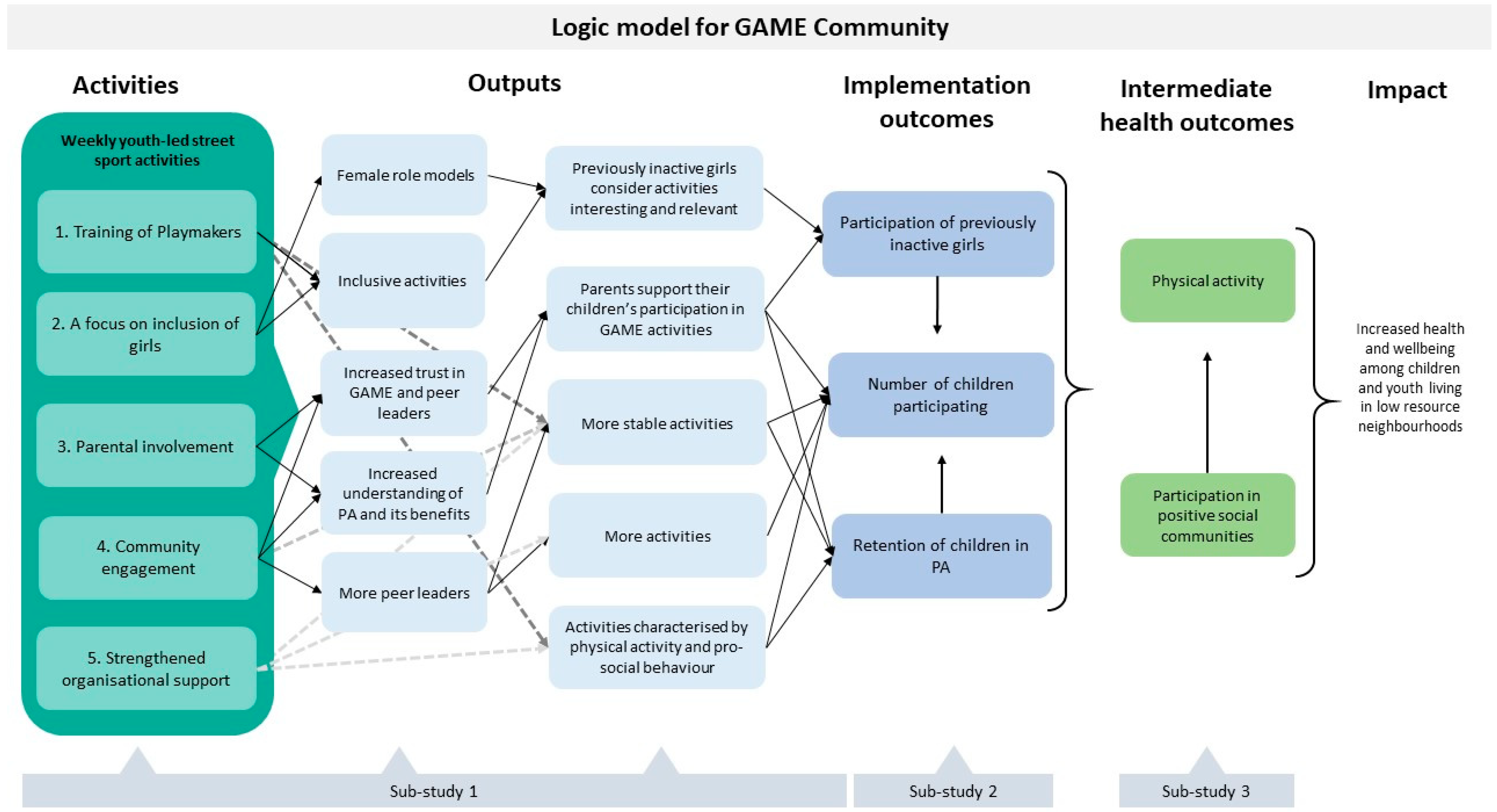

2.3. The GAME Community Intervention

2.3.1. Training of Playmakers

2.3.2. Inclusion of Inactive Girls

2.3.3. Parental Involvement

2.3.4. Community Engagement

2.3.5. Organisational Support

3. Evaluation Design and Methodology

3.1. Sub-Study 1: Functioning of the GAME Community Programme

3.2. Sub-Study 2: Reach and Retention of Participants

3.3. Sub-Study 3: The Health Enhancing Potential of GAME Community

4. Discussion

4.1. Importance of This Study

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Janssen, I.; LeBlanc, A.G. Systematic Review of the Health Benefits of Physical Activity and Fitness in School-Aged Children and Youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, L.B.; Hasselstrøm, H.; Grønfeldt, V.; Hansen, S.E.; Karsten, F. The Relationship between Physical Fitness and Clustered Risk, and Tracking of Clustered Risk from Adolescence to Young Adulthood: Eight Years Follow-up in the Danish Youth and Sport Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2004, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Telama, R. Tracking of Physical Activity from Childhood to Adulthood: A Review. Obes. Facts 2009, 2, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global Trends in Insufficient Physical Activity among Adolescents: A Pooled Analysis of 298 Population-Based Surveys with 1.6 Million Participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sluijs, E.M.F.; Ekelund, U.; Crochemore-Silva, I.; Guthold, R.; Ha, A.; Lubans, D.; Oyeyemi, A.L.; Ding, D.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Physical Activity Behaviours in Adolescence: Current Evidence and Opportunities for Intervention. Lancet 2021, 398, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W.C.; Baranowski, T.; Young, D.R. Physical Activity Interventions in Low-Income, Ethnic Minority, and Populations with Disability. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 15, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cervero, R.B.; Ascher, W.; Henderson, K.A.; Kraft, M.K.; Kerr, J. An Ecological Approach to Creating Active Living Communites. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2006, 27, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.M.; Thompson, A.M.; Blair, S.N.; Sallis, J.F.; Powell, K.E.; Bull, F.C.; Bauman, A.E. Sport and Exercise as Contributors to the Health of Nations. Lancet 2012, 380, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, G.; Grønfeldt, V.; Toftegaard-Støckel, J.; Andersen, L.B. Predisposed to Participate? The Influence of Family Socio-Economic Background on Children’s Sports Participation and Daily Amount of Physical Activity. Sport Soc. 2012, 15, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, G.; Hermansen, B.; Bugge, A.; Dencker, M.; Andersen, L.B. Daily Physical Activity and Sports Participation among Children from Ethnic Minorities in Denmark. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2013, 13, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, K.B.; Nau, T.; Reece, L.J.; Bellew, W.; Rose, C.; Bauman, A.; Halim, N.K.; Smith, B.J. Fair Play? Participation Equity in Organised Sport and Physical Activity among Children and Adolescents in High Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandbu, Å.; Bakken, A.; Sletten, M.A. Exploring the Minority–Majority Gap in Sport Participation: Different Patterns for Boys and Girls? Sport Soc. 2019, 22, 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehsenfeld, M.; Mindegaard, P.; Ibsen, B. Your GAM3: Gadeidræt I Udsatte Boligområder. Movements; 1. Oplag; Center for Forskning i Idræt, Sundhed og Civilsamfund: Odense, Denmark, 2013; ISBN 978-87-92646-67-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chzhen, Y.; Moor, I.; Pickett, W.; Toczydlowska, E.; Stevens, G.W.J.M. International Trends in ‘Bottom-End’ Inequality in Adolescent Physical Activity and Nutrition: HBSC Study 2002–2014. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corr, M.; McSharry, J.; Murtagh, E.M. Adolescent Girls’ Perceptions of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Am. J. Health Promot. 2019, 33, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttmacher, S.; Kelly, P.J.; Ruiz-Janecko, Y. Community-Based Health Interventions: Principles and Applications, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-470-57500-0. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, N.B.; Duran, B. Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Address Health Disparities. Health Promot. Pract. 2006, 7, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, R.R.; Trost, S.G.; Mullis, R.; Sallis, J.F.; Wechsler, H.; Brown, D.R. Community Interventions to Promote Proper Nutrition and Physical Activity among Youth. Prev. Med. 2000, 31, S138–S149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Santelli, J.S.; Ross, D.A.; Afifi, R.; Allen, N.B.; Arora, M.; Azzopardi, P.; Baldwin, W.; Bonell, C.; et al. Our Future: A Lancet Commission on Adolescent Health and Wellbeing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald-Wallis, K.; Jago, R.; Sterne, J.A.C. Social Network Analysis of Childhood and Youth Physical Activity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, S.C.; Donnelly, M.; Bhatnagar, P.; Carlin, A.; Kee, F.; Hunter, R.F. Peer Social Network Processes and Adolescent Health Behaviors: A Systematic Review. Prev. Med. 2020, 130, 105900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, F.; Simbar, M. The Peer Education Approach in Adolescents—Narrative Review Article. Iran. J. Public Health 2013, 42, 1200–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Simoni, J.M.; Franks, J.C.; Lehavot, K.; Yard, S.S. Peer Interventions to Promote Health: Conceptual Considerations. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2011, 81, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, G.; Shepherd, J. A Method in Search of a Theory: Peer Education and Health Promotion. Health Educ. Res. 1999, 14, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.H.; Elsborg, P.; Melby, P.S.; Nielsen, G.; Bentsen, P. A Scoping Review of Peer-Led Physical Activity Interventions Involving Young People: Theoretical Approaches, Intervention Rationales, and Effects. Youth Soc. 2021, 53, 811–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, F.; Ng, K.; Taylor, S.; Bengoechea, E.; Norton, C.; O’Shea, D.; Woods, C. A Systematic Literature Review of Peer-Led Strategies for Promoting Physical Activity Levels of Adolescents. Health Educ. Behav. 2021, 49, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GAME Web 1. Where We Work. Available online: https://game.ngo/where-we-work/ (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- GAME Web 2. Available online: https://game.ngo/ (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Danish Housing and Planning Authority. Udsatte Områder og Parallelsamfund. Available online: https://bpst.dk/da/Bolig/Udsatte-boligomraader/Udsatte-omraader-og-parallelsamfund (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Prahm, S. Mere Fællesskab End Forening. Available online: https://simonprahm.wordpress.com/2016/05/24/mere-faellesskab-end-forening/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Indig, D.; Lee, K.; Grunseit, A.; Milat, A.; Bauman, A. Pathways for Scaling up Public Health Interventions. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landes, S.J.; McBain, S.A.; Curran, G.M. Reprint of: An Introduction to Effectiveness-Implementation Hybrid Designs. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 283, 112630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rod, M.H.; Ingholt, L.; Bang Sørensen, B.; Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T. The spirit of the intervention: Reflections on social effectiveness in public health intervention research. Crit. Public Health 2014, 24, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonell, C.; Jamal, F.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Cummins, S. ‘Dark Logic’: Theorising the Harmful Consequences of Public Health Interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 69, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawe, P. Lessons from Complex Interventions to Improve Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogilvie, D.; Bauman, A.; Foley, L.; Guell, C.; Humphreys, D.; Panter, J. Making Sense of the Evidence in Population Health Intervention Research: Building a Dry Stone Wall. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e004017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A New Framework for Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: Update of Medical Research Council Guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, H.; Naylor, P.-J.; Lau, E.; Gray, S.M.; Wolfenden, L.; Milat, A.; Bauman, A.; Race, D.; Nettlefold, L.; Sims-Gould, J. Implementation and Scale-up of Physical Activity and Behavioural Nutrition Interventions: An Evaluation Roadmap. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawe, P.; Shiell, A.; Riley, T. Complex Interventions: How “Out of Control” Can a Randomised Controlled Trial Be? BMJ 2004, 328, 1561–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, T.L.; Sallis, J.F.; Nader, P.R. SOFIT: System for Observing Fitness Instruction Time. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 1991, 11, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgers, N.D.; Stratton, G.; McKenzie, T.L. Reliability and Validity of the System for Observing Children’s Activity and Relationships during Play (SOCARP). J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, T.L. SOFIT (System for Observing Fitness Instruction Time). Description and Procedures Manual 2015; School of Exercise and Nutritional Sciences, San Diego State University: San Diego, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgers, N.D.; McKenzie, T.L.; Stratton, G. System for Observing Children’s Activity and Relationships during Play (SOCARP). Description and Procedures Manual; Ridgers, N.D., McKenzie, T.L., Stratton, G., Eds.; Centre for Physical Activity and Nutrition Research, Deakin University: Geelong, VI, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam, D. Health Literacy as a Public Health Goal: A Challenge for Contemporary Health Education and Communication Strategies into the 21st Century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: The New Medical Research Council Guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, a1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gann, D.; Salter, A. Interdisciplinary Skills for Built Environment Professionals. A Scoping Study; The Arup Foundation: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Castonguay, L.G.; Youn, S.J.; Xiao, H.; Muran, J.C.; Barber, J.P. Building Clinicians-Researchers Partnerships: Lessons from Diverse Natural Settings and Practice-Oriented Initiatives. Psychother. Res. 2014, 25, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Haines, A.; Kinmonth, A.L.; Sandercock, P.; Spiegelhalter, D.; Tyrer, P. Framework for Design and Evaluation of Complex Interventions to Improve Health. BMJ 2000, 321, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, J.S.; Anderson, J.; Hunter, R.F.; French, D.P. The Effect of Changing the Built Environment on Physical Activity: A Quantitative Review of the Risk of Bias in Natural Experiments. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics. Available online: https://www.nvk.dk/ (accessed on 8 September 2022).

| Sub-Study | Research Question | Design and Methods | Population | Data | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Functioning of the intervention (activities and outputs) | What is the functioning of the GAME Community programme? | Qualitative interviews and focus groups | Playmakers, parents, community stakeholders from 6 GAME Zones with varying implementation scores | Participants’ perceptions of the implementation and impact of the five GAME community components | 2023 |

| 2. Reach and retention of participants (implementation outcomes) | What is the relationship between degree of implementation and implementation outcomes? | Structured interviews with regional GAME officers and longitudinal participant registration | All GAME Zones | Each of the five GAME community components will be assigned a score from 1 (not implemented) to 5 (fully implemented) and combined with app data | Time 1: 2021, Time 2: 2022, Time 3: 2023 |

What are the relations between implementation of the GAME Community components and programme reach and retention? | Qualitative interviews, focus groups and longitudinal participant registration | Playmakers, parents, community stakeholders from 6 GAME Zones with varying implementation scores | Participants’ perceptions of the implementation combined with participant registrations (app) on: gender, age, participation in other leisure activities, number of GAME activities attended | 2022–2023 | |

Which components of the programme contribute to engage and retain girls in GAME activities? | Ethnographic field study | Girls who are active in GAME Zones with a high degree of girl participation | Participating girls’ experiences of participating in GAME activities, social interactions and interaction with peer leaders | 2023 | |

| 3. The health enhancing potential of GAME Community (intermediate health outcomes) | What is the health enhancing potential of participation in GAME Community? E.g., retention in activities characterised by physical activity and pro-social behaviour? | Systematic observations of each activity at four time points using a combination of SOFIT and SOCARP. Longitudinal participant registration | All children attending GAME activities that are conducted in public open space and with a mean attendance of >5 children | (a) PA level among participating children, (b) participants’ social behaviour and interactions, (c) activity content and (d) features of the physical context will be assessed and combined with app data. | 2022–2023 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Christensen, J.H.; Ljungmann, C.K.; Pawlowski, C.S.; Johnsen, H.R.; Olsen, N.; Hulgård, M.; Bauman, A.; Klinker, C.D. ASPHALT II: Study Protocol for a Multi-Method Evaluation of a Comprehensive Peer-Led Youth Community Sport Programme Implemented in Low Resource Neighbourhoods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215271

Christensen JH, Ljungmann CK, Pawlowski CS, Johnsen HR, Olsen N, Hulgård M, Bauman A, Klinker CD. ASPHALT II: Study Protocol for a Multi-Method Evaluation of a Comprehensive Peer-Led Youth Community Sport Programme Implemented in Low Resource Neighbourhoods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):15271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215271

Chicago/Turabian StyleChristensen, Julie Hellesøe, Cecilie Karen Ljungmann, Charlotte Skau Pawlowski, Helene Rald Johnsen, Nikoline Olsen, Mathilde Hulgård, Adrian Bauman, and Charlotte Demant Klinker. 2022. "ASPHALT II: Study Protocol for a Multi-Method Evaluation of a Comprehensive Peer-Led Youth Community Sport Programme Implemented in Low Resource Neighbourhoods" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 15271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215271

APA StyleChristensen, J. H., Ljungmann, C. K., Pawlowski, C. S., Johnsen, H. R., Olsen, N., Hulgård, M., Bauman, A., & Klinker, C. D. (2022). ASPHALT II: Study Protocol for a Multi-Method Evaluation of a Comprehensive Peer-Led Youth Community Sport Programme Implemented in Low Resource Neighbourhoods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215271