Effects of Vaping Prevention Messages on Electronic Vapor Product Beliefs, Perceived Harms, and Behavioral Intentions among Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

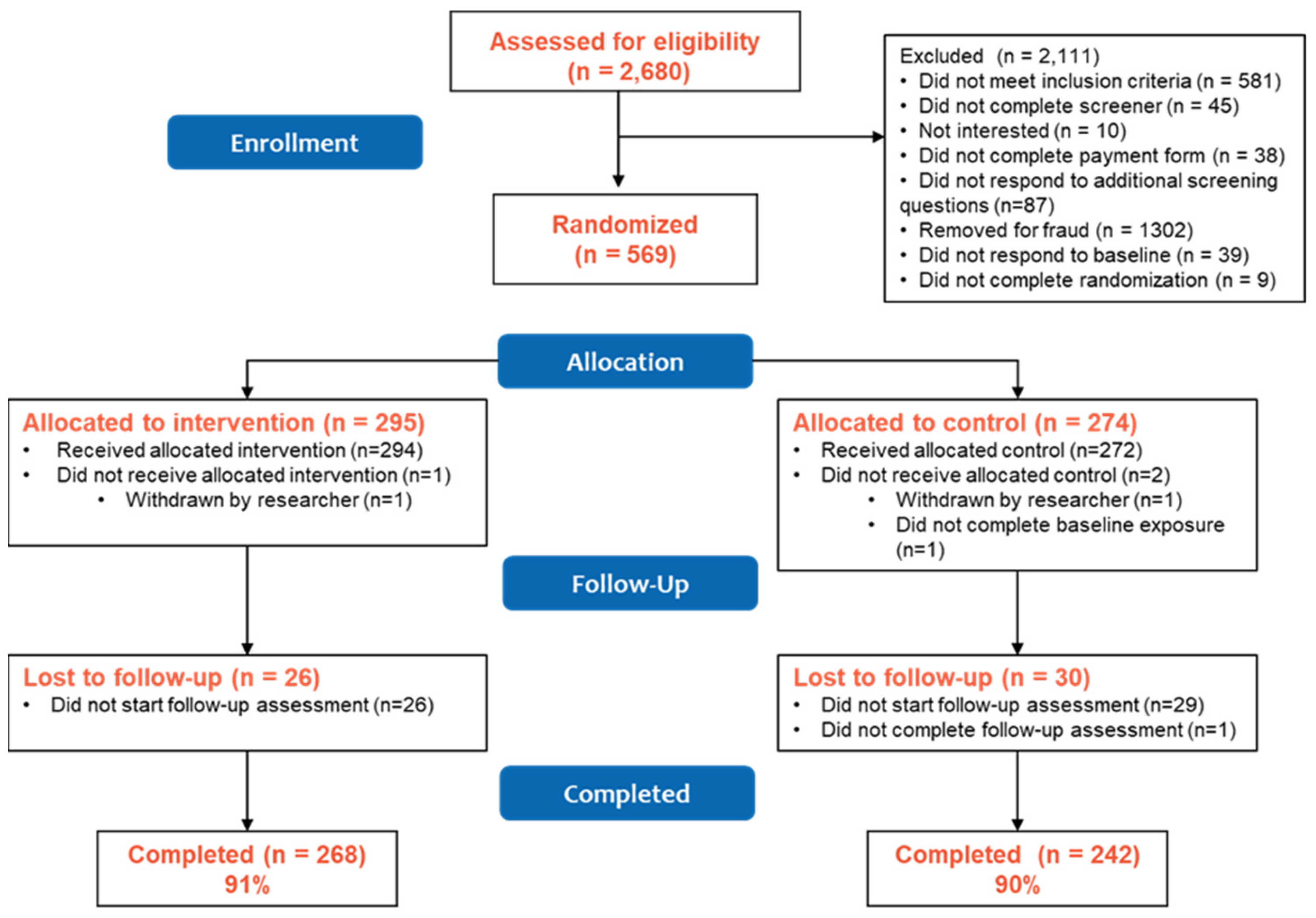

2.1. Trial Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Study Conditions

2.3.1. Intervention Condition

2.3.2. Control Condition

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Baseline Characteristics

2.4.2. Tobacco Use

2.4.3. Response to Study Messages

2.4.4. Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Study Condition on Message Responses

3.2. Effect of Study Condition on Primary Outcomes: Vaping-Related Beliefs and Harm Perceptions

3.3. Effect of Study Condition on Secondary Outcomes: Vaping-Related Norms, Behavioral Intentions and Behaviors

3.4. Effect of Study Condition on Potential Spillover Effects

3.5. Exploratory Analyses of the Role of Message Engagement on Study Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, X.; Alexander, T.N.; Hoffman, L.; Jones, C.; Delahanty, J.; Walker, M.; Berger, A.T.; Talbert, E. Youth Receptivity to FDA’s The Real Cost Tobacco Prevention Campaign: Evidence From Message Pretesting. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kranzler, E.C.; Gibson, L.A.; Hornik, R.C. Recall of “The Real Cost” Anti-Smoking Campaign Is Specifically Associated With Endorsement of Campaign-Targeted Beliefs. J. Health Commun. 2017, 22, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershey, J.C.; Niederdeppe, J.; Evans, W.D.; Nonnemaker, J.; Blahut, S.; Holden, D.; Messeri, P.; Haviland, M.L. The theory of “truth”: How counterindustry campaigns affect smoking behavior among teens. Health Psychol. 2005, 24, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrelly, M.C.; Davis, K.C.; Duke, J.; Messeri, P. Sustaining ‘truth’: Changes in youth tobacco attitudes and smoking intentions after 3 years of a national antismoking campaign. Health Educ. Res. 2009, 24, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs—2014; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014.

- Duke, J.C.; Farrelly, M.C.; Alexander, T.N.; MacMonegle, A.J.; Zhao, X.; Allen, J.A.; Delahanty, J.C.; Rao, P.; Nonnemaker, J. Effect of a National Tobacco Public Education Campaign on Youth’s Risk Perceptions and Beliefs About Smoking. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 1248–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, J.C.; MacMonegle, A.J.; Nonnemaker, J.M.; Farrelly, M.C.; Delahanty, J.C.; Zhao, X.; Smith, A.A.; Rao, P.; Allen, J.A. Impact of The Real Cost Media Campaign on Youth Smoking Initiation. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, M.C.; Duke, J.C.; Nonnemaker, J.; MacMonegle, A.J.; Alexander, T.N.; Zhao, X.; Delahanty, J.C.; Rao, P.; Allen, J.A. Association Between The Real Cost Media Campaign and Smoking Initiation Among Youths-United States, 2014–2016. Mmwr. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2017, 66, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Real Cost: Don’t Get Hacked by Vaping. Available online: https://therealcost.betobaccofree.hhs.gov/gm/hacked-ends.html (accessed on 6 April 2019).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The Real Cost E-Cigarette Prevention Campaign 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/real-cost-campaign/real-cost-e-cigarette-prevention-campaign (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Vereen, R.N.; Krajewski, T.J.; Wu, E.Y.; Zhang, J.H.; Sanzo, N.; Noar, S.M. Aided recall of The Real Cost e-cigarette prevention advertisements among a nationally representative sample of adolescents. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 28, 101864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMonegle, A.J.; Smith, A.A.; Duke, J.; Bennett, M.; Siegel-Reamer, L.R.; Pitzer, L.; Speer, J.L.; Zhao, X. Effects of a National Campaign on Youth Beliefs and Perceptions About Electronic Cigarettes and Smoking. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2022, 19, E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truth Initiative. truth 2022. Available online: https://www.thetruth.com/ (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- American Lung Association. Talk About Vaping. 2022. Available online: https://www.lung.org/quit-smoking/helping-teens-quit/talk-about-vaping (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- King, B.A.; Patel, R.; Nguyen, K.H.; Dube, S.R. Trends in awareness and use of electronic cigarettes among US adults, 2010-2013. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015, 17, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillen, R.C.; Gottlieb, M.A.; Shaefer, R.M.; Winickoff, J.P.; Klein, J.D. Trends in Electronic Cigarette Use Among, U.S. Adults: Use is Increasing in Both Smokers and Nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015, 17, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delnevo, C.D.; Giovenco, D.P.; Steinberg, M.B.; Villanti, A.C.; Pearson, J.L.; Niaura, R.S.; Abrams, D.B. Patterns of Electronic Cigarette Use Among Adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016, 18, 715–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasza, K.A.; Ambrose, B.K.; Conway, K.P.; Borek, N.; Taylor, K.; Goniewicz, M.L.; Cummings, K.M.; Sharma, E.; Pearson, J.L.; Green, V.R.; et al. Tobacco-Product Use by Adults and Youths in the United States in 2013 and 2014. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, H.; Leventhal, A.M. Prevalence of e-Cigarette Use Among Adults in the United States, 2014–2018. JAMA 2019, 322, 1824–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallone, D.M.; Bennett, M.; Xiao, H.; Pitzer, L.; Hair, E.C. Prevalence and correlates of JUUL use among a national sample of youth and young adults. Tob. Control. 2018, 28, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKelvey, K.; Baiocchi, M.; Halpern-Felsher, B. Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Use and Perceptions of Pod-Based Electronic Cigarettes. JAMA Netw. Open. 2018, 1, e183535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leavens, E.L.S.; Stevens, E.M.; Brett, E.I.; Hebert, E.T.; Villanti, A.C.; Pearson, J.L.; Wagener, T.L. JUUL electronic cigarette use patterns, other tobacco product use, and reasons for use among ever users: Results from a convenience sample. Addict. Behav. 2019, 95, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ickes, M.; Hester, J.W.; Wiggins, A.T.; Rayens, M.K.; Hahn, E.J.; Kavuluru, R. Prevalence and reasons for Juul use among college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2019, 68, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, D.; Wackowski, O.A.; Reid, J.L.; O’Connor, R.J. Use of Juul E-Cigarettes Among Youth in the United States. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2018, 22, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, D.T.; Zavala-Arciniega, L.; Hirschtick, J.L.; Meza, R.; Levy, D.T.; Fleischer, N.L. Trends in Exclusive, Dual and Polytobacco Use among U.S. Adults, 2014-2019: Results from Two Nationally Representative Surveys. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, K.A.; Ambrose, B.K.; Gentzke, A.S.; Apelberg, B.J.; Jamal, A.; King, B.A. Notes from the Field: Use of Electronic Cigarettes and Any Tobacco Product Among Middle and High School Students-United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2018, 67, 1276–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, J.M.; Romberg, A.R.; Perks, S.N.; Edwards, D.; Vallone, D.M.; Hair, E.C. Identifying message themes to prevent e-cigarette use among youth and young adults. Prev. Med. 2021, 150, 106683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.C.; Mays, D.; Netemeyer, R.G.; Burton, S.; Kees, J. Effects of E-Cigarette Health Warnings and Modified Risk Ad Claims on Adolescent E-Cigarette Craving and Susceptibility. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 21, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabro, K.S.; Khalil, G.E.; Chen, M.; Perry, C.L.; Prokhorov, A.V. Pilot study to inform young adults about the risks of electronic cigarettes through text messaging. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2019, 10, 100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazard, A.J. Social Media Message Designs to Educate Adolescents About E-Cigarettes. J. Adolesc Health 2021, 68, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.S.L.; Rees, V.W.; Rodgers, J.; Agudile, E.; Sokol, N.A.; Yie, K.; Sanders-Jackson, A. Effects of exposure to anti-vaping public service announcements among current smokers and dual users of cigarettes and electronic nicotine delivery systems. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 188, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, K.J.; Edwards, A.L.; Paulson, A.C.; Libby, E.P.; Harrell, P.T.; Mondejar, K.A. Rethink Vape: Development and evaluation of a risk communication campaign to prevent youth E-cigarette use. Addict. Behav. 2020, 113, 106664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noar, S.M.; Rohde, J.A.; Prentice-Dunn, H.; Kresovich, A.; Hall, M.G.; Brewer, N.T. Evaluating the actual and perceived effectiveness of E-cigarette prevention advertisements among adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2020, 109, 106473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, T.J.; Ellen, P.S.; Ajzen, I. A Comparison of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, C.J.; Stratton, E.; Schauer, G.L.; Lewis, M.; Wang, Y.; Windle, M.; Kegler, M. Perceived harm, addictiveness, and social acceptability of tobacco products and marijuana among young adults: Marijuana, hookah, and electronic cigarettes win. Subst. Use Misuse 2015, 50, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wackowski, O.A.; Delnevo, C.D. Young Adults’ Risk Perceptions of Various Tobacco Products Relative to Cigarettes: Results From the National Young Adult Health Survey. Health Educ. Behav. 2016, 43, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elton-Marshall, T.; Driezen, P.; Fong, G.T.; Cummings, K.M.; Persoskie, A.; Wackowski, O.; Choi, K.; Kaufman, A.; Strong, D.; Gravely, S.; et al. Adult perceptions of the relative harm of tobacco products and subsequent tobacco product use: Longitudinal findings from waves 1 and 2 of the population assessment of tobacco and health (PATH) study. Addict. Behav. 2020, 106, 106337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallo, D.A.; Kong, G.; Ells, D.M.; Camenga, D.R.; Morean, M.E.; Krishnan-Sarin, S. Youth generated prevention messages about electronic cigarettes. Health Educ. Res. 2019, 34, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escoto, A.; Watkins, S.L.; Welter, T.; Beecher, S. Developing a targeted e-cigarette health communication campaign for college students. Addict. Behav. 2021, 117, 106841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanti, A.C.; Johnson, A.L.; Ambrose, B.K.; Cummings, K.M.; Stanton, C.A.; Rose, S.W.; Feirman, S.P.; Tworek, C.; Glasser, A.M.; Pearson, J.L.; et al. Flavored Tobacco Product Use in Youth and Adults: Findings From the First Wave of the PATH Study (2013–2014). Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanti, A.C.; LePine, S.E.; West, J.C.; Cruz, T.B.; Stevens, E.M.; Tetreault, H.J.; Unger, J.B.; Wackowski, O.A.; Mays, D. Identifying message content to reduce vaping: Results from online message testing trials in young adult tobacco users. Addict. Behav. 2021, 115, 106778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanti, A.C.; West, J.C.; Mays, D.; Donny, E.C.; Cappella, J.N.; Strasser, A.A. Impact of Brief Nicotine Messaging on Nicotine-Related Beliefs in a U.S. Sample. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, e135–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, D.; Johnson, A.C.; Phan, L.; Tercyak, K.P.; Rehberg, K.; Lipkus, I. Effect of risk messages on risk appraisals, attitudes, ambivalence, and willingness to smoke hookah in young adults. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2020, 8, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, L.; Villanti, A.C.; Leshner, G.; Wagener, T.L.; Stevens, E.M.; Johnson, A.C. Development and Pretesting of Hookah Tobacco Public Education Messages for Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanti, A.C.; Vallencourt, C.P.; West, J.C.; Peasley-Miklus, C.; LePine, S.E.; McCluskey, C.; Klemperer, E.; Priest, J.S.; Logan, A.; Patton, B.; et al. Recruiting and Retaining Youth and Young Adults in the Policy and Communication Evaluation (PACE) Vermont Study: Randomized Controlled Trial of Participant Compensation. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LePine, S.E.; Peasley-Miklus, C.; Farrington, M.L.; Young, W.J.; Bover Manderski, M.T.; Hrywna, M.; Villanti, A.C. Ongoing refinement and adaptation are required to address participant deception in online nicotine and tobacco research studies. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, V.F.; Smith, A.A.; Villanti, A.C.; Rath, J.M.; Hair, E.C.; Cantrell, J.; Teplitskaya, L.; Vallone, D.M. Validity of a Subjective Financial Situation Measure to Assess Socioeconomic Status in US Young Adults. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2017, 23, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanti, A.C.; Gaalema, D.E.; Tidey, J.W.; Kurti, A.N.; Sigmon, S.C.; Higgins, S.T. Co-occurring vulnerabilities and menthol use in U.S. young adult cigarette smokers: Findings from Wave 1 of the PATH Study, 2013–2014. Prev. Med. 2018, 117, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delahanty, J.; Ganz, O.; Hoffman, L.; Guillory, J.; Crankshaw, E.; Farrelly, M. Tobacco use among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender young adults varies by sexual and gender identity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 201, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanti, A.C.; Johnson, A.L.; Rath, J.M. Beyond education and income: Identifying novel socioeconomic correlates of cigarette use in U.S. young adults. Prev. Med. 2017, 104, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakratsas, D.; Ambler, T. How advertising works: What do we really know? J. Mark. Res. 1999, 63, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, R.J.; Baldinger, A.L. The arf copy research validity project. J. Advert. Res. 2000, 40, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, S.A.; Noar, S.M.; Gottfredson, N.C.; Boynton, M.H.; Ribisl, K.M.; Brewer, N.T. UNC Perceived Message Effectiveness: Validation of a Brief Scale. Ann. Behav. Med. 2019, 53, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanti, A.C.; Naud, S.; West, J.C.; Pearson, J.L.; Wackowski, O.A.; Niaura, R.S.; Hair, E.; Rath, J.M. Prevalence and correlates of nicotine and nicotine product perceptions in U.S. young adults, 2016. Addict. Behav. 2019, 98, 106020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanti, A.C.; Naud, S.; West, J.C.; Pearson, J.L.; Wackowski, O.A.; Hair, E.; Rath, J.M.; Niaura, R.S. Latent Classes of Nicotine Beliefs Correlate with Perceived Susceptibility and Severity of Nicotine and Tobacco Products in US young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019, 21 (Suppl. 1), S91–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, M.A.; Villanti, A.C.; Quisenberry, A.J.; Stanton, C.A.; Doogan, N.J.; Redner, R.; Gaalema, D.E.; Kurti, A.N.; Nighbor, T.; Roberts, M.E.; et al. Tobacco Product Harm Perceptions and New Use. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20181505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, J.L.; Johnson, A.; Villanti, A.; Glasser, A.M.; Collins, L.; Cohn, A.; Rose, S.W.; Niaura, R.; A Stanton, C. Misperceptions of Harm among Natural American Spirit smokers: Results from Wave 1 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study (2013–2014). Tob. Control. 2017, 26, e61–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.L.; Moran, M.; Delnevo, C.D.; Villanti, A.C.; Lewis, M.J. Widespread Belief That Organic and Additive-Free Tobacco Products are Less Harmful Than Regular Tobacco Products: Results From the 2017 US Health Information National Trends Survey. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 21, 970–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, K.C.; Nonnemaker, J.; Duke, J.; Farrelly, M.C. Perceived effectiveness of cessation advertisements: The importance of audience reactions and practical implications for media campaign planning. Health Commun. 2013, 28, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duke, J.C.; Nonnemaker, J.M.; Davis, K.C.; Watson, K.A.; Farrelly, M.C. The impact of cessation media messages on cessation-related outcomes: Results from a national experiment of smokers. Am. J. Health Promot. 2014, 28, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, J.A.; Noar, S.M.; Sheldon, J.M.; Hall, M.G.; Kieu, T.; Brewer, N.T. Identifying Promising Themes for Adolescent Vaping Warnings: A National Experiment. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022, 24, 1379–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, M.J.; Fleischer, N.L.; Patrick, M.E. Increased nicotine vaping due to the COVID-19 pandemic among US young adults: Associations with nicotine dependence, vaping frequency, and reasons for use. Prev. Med. 2022, 159, 107059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanti, A.C.; LePine, S.E.; Peasley-Miklus, C.; West, J.C.; Roemhildt, M.; Williams, R.; Copeland, W.E. COVID-related distress, mental health, and substance use in adolescents and young adults. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health. 2022, 27, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.; Speer, J.; Taylor, N.; Alexander, T. Changes in e-cigarette use among youth and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights into risk perceptions and reasons for changing use behavior. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wackowski, O.A.; Gratale, S.K.; Jeong, M.; Delnevo, C.D.; Steinberg, M.B.; O’Connor, R.J. Over 1 year later: Smokers’ EVALI awareness, knowledge and perceived impact on e-cigarette interest. Tob. Control. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, J.C.; Silver, N.; Cappella, J.N. How did beliefs and perceptions about e-cigarettes change after national news coverage of the EVALI outbreak? PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, W.J.; Bover Manderski, M.T.; Ganz, O.; Delnevo, C.D.; Hrywna, M. Examining the Impact of Question Construction on Reporting of Sexual Identity: Survey Experiment Among Young Adults. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e32294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, T.; Riis, A.H.; Hatch, E.E.; Wise, L.A.; Nielsen, M.G.; Rothman, K.J.; Sørensen, H.T.; Mikkelsen, E.M.; Harris, K.; Nelson, E. Costs and Efficiency of Online and Offline Recruitment Methods: A Web-Based Cohort Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byaruhanga, J.; Tzelepis, F.; Paul, C.; Wiggers, J.; Byrnes, E.; Lecathelinais, C. Cost Per Participant Recruited From Rural and Remote Areas Into a Smoking Cessation Trial Via Online or Traditional Strategies: Observational Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, C.; Stevelink, S.; Fear, N. The Use of Facebook in Recruiting Participants for Health Research Purposes: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, B.N.; Rostron, B.; Johnson, S.E.; Ambrose, B.K.; Pearson, J.; Stanton, C.A.; Wang, B.; Delnevo, C.; Bansal-Travers, M.; Kimmel, H.L.; et al. Electronic cigarette use among US adults in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, 2013–2014. Tob. Control. 2017, 26, e117–e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crankshaw, E.; Gaber, J.; Guillory, J.; Curry, L.; Farrelly, M.; Saunders, M.; Hoffman, L.; Ganz, O.; Delahanty, J.; Mekos, D.; et al. Final Evaluation Findings for This Free Life, a 3-Year, Multi-Market Tobacco Public Education Campaign for Gender and Sexual Minority Young Adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022, 24, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roditis, M.L.; Dineva, A.; Smith, A.; Walker, M.; Delahanty, J.; D’Lorio, E.; Holtz, K.D. Reactions to electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS) prevention messages: Results from qualitative research used to inform FDA’s first youth ENDS prevention campaign. Tob. Control. 2020, 29, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangalang, A.; Volinsky, A.C.; Liu, J.; Yang, Q.; Lee, S.J.; Gibson, L.A.; Hornik, R.C. Identifying Potential Campaign Themes to Prevent Youth Initiation of E-Cigarettes. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, S65–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control n (%) | Intervention n (%) | Total n (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean (SD)) | 21.1 (2.0) | 21.2 (1.9) | 21.1 (1.9) | 0.76 |

| Sex | 0.76 | |||

| Male | 80 (29.5) | 90 (30.7) | 170 (30.1) | |

| Female | 191 (70.5) | 203 (69.3) | 394 (69.9) | |

| Gender identity | 0.24 | |||

| Cisgender | 259 (95.2) | 273 (92.9) | 532 (94.0) | |

| Transgender/don’t know/questioning | 13 (4.8) | 21 (7.1) | 34 (6.0) | |

| Sexual identity, not heterosexual vs. heterosexual | 0.70 | |||

| Straight/heterosexual | 191 (70.2) | 202 (68.7) | 393 (69.4) | |

| Not straight/heterosexual | 81 (29.8) | 92 (31.3) | 173 (30.6) | |

| Race/ethnicity, 3 categories | ||||

| White | 208 (76.5) | 224 (76.2) | 432 (76.3) | 0.99 |

| Non-white/other race | 24 (8.8) | 27 (9.2) | 51 (9.0) | |

| Hispanic | 40 (14.7) | 43 (14.6) | 83 (14.7) | |

| HRSA-designated rural county | 0.99 | |||

| No | 137 (51.7) | 146 (51.8) | 283 (51.7) | |

| Yes | 128 (48.3) | 136 (48.2) | 264 (48.3) | |

| Employment status | 0.16 | |||

| Work full-time (35 h/week or more) | 100 (36.8) | 103 (35.0) | 203 (35.9) | |

| Work part-time (15–34 h/week) | 70 (25.7) | 57 (19.4) | 127 (22.4) | |

| Work part-time (<15 h/week) | 39 (14.3) | 56 (19.0) | 95 (16.8) | |

| Don’t currently work for pay | 63 (23.2) | 78 (26.5) | 141 (24.9) | |

| Subjective financial status, YA only | 0.38 | |||

| Live comfortably | 95 (34.9) | 99 (33.7) | 194 (34.3) | |

| Meet needs with a little left | 99 (36.4) | 118 (40.1) | 217 (38.3) | |

| Just meet basic expenses | 74 (27.2) | 68 (23.1) | 142 (25.1) | |

| Don’t meet basic expenses | 4 (1.5) | 9 (3.1) | 13 (2.3) | |

| Ever use | ||||

| Cigarettes | 96 (35.3) | 114 (38.8) | 210 (37.1) | 0.39 |

| Electronic vapor products (EVP) | 173 (63.6) | 185 (62.9) | 358 (63.3) | 0.87 |

| Past 30-day use | ||||

| Cigarettes | 37 (13.7) | 53 (18.2) | 90 (16.0) | 0.15 |

| Electronic vapor products (EVP) | 75 (27.6) | 90 (30.6) | 165 (29.2) | 0.43 |

| Cigar/cigarillo/little cigar | 17 (6.3) | 16 (5.4) | 33 (5.8) | 0.68 |

| Smokeless tobacco | 5 (1.8) | 3 (1.0) | 8 (1.4) | 0.41 |

| Hookah or waterpipe | 7 (2.6) | 5 (1.7) | 12 (2.1) | 0.47 |

| Exposure to tobacco prevention campaigns | ||||

| The Real Cost (FDA) | 169 (62.1) | 206 (70.1) | 375 (66.3) | 0.14 |

| truth | 147 (54.0) | 169 (57.5) | 316 (55.8) | 0.28 |

| Unhyped | 50 (18.4) | 68 (23.1) | 118 (20.8) | 0.05 |

| Frequency of seeing ads or promotions for cigarettes or other tobacco products | ||||

| On the internet (mean (SD)) | 2.15 (0.78) | 2.13 (0.82) | 2.14 (0.80) | 0.79 |

| In newspapers or magazines (mean (SD)) | 1.71 (1.07) | 1.65 (1.12) | 1.68 (1.09) | 0.54 |

| On TV or streaming services (mean (SD)) | 1.76 (0.75) | 1.77 (0.76) | 1.77 (0.75) | 0.99 |

| Control n (%) | Intervention n (%) | Total n (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dwell time on messages in seconds (mean (SD)) | 133.13 (138.79) | 162.89 (164.05) | 148.59 (153.02) | 0.02 |

| Message perceptions, 1–5 scale (mean (SD)) | ||||

| Relevance | 3.19 (1.12) | 2.58 (1.26) | 2.88 (1.23) | <0.001 |

| Likeability | 3.28 (0.93) | 3.22 (0.96) | 3.25 (0.94) | 0.52 |

| Overall message rating, 1–6 scale (mean (SD)) | 3.97 (1.10) | 3.95 (1.27) | 3.96 (1.19) | 0.83 |

| Direction of messages | <0.001 | |||

| Directed to me | 70 (25.7) | 94 (32.0) | 164 (29.0) | |

| Directed to others | 58 (21.3) | 114 (38.8) | 172 (30.4) | |

| Mix | 144 (52.9) | 86 (29.3) | 230 (40.6) | |

| Value of messages | 0.001 | |||

| Mostly valuable | 82 (30.1) | 96 (32.8) | 178 (31.5) | |

| Not valuable | 38 (14.0) | 74 (25.3) | 112 (19.8) | |

| Mix | 152 (55.9) | 123 (42.0) | 275 (48.7) | |

| Message provide new information | 0.071 | |||

| No | 124 (45.6) | 112 (38.1) | 236 (41.7) | |

| Yes | 148 (54.4) | 182 (61.9) | 330 (58.3) | |

| Vaping-related responses | ||||

| Perceived message effectiveness, 1–5 scale (mean (SD)) | 2.54 (1.32) | 3.72 (0.97) | 3.15 (1.29) | <0.001 |

| Messages’ effect on curiosity to vape | <0.001 | |||

| No effect | 192 (70.6) | 120 (40.8) | 312 (55.1) | |

| Increase | 4 (1.5) | 9 (3.1) | 13 (2.3) | |

| Decrease | 76 (27.9) | 165 (56.1) | 241 (42.6) | |

| Messages’ effect on desire to quit/cut down vaping | <0.001 | |||

| No effect | 204 (75.0) | 162 (55.1) | 366 (64.7) | |

| Increase | 40 (14.7) | 100 (34.0) | 140 (24.7) | |

| Decrease | 28 (10.3) | 32 (10.9) | 60 (10.6) |

| Post-Exposure | 1-Month Follow-Up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control n (%) | Intervention n (%) | Total n (%) | p-Value | Control n (%) | Intervention n (%) | Total n (%) | p-Value | |

| Vaping-related beliefs | ||||||||

| Nicotine is main substance in EVPs that makes people want to vape | 0.11 | 0.80 | ||||||

| False | 11 (4.1) | 14 (4.8) | 25 (4.4) | 13 (5.4) | 11 (4.1) | 24 (4.7) | ||

| True | 245 (90.4) | 250 (85.0) | 495 (87.6) | 204 (84.6) | 229 (85.8) | 433 (85.2) | ||

| Don’t know | 15 (5.5) | 30 (10.2) | 45 (8.0) | 24 (10) | 27 (10.1) | 51 (10) | ||

| One 5% vape pod contains as much nicotine as pack of cigarettes | 0.22 | 0.95 | ||||||

| False | 13 (4.8) | 15 (5.1) | 28 (5.0) | 7 (2.9) | 7 (2.6) | 14 (2.7) | ||

| True | 196 (72.3) | 229 (77.9) | 425 (75.2) | 193 (79.8) | 212 (79.1) | 405 (79.4) | ||

| Don’t know | 62 (22.9) | 50 (17.0) | 112 (19.8) | 42 (17.4) | 49 (18.3) | 91 (17.8) | ||

| Addiction to nicotine is something I am concerned about | 0.39 | 0.88 | ||||||

| False | 57 (21.0) | 53 (18.0) | 110 (19.4) | 62 (25.6) | 71 (26.5) | 133 (26.1) | ||

| True | 194 (71.3) | 224 (76.2) | 418 (73.9) | 162 (66.9) | 180 (67.2) | 342 (67.1) | ||

| Don’t know | 21 (7.7) | 17 (5.8) | 38 (6.7) | 18 (7.4) | 17 (6.3) | 35 (6.9) | ||

| Vaping-related harm perceptions | ||||||||

| Harm from EVPs | 0.81 | 0.31 | ||||||

| No harm | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.0) | 4 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | ||

| A little harm | 38 (14.0) | 43 (14.6) | 81 (14.3) | 22 (9.1) | 35 (13.1) | 57 (11.2) | ||

| Some harm | 150 (55.1) | 157 (53.4) | 307 (54.2) | 131 (54.1) | 152 (56.7) | 283 (55.5) | ||

| A lot of harm | 83 (30.5) | 91 (31.0) | 174 (30.7) | 88 (36.4) | 80 (29.9) | 168 (32.9) | ||

| Harm of EVPs vs. smoking cigarettes | 0.50 | 0.72 | ||||||

| Less harmful | 71 (26.1) | 88 (29.9) | 159 (28.1) | 48 (19.8) | 49 (18.3) | 97 (19) | ||

| No different | 143 (52.6) | 141 (48.0) | 284 (50.2) | 146 (60.3) | 171 (63.8) | 317 (62.2) | ||

| More harmful | 58 (21.3) | 65 (22.1) | 123 (21.7) | 48 (19.8) | 48 (17.9) | 96 (18.8) | ||

| Harm of vaping nicotine vs. marijuana | 0.56 | 0.97 | ||||||

| Less harmful | 61 (22.4) | 58 (19.7) | 119 (21.0) | 46 (19) | 49 (18.3) | 95 (18.6) | ||

| No different | 103 (37.9) | 107 (36.4) | 210 (37.1) | 88 (36.4) | 100 (37.3) | 188 (36.9) | ||

| More harmful | 108 (39.7) | 129 (43.9) | 237 (41.9) | 108 (44.6) | 119 (44.4) | 227 (44.5) | ||

| Vaping-related norms (1 (very positive) to 5 (very negative); mean (SD)) | ||||||||

| Most people’s opinion of using EVPs like JUUL | 2.81 (0.99) | 2.85 (1.07) | 2.83 (1.03) | 0.61 | 2.87 (0.99) | 2.95 (1.03) | 2.91 (1.01) | 0.34 |

| Opinion of people who are important to you of using EVPs like JUUL | 3.48 (1.08) | 3.40 (1.11) | 3.44 (1.09) | 0.38 | 3.42 (1.13) | 3.46 (1.07) | 3.44 (1.10) | 0.70 |

| Potential spillover effects | ||||||||

| Nicotine is cause of cancer | 0.03 | 0.50 | ||||||

| False | 62 (22.8) | 55 (18.7) | 117 (20.7) | 53 (22.0) | 52 (19.4) | 105 (20.6) | ||

| True | 161 (59.2) | 204 (69.4) | 365 (64.5) | 149 (61.8) | 179 (66.8) | 328 (64.4) | ||

| Don’t know | 49 (18.0) | 35 (11.9) | 84 (14.8) | 39 (16.2) | 37 (13.8) | 76 (14.9) | ||

| Ease of use of flavored tobacco/EVPs vs. unflavored | 0.19 | 0.17 | ||||||

| Easier to use | 201 (73.9) | 207 (70.6) | 408 (72.2) | 176 (72.7) | 183 (68.3) | 359 (70.4) | ||

| About the same | 64 (23.5) | 83 (28.3) | 147 (26.0) | 66 (27.3) | 82 (30.6) | 148 (29) | ||

| Harder to use | 7 (2.6) | 3 (1.0) | 10 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.1) | 3 (0.6) | ||

| Harm of flavored tobacco/EVPs vs. unflavored | 0.20 | 0.25 | ||||||

| Less harmful | 7 (2.6) | 12 (4.1) | 19 (3.4) | 11 (4.5) | 6 (2.2) | 17 (3.3) | ||

| No different | 209 (76.8) | 207 (70.4) | 416 (73.5) | 181 (74.8) | 197 (73.5) | 378 (74.1) | ||

| More harmful | 56 (20.6) | 75 (25.5) | 131 (23.1) | 50 (20.7) | 65 (24.3) | 115 (22.5) | ||

| A tobacco product that says it has no additives is less harmful than a regular tobacco product | 0.38 | 0.03 | ||||||

| False | 140 (51.5) | 166 (56.5) | 306 (54.1) | 166 (68.6) | 153 (57.1) | 319 (62.5) | ||

| True | 49 (18.0) | 53 (18.0) | 102 (18.0) | 29 (12) | 45 (16.8) | 74 (14.5) | ||

| Don’t know | 83 (30.5) | 75 (25.5) | 158 (27.9) | 47 (19.4) | 70 (26.1) | 117 (22.9) | ||

| A tobacco product that says it is organic tobacco is less harmful than a regular tobacco product | 0.48 | 0.51 | ||||||

| False | 169 (62.1) | 196 (66.7) | 365 (64.5) | 179 (74) | 186 (69.4) | 365 (71.6) | ||

| True | 39 (14.3) | 34 (11.6) | 73 (12.9) | 22 (9.1) | 27 (10.1) | 49 (9.6) | ||

| Don’t know | 64 (23.5) | 64 (21.8) | 128 (22.6) | 41 (16.9) | 55 (10.5) | 96 (18.8) | ||

| Outcomes | n | Odds Ratio (95% CI) a |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral intentions (never users) | ||

| Try EVP soon | 158 | 0.52 (0.19–1.40) |

| Try EVP in next year | 158 | 0.67 (0.27–1.63) |

| Try cigarette soon | 185 | 0.55 (0.23–1.36) |

| Try cigarette in next year | 185 | 0.53 (0.22–1.31) |

| Behavior | ||

| Trial since baseline (never users) | ||

| EVPs | 190 | 1.27 (0.58–2.76) |

| Cigarettes | 327 | 1.19 (0.59–2.40) |

| Past 30-day use b | ||

| EVPs | 511 | 0.91 (0.49–1.70) |

| Cigarettes | 510 | 1.80 (0.83–3.89) |

| Cigar/cigarillo/little cigar | ||

| Quit or cut down in past month | ||

| EVPs | 91 | 0.95 (0.41–2.23) |

| Cigarettes | 67 | 0.74 (0.28–1.96) |

| Post-Exposure | 1-Month Follow-Up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR (95% CI) | N | OR (95% CI) | |

| Vaping-related beliefs | ||||

| Nicotine is main substance in EVPs that makes people want to vape (true vs. false/don’t know) | 294 | 0.74 (0.52–1.06) | 267 | 1.04 (0.71–1.52) |

| One 5% vape pod contains as much nicotine as pack of cigarettes (true vs. false/don’t know) | 294 | 1.31 (0.99–1.72) | 268 | 0.96 (0.69–1.33) |

| Addiction to nicotine is something I am concerned about (true vs. false/don’t know) | 294 | 1.44 (1.10–1.90) | 268 | 0.90 (0.68–1.20) |

| Vaping-related harm perceptions | ||||

| Harm from EVPs a (range 1 (no harm)–4 (a lot of harm)) | 294 | 0.056 (−0.025–0.14) | 268 | 0.14 (0.051–0.22) |

| Harm of EVPs vs. smoking cigarettes b | 294 | 268 | ||

| Less harmful | 0.64 (0.48–0.85) | 1.10 (0.77–1.57) | ||

| No different | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| More harmful | 0.78 (0.57–1.06) | 1.14 (0.80–1.64) | ||

| Harm of vaping nicotine vs. marijuana/THC b | 294 | 268 | ||

| Less harmful | 0.63 (0.45–0.87) | 0.97 (0.67–1.40) | ||

| No different | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| More harmful | 0.87 (0.66–1.15) | 1.21 (0.90–1.63) | ||

| Vaping-related norms (1 (very positive) to 5 (very negative) | ||||

| Most people’s opinion of using EVPs like JUUL a | 293 | −0.024 (−0.15–0.10) | 268 | −0.076 (−0.21–0.060) |

| Opinion of people who are important to you of using EVPs like JUUL a | 294 | 0.061 (−0.070–0.19) | 266 | −0.031 (−0.17–0.11) |

| Potential spillover effects | ||||

| Nicotine is cause of cancer (false vs. true/don’t know) | 294 | 0.75 (0.56–1.01) | 268 | 0.62 (0.45–0.86) |

| Flavored tobacco/EVPs easier to use vs. unflavored (vs. about the same/harder) | 293 | 0.85 (0.65–1.12) | 268 | 0.77 (0.57–1.04) |

| Flavored tobacco/EVPs is less harmful vs. unflavored (vs. about the same/more harmful) | 294 | 1.04 (0.57–1.90) | 268 | 0.78 (0.34–1.81) |

| A tobacco product that says it has no additives is less harmful than a regular tobacco product (false vs. true/don’t know) | 294 | 1.10 (0.86–1.39) | 268 | 1.02 (0.78–1.33) |

| A tobacco product that says it is organic tobacco is less harmful than a regular tobacco product (false vs. true/don’t know) | 294 | 0.86 (0.67–1.11) | 268 | 0.83 (0.62–1.11) |

| Behavioral intentions (never users) | ||||

| Try EVP soon | - | - | 83 | 0.82 (0.39–1.73) |

| Try EVP in next year | - | - | 83 | 0.75 (0.38–1.51) |

| Try cigarette soon | - | - | 213 | 0.52 (0.35–0.79) |

| Try cigarette in next year | - | - | 213 | 0.47 ** (0.31–0.72) |

| Behavior | ||||

| Trial since baseline (never users) | ||||

| EVPs | - | - | 101 | 0.93 (0.53–1.60) |

| Cigarettes | - | - | 165 | 1.11 (0.62–2.01) |

| Past 30-day use c | ||||

| EVPs | - | - | 268 | 1.07 (0.66–1.75) |

| Cigarettes | - | - | 267 | 0.93 (0.53–1.66) |

| Cigar/cigarillo/little cigar | 267 | 0.28 (0.12–0.67) | ||

| Quit or cut down in past month | ||||

| EVPs | - | - | 35 | 1.27 (0.57–2.85) |

| Cigarettes | - | - | 21 | 7.55 (0.83–69.0) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Villanti, A.C.; Wackowski, O.A.; LePine, S.E.; West, J.C.; Stevens, E.M.; Unger, J.B.; Mays, D. Effects of Vaping Prevention Messages on Electronic Vapor Product Beliefs, Perceived Harms, and Behavioral Intentions among Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114182

Villanti AC, Wackowski OA, LePine SE, West JC, Stevens EM, Unger JB, Mays D. Effects of Vaping Prevention Messages on Electronic Vapor Product Beliefs, Perceived Harms, and Behavioral Intentions among Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114182

Chicago/Turabian StyleVillanti, Andrea C., Olivia A. Wackowski, S. Elisha LePine, Julia C. West, Elise M. Stevens, Jennifer B. Unger, and Darren Mays. 2022. "Effects of Vaping Prevention Messages on Electronic Vapor Product Beliefs, Perceived Harms, and Behavioral Intentions among Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114182

APA StyleVillanti, A. C., Wackowski, O. A., LePine, S. E., West, J. C., Stevens, E. M., Unger, J. B., & Mays, D. (2022). Effects of Vaping Prevention Messages on Electronic Vapor Product Beliefs, Perceived Harms, and Behavioral Intentions among Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114182