Temporal Stability of Responses to the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale by Bedouin Mothers in Southern Israel

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Perinatal Depression and Disadvantaged Minorities

1.2. Bedouin in Israel

1.3. Depression Screening and Detection

1.4. Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Ethics

2.2. Study Procedures and Data Collection

2.3. Instrument

Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS)

2.4. Statistical Procedures

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamaideh, S.H. Alexithymia among Jordanian university students: Its prevalence and correlates with depression, anxiety, stress, and demographics. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2017, 54, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayers, S.; Bond, R.; Webb, R.; Miller, P.; Bateson, K. Perinatal mental health and risk of child maltreatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 98, 104172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netsi, E.; Pearson, R.M.; Murray, L.; Cooper, P.; Craske, M.G.; Stein, A. Association of Persistent and Severe Postnatal Depression with Child Outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, S. Untreated depression during pregnancy: Short- and long-term effects in offspring. A systematic review. Neuroscience 2017, 342, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okagbue, H.I.; Adamu, P.I.; Bishop, S.A.; Oguntunde, P.E.; Opanuga, A.A.; Akhmetshin, E.M. Systematic Review of Prevalence of Antepartum Depression during the Trimesters of Pregnancy. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 1555–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCall-Hosenfeld, J.S.; Phiri, K.; Schaefer, E.; Zhu, J.; Kjerulff, K. Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms throughout the Peri- and Postpartum Period: Results from the First Baby Study. J. Womens Health 2016, 25, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, N.; Naeem, H.; Tariq, A.; Naseem, S. Maternal depression and its correlates—A longitudinal study. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2021, 71, 1618–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukulskienė, M.; Žemaitienė, N. Postnatal Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Risk Following Miscarriage. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwartz, N.; O’Rourke, N.; Daoud, N. Pathways Linking Intimate Partner Violence and Postpartum Depression among Jewish and Arab Women in Israel. J. Interpers. Violence. 2020, 37, 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfayumi-Zeadna, S.; Bina, R.; Levy, D.; Merzbach, R.; Zeadna, A. Elevated Perinatal Depression during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Study among Jewish and Arab Women in Israel. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfayumi-Zeadna, S.; Kaufman-Shriqui, V.; Zeadna, A.; Lauden, A.; Shoham-Vardi, I. The Association between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Postpartum Depression Symptoms among Arab-Bedouin Women in Southern Israel. Depress. Anxiety 2014, 32, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daoud, N.; O’Brien, K.; O’Campo, P.; Harney, S.; Harney, E.; Bebee, K.; Bourgeois, C.; Smylie, J. Postpartum depression prevalence and risk factors among Indigenous, non-Indigenous and immigrant women in Canada. Can. J. Public Health 2019, 110, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfayumi-Zeadna, S.; Froimovici, M.; Rourke, N.O.; Azbarga, Z.; Okby-Cronin, R.; Salman, L.; Alkatnany, A.; Grotto, I.; Daoud, N. Direct and indirect determinants of prenatal depression among Arab-Bedouin women in Israel: The role of stressful life events and social support. Midwifery 2021, 96, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfayumi-Zeadna, S.; Froimovici, M.; Azbarga, Z.; Grotto, I.; Daoud, N. Barriers to postpartum depression treatment among Indigenous Bedouin women in Israel: A focus group study. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 27, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Central Bureau of Statistics Central Bureau of Statistics Population of Israel. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/en/mediarelease/Pages/2020/Population-of-Israel-on-the-Eve-of-2021.aspx (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Central Bureau of Statistics C “Population, by Population Group, Religion, Age and Sex, District and Sub-District”. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/doclib/2016/2.shnatonpopulation/st02_03.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Na’Amnih, W.; Romano-Zelekha, O.; Kabaha, A.; Rubin, L.P.; Bilenko, N.; Jaber, L.; Honovich, M.; Shohat, T. Continuous decrease of consanguineous marriages among Arabs in Israel. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2014, 27, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratzon, R.; Sheiner, E.; Shoham-Vardi, I. The role of prenatal care in recurrent preterm birth. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2011, 154, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnitzky, A.; Abu Ras, T. The Bedouin Population in the Negev. Israel: The Abraham Fund Initiatives. 2012. Available online: https://abrahaminitiatives.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/The-Bedouin-Population-in-the-Negev.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Amir, L.Y.; Abokaf, H.; Levy, Y.A.; Azem, F.; Sheiner, E. Bedouin Women’s Gender Preferences When Choosing Obstetricians and Gynecologists. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2016, 20, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasir, N.; Yashiv, E. The Economic Outcomes of an Ethnic Minority: The Role of Barriers. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics. 2020. Available online: https://docs.iza.org/dp13120.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Fuchs, H. Education and Employment among Young Arabs. 2017. Available online: https://www.iataskforce.org/sites/default/files/resource/resource-1560.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Elmo-Capital, J.; Almagor-Lotan, O. Data on the Employment of Arab Women with an Emphasis on Bedouins in the Negev, The Knesset Research and Information Center, Israel. 2022. Available online: https://fs.knesset.gov.il/globaldocs/MMM/9eea2a62-9152-ec11-813c-00155d0824dc/2_9eea2a62-9152-ec11-813c-00155d0824dc_11_19443.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2022). (In Hebrew)

- Shwartz, N.; Shoahm-Vardi, I.; Daoud, N. Postpartum depression among Arab and Jewish women in Israel: Ethnic inequalities and risk factors. Midwifery 2019, 70, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 757 Summary: Screening for Perinatal Depression. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 1314–1316.

- Siu, A.L.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Grossman, D.C.; Baumann, L.C.; Davidson, K.; Ebell, M.; García, F.A.R.; Gillman, M.; Herzstein, J.; Kemper, A.R.; et al. Screening for Depression in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation State-ment. JAMA 2016, 315, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levis, B.; Negeri, Z.; Sun, Y.; Benedetti, A.; Thombs, B.D. Accuracy of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for screening to detect major depression among pregnant and postpartum women: Systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ 2020, 371, m4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith-Nielsen, J.; Matthey, S.; Lange, T.; Væver, M.S. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale against both DSM-5 and ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for depression. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

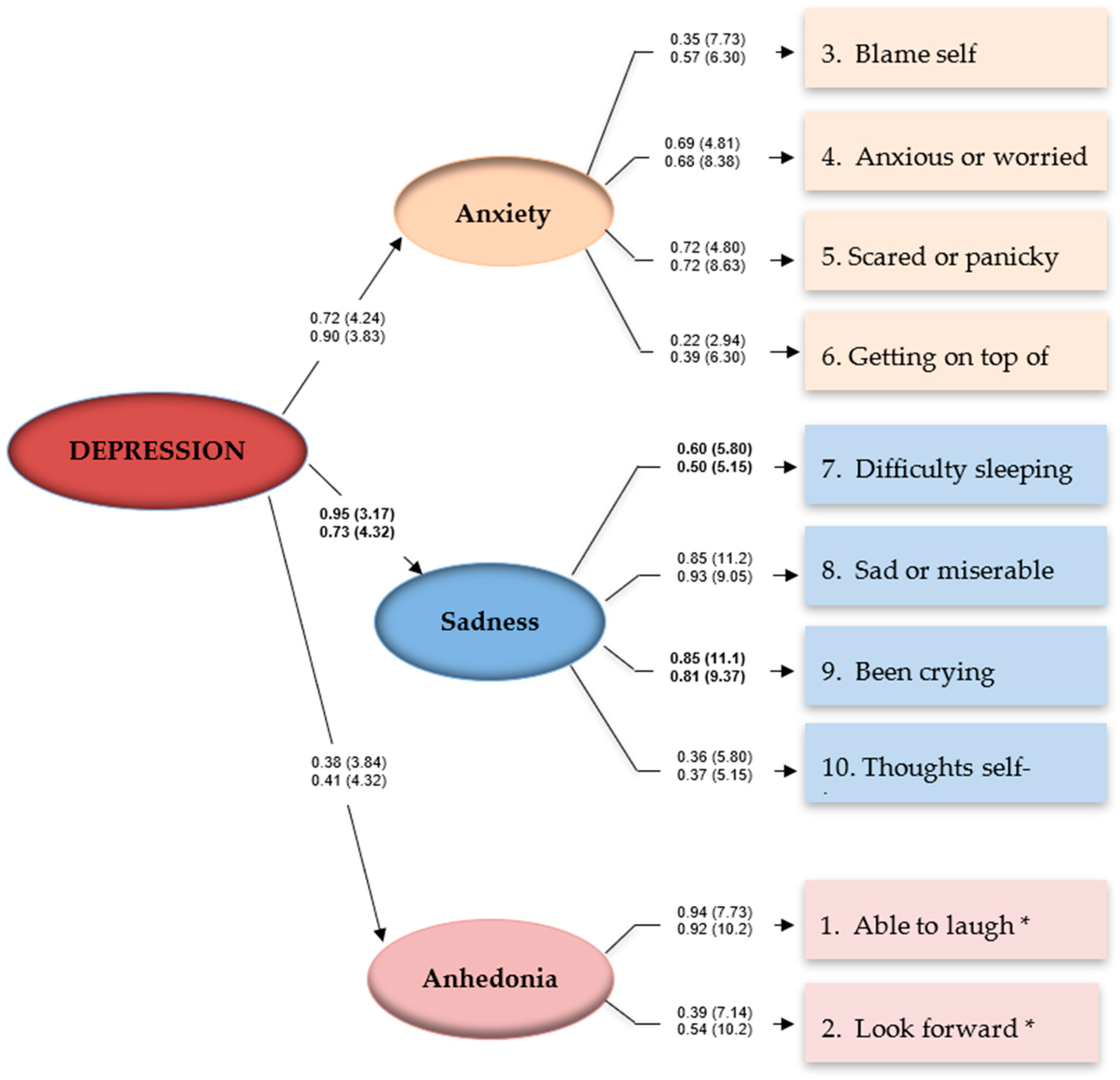

- Bina, R.; Harrington, D. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: Screening Tool for Postpartum Anxiety as Well? Findings from a Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Hebrew Version. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 20, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates, R.; Ayers, S.; de Visser, R. Factor structure of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in a population-based sample. Psychol. Assess. 2017, 29, 1016–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfayumi-Zeadna, S.; Zeadna, A.; Azbarga, Z.; Salman, L.; Froimovici, M.; Alkatnany, A.; Grotto, I.; Daoud, N. A Non-Randomized Controlled Trial for Reducing Postpartum Depression in Low-Income Minority Women at Community-Based Women’s Health Clinics. Matern. Child Health J. 2022, 26, 1689–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghubash, R.; Abou-Saleh, M.T.; Daradkeh, T.K. The validity of the Arabic Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Soc. Psychiatry 1997, 32, 474–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, C.; Inada, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Shiino, T.; Ando, M.; Aleksic, B.; Yamauchi, A.; Morikawa, M.; Okada, T.; Ohara, M.; et al. Stable factor structure of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale during the whole peripartum period: Results from a Japanese prospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, K.; Hamazaki, K.; Tsuchida, A.; Kasamatsu, H.; Inadera, H.; Kamijima, M.; Yamazaki, S.; Ohya, Y.; Kishi, R.; Yaegashi, N.; et al. Factor structure of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, N.; Bachner, Y.G.; Canham, S.L.; Sixsmith, A. BADAS Study Team Measurement equivalence of the BDSx scale with young and older adults with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 263, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications and Programing, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, N.; Hatcher, L. A Step-by-Step Approach to Using SAS for Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling; SAS Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Bowen, A.; Bowen, R.; Balbuena, L.; Feng, C.; Bally, J.; Muhajarine, N. Mood instability during pregnancy and postpartum: A systematic review. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2019, 23, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bei, B.; Coo, S.; Trinder, J. Sleep and Mood during Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period. Sleep Med. Clin. 2015, 10, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Rourke, N. Factor Structure of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale (CES–D) among Older Men and Women Who Provide Care to Persons with Dementia. Int. J. Test. 2005, 5, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-L.; Tien, Y.; Bai, Y.-S.; Lin, C.-K.; Yin, C.-S.; Chung, C.-H.; Sun, C.-A.; Huang, S.-H.; Huang, Y.-C.; Chien, W.-C.; et al. Association of Postpartum Depression with Maternal Suicide: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamama-Raz, Y.; Sommerfeld, E.; Ken-Dror, D.; Lacher, R.; Ben-Ezra, M. The role of intra-personal and in-ter-personal factors in fear of childbirth: A preliminary study. Psychiatr. Q. 2017, 88, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | N (%) | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age | 28.5 (6.1) | 15–42 | |

| 15–24 | 93 (28.0) | ||

| 25–34 | 179 (53.9) | ||

| ≥35 | 60 (18.1) | ||

| Number of children | 0–11 | ||

| 0–1 | 143 (43.1) | ||

| 2–3 | 105 (31.6) | ||

| ≥4 | 84 (25.3) | ||

| Polygamous marriages | |||

| No | 288 (86.7) | ||

| Yes | 44 (13.3) | ||

| Education | |||

| Academic degree | 49 (14.8) | ||

| Non-academic degree | 238 (85.2) | ||

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 57 (17.2) | ||

| Unemployed | 275 (82.8) | ||

| Family income (ILS/month) | |||

| ≥15,149 | 141 (42.5) | ||

| <15,149 | 191 (57.5) | ||

| Consanguineous marriage | |||

| Yes | 149 (45%) | ||

| No | 182 (55%) | ||

| Experienced miscarriages | |||

| No | 220 (65%) | ||

| Yes | 112 (35%) | ||

| Gestational age (weeks) | 29 (3.0) | 26–38 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Alpha (α) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPDS—Pregnancy | 8.07 | 5.29 | 0.80 | 0.31 | 0.75 |

| Anhedonia T1 | 1.88 | 1.67 | 0.60 | −0.42 | |

| Anxiety T1 | 3.87 | 2.56 | 0.46 | 0.98 | |

| Sadness T1 | 2.32 | 2.66 | 1.24 | 1.51 | |

| EPDS—Post Birth | 6.53 | 4.75 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.77 |

| Anhedonia T2 | 1.50 | 1.54 | 0.93 | 0.31 | |

| Anxiety T2 | 3.22 | 2.64 | 0.74 | −0.09 | |

| Sadness T2 | 1.80 | 2.09 | 1.39 | 1.51 |

| Comparison | χ2 | Δχ2 | df | Δdf | SRMR | CFI | RMSEA (90CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| baseline | 60.473 | - | 52 | - | 0.034 | 0.99 | 0.016 (0–0.030) |

| Depression—anxiety | 61.937 | 1.464 | 53 | 1 | 0.033 | 0.99 | 0.016 (0–0.031) |

| Depression—sadness | 67.230 | 5.293 * | 54 | 1 | 0.039 | 0.99 | 0.019 (0–0.033) |

| Depression—anhedonia | 67.230 | 0.096 | 54 | 1 | 0.039 | 0.99 | 0.019 (0–0.033) |

| Anxiety | |||||||

| EPDS03 | 69.181 | 1.951 | 55 | 1 | 0.041 | 0.99 | 0.020 (0–0.033) |

| EPDS04 | 74.762 | 5.581 | 56 | 1 | 0.041 | 0.99 | 0.022 (0.002–0.035) |

| EPDS05 | 78.920 | 4.158 | 57 | 1 | 0.042 | 0.99 | 0.024 (0.008–0.036) |

| EPDS06 | 78.920 | 2.270 | 57 | 1 | 0.042 | 0.99 | 0.024 (0.008–0.036) |

| Sadness | |||||||

| EPDS07 | 83.582 | 4.662 * | 58 | 1 | 0.044 | 0.99 | 0.026 (0.012–0.037) |

| EPDS08 | 85.463 | 1.881 | 59 | 1 | 0.045 | 0.99 | 0.026 (0.012–0.038) |

| EPDS09 | 92.615 | 7.152 ** | 60 | 1 | 0.045 | 0.98 | 0.029 (0.016–0.040) |

| EPDS10 | 92.615 | 0.031 | 60 | 1 | 0.045 | 0.98 | 0.029 (0.016–0.040) |

| Anhedonia | |||||||

| EPDS01 | 95.423 | 2.807 | 61 | 1 | 0.045 | 0.98 | 0.028 (0.016–0.039) |

| EPDS02 | 95.423 | 3.737 | 61 | 1 | 0.043 | 0.98 | 0.028 (0.016–0.039) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alfayumi-Zeadna, S.; O’Rourke, N.; Azbarga, Z.; Froimovici, M.; Daoud, N. Temporal Stability of Responses to the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale by Bedouin Mothers in Southern Israel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13959. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113959

Alfayumi-Zeadna S, O’Rourke N, Azbarga Z, Froimovici M, Daoud N. Temporal Stability of Responses to the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale by Bedouin Mothers in Southern Israel. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):13959. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113959

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlfayumi-Zeadna, Samira, Norm O’Rourke, Zuya Azbarga, Miron Froimovici, and Nihaya Daoud. 2022. "Temporal Stability of Responses to the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale by Bedouin Mothers in Southern Israel" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 13959. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113959

APA StyleAlfayumi-Zeadna, S., O’Rourke, N., Azbarga, Z., Froimovici, M., & Daoud, N. (2022). Temporal Stability of Responses to the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale by Bedouin Mothers in Southern Israel. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 13959. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113959