Are Children Harmed by Being Locked up at Home? The Impact of Isolation during the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Phenomenon of Domestic Violence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Violence in Cultural Terms

2.1. Europe

2.2. North America

2.3. South America

2.4. Asia and Pacific Region

2.5. Africa

3. Violence during the COVID-19 Pandemic

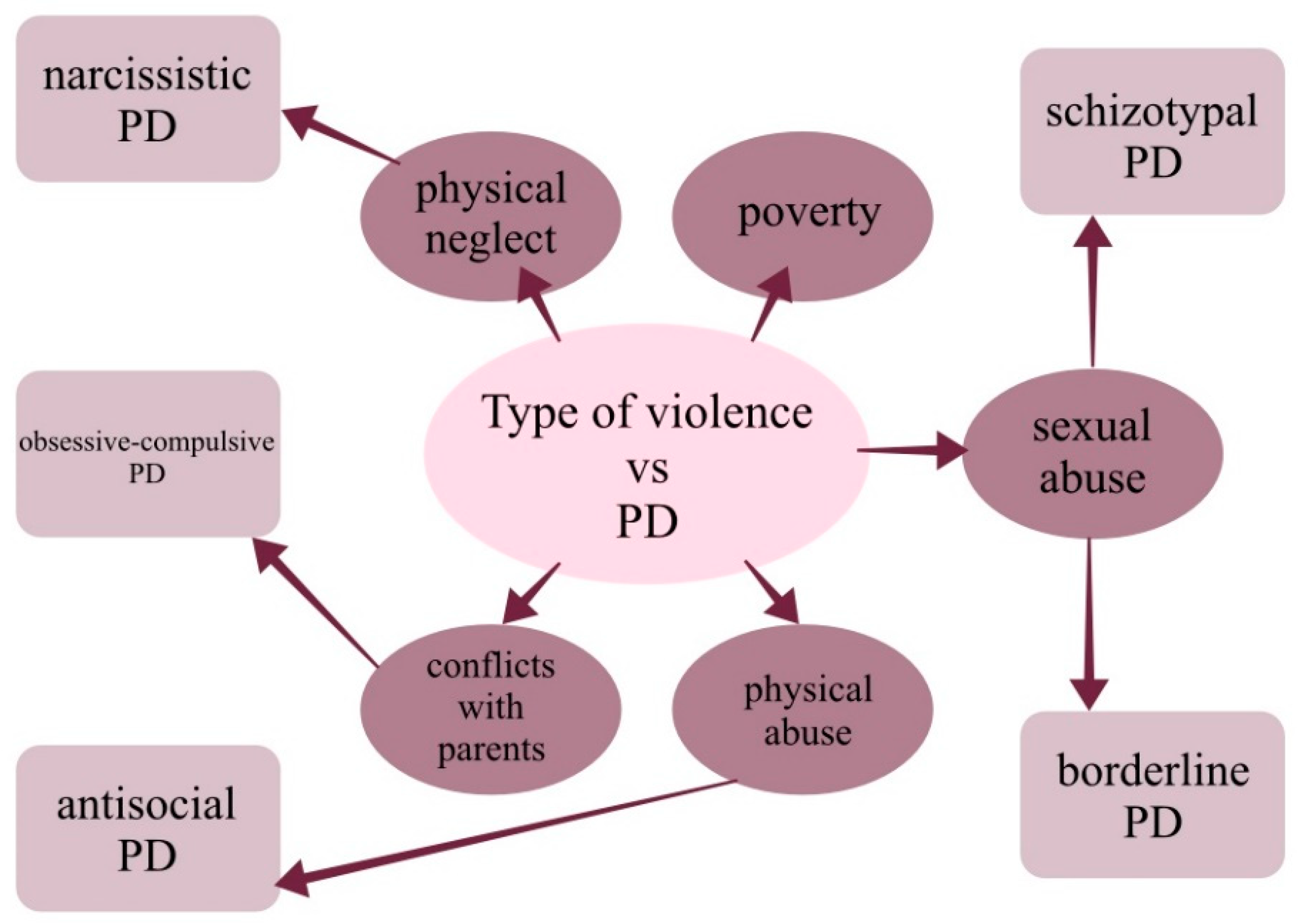

4. Numerous Consequences

5. State Tools against Violence-Institutional Help

6. What Else Can We Do?

7. From Theory to Practice

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ziegenhain, U.; Künster, A.K.; Besier, T. Gewalt gegen Kinder. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2016, 59, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, N. Les enfants, victimes à part entière des violences conjugales. Soins 2021, 6, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTavish, J.R.; MacGregor, J.C.D.; Wathen, C.N.; MacMillan, H.L. Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: An overview. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2016, 28, 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S.; Buckley, H.; Whelan, S. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abus. Negl. 2008, 32, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieger, K.; Rojas-Vilches, A.; McKinney, C.; Renk, K. The Effects and Treatment of Community Violence in Children and Adolescents. Trauma Violence Abus. 2004, 5, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashani, J.H.; Daniel, A.E.; Dandoy, A.C.; Holcomb, W.R. Family Violence: Impact on Children. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1992, 31, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forjuoh, S.N.; Zwi, A.B. Violence Against Children and Adolescents. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 1998, 45, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D.; Korbin, J. Child abuse as an international issue. Child Abus. Negl. 1988, 12, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, M. World report on violence and health: What it means for children and pediatricians. J. Pediatr. 2004, 145, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, S. Controversies and Challenges of Ritual Abuse. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2000, 38, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladd, G.W.; Cairns, E. Children: Ethnic and Political Violence. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet. Ending childhood violence in Europe. Lancet 2020, 395, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, L.L.; Græsholt-Knudsen, T.; Jørgensen, G.H.; Møller-Madsen, B.; Hansen, O.I.; Rölfing, J.D. Physical abuse of children in Denmark. Ugeskr Laeger 2021, 183, V10200795. [Google Scholar]

- Vertommen, T.; Veldhoven, N.S.-V.; Wouters, K.; Kampen, J.K.; Brackenridge, C.H.; Rhind, D.J.; Neels, K.; Eede, F.V.D. Interpersonal violence against children in sport in the Netherlands and Belgium. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 51, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivula, T.; Ellonen, N.; Janson, S.; Jernbro, C.; Huhtala, H.; Paavilainen, E. Psychological and physical violence towards children with disabilities in Finland and Sweden. J. Child Health Care 2018, 22, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsos, K.; Sakelliadis, E.I.; Zorba, E.; Tsitsika, A.; Goutas, N.; Vlachodimitropoulos, D.; Papadodima, S.; Spiliopoulou, C. Interpersonal Violence Against Children and Adolescents: A Forensic Study From Greece. Indian Pediatr. 2021, 58, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikić, J.; Beljan, P.; Milosevic, M.; Miškulin, I.; Miškulin, M.; Mujkić, A. Transgenerational Transmission of Violence among Parents of Preschool Children in Croatia. Acta Clin. Croat. 2017, 56, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives-Cases, C.; Sanz-Barbero, B.; Ayala, A.; Pérez-Martínez, V.; Sánchez-SanSegundo, M.; Jaskulska, S.; Neves, A.; Forjaz, M.; Pyżalski, J.; Bowes, N.; et al. Dating Violence Victimization among Adolescents in Europe: Baseline Results from the Lights4Violence Project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martínez, V.; Sanz-Barbero, B.; Ferrer-Cascales, R.; Bowes, N.; Ayala, A.; Sánchez-SanSegundo, M.; Albaladejo-Blázquez, N.; Rosati, N.; Neves, S.; Vieira, C.P.; et al. The Role of Social Support in Machismo and Acceptance of Violence Among Adolescents in Europe: Lights4Violence Baseline Results. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 68, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hietamäki, J.; Huttunen, M.; Husso, M. Gender Differences in Witnessing and the Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence from the Perspective of Children in Finland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, J.G.; de Amorim, L.M.; Neto, M.L.R.; Uchida, R.R.; de Moura, A.T.M.S.; Lima, N.N.R. The impact of ‘the war that drags on’ in Ukraine for the health of children and adolescents: Old problems in a new conflict? Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 128, 105602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fel, S.; Jurek, K.; Lenart-Kłoś, K. Relationship between Socio-Demographic Factors and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Cross Sectional Study among Civilian Participants’ Hostilities in Ukraine. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uğurluer, G.; Özyar, E.; Corapcioglu, F.; Miller, R.C. Psychosocial Impact of the War in Ukraine on Pediatric Cancer Patients and Their Families Receiving Oncological Care Outside Their Country at the Onset of Hostilities. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 7, 100957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olufajo, O.A.; Zeineddin, A.; Nonez, H.; Okorie, N.C.; de la Cruz, E.; Cornwell, E.E.; Williams, M. Trends in Firearm Injuries Among Children and Teenagers in the United States. J. Surg. Res. 2020, 245, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monuteaux, M.C.; Lee, L.; Fleegler, E. Children Injured by Violence in the United States: Emergency Department Utilization 2000–2008. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2012, 19, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillis, S.; Mercy, J.; Amobi, A.; Kress, H. Global Prevalence of Past-year Violence Against Children: A Systematic Review and Minimum Estimates. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20154079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin-Sommers, A.; Simmons, C.; Conley, M.; Chang, S.-A.; Estrada, S.; Collins, M.; Pelham, W.; Beckford, E.; Mitchell-Adams, H.; Berrian, N.; et al. Adolescent civic engagement: Lessons from Black Lives Matter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2109860118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaya, M.; Lesley, B.; Williams, C.; Chaves-Gnecco, D.; Flores, G. Forcible Displacement, Migration, and Violence Against Children and Families in Latin America. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 68, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelson, V.; Donnelly, P.; Morrow, W.; King, N.; Craig, W.; Pickett, W. Violence, Adolescence, and Canadian Religious Communities: A Quantitative Study. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 3613–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briceño-León, R.; Perdomo, G. Violence against indigenous children and adolescents in Venezuela. Cad. Saude Publica 2019, 35, e00084718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn-O’Brien, K.T.; Rivara, F.P.; Weiss, N.S.; Lea, V.A.; Marcelin, L.H.; Vertefeuille, J.; Mercy, J.A. Prevalence of physical violence against children in Haiti: A national population-based cross-sectional survey. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 51, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cénat, J.M.; Derivois, D.; Hébert, M.; Amédée, L.M.; Karray, A. Multiple traumas and resilience among street children in Haiti: Psychopathology of survival. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 79, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, A.J.; Sales, M.C.V. Violência contra crianças no cenário brasileiro. Cien. Saude Colet. 2016, 21, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Macedo, D.M.; Foschiera, L.N.; Bordini, T.C.P.M.; Habigzang, L.F.; Koller, S.H. Revisão sistemática de estudos sobre registros de violência contra crianças e adolescentes no Brasil. Cien. Saude Colet. 2019, 24, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Fry, D.A.; Brown, D.S.; Mercy, J.A.; Dunne, M.P.; Butchart, A.R.; Corso, P.S.; Maynzyuk, K.; Dzhygyr, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. The burden of child maltreatment in the East Asia and Pacific region. Child Abus. Negl. 2015, 42, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury-Kassabri, M. Arab youth involvement in violence: A socio-ecological gendered perspective. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 93, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanous, O. Structural Violence and its Effects on Children Living in War and Armed Conflict Zones: A Palestinian Perspective. Int. J. Health Serv. 2022, 52, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterston, T.; Nasser, D. Access to healthcare for children in Palestine. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2017, 1, e000115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghossain, T.; Bott, S.; Akik, C.; Ghattas, H.; Obermeyer, C.M. Prevalence of Key Forms of Violence Against Adolescents in the Arab Region: A Systematic Review. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 64, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, O.T.; Abbas, A.K.; Eid, H.O.; Salem, M.O.; Abu-Zidan, F.M. Interpersonal violence in the United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Inj. Contr. Saf. Promot. 2014, 21, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhi, P.; Saini, A.G.; Malhi, P. Child maltreatment in India. Paediatr Int. Child Health 2013, 33, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, R.N. Children at Work, Child Labor and Modern Slavery in India: An Overview. Indian Pediatr. 2019, 56, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.-H.; Kim, K.-I.; Park, Y.-C.; Zhang, L.D.; Lu, M.K.; Li, D. Children’s experience of violence in China and Korea: A transcultural study. Child Abus. Negl. 2000, 24, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Zheng, X.; Fry, D.A.; Ganz, G.; Casey, T.; Hsiao, C.; Ward, C.L. The Economic Burden of Violence against Children in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, L.M.; Rockey, J.C.; Rockowitz, S.R.; Kanja, W.; Colloff, M.F.; Flowe, H.D. Children’s Vulnerability to Sexual Violence During COVID-19 in Kenya: Recommendations for the Future. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2021, 2, 630901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cluver, L.D.; Rudgard, W.E.; Toska, E.; Zhou, S.; Campeau, L.; Shenderovich, Y.; Orkin, M.; Desmond, C.; Butchart, A.; Taylor, H.; et al. Violence prevention accelerators for children and adolescents in South Africa: A path analysis using two pooled cohorts. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cluver, L.; Shenderovich, Y.; Meinck, F.; Berezin, M.; Doubt, J.; Ward, C.; Parra-Cardona, J.; Lombard, C.; Lachman, J.; Wittesaele, C.; et al. Parenting, mental health and economic pathways to prevention of violence against children in South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 262, 113194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njelesani, J.; Hashemi, G.; Cameron, C.; Cameron, D.; Richard, D.; Parnes, P. From the day they are born: A qualitative study exploring violence against children with disabilities in West Africa. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherr, L.; Hensels, I.S.; Skeen, S.; Tomlinson, M.; Roberts, K.J.; Macedo, A. Exposure to violence predicts poor educational outcomes in young children in South Africa and Malawi. Int. Health 2015, 8, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, R.; Dubey, M.J.; Chatterjee, S.; Dubey, S. Impact of COVID-19 on children: Special focus on the psychosocial aspect. Minerva Pediatr. 2020, 72, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillis, S.D.; Unwin, H.J.T.; Chen, Y.; Cluver, L.; Sherr, L.; Goldman, P.S.; Ratmann, O.; Donnelly, C.A.; Bhatt, S.; Villaveces, A.; et al. Global minimum estimates of children affected by COVID-19-associated orphanhood and deaths of caregivers: A modelling study. Lancet 2021, 398, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrowski, N.; Cappa, C.; Pereira, A.; Mason, H.; Daban, R.A. Violence against children during COVID-19: Assessing and understanding change in use of helplines. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 116, 104757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AboKresha, S.A.; Abdelkreem, E.; Ali, R.A.E. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic and related isolation measures on violence against children in Egypt. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 2021, 96, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereda, N.; Díaz-Faes, D.A. Family violence against children in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic: A review of current perspectives and risk factors. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, I.; Bennett, D.; Taylor-Robinson, D.C. Children are being sidelined by COVID-19. BMJ 2020, 369, m2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Jones, A.R.; Bowen, A.C.; Danchin, M.; Koirala, A.; Sharma, K.; Yeoh, D.K.; Burgner, D.P.; Crawford, N.W.; Goeman, E.; Gray, P.E.; et al. COVID-19 in children: Epidemiology, I.; prevention and indirect impacts. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2022, 58, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, E.S.; de Moraes, C.L.; Hasselmann, M.H.; Deslandes, S.F.; Reichenheim, M.E. A violência contra mulheres, crianças e adolescentes em tempos de pandemia pela COVID-19: Panorama, motivações e formas de enfrentamento. Cad. Saude Publica 2020, 36, e00074420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, C.; Bhatia, A.; Petzold, M.; Jugder, M.; Guedes, A.; Cappa, C.; Devries, K. Modelling the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on violent discipline against children. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 116, 104897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, M.R.; Grigorian, A.; Swentek, L.; Arora, J.; Kuza, C.M.; Inaba, K.; Kim, D.; Lekawa, M.; Nahmias, J. Firearm violence against children in the United States: Trends in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022, 92, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro-Ruiz, J.P.; Ordóñez-Camblor, N. Effects of Covid-19 confinement on the mental health of children and adolescents in Spain. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappa, C.; Jijon, I. COVID-19 and violence against children: A review of early studies. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 116, 105053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fegert, J.M.; Vitiello, B.; Plener, P.L.; Clemens, V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, C.; Hu, R.; Zhu, T. “The Hidden Pandemic of Family Violence During COVID-19: Unsupervised Learning of Tweets. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e24361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourti, A.; Stavridou, A.; Panagouli, E.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Spiliopoulou, C.; Tsolia, M.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Tsitsika, A. Domestic Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021, 152483802110386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, S.M.T.; Galdeano, E.A.; da Trindade, E.M.G.G.; Fernandez, R.S.; Buchaim, R.L.; Buchaim, D.V.; da Cunha, M.R.; Passos, S.D. Epidemiological Study of Violence against Children and Its Increase during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, A.; Fabbri, C.; Cerna-Turoff, I.; Turner, E.; Lokot, M.; Warria, A.; Tuladhar, S.; Tanton, C.; Knight, L.; Lees, S.; et al. Violence against children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021, 99, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, F.; Büechl, V.C.S.; Rehberg, F.; Mojahed, A.; Daniels, J.K.; Schellong, J.; Garthus-Niegel, S. Changes in Prevalence and Severity of Domestic Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengasamy, E.R.; Long, S.A.; Rees, S.C.; Davies, S.; Hildebrandt, T.; Payne, E. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown: Domestic and child abuse in Bridgend. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 130, 105386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrary, J.; Sanga, S. The Impact of the Coronavirus Lockdown on Domestic Violence. Am. Law Econ. Rev. 2021, 23, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierolf, B.; Geurts, E.; Steketee, M. Domestic violence in families in the Netherlands during the coronavirus crisis: A mixed method study. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 116, 104800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.E. Unemployment and child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Republic of Korea. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 130, 105474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machlin, L.; Gruhn, M.A.; Miller, A.B.; Milojevich, H.M.; Motton, S.; Findley, A.M.; Patel, K.; Mitchell, A.; Martinez, D.N.; Sheridan, M.A. Predictors of family violence in North Carolina following initial COVID-19 stay-at-home orders. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 130, 105376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, I.; Priolo-Filho, S.; Katz, C.; Andresen, S.; Bérubé, A.; Cohen, N.; Connell, C.M.; Collin-Vézina, D.; Fallon, B.; Fouche, A.; et al. One year into COVID-19: What have we learned about child maltreatment reports and child protective service responses? Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 130, 105473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillis, S.D.; Mercy, J.A.; Saul, J.R. The enduring impact of violence against children. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker-Descartes, I.; Mineo, M.; Condado, L.V.; Agrawal, N. Domestic Violence and Its Effects on Women, Children, and Families. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 68, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, R.; Widom, C.S.; Browne, K.; Fergusson, D.; Webb, E.; Janson, S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet 2009, 373, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćurčić-Hadžagić, N. Psychological Consequences in Abused and Neglected School Children Exposed to Family Violence. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020, 32, 367–370. [Google Scholar]

- Rivara, F.; Adhia, A.; Lyons, V.; Massey, A.; Mills, B.; Morgan, E.; Simckes, M.; Rowhani-Rahbar, A. The Effects of Violence on Health. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 1622–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, V.A.; Chandra, P.S.; Vaddiparti, K. Mental health consequences of violence against women and girls. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2015, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengartner, M.P.; Ajdacic-Gross, V.; Rodgers, S.; Müller, M.; Rössler, W. Childhood adversity in association with personality disorder dimensions: New findings in an old debate. Eur. Psychiatry 2013, 28, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, M.; Tonmyr, L.; Hovdestad, W.E.; Gonzalez, A.; MacMillan, H. Exposure to family violence from childhood to adulthood. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, P.; Franceschini, G.; Villani, A.; Corsello, G. “Physical, psychological and social impact of school violence on children. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2019, 45, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, L.; Landis, D. Violence against children in humanitarian settings: A literature review of population-based approaches. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 152, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, C.M.; O’Leary, P.; Lakhani, A.; Osborne, J.M.; de Souza, L.; Hope, K.; Naimi, M.S.; Khan, H.; Jawad, Q.S.; Majidi, S. Violence Against Children in Afghanistan: Community Perspectives. J Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 2521–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. The psychosocial consequences for children of mass violence, terrorism and disasters. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2007, 19, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimber, M.; McTavish, J.R.; Couturier, J.; Boven, A.; Gill, S.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Macmillan, H.L. Consequences of child emotional abuse, emotional neglect and exposure to intimate partner violence for eating disorders: A systematic critical review. BMC Psychol. 2017, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, A.; Agastya, N.L.P.M.; Cislaghi, B.; Schulte, M.-C. Special Symposium: Social and gender norms and violence against children: Exploring their role and strategies for prevention. Glob. Public Health 2021, 16, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, S.; Muhammad, T.; Goldhagen, J.; Seth, R.; Kadir, A.; Bennett, S.; D’Annunzio, D.; Spencer, N.J.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Gerbaka, B. Ending violence against children: What can global agencies do in partnership? Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 119, 104733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawar, Y.R.; Shiffman, J. A global priority: Addressing violence against children. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021, 99, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, S.M.; Branas, C.C.; Formica, M.K. Community-Engaged and Informed Violence Prevention Interventions. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 68, 489–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colucci, E.; Hassan, G. Prevention of domestic violence against women and children in low-income and middle-income countries. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2014, 27, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efevbera, Y.; McCoy, D.C.; Wuermli, A.J.; Betancourt, T.S. Integrating Early Child Development and Violence Prevention Programs: A Systematic Review. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2018, 2018, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osofsky, J.D. Prevalence of children’s exposure to domestic violence and child maltreatment: Implications for prevention and intervention. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 6, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falconer, N.S.; Casale, M.; Kuo, C.; Nyberg, B.J.; Hillis, S.D.; Cluver, L.D. Factors That Protect Children From Community Violence: Applying the INSPIRE Model to a Sample of South African Children. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 11602–11629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.J.; Braciszewski, J.M. Community Violence Prevention and Intervention Strategies for Children and Adolescents: The Need for Multilevel Approaches. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2009, 37, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, M.A.; Silva, M.A.C.; de Paiva, A.C.O.; da Silva, D.M.; Alves, M. Práticas profissionais em situações de violência na atenção domiciliar: Revisão integrativa. Cien. Saude Colet. 2020, 25, 3587–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, L. Interviewing the Young Child Sexual Abuse Victim. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 1995, 33, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leserman, J. Sexual Abuse History: Prevalence, Health Effects, Mediators, and Psychological Treatment. Psychosom. Med. 2005, 67, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkins, C.; Drinkwater, J.; Hester, M.; Stanley, N.; Szilassy, E.; Feder, G. General practice clinicians’ perspectives on involving and supporting children and adult perpetrators in families experiencing domestic violence and abuse. Fam. Pract. 2015, 32, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatuguta, A.; Colombini, M.; Seeley, J.; Soremekun, S.; Devries, K. Supporting children and adolescents who have experienced sexual abuse to access services: Community health workers’ experiences in Kenya. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 116, 104244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodley, D.; Runswick-Cole, K. The violence of disablism. Sociol. Health Illn. 2011, 33, 602–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, H.; Rapee, R.; Todorov, N. Forgiveness Reduces Anger in a School Bullying Context. J. Interpers. Violence 2017, 32, 1642–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, N.; Naeem, M.; Zehra, A. Professional team response to violence against children: From experts to teamwork. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 119, 104777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Figueiredo, C.S.; Sandre, P.C.; Portugal, L.C.L.; Mázala-De-Oliveira, T.; da Chagas, L.S.; Raony, Í.; Ferreira, E.S.; Giestal-De-Araujo, E.; dos Santos, A.A.; Bomfim, P.O.-S. COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents’ mental health: Biological, environmental, and social factors. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 106, 110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, K.; Jones, C.B.; Bhullar, N.; Durkin, J.; Gyamfi, N.; Fatema, S.R.; Jackson, D. COVID-19 and family violence: Is this a perfect storm? Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modifiable Factors | Non-Modifiable Factors |

|---|---|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grzejszczak, J.; Gabryelska, A.; Gmitrowicz, A.; Kotlicka-Antczak, M.; Strzelecki, D. Are Children Harmed by Being Locked up at Home? The Impact of Isolation during the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Phenomenon of Domestic Violence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113958

Grzejszczak J, Gabryelska A, Gmitrowicz A, Kotlicka-Antczak M, Strzelecki D. Are Children Harmed by Being Locked up at Home? The Impact of Isolation during the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Phenomenon of Domestic Violence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):13958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113958

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrzejszczak, Jagoda, Agata Gabryelska, Agnieszka Gmitrowicz, Magdalena Kotlicka-Antczak, and Dominik Strzelecki. 2022. "Are Children Harmed by Being Locked up at Home? The Impact of Isolation during the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Phenomenon of Domestic Violence" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 13958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113958

APA StyleGrzejszczak, J., Gabryelska, A., Gmitrowicz, A., Kotlicka-Antczak, M., & Strzelecki, D. (2022). Are Children Harmed by Being Locked up at Home? The Impact of Isolation during the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Phenomenon of Domestic Violence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 13958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113958