Ultra-Orthodox Women in the Job Market: What Helps Them to Become Healthy and Satisfied?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. The Ecological Model

1.1.2. Microsystem—Family Quality of Life

1.1.3. Mesosystem—Community Sense of Coherence

1.1.4. Exosystem—Diversity Perceptions and Inclusive Leadership

1.2. Outcomes: Job Satisfaction and Mental Health

1.2.1. Job Satisfaction

1.2.2. Mental Health

1.3. Research Questions

- Are there differences between Ultra-Orthodox women who work within the Ultra-Orthodox enclave, those who work with the Ultra-Orthodox sector and other sectors of Israel society, and those who work mainly outside the Ultra-Orthodox enclave, in terms of family quality of life, community sense of coherence, diversity perception, inclusive leadership, job satisfaction, and/or mental health [2,3]?

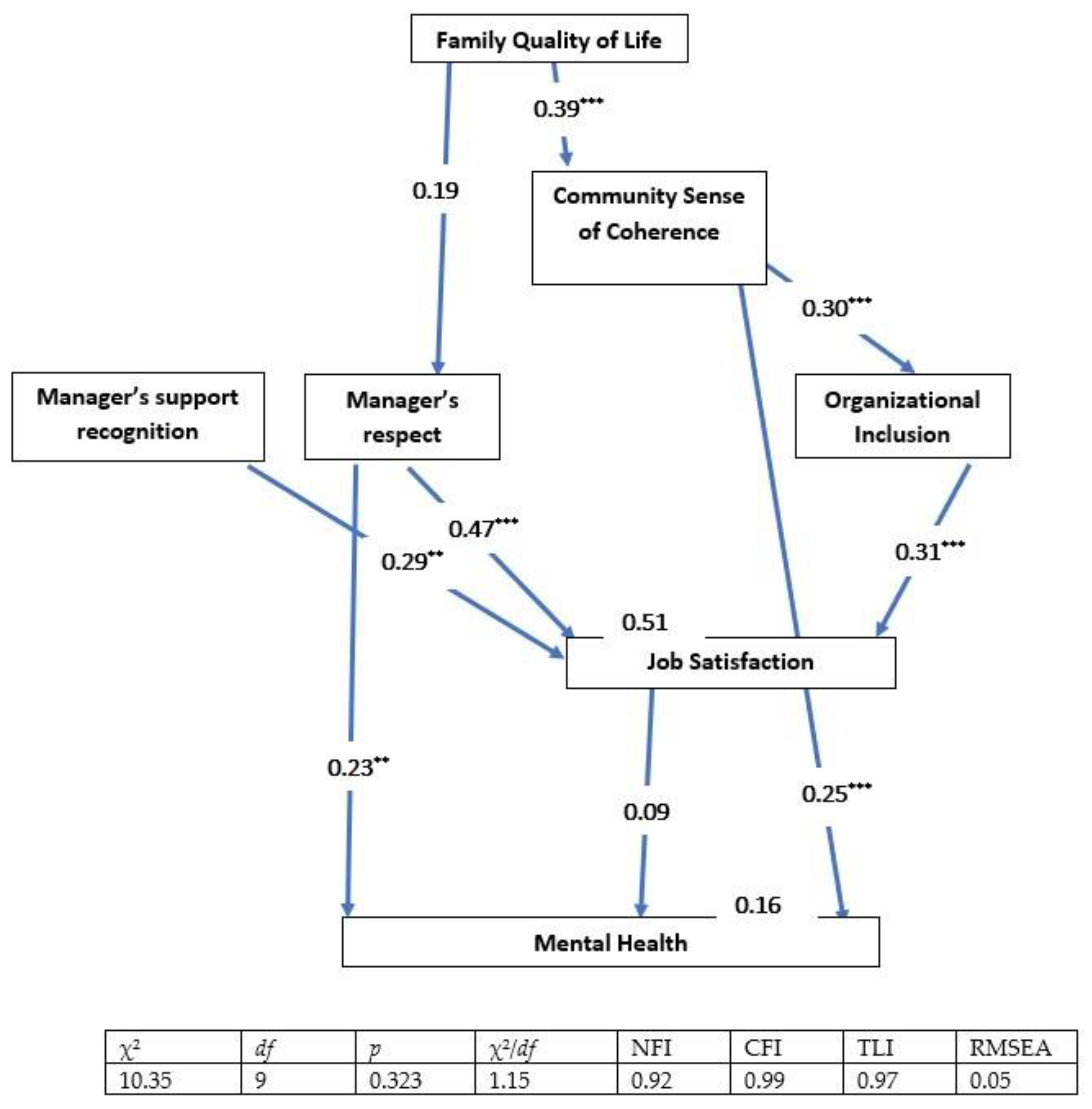

- Based on the ecological model that evaluates the different circles of one’s life as promoting one’s mental health, we built a model that included the main study variables: Family Quality of Life, Community Sense of Coherence, Diversity Perceptions subscales, and Inclusive Leadership subscales as potential explanatory factors of employees’ satisfaction from work and their mental health. The two dependent variables (i.e., job satisfaction and mental health) were examined separately [4,5,8].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographic Data

2.3.2. The Family Quality of Life Scale (FQOL)

2.3.3. Sense of Community Coherence

2.3.4. Diversity-Perceptions Scale

2.3.5. Inclusive Leadership Scale (ILS)

2.3.6. Employee Satisfaction Inventory (ESI)

2.3.7. General Health Construct (GHQ-12)

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

4.2. Study Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sue, D.W.; Sue, D. Counseling the Culturally Diverse: Theory & Practice, 6th ed.; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, E.C.; Banks, K.H. The color and texture of hope: Some preliminary findings and implications for hope theory and counseling among diverse racial/ethnic groups. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minority Psychol. 2007, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Youssef-Morgan, C.M.; Hardy, J. A positive approach to multiculturalism and diversity management in the workplace. In Perspectives on the Intersection of Multiculturalism and Positive Psychology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academ. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Hunter, E.M.; Ferguson, M.; Whitten, D. Work–family enrichment and satisfaction: Mediating processes and relative impact of originating and receiving domains. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 845–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, X.W.; Kalliath, T.; Brough, P.; Siu, O.L.; O’Driscoll, M.P.; Timms, C. Work–family enrichment and satisfaction: The mediating role of self-efficacy and work–life balance. Int. J. Human Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 1755–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Elfassi, Y.; Braun-Lewensohn, O.; Krumer-Nevo, M.; Sagy, S. Community sense of coherence among adolescents as related to their involvement in risk behaviors. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 44, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Lewensohn, O. Inclusion in Israel: Coping resources and job satisfaction as explanatory factors of stress in two cultural groups. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Need. 2015, 15, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Lewensohn, O.; Bar, R. Coping and quality of life among military wives following a military operation. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 254, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Lewensohn, O.; Kalagy, T. Between the inside and the outside world: Coping of Ultra-Orthodox individuals with their work environment after academic studies. Community Ment. Health 2019, 55, 894–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meuse, K.P.; Hostager, T.J. Developing an instrument for measuring attitude for and perceptions of workplace diversity: An initial report. Human Resour. Dev. Q. 2001, 12, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, T., Jr. The multicultural organization. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1991, 5, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; De Dreu, C.K.; Homan, A.C. Work group diversity and group performance: An integrative model and research agenda. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antwi-Boasiako, K.B. The dilemma of hiring minorities and conservative resistance: The diversity game. J. Instruct. Psychol. 2008, 35, 429–440. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K.M.; Plaut, V.C. The many faces of diversity resistance in the workplace. In Diversity Resistance in Organizations; Thomas, K.M., Ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; Schippers, M.C. Work group diversity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 515–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Friedman, H.H.; Friedman, L.W.; Amoo, T. Using humor in the introductory statistics course. J. Stat. Educ. 2002, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofhuis, J.; van der Zee, K.I.; Otten, S. Measuring employee perception on the effects of cultural diversity at work: Development of the benefits and threats of diversity scale. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phillips, L.T.; Slepian, M.L.; Hughes, B.L. Perceiving groups: The people perception of diversity and hierarchy. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 114, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Palmon, R.; Ziv, E. Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological safety. Creativ. Res. J. 2010, 22, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D. Setting the Table; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander, E.P. Inclusive Leadership: The Essential Leader-Follower Relationship; Routledge: London, UK; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander, E.P.; Park, B.B.; Elman, B.; Ignagni, M.E. Inclusive leadership and leader-follower relations: Concepts, research, and applications. Memb. Connect. Int. Lead. Assoc. 2008, 5, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.B.; Tran, T.B.H.; Kang, S.W. Inclusive leadership and employee well-being: The mediating role of person-job fit. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 18, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koustelios, A.D.; Bagiatis, K. The Employee Satisfaction Inventory (ESI): Development of a scale to measure satisfaction of Greek employees. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1997, 57, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malach Pines, A. A psychoanalytic-existential approach to burnout: Demonstrated in the cases of a nurse, a teacher, and a manager. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 2002, 39, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Thoresen, C.J.; Bono, J.E.; Patton, G.K. The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, P.; Peasgood, T.; White, M. Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. J. Econ. Psychol. 2008, 29, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madera, J.M.; Dawson, M.; Guchait, P. Psychological diversity climate: Justice, racioethnic minority status and job satisfaction. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 31, 1083–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, F.A. Psychological well-being: Evidence regarding its causes and consequences. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2009, 1, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Roberts, L.M.; Bednar, J. Prosocial practices, positive identity, and flourishing at work. In Applied Positive Psychology: Improving Everyday Life, Health, Schools, Work, and Society; Donaldson, S.I., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Nakamura, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan, J.N.; Still, M. Relationships between burnout, turnover intention, job satisfaction, job demands and job resources for mental health personnel in an Australian mental health service. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S.; Joyce, S.; Tan, L.; Johnson, A.; Nguyen, H.; Modini, M.; Groth, M. Developing a Mentally Healthy Workplace: A Review of the Literature; National Mental Health Commission and the Mentally Healthy Workplace Alliance: Sydney, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Summers, J.A.; Turnbull, A.; Zuna, N. The quantitative measurement of family quality of life: A review of available instruments. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 1098–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Lewensohn, O.; Sagy, S. Salutogenesis and culture: Personal and community sense of coherence in different cultural groups. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2011, 23, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barak, M.E.; Cherin, D.A.; Berkman, S. Organizational and personal dimensions in diversity climate: Ethnic and gender differences in employee perceptions. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1998, 34, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, E.P. Relating leadership to active followership. In Reflections on Leadership; Couto, R.A., Ed.; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007; pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L.R. BSI—Brief Symptom Inventory. In Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual; National Computer Systems: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Savitz, K.L. The SCL–90–R and Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) in Primary Care; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Carmines, E.G.; McIver, J.P. Analyzing models with unobserved variables. In Social Measurement: Current Issues; Bohrnstedt, G.W., Borgatta, E.F., Eds.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R.H. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Thoughts on the relations between emotion and cognition. Amer. Psychol. 1982, 37, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Within the Enclave (a) N ≈ 131 | Both (b) N ≈ 68 | Outside the Enclave (c) N ≈ 105 | F | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Family quality of life (1–5) | 4.00 | 0.61 | 4.02 | 0.64 | 3.87 | 0.65 | 1.76 |

| Community sense of coherence (1–7) | 5.30 | 0.92 | 5.08 | 1.05 | 4.98 | 1.10 | 3.10 *(ac) |

| Diversity perceptions (1–6) | 4.26 | 0.73 | 4.06 | 0.75 | 4.33 | 0.69 | 2.96 ^(bc) |

| Organization fairness (1–6) | 4.75 | 1.14 | 4.34 | 1.31 | 4.70 | 1.12 | 2.91 ^(ab) |

| Organizational inclusion (1–6) | 2.79 | 1.00 | 2.67 | 0.93 | 2.90 | 0.90 | 1.16 |

| Personal diversity values (1–6) | 4.01 | 1.25 | 4.03 | 1.45 | 4.31 | 1.24 | 1.69 |

| Inclusive leadership (1–5) | 3.77 | 0.65 | 3.61 | 0.72 | 3.90 | 0.65 | 4.08 *(bc) |

| Support-Recognition (1–5) | 3.70 | 0.95 | 3.55 | 0.86 | 3.89 | 0.85 | 3.17 *(bc) |

| Communication-Action-Fairness (1–5) | 3.57 | 0.78 | 3.55 | 0.79 | 3.72 | 0.71 | 1.46 |

| Respect for the worker (1–5) | 4.06 | 0.74 | 3.73 | 0.91 | 4.09 | 0.82 | 4.05 *(ab, bc) |

| General health (1–5) | 3.33 | 0.48 | 3.25 | 0.55 | 3.20 | 0.52 | 1.95 |

| Work satisfaction (1–5) | 3.58 | 0.73 | 3.42 | 0.77 | 3.63 | 0.79 | 1.62 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kalagy, T.; Abu-Kaf, S.; Braun-Lewensohn, O. Ultra-Orthodox Women in the Job Market: What Helps Them to Become Healthy and Satisfied? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8092. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138092

Kalagy T, Abu-Kaf S, Braun-Lewensohn O. Ultra-Orthodox Women in the Job Market: What Helps Them to Become Healthy and Satisfied? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(13):8092. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138092

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalagy, Tehila, Sarah Abu-Kaf, and Orna Braun-Lewensohn. 2022. "Ultra-Orthodox Women in the Job Market: What Helps Them to Become Healthy and Satisfied?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 13: 8092. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138092

APA StyleKalagy, T., Abu-Kaf, S., & Braun-Lewensohn, O. (2022). Ultra-Orthodox Women in the Job Market: What Helps Them to Become Healthy and Satisfied? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 8092. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138092