Oral and Mucosal Complaints among Institutionalized Care Seniors in Malopolska Voivodeship—The Utility of the Mirror Sliding Test in an Assessment of Dry Mouth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Decrease in Saliva

3.2. Taste Disorders

3.3. Difficulty in Taking Food

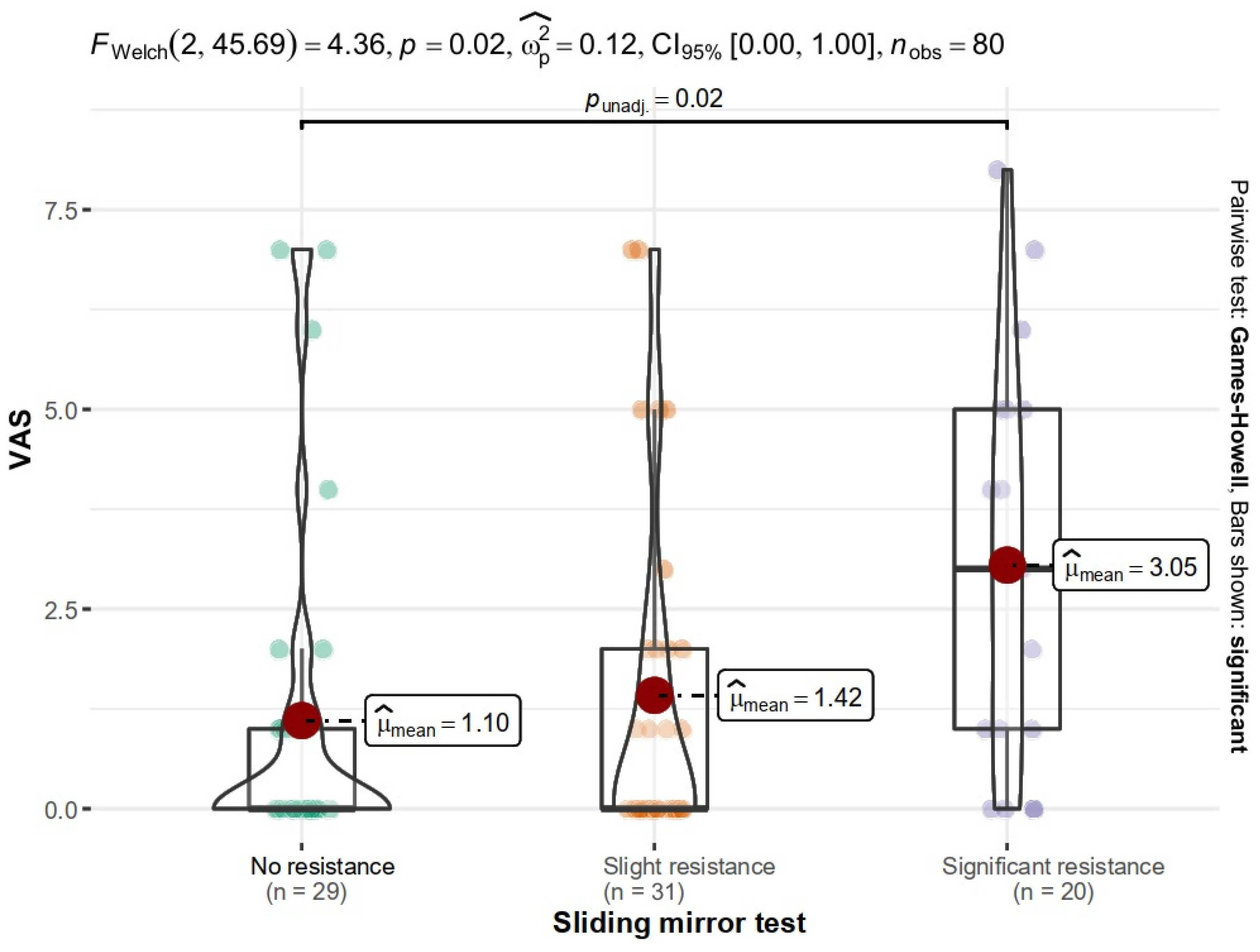

3.4. Oral Pain

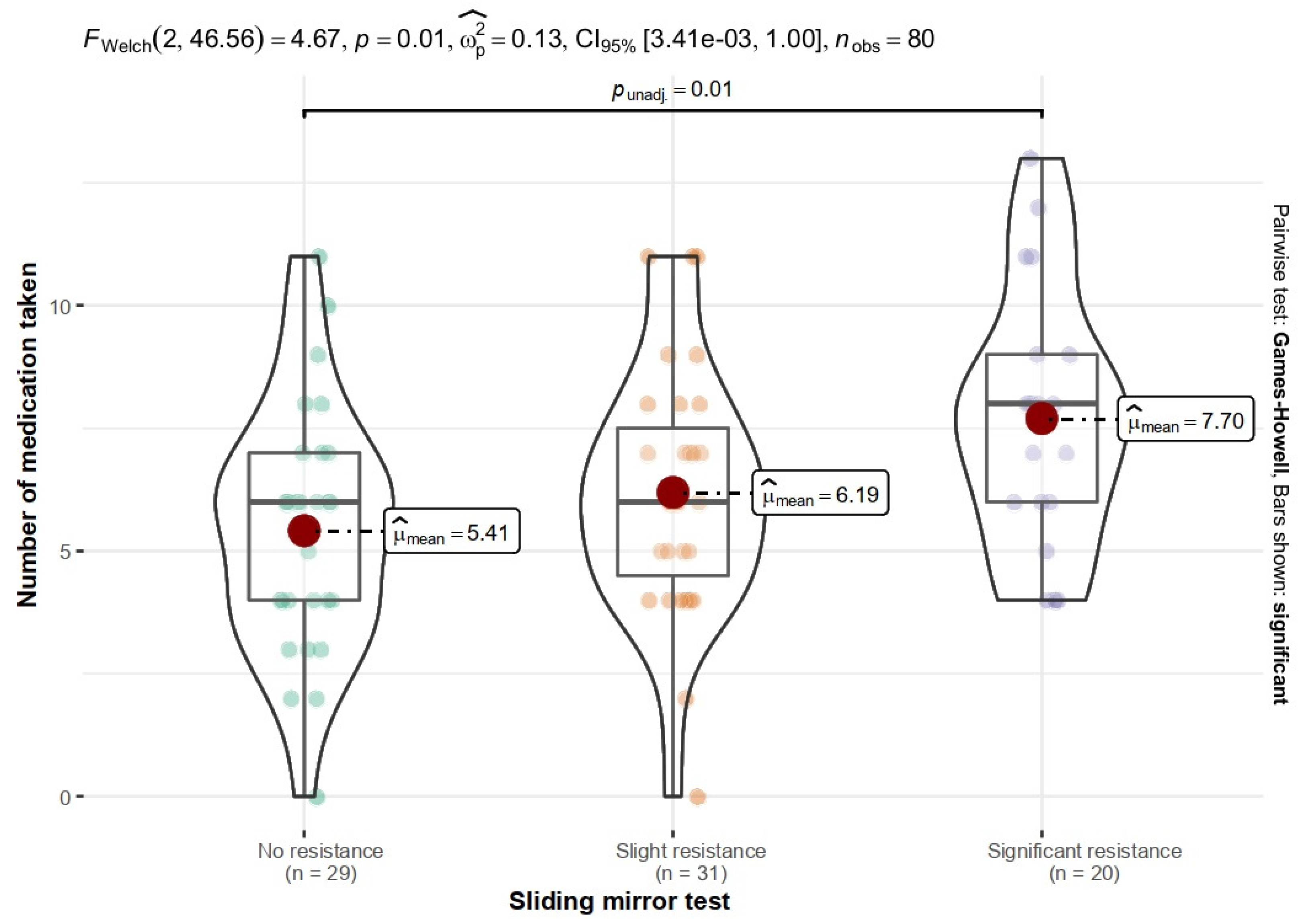

3.5. Number of Medications Taken

- Regardless of the time of day, patients with slight and significant resistance showed more frequent dry mouth.

- There was a significant difference in the need to hold a glass of water at the bedside between patients with no and slight resistance.

- Patients with no resistance showed the lowest proportion in a need of drinking water after a dry meal (10.3%). This difference was significant compared to both slight (54.8%) and high resistance (85%) patients.

- Patients with no resistance were the least likely to have mucosal dryness while eating and thus the least likely to have swallowing disorders.

- Patients with significant resistance had a need for candy to reduce feelings of dryness.

- Patients with slight and significant resistance found the amount of saliva too low and show the need to moisten the mouth.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mucosal Burning

4.2. Polypharmacy

4.3. Taste Disorders

4.4. Difficulty in Taking Food

4.5. Dry Mouth

4.6. Sliding Mirror Test

5. Conclusions

- Dryness, taste and food intake impairment and mucosal burning are symptoms associated with seniors, and their frequency does not depend on the type of care. The propability of mucosal burning and difficulty in using dental restorations increases with the length of stay at MHCOD.

- Senior patients are at risk for side effects of polypharmacy, which increases the risk of dry mouth and taste disorders. Seniors with higher levels of dry mouth are more likely to exhibit mucosal burning and difficulty taking food.

- The implementation of the sliding mirror test in the scope of the primary care geriatric examination should be discussed. The results confirmed that this test can be used to assess dry mouth and related symptoms. We showed correlations between the sliding mirror test result and: taste disorders, problems with food intake, intensity of pain, and number of medications taken. The use of sliding mirror test will allow the rapid and inexpensive screening of patients for mucosal dryness and prevention of the impact of dry mouth on the quality of life of senior patients.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harwood, R.H.; Sayer, A.A.; Hirschfeld, M. Current and Future Worldwide Prevalence of Dependency, Its Relationship to Total Population, and Dependency Ratios. Bull. World Health Organ. 2004, 82, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Najwyższa Izba Kontroli, P. Dostępność Opieki Długoterminowej Finansowanej Ze Środków Nfz; Najwyższa Izba Kontroli: Warsaw, Poland, 2020; pp. 1–94. Available online: www.nik.gov.pl (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Wong, F.M.F.; Ng, Y.T.Y.; Keung Leung, W. Oral Health and Its Associated Factors among older Institutionalized Residents—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Envion. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.; Pearson, A. Oral Hygiene Care for Residents with Dementia: A Literature Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, J.; Kitagaki, K.; Ueda, Y.; Nishio, E.; Shibatsuji, T.; Uchihashi, Y.; Adachi, R.; Ono, R. Impact of Polypharmacy on Oral Health Status in Elderly Patients Admitted to the Recovery and Rehabilitation Ward. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2021, 21, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbe, A.G. Medication-Induced Xerostomia and Hyposalivation in the Elderly: Culprits, Complications, and Management. Drugs Aging 2018, 35, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Putten, G.J.; de Baat, C.; de Visschere, L.; Schols, J. Poor Oral Health, a Potential New Geriatric Syndrome. Gerodontology 2014, 31, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sifuentes, A.M.F.; Lapane, K.L. Oral Health in nursing homes: What we know and what we need to know. J. Nurs. Home Res. Sci. 2020, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, S.; Sloane, P.D.; Cohen, L.W.; Barrick, A.L. Changing the Culture of Mouth Care: Mouth Care without a Battle. Gerontologist 2014, 54 (Suppl. S1), S25–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Yi, Y.J.; Donnelly, L.R. Oral Health of Older Residents in Care and Community Dwellers: Nursing Implications. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2017, 64, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossioni, A.; Hajto-Bryk, J. An Expert Opinion from the European College of Gerodontology and the European Geriatric Medicine Society: European Policy Recommendations on Oral Health in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, R.; Gondivkar, S.; Gadbail, A.R.; Yuwanati, M.; Gadbail, M.M.; Likhitkar, M.; Sarode, S.; Sarode, G.; Patil, S. Role of Oral Foci in Systemic Diseases: An Update. Int. J. Contemp. Dent. Med. Rev. 2017, 8, 040117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, P.; Polak-Szlósarczyk, P.; Dyduch-Dudek, W.; Zarzecka-Francica, E.; Styrna, M.; Czekaj, Ł.; Zarzecka, J. Oral Health of Elderly People in Institutionalized Care and Three-Month Rehabilitation Programme in Southern Poland: A Case-Control Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods, 5th ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland; Available online: www.who.int (accessed on 4 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Tanasiewicz, M.; Hildebrandt, T.; Obersztyn, I. Xerostomia of Various Etiologies: A Review of the Literature. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2016, 25, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challacombe, S. The Challacombe Scale. Oral Dis. 2011, 17, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat European Union. Ageing Europe—Looking at the Lives of Older People in the EU. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Ageing_Europe_-_looking_at_the_lives_of_older_people_in_the_EU (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- Lin, H.C.; Corbet, E.F.; Lo, E. Oral Mucosal Lesions in Adult Chinese. Think Reason 2001, 7, 121–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.; Cheah, S.B. The Prevalence of Oral Mucosal Lesions in the Elderly in a Surgical Biopsy Population: A Retrospective Analysis of 4042 Cases. Gerodontology 1989, 8, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jainkittivong, A.; Aneksuk, V.; Langlais, R.P. Oral Mucosal Conditions in Elderly Dental Patients. Oral Dis. 2002, 8, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nederfors, T. Xerostomia and Hyposalivation. Adv. Dent. Res. 2000, 14, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mese, H.; Matsuo, R. Salivary Secretion, Taste and Hyposalivation. J. Oral Rehabil. 2007, 34, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.Y.; Chen, J.H.; Du, J.K.; Lin, Y.C.; Ho, P.S.; Lee, C.H.; Hu, C.Y.; Huang, H.L. Dysphagia and Masticatory Performance as a Mediator of the Xerostomia to Quality of Life Relation in the Older Population. BMC Geriatr 2020, 20, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y.; Kim, N.H.; Kho, H.S. Geriatric Oral and Maxillofacial Dysfunctions in the Context of Geriatric Syndrome. Oral Dis. 2018, 24, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lima Saintrain, M.V.; Gonçalves, R.D. Salivary Tests Associated with Elderly People’s Oral Health. Gerodontology 2013, 30, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, M.S.; Castelo, P.M.; Chaves, G.N.; Fernandes, J.P.S.; Fonseca, F.L.A.; Zanato, L.E.; Gavião, M.B.D. Relationship between Polypharmacy, Xerostomia, Gustatory Sensitivity, and Swallowing Complaints in the Elderly: A Multidisciplinary Approach. J. Texture Stud. 2021, 52, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, M.H.; Vissink, A.; Spoorenberg, S.L.; Jager-Wittenaar, H.; Wynia, K.; Visser, A. Are Edentulousness, Oral Health Problems and Poor Health-Related Quality of Life Associated with Malnutrition in Community-Dwelling Elderly (Aged 75 Years and Over)? A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohorst, J.J.; Bruce, A.J.; Torgerson, R.R.; Schenck, L.A.; Davis, M.D. The Prevalence of Burning Mouth Syndrome: A Population—Based Study John. Br. J. Dermatol. 2015, 172, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, S.D. Burning Mouth Syndrome. Dhermatologic. Ther. 2010, 23, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scala, A.; Checchi, L.; Montevecchi, M.; Marini, I.; Giamberardino, M.A. Update on burning mouth sydnrome: Overview and managemen. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. Vol. 2003, 14, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization Technical Report; Medication Safety in Polypharmacy. 2019. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325454/WHO-UHC-SDS-2019.11-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Masnoon, N.; Shakib, S.; Kalisch-Ellett, L.; Caughey, G.E. What Is Polypharmacy? A Systematic Review of Definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navazesh, M.; Brightman, V.J.; Pogoda, J.M. Relationship of Medical Status, Medications, and Salivary Flow Rates in Adults of Different Ages. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 1996, 81, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray Thomson, W.; Chalmers, J.M.; John Spencer, A.; Slade, G.D.; Carter, K.D. A Longitudinal Study of Medication Exposure and Xerostomia among Older People. Gerodontology 2006, 23, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazar, I.; Urek, M.M.; Brumini, G.; Pezelj-Ribaric, S. Oral Sensorial Complaints, Salivary Flow Rate and Mucosal Lesions in the Institutionalized Elderly. J. Oral Rehabil. 2010, 37, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, L.A.; Lin, S.M.; Teixeira, M.J.; de Siqueira, J.T.T.; Jacob Filho, W.; de Siqueira, S.R.D.T. Sensorial Differences According to Sex and Ages. Oral Dis. 2014, 20, e103–e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heft, M.W.; Robinson, M.E. Age Differences in Orofacial Sensory Thresholds. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 1102–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbach, S.; Hundt, W.; Vaitl, A.; Heinrich, P.; Förster, S.; Bürger, K.; Zahnert, T. Taste in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurol. 2010, 257, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashihara, K.; Hanaoka, A.; Imamura, T. Frequency and Characteristics of Taste Impairment in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: Results of a Clinical Interview. Intern. Med. 2011, 50, 2311–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, K.J.; Haryono, R.Y.; Keast, R.S.J. Taste Changes and Saliva Composition in Chronic Kidney Disease. Ren. Soc. Australas. J. 2012, 8, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Musialik, J.; Suchecka, W.; Klimacka-Nawrot, E.; Petelenz, M.; Hartman, M.; Błońska-Fajfrowska, B. Taste and Appetite Disorders of Chronic Hepatitis C Patients. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 24, 1400–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, E.; de Souza, R.F.; Kabawat, M.; Feine, J.S. The Impact of Edentulism on Oral and General Health. Int. J. Dent. 2013, 2013, 498305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolkka-Palomaa, M.; Jääskeläinen, S.K.; Laine, M.A.; Teerijoki-Oksa, T.; Sandell, M.; Forssell, H. Pathophysiology of Primary Burning Mouth Syndrome with Special Focus on Taste Dysfunction: A Review. Oral Dis. 2015, 21, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samnieng, P.; Ueno, M.; Shinada, K.; Zaitsu, T.; Wright, F.A.; Kawaguchi, Y. Association of Hyposalivation with Oral Function, Nutrition and Oral Health in Community-Dwelling Elderly Thai. Community Dent. Health 2016, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, M.; Yamashita, Y. Oral Health and Swallowing Problems. Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Rep. 2013, 1, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kho, H.S. Understanding of Xerostomia and Strategies for the Development of Artificial Saliva. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 17, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.S.; Kim, H.G.; Moreno, K. Xerostomia Among Older Adults With Low Income: Nuisance or Warning? J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2016, 48, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanie, K.-J.; Bird, W.F.; Paul, S.M.; Lewis, L.; Schell, E.S. An Instrument to Assess the Oral Health Status of Nursing Home Residents. Gerontologist 1995, 35, 814–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Oral Cavity Complaints | Study Group | p | φc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMCH | MHCOD | |||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| Pain | 26 (86.7%) | 4 (13.3%) | 43 (86%) | 7 (14%) | 1.000 | 0.01 |

| Bleeding | 28 (93.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | 49 (98%) | 1 (2%) | 0.553 | 0.12 |

| Tooth Mobility | 30 (100%) | 0 | 49 (98%) | 1 (2%) | 1.000 | 0.09 |

| Halitosis | 28 (93.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | 48 (96%) | 2 (4%) | 0.628 | 0.06 |

| Oral burning | 28 (93.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | 50 (100%) | 0 | 0.138 | 0.21 |

| Excess of saliva | 29 (96.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | 49 (98%) | 1 (2%) | 1.000 | 0.04 |

| Dryness | 20 (66.7%) | 10 (33.3%) | 31 (62%) | 19 (38%) | 0.857 | 0.05 |

| Swallowing problems | 28 (93.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | 41 (82%) | 9 (18%) | 0.195 | 0.16 |

| Lack of saliva | 24 (80%) | 6 (20%) | 32 (64%) | 18 (36%) | 0.207 | 0.17 |

| Pain, crackling, skipping in temporomandibular joint (TMJ) | 28 (93.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | 49 (98%) | 1 (2%) | 0.553 | 0.12 |

| Other | 30 (100%) | 0 | 48 (96%) | 2 (4%) | 0.525 | 0.12 |

| Oral Mucosal Complaints | Study Group | p | φc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMCH | MHCOD | |||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| General | 28 (93.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | 48 (96%) | 2 (4%) | 0.628 | 0.06 |

| Decrease in saliva | 17 (56.7%) | 13 (43.3%) | 27 (54%) | 23 (46%) | 1.000 | 0.03 |

| Increase in saliva | 29 (96.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | 48 (96%) | 2 (4%) | 1.000 | 0.02 |

| Taste disorder | 29 (96.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | 46 (92%) | 4 (8%) | 0.645 | 0.09 |

| Mucosal burning | 26 (86.7%) | 4 (13.3%) | 44 (88%) | 6 (12%) | 1.000 | 0.020 |

| Difficulty in taking food | 24 (80%) | 6 (20%) | 37 (74%) | 13 (26%) | 0.598 | 0.07 |

| Problem with performing hygiene procedures | 28 (93.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | 43 (86%) | 7 (14%) | 0.471 | 0.11 |

| Difficulty in using dentures | 26 (86.7%) | 4 (13.3%) | 35 (70%) | 15 (30%) | 0.109 | 0.19 |

| Oral Mucosal Complaints | Lack of Complaints | Presence of Complaints | WMann-Whitney | p | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mdn (IQR) | n | Mdn (IQR) | |||||

| General | 76 | 1.0 (3.25) | 4 | 0.5 (1.5) | 179.0 | 0.540 | −0.38–0.64 | 0.18 |

| Decrease in saliva | 44 | 1.0 (2.25) | 36 | 1.0 (4.0) | 689.5 | 0.300 | −0.37–0.13 | −0.13 |

| Increase in saliva | 77 | 1.0 (3.0) | 3 | 5.0 (3.0) | 79.00 | 0.340 | −0.76–0.33 | −0.32 |

| Taste disorder | 75 | 1.0 (3.0) | 5 | 1.0 (4.0) | 150.5 | 0.450 | −0.62–0.31 | −0.20 |

| Mucosal burning | 70 | 1.0 (2.75) | 10 | 4.0 (4.75) | 208.0 | 0.032 | −0.67–−0.05 | −0.41 |

| Difficulty in taking food | 61 | 1.0 (3.0) | 19 | 1.0 (5.0) | 465.0 | 0.180 | −0.46–0.10 | −0.20 |

| Problem with performing hygiene procedures | 71 | 1.0 (3.0) | 9 | 1.0 (4.0) | 251.0 | 0.280 | −0.55–0.18 | −0.21 |

| Difficulty in using dentures | 61 | 1.0 (3.0) | 19 | 2.0 (4.0) | 360.5 | 0.010 | −0.60–−0.10 | −0.38 |

| Type of Medications | Study Group | p | φc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMCH | MHCOD | |||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| Anticholinergics | 29 (96.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | 46 (92%) | 4 (8%) | 0.645 | 0.09 |

| Antihistamines | 26 (86.7%) | 4 (13.3%) | 47 (94%) | 3 (6%) | 0.416 | 0.13 |

| Antihypertensive | 9 (30%) | 21 (70%) | 14 (28%) | 36 (72%) | 1.000 | 0.02 |

| For Parkinson’s disease | 29 (96.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | 41 (82%) | 9 (18%) | 0.081 | 0.22 |

| Cytotoxic | 29 (96.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | 47 (94%) | 3 (6%) | 1.000 | 0.06 |

| Sedative | 12 (40%) | 18 (60%) | 25 (50%) | 25% (50%) | 0.524 | 0.10 |

| Relaxants | 28 (93.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | 44 (88%) | 6 (12%) | 0.703 | 0.086 |

| Antidepressants | 23 (76.7%) | 7 (23.3%) | 27 (54%) | 23 (46%) | 0.074 | 0.23 |

| Anticoagulants | 21 (70%) | 9 (30%) | 37 (74%) | 13 (26%) | 0.797 | 0.04 |

| Bone resorption inhibitors | 29 (96.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | 48 (96%) | 2 (4%) | 1.000 | 0.02 |

| Other | 6 (20%) | 24 (80%) | 12 (24%) | 38 (76%) | 0.786 | 0.05 |

| Study Group | n | M | SD | Mdn | IQR | Min | Max | Sk. | Kurt. | W | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of medications | DMCH | 30.00 | 6.23 | 3.13 | 6.00 | 3.75 | 0.00 | 13.00 | 0.24 | −0.57 | 0.97 | 0.07 |

| MHCOD | 50.00 | 6.32 | 2.34 | 6.00 | 3.75 | 0.00 | 12.00 | 0.14 | 0.05 |

| Oral Cavity Complaints | No Complaints | Presence of Complaints | tWelch | p | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | |||||

| Pain | 69 | 6.2 (2.35) | 11 | 7.0 (4.12) | −0.65 | 0.530 | −0.92–0.48 | −0.23 |

| Bleeding | 77 | 6.43 (2.59) | 3 | 2.67 (1.15) | 5.16 | 0.016 | 0.18–2.47 | 1.33 |

| Tooth mobility | 79 | 6.25 (2.64) | 1 | 9.00 (0) | - | - | - | - |

| Halitosis | 76 | 6.2 (2.57) | 4 | 8.0 (3.92) | −0.91 | 0.430 | −1.29–0.54 | −0.40 |

| Burning | 78 | 6.29 (2.66) | 2 | 6.0 (2.86) | 0.15 | 0.910 | −0.07–0.08 | 0.01 |

| Excess of saliva | 78 | 6.19 (2.56) | 2 | 10.0 (4.24) | −1.26 | 0.420 | −0.07–0.03 | −0.03 |

| Dryness | 51 | 5.80 (2.47) | 29 | 7.14 (2.76) | −2.16 | 0.036 | −0.97–−0.03 | −0.50 |

| Swallowing problems | 69 | 6.36 (2.57) | 11 | 5.82 (3.19) | 0.54 | 0.600 | −0.47–0.82 | 0.18 |

| Lack of saliva | 56 | 5.77 (2.49) | 24 | 7.50 (2.64) | −2.74 | 0.009 | −1.15–−0.16 | −0.66 |

| Pain, crackling, skipping in TMJ | 77 | 6.14 (2.57) | 3 | 10.0 (1.73) | −3.70 | 0.051 | −2.22–0.01 | −1.12 |

| Other | 78 | 6.27 (2.67) | 2 | 7.00 (1.41) | −0.70 | 0.600 | −0.26–0.14 | −0.07 |

| Oral Mucosal Complaints | No Complaints | Presence of Complaints | tWelch | p | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | |||||

| General | 76 | 6.13 (2.59) | 4 | 9.25 (2.06) | −2.91 | 0.050 | −1.99–0.00 | −1.02 |

| Decrease in saliva | 44 | 5.61 (2.32) | 36 | 7.11 (2.81) | −2.56 | 0.013 | −1.02–−0.12 | −0.57 |

| Increase in saliva | 77 | 6.23 (2.67) | 3 | 7.67 (1.53) | −1.54 | 0.240 | −1.07–0.25 | −0.44 |

| Taste disorder | 75 | 6.09 (2.56) | 5 | 9.20 (2.39) | −2.80 | 0.041 | −1.98–0.04 | −1.04 |

| Mucosal burning | 70 | 6.06 (2.51) | 10 | 7.90 (3.14) | −1.78 | 0.100 | −1.30–0.12 | −0.60 |

| Difficulty in taking food | 61 | 6.10 (2.46) | 19 | 6.89 (3.16) | −1.01 | 0.320 | −0.81–0.27 | −0.27 |

| Problem with performing hygiene procedures | 71 | 6.25 (2.63) | 9 | 6.56 (2.88) | −0.30 | 0.770 | −0.76–0.56 | −0.10 |

| Difficulty in using dentures | 61 | 6.08 (2.72) | 19 | 6.95 (2.34) | −1.35 | 0.19 | −0.82–0.16 | −0.33 |

| Fox’s Questionnaire | Study Group | p | φc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMCH | MHCOD | |||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| 1. Do you experience mouth dryness during the night or upon waking up? | 17 (56.7%) | 13 (43.3%) | 29 (58%) | 21 (42%) | 1.000 | 0.01 |

| 2. Do you experience mouth dryness during the day? | 19 (63.3%) | 11 (36.7%) | 28 (56%) | 22 (44%) | 0.681 | 0.07 |

| 3. Do you keep a glass of water next to your bed? | 19 (63.3%) | 11 (36.7%) | 31 (62%) | 19 (38%) | 1.000 | 0.01 |

| 4. Do you drink fluids while swallowing dry foods? | 17 (56.7%) | 13 (43.3%) | 26 (52%) | 24 (48%) | 0.862 | 0.05 |

| 5. Do you experience mouth dryness during meals? | 18 (60%) | 12 (40%) | 32 (64%) | 18 (36%) | 0.905 | 0.04 |

| 6. Do you experience problems with swallowing foods? | 22 (73.3%) | 8 (26.7%) | 41 (82%) | 9 (18%) | 0.405 | 0.10 |

| 7. Do you use chewing gum on a daily basis to eliminate a feeling of mouth dryness? | 26 (86.7%) | 4 (13.3%) | 47 (94%) | 3 (6%) | 0.416 | 0.13 |

| 8. Do you use hard fruit or mint candies on a daily basis to eliminate a feeling of mouth dryness? | 22 (73.3%) | 8 (26.7%) | 40 (80%) | 10 (20%) | 0.583 | 0.08 |

| 9. Do you perceive the volume of saliva in your mouth as too small/excessive, or do you just not notice it? | 14 (46.7%) | 16 (53.3%) | 24 (48%) | 26 (52%) | 0.817 | 0.05 |

| 10. Do you need to moisten your mouth frequently? | 18 (60%) | 12 (40%) | 33 (66%) | 17 (34%) | 0.764 | 0.06 |

| Challacombe Test | Study Group | p | φc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMHC | MHCOD | |||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| 1. Mirror sticks to buccal mucosa | 15 (50%) | 15 (50%) | 24 (48%) | 26 (52%) | 1.000 | 0.02 |

| 2. Mirror sticks to tongue | 15 (50%) | 15 (50%) | 16 (32%) | 34 (68%) | 0.173 | 0.18 |

| 3. Saliva frothy | 23 (76.7%) | 7 (23.3%) | 40 (80%) | 10 (20%) | 0.781 | 0.04 |

| 4. No saliva pooling in floor of mouth | 11 (36.7%) | 19 (63.3%) | 20 (40%) | 30 (60%) | 0.953 | 0.03 |

| 5. Tongue shows generalised shortened papillae (mild depapillation) | 8 (26.7%) | 22 (73.3%) | 19 (38%) | 31 (62%) | 0.427 | 0.12 |

| 6. Altered gingival structure (i.e., smooth) | 20 (66.7%) | 10 (33.3%) | 17 (34%) | 33 (66%) | 0.009 | 0.32 |

| 7. Glassy appearance of oral mucosa, especially palate | 20 (66.7%) | 10 (33,3%) | 33 (66%) | 17 (34%) | 1.000 | 0.01 |

| 8. Tongue lobulated/fissured | 14 (46.7%) | 16 (53.3%) | 13 (26%) | 37 (74%) | 0.099 | 0.21 |

| 9. Cervical caries (more than 2 teeth) | 28 (93.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | 41 (82%) | 9 (18%) | 0.195 | 0.16 |

| 10. Debris on palate or sticking to teeth | 18 (60%) | 12 (40%) | 38 (76%) | 12 (24%) | 0.141 | 0.17 |

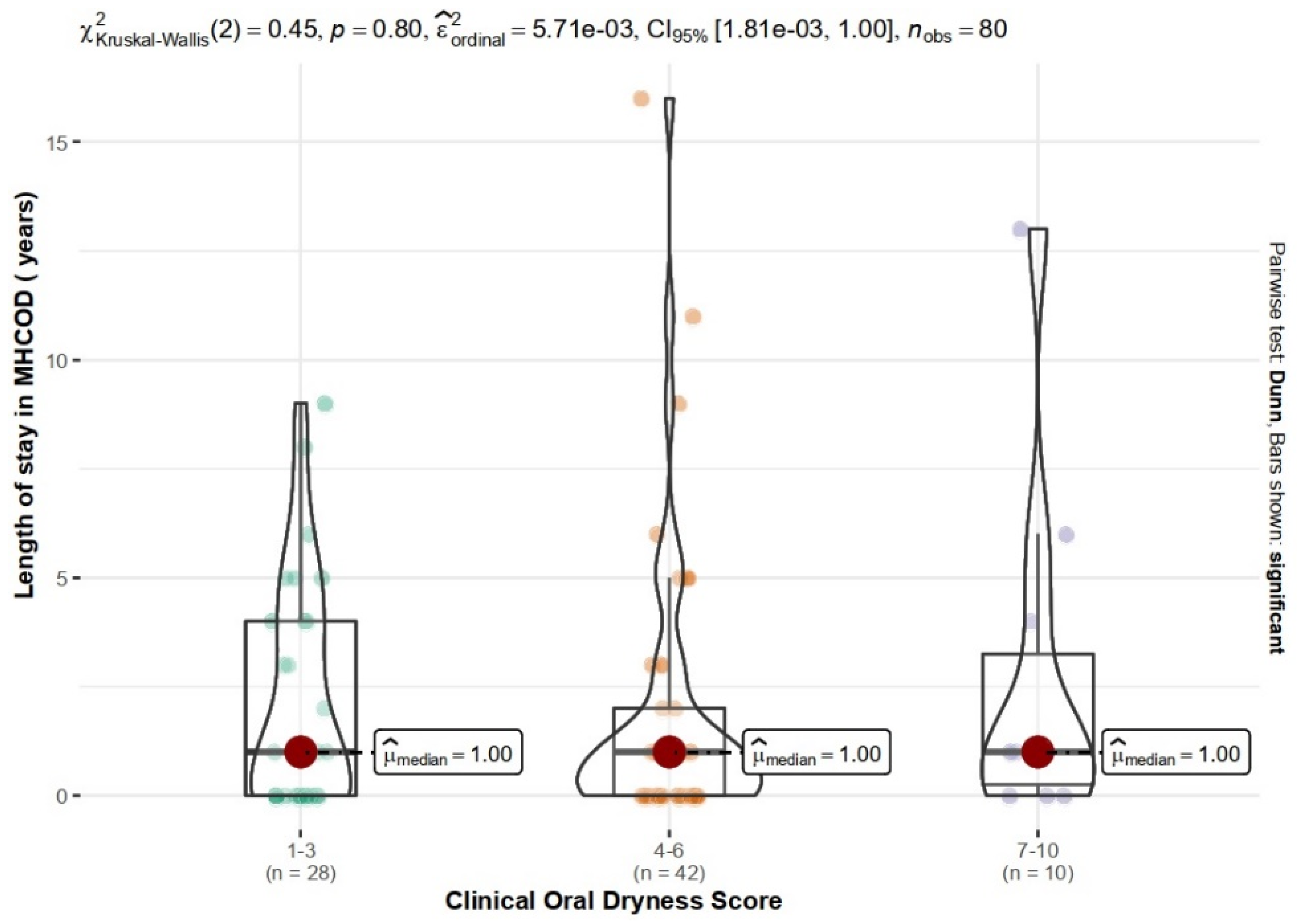

| Study Group | Clinical Oral Dryness Score | df | p | V | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–3 | 4–6 | 7–10 | In Total | ||||

| DMCH | 12 (40%) | 15 (50%) | 3 (10%) | 30 | 2 | 0.755 | 0.09 |

| MHCOD | 16 (32%) | 27 (54%) | 7(14%) | 50 | |||

| In total | 28 (35%) | 42 (52.5%) | 10 (12.5%) | 80 | |||

| Oral Mucosal Complaints | No Complaints | Presence of Complaints | χ2 | V | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n1–3 | n4–6 | n7–10 | n1–3 | n4–6 | n7–10 | ||||

| General | 28 | 39 | 9 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2.41 | 0.17 | 0.240 |

| Decrease in saliva | 18 | 23 | 3 | 10 | 19 | 7 | 3.51 | 0.21 | 0.171 |

| Increase in saliva | 26 | 41 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1.50 | 0.14 | 0.716 |

| Taste disorders | 28 | 38 | 9 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2.88 | 0.19 | 0.253 |

| Mucosal burning | 28 | 34 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 6.16 | 0.28 | 0.026 |

| Difficulty in taking food | 25 | 31 | 5 | 3 | 11 | 5 | 6.57 | 0.29 | 0.037 |

| Problem with performing hygiene procedures | 27 | 37 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 5.19 | 0.26 | 0.059 |

| Difficulty in using dentures | 20 | 33 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 2 | 0.56 | 0.08 | 0.757 |

| Group | Sliding Mirror Test | df | p | V | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Resistance | Slight Resistance | Significant Resistance | In Total | ||||

| DMCH | 13 (43.3%) | 11 (36.7%) | 6 (20%) | 30 | 2 | 0.549 | 0.12 |

| MHCOD | 16 (32%) | 20 (40%) | 14 (28%) | 50 | |||

| In total | 29 (36.2%) | 31 (38.8%) | 20 (25%) | 80 | |||

| Oral Mucosal Complaints | No Complaints | Presence of Complaints | χ2 | V | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nno resistance | nslight resistnace | nsignificant resistance | nno resistance | nslight resistnace | nsignificant resistance | ||||

| General | 29 | 30 | 17 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5.94 | 0.27 | 0.081 |

| Decrease in saliva | 26 | 15 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 17 | 27.55 | 0.59 | <0.001 |

| Increase in saliva | 28 | 31 | 18 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3.38 | 0.21 | 0.175 |

| Taste disorders | 29 | 30 | 16 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 8.87 | 0.33 | 0.019 |

| Mucosal Burning | 28 | 17 | 15 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 5.03 | 0.25 | 0.072 |

| Difficulty in taking food | 25 | 26 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 10.19 | 0.36 | 0.006 |

| Problem with performing hygiene procedures | 27 | 28 | 16 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2.16 | 0.16 | 0.354 |

| Difficulty in using dentures | 25 | 22 | 14 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 2.50 | 0.18 | 0.287 |

| Complaints | No Complaints | Presence of Complaints | χ2 | V | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nno resistance | nslight resistance | nsignifacant resistance | nno resistance | nslight resistance | nsignificant resistance | ||||

| Fox1 | 26 | 15 | 5 | 3 | 16 | 15 | 21.99 | 0.52 | <0.001 |

| Fox2 | 26 | 17 | 4 | 3 | 14 | 16 | 24.02 | 0.55 | <0.001 |

| Fox3 | 26 | 20 | 4 | 3 | 11 | 16 | 24.59 | 0.55 | <0.001 |

| Fox4 | 26 | 14 | 3 | 3 | 17 | 17 | 28.04 | 0.59 | <0.001 |

| Fox5 | 28 | 14 | 8 | 1 | 17 | 12 | 22.64 | 0.53 | <0.001 |

| Fox6 | 27 | 25 | 11 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 10.38 | 0.36 | 0.010 |

| Fox7 | 28 | 29 | 16 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4.40 | 0.23 | 0.144 |

| Fox8 | 28 | 23 | 11 | 1 | 8 | 9 | 12.04 | 0.39 | 0.001 |

| Fox9 | 25 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 20 | 16 | 25.02 | 0.56 | <0.001 |

| Fox10 | 27 | 19 | 5 | 2 | 12 | 15 | 23.89 | 0.55 | <0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Michalak, P.; Polak-Szlósarczyk, P.; Dyduch-Dudek, W.; Kęsek, B.; Zarzecka-Francica, E.; Styrna, M.; Czekaj, Ł.; Zarzecka, J. Oral and Mucosal Complaints among Institutionalized Care Seniors in Malopolska Voivodeship—The Utility of the Mirror Sliding Test in an Assessment of Dry Mouth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13776. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113776

Michalak P, Polak-Szlósarczyk P, Dyduch-Dudek W, Kęsek B, Zarzecka-Francica E, Styrna M, Czekaj Ł, Zarzecka J. Oral and Mucosal Complaints among Institutionalized Care Seniors in Malopolska Voivodeship—The Utility of the Mirror Sliding Test in an Assessment of Dry Mouth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):13776. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113776

Chicago/Turabian StyleMichalak, Piotr, Paulina Polak-Szlósarczyk, Wioletta Dyduch-Dudek, Barbara Kęsek, Elżbieta Zarzecka-Francica, Maria Styrna, Łukasz Czekaj, and Joanna Zarzecka. 2022. "Oral and Mucosal Complaints among Institutionalized Care Seniors in Malopolska Voivodeship—The Utility of the Mirror Sliding Test in an Assessment of Dry Mouth" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 13776. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113776

APA StyleMichalak, P., Polak-Szlósarczyk, P., Dyduch-Dudek, W., Kęsek, B., Zarzecka-Francica, E., Styrna, M., Czekaj, Ł., & Zarzecka, J. (2022). Oral and Mucosal Complaints among Institutionalized Care Seniors in Malopolska Voivodeship—The Utility of the Mirror Sliding Test in an Assessment of Dry Mouth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 13776. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113776