The Impact of Quality of Work Organization on Distress and Absenteeism among Healthcare Workers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Population

2.3. Questionnaire

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Intergroup Comparison

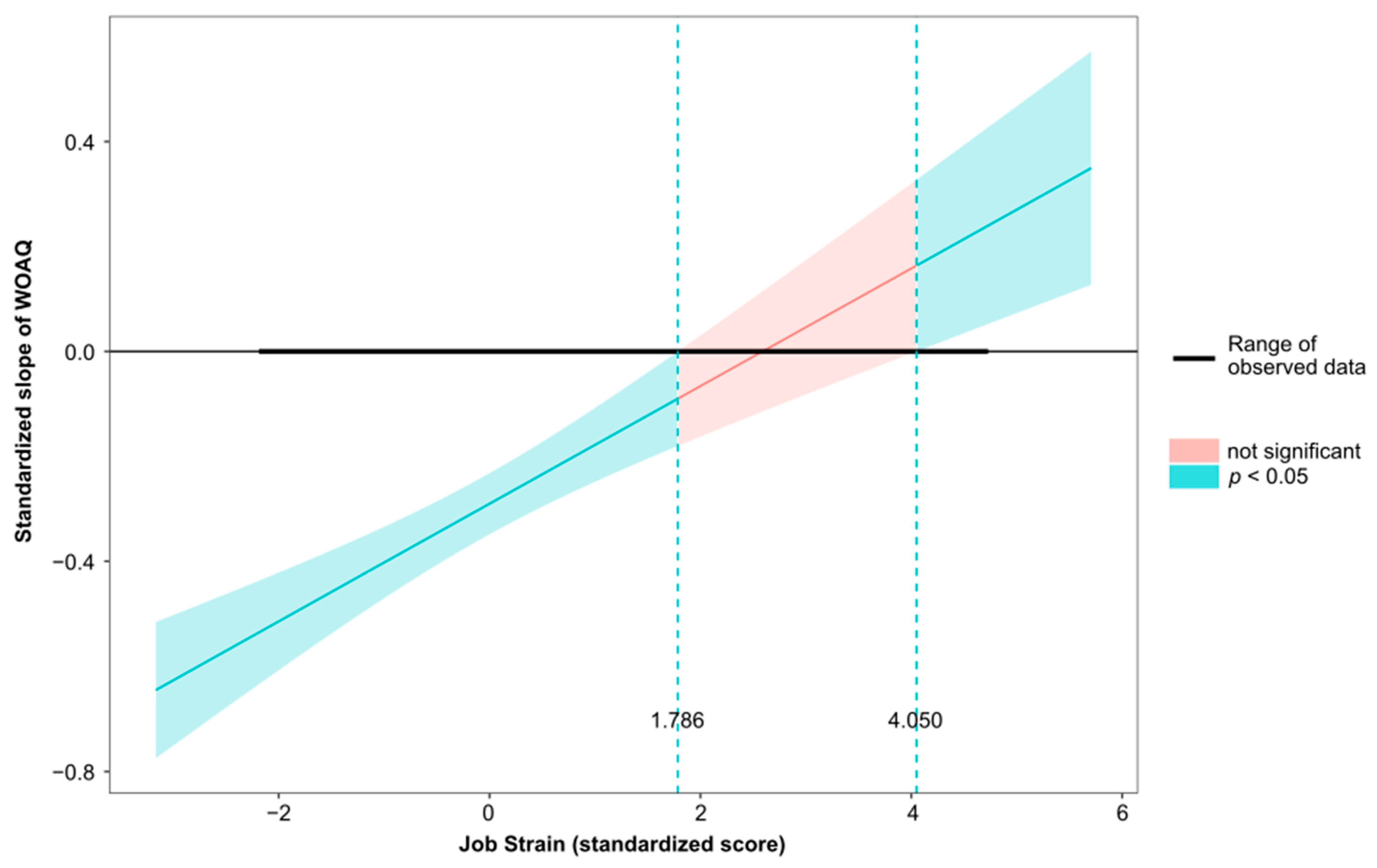

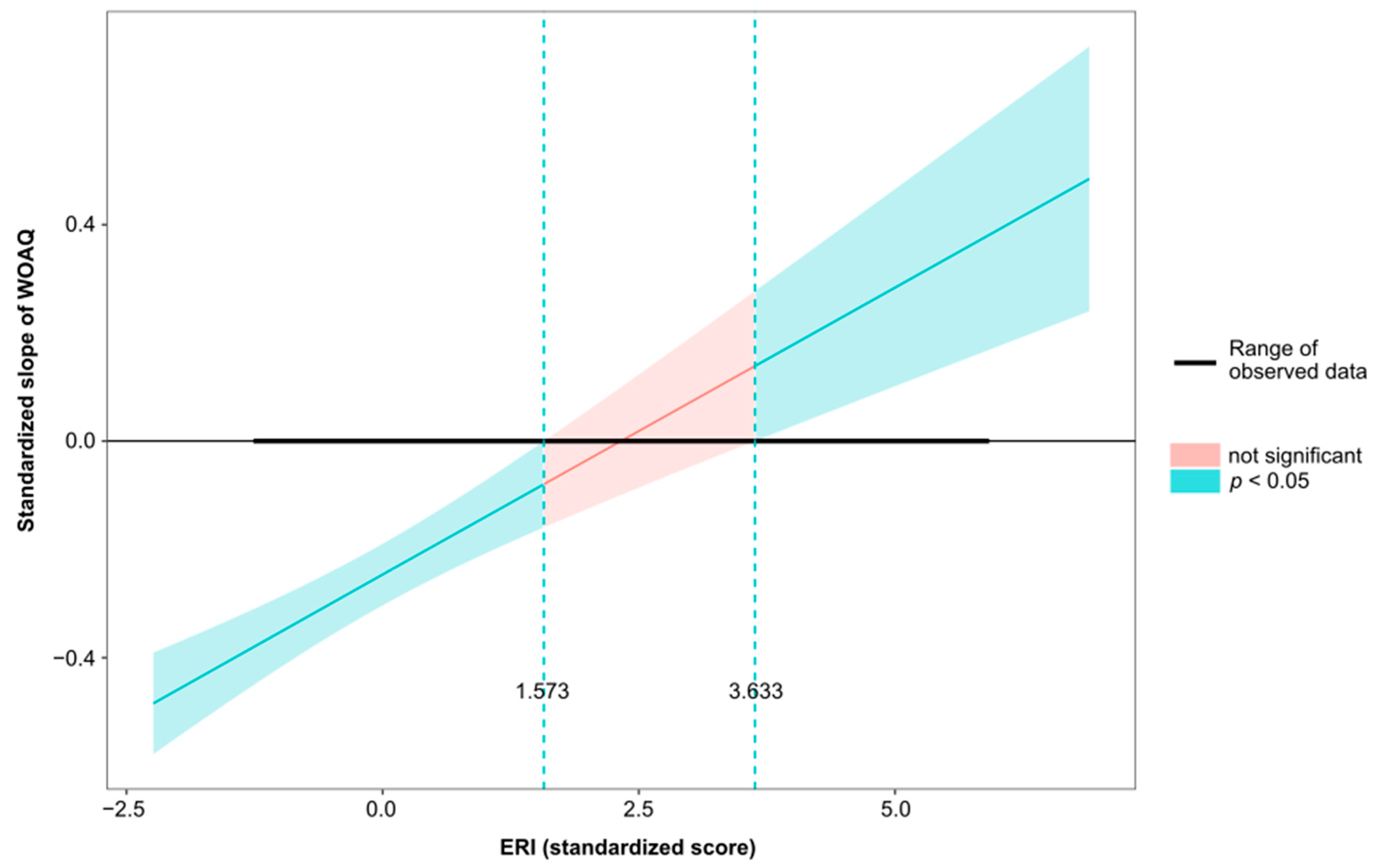

3.2. Relationships between Work Organization, Stress, and Psychological Health

3.3. Relationship between Work Organization and Sickness Absence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Monasta, L.; Abbafati, C.; Logroscino, G.; Remuzzi, G.; Perico, N.; Bikbov, B.; Tamburlini, G.; Beghi, E.; Traini, E.; GBD 2017 Italy Collaborators; et al. Italy’s health performance, 1990–2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e645–e657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odone, A.; Azzopardi-Muscat, N. Health and the effect of universal health coverage in Italy. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e597–e598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettorchi-Tardy, A.; Levif, M.; Michel, M.L.A.P. Benchmarking: A method for continuous quality improvement in health. Healthc. Policy 2012, 7, e101–e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Call, R. ‘Lean’ approach gives greater efficiency. Health Estate 2014, 68, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rotter, T.; Plishka, C.; Lawal, A.; Harrison, L.; Sari, N.; Goodridge, D.; Flynn, R.; Chan, J.; Fiander, M.; Poksinska, B.; et al. What Is Lean Management in Health Care? Development of an Operational Definition for a Cochrane Systematic Review. Eval. Health Prof. 2019, 42, 366–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, G.B.; Da Silveira, G.J.C.; Fogliatto, F.S. Layout Planning in Healthcare Facilities: A Systematic Review. HERD 2019, 12, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.S.; Ahmad, M.N.; Othman, S.H. Business process improvement methods in healthcare: A comparative study. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2019, 32, 887–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozijnsen, L.; Levi, M.; Verkerk, M.J. Why industrial methods do not work in healthcare: An analytical approach. Intern. Med. J. 2020, 50, 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moridzadeh, R.S.; Sanaiha, Y.; Madrigal, J.; Antonios, J.; Benharash, P.; Baril, D.T. Nationwide comparison of the medical complexity of patients by surgical specialty. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 73, 683–688.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, D.A.; Franklin, M.; Child, D.A. Relationship between organizational climate and job satisfaction of nursing personnel. Nurs. Adm. Q. 1990, 14, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.C.; You, C.S.; Tsai, M.T. A multidimensional analysis of ethical climate, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Nurs. Ethics 2012, 19, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marufu, T.C.; Collins, A.; Vargas, L.; Gillespie, L.; Almghairbi, D. Factors influencing retention among hospital nurses: Systematic review. Br. J. Nurs. 2021, 30, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, C.; Schröer, S.; Eilerts, A.L. Evidence of Workplace Interventions-A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lira, C.R.N.; Akutsu, R.C.; Costa, P.R.F.; Leite, L.O.; da Silva, K.B.B.; Botelho, R.B.A.; Raposo, A.; Han, H.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Araya-Castillo, L.; et al. Occupational Risks in Hospitals, Quality of Life, and Quality of Work Life: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taibi, Y.; Metzler, Y.A.; Bellingrath, S.; Müller, A. A systematic overview on the risk effects of psychosocial work characteristics on musculoskeletal disorders, absenteeism, and workplace accidents. Appl. Ergon. 2021, 95, 103434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evanoff, B.A.; Rohlman, D.S.; Strickland, J.R.; Dale, A.M. Influence of work organization and work environment on missed work, productivity, and use of pain medications among construction apprentices. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2020, 63, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, G.; Shao, T.; Xu, Y. Prevalence and associated factors of musculoskeletal disorders among Chinese healthcare professionals working in tertiary hospitals: A cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancman, S.; Barros, J.O.; Jardim, T.A.; Brunoro, C.M.; Sznelwar, L.I.; da Silva, T.N.R. Organisational and relational factors that influence return to work and job retention: The contribution of activity ergonomics. Work 2021, 70, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, K.L.; Irvin, E.; Collie, A.; Clay, F.; Gensby, U.; Jennings, P.A.; Hogg-Johnson, S.; Kristman, V.; Laberge, M.; McKenzie, D.; et al. Effectiveness of Workplace Interventions in Return-to-Work for Musculoskeletal, Pain-Related and Mental Health Conditions: An Update of the Evidence and Messages for Practitioners. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2018, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejeune, J.; Chevalier, S.; Fouquereau, E.; Chenevert, D.; Coillot, H.; Binet, A.; Gillet, N.; Mokounkolo, R.; Michon, J.; Dupont, S.; et al. Relationships Between Managerial and Organizational Practices, Psychological Health at Work, and Quality of Care in Pediatric Oncology. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, e1112–e1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Complete mental health: An agenda for the 21st century. In Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived; Keyes, C.L.M., Haidt, J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 293–312. [Google Scholar]

- Elovainio, M.; Heponiemi, T.; Sinervo, T.; Magnavita, N. Organizational justice and health; review of evidence. G. Ital. Med. Del. Lav. Ergon. 2010, 32, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, M.; Elovainio, M. Justice at the workplace: A review. Camb. Q. Healthc. Ethics 2018, 27, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnavita, N.; Chiorri, C.; Acquadro Maran, D.; Garbarino, S.; Di Prinzio, R.R.; Gasbarri, M.; Matera, C.; Cerrina, A.; Gabriele, M.; Labella, M. Organizational Justice and Health: A Survey in Hospital Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, A.; Cox, T.; Karanika, M.; Khan, S.; Tomás, J.M. Work design and management in the manufacturing sector: Development and validation of the Work Organisation Assessment Questionnaire. Occup. Environ. Med. 2006, 63, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne-Jones, G.; Varnava, A.; Buck, R.; Karanika-Murray, M.; Griffiths, A.; Phillips, C.; Cox, T.; Kahn, S.; Main, C.J. Examination of the Work Organization Assessment Questionnaire in public sector workers. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009, 51, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, L.; Meyer, D. Validity and model-based reliability of the Work Organisation Assessment Questionnaire among nurses. Nurs. Outlook 2015, 63, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, L.; Karanika-Murray, M.; Meyer, D. Cross-Validation of the Work Organization Assessment Questionnaire Across Genders: A Study in the Australian Health Care Sector. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 58, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Karimi, L.; Oakman, J. The Work Organisation Assessment Questionnaire: Validation for use with community nurses and paramedics. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2020, 18, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansfeld, S.; Candy, B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health--a meta-analytic review. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2006, 32, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannizzaro, E.; Ramaci, T.; Cirrincione, L.; Plescia, F. Work-Related Stress, Physio-Pathological Mechanisms, and the Influence of Environmental Genetic Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; Bruinvels, D.; Frings-Dresen, M. Psychosocial work environment and stress-related disorders, a systematic review. Occup. Med. 2010, 60, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhaeghe, R.; Vlerick, P.; Gemmel, P.; Van Maele, G.; De Backer, G. Impact of recurrent changes in the work environment on nurses’ psychological well-being and sickness absence. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 56, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapf, D. Emotion work and psychological well-being: A review of the literature and some conceptual considerations. Hum. Res. Man Rev. 2002, 12, 237–268. [Google Scholar]

- Pugliesi, K. The Consequences of Emotional Labor: Effects on Work Stress, Job Satisfaction, and Well-Being. Motiv. Emot. 1999, 23, 125–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Admin. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostry, A.S.; Kelly, S.; Demers, P.A.; Mustard, C.; Hertzman, C. A comparison between the effort-reward imbalance and demand control models. BMC Public Health 2003, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Lee, J.H.; Gillen, M.; Krause, N. Job stress and work-related musculoskeletal symptoms among intensive care unit nurses: A comparison between job demand-control and effort-reward imbalance models. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2014, 57, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Qayyum, H.; Mason, S. Occupational stress in the ED: A systematic literature review. Emerg. Med. J. 2017, 34, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S.B.; Modini, M.; Joyce, S.; Milligan-Saville, J.S.; Tan, L.; Mykletun, A.; Bryant, R.A.; Christensen, H.; Mitchell, P.B. Can work make you mentally ill? A systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 74, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Ora, C.; Ball, J.; Reinius, M.; Griffiths, P. Burnout in nursing: A theoretical review. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronsson, G.; Theorell, T.; Grape, T.; Hammarström, A.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Träskman-Bendz, L.; Hall, C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- STROBE Checklists. Available online: https://www.strobe-statement.org/checklists/ (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Magnavita, N.; Mammi, F.; Roccia, K.; Vincenti, F. WOA: A questionnaire for the evaluation of work organization. Translation and validation of the Italian version. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2007, 29 (Suppl. 3), 663–665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Magnavita, N. Two tools for health surveillance of job stress: The Karasek Job Content Questionnaire and the Siegrist Effort Reward Imbalance Questionnaire. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2007, 29, 667–670. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karasek, R.; Choi, B.; Ostergren, P.O.; Ferrario, M.; Smet, P.D. Testing two methods to create comparable scale scores between the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) and JCQ-like questionnaires in the European JACE Study. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2007, 14, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theorell, T.; Perski, A.; Åkerstedt, T.; Sigala, F.; Ahlberg-Hultén, G.; Svensson, J.; Eneroth, P. Changes in job strain in relation to changes in physiological state: A longitudinal study. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1988, 14, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.V.; Hall, E.M. Job Strain, Work Place Social Support, and Cardiovascular Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study of a Random Sample of the Swedish Working Population. Am. J. Public Health 1988, 78, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.V.; Hall, E.M.; Theorell, T. Combined Effects of Job Strain and Social Isolation on Cardiovascular Disease Morbidity and Mortality in a Random Sample of the Swedish Male Working Population. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1989, 15, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2011, 52, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J. Psychological resilience, coping behaviours and social support among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of quantitative studies. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1893–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnavita, N.; Garbarino, S.; Siegrist, J. The use of parsimonious questionnaires in occupational health surveillance. Psychometric properties of the short Italian version of the Effort/Reward Imbalance questionnaire. TSWJ Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 372852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Siegrist, J.; Wege, N.; Puhlhofer, F.; Wahrendorf, M. A short generic measure of work stress in the era of globalization: Effortreward imbalance. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2009, 82, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- du Prel, J.B.; Runeson-Broberg, R.; Westerholm, P.; Alfredsson, L.; Fahlén, G.; Knutsson, A.; Nordin, M.; Peter, R. Work overcommitment: Is it a trait or a state? Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2018, 91, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, J.; Li, J. Associations of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Components of Work Stress with Health: A Systematic Review of Evidence on the Effort-Reward Imbalance Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccinelli, M.; Bisoffi, G.; Bon, M.G.; Cunico, L.; Tansella, M. Validity and test-retest reliability of the Italian version of the 12-item General Health Questionnaire in general practice: A comparison between three scoring methods. Compr. Psychiatry 1993, 34, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, P. The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 373–374. [Google Scholar]

- Lumley, T.; Diehr, P.; Emerson, S.; Chen, L. The importance of the normality assumption in large public health data sets. Ann. Rev. Public Health 2002, 23, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PROCESS Vers. 4.1 © 2012–2022 by Andrew F. Hayes. Available online: https://uedufy.com/data-analysis/spss/ (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Ministry of Health. Staff of the National Health Service 2020. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/temi/p2_6.jsp?id=5237&area=statisticheSSN&menu=personaleSSN (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Arakelian, E.; Paulsson, S.; Molin, F.; Svartengren, M. How Human Resources Index, Relational Justice, and Perceived Productivity Change after Reorganization at a Hospital in Sweden That Uses a Structured Support Model for Systematic Work Environment Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Lu, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, B.; Huang, X.; Wan, Q.; Dong, S.; Shang, S. The effects of job characteristics, organizational justice and work engagement on nursing care quality in China: A mediated effects analysis. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollins, A.L.; Eliacin, J.; Russ-Jara, A.L.; Monroe-Devita, M.; Wasmuth, S.; Flanagan, M.E.; Morse, G.A.; Leiter, M.; Salyers, M.P. Organizational conditions that influence work engagement and burnout: A qualitative study of mental health workers. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2021, 44, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sein Myint, N.N.; Kunaviktikul, W.; Akkadechanunt, T.; Wichaikhum, O.A.; Turale, S. Nurses’ Qualitative Descriptions of the Organizational Climate of Hospitals. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2021, 53, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulshof, C.T.; Pega, F.; Neupane, S.; van der Molen, H.F.; Colosio, C.; Daams, J.G.; Descatha, A.; Kc, P.; Kuijer, P.P.; Mandic-Rajcevic, S.; et al. The prevalence of occupational exposure to ergonomic risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Treuer, K.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Little, G. The impact of shift work and organizational work climate on health outcomes in nurses. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pien, L.C.; Cheng, Y.; Cheng, W.J. Psychosocial safety climate, workplace violence and self-rated health: A multi-level study among hospital nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eib, C.; Bernhard-Oettel, C.; Magnusson Hanson, L.L.; Leineweber, C. Organizational justice and health: Studying mental preoccupation with work and social support as mediators for lagged and reversed relationships. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvani, A.; Oksanen, T.; Virtanen, M.; Elovainio, M.; Salo, P.; Pentti, J.; Kivimäki, M.; Vahtera, J. Organizational justice and disability pension from all-causes, depression and musculoskeletal diseases: A Finnish cohort study of public sector employees. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2016, 42, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvani, A.; Oksanen, T.; Virtanen, M.; Salo, P.; Pentti, J.; Kivimäki, M.; Vahtera, J. Clustering of job strain, effort-reward imbalance, and organizational injustice and the risk of work disability: A cohort study. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2018, 44, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, P.; Schablon, A.; Latza, U.; Nienhaus, A. Musculoskeletal pain and effort-reward imbalance—A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, R.M.; Bosch, J.A.; Loerbroks, A.; van Vianen, A.E.; Jarczok, M.N.; Fischer, J.E.; Schmidt, B. Three job stress models and their relationship with musculoskeletal pain in blue- and white-collar workers. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 79, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess-Limerick, R. Participatory ergonomics: Evidence and implementation lessons. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 68, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wåhlin, C.; Stigmar, K.; Nilsing Strid, E. A systematic review of work interventions to promote safe patient handling and movement in the healthcare sector. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, A.M.; Jaegers, L.; Welch, L.; Gardner, B.T.; Buchholz, B.; Weaver, N.; Evanoff, B.A. Evaluation of a participatory ergonomics intervention in small commercial construction firms. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2016, 59, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsen, M.D.; Aust, B.; Kines, P.; Madeleine, P.; Andersen, L.L. Participatory organizational intervention for improved use of assistive devices in patient transfer: A single-blinded cluster randomized controlled trial. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2019, 45, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnavita, N.; Castorina, S.; Ciavarella, M.; Mammi, F.; Roccia, K.; Saffioti, C. Participatory approach to the in-hospital management of musculoskeletal disorders. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2007, 29, 561–563. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Tsai, C.C.; Liu, X.; Wu, Z.; Zeng, X. Effectiveness of participatory ergonomic interventions on musculoskeletal disorders and work ability among young dental professionals: A cluster-randomized controlled trail. J. Occup. Health 2022, 64, e12330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.L.; Boyle, E.; Hartvigsen, J.; Mansell, G.; Søgaard, K.; Jørgensen, M.B.; Holtermann, A.; Rasmussen, C.D.N. Mechanisms for reducing low back pain: A mediation analysis of a multifaceted intervention in workers in elderly care. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2019, 92, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karhula, K.; Turunen, J.; Hakola, T.; Ojajärvi, A.; Puttonen, S.; Ropponen, A.; Kivimäki, M.; Härmä, M. The effects of using participatory working time scheduling software on working hour characteristics and well-being: A quasi-experimental study of irregular shift work. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 112, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnavita, N. Experience of prevention activities in local health units. Assaults and musculoskeletal disorders. Med. Lav. 2009, 100 (Suppl. 1), 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Magnavita, N. Violence prevention in a small-scale psychiatric unit. Program planning and evaluation. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2011, 17, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnavita, N.; Magnavita, G.; Bergamaschi, A. Definition of participatory policy on alcohol and drug in two health care companies. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2010, 4 (Suppl. 2), 300–301. [Google Scholar]

- Magnavita, N. Medical Surveillance, Continuous Health Promotion and a Participatory Intervention in a Small Company. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, S.N.; Broberg, O. Transfer of ergonomics knowledge from participatory simulation events into hospital design projects. Work 2021, 68, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevilacqua, L.; Del Piano, A.; De Matteis, B.; Luciani, E.; Magnavita, L.; Mammi, F.; Presto, M.; Pupp, N.; Roccia, K.; Magnavita, N. The participatory approach to injury prevention appeared to be a useful tool of safety education and ergonomic improvement. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2007, 29, 560–561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saksvik, P.Ø.; Christensen, M.; Tone Innstrand, S.; Vedlog, H.; Indergård, Ø.; Alnes Veldog, H.; Karanika-Murray, M. A six-year effect evaluation of an occupational health intervention—Considering contextual challenges. Am. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 10, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sex | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 115 | 33.3 |

| Female | 230 | 66.7 |

| Category | n | % |

| Physician | 68 | 19.7 |

| Nurse | 201 | 58.3 |

| Support staff | 76 | 22.0 |

| 1-Physician (n = 68) | 2-Nurse (n = 201) | 3-Support Staff (n = 76) | p Value * | |

| Work Organization | 83.7 ± 21.6 | 83.6 ± 20.6 | 81.6 ± 21.7 | 0.769 |

| Demand | 13.5 ± 3.09 | 13.2 ± 3.02 | 13.6 ± 3.22 | 0.518 |

| Control | 17.8 ± 3.23 | 16.6 ± 2.77 | 16.3 ± 3.36 | 0.006 1 vs. 2:0.015 1 vs. 3:0.009 |

| Support | 19.8 ± 3.86 | 19.9 ± 3.29 | 19.3 ± 3.97 | 0.430 |

| Effort | 15.7 ± 5.67 | 15.0 ± 5.05 | 13.4 ± 4.35 | 0.014 1 vs. 3:0.015 |

| Reward | 44.1 ± 9.29 | 42.6 ± 7.59 | 43.0 ± 9.53 | 0.440 |

| Overcommitment | 11.6 ± 5.41 | 11.8 ± 5.14 | 11.1 ± 4.52 | 0.527 |

| Psychological Health | 23.2 ± 5.22 | 23.9 ± 6.14 | 22.1 ± 5.17 | 0.071 |

| Younger (<41 years) (n = 133) | Middle (41–50 years) (n = 126) | Older (>50) (n = 86) | p Value * | |

| Work Organization | 83.7 ± 19.85 | 84.3 ± 21.83 | 80.7 ± 21.63 | 0.450 |

| Demand | 13.5 ± 3.22 | 12.9 ± 2.80 | 13.6 ± 3.20 | 0.138 |

| Control | 16.6 ± 3.11 | 16.7 ± 2.84 | 16.8 ± 3.21 | 0.612 |

| Support | 19.5 ± 3.73 | 20.2 ± 3.30 | 19.4 ± 3.65 | 0.226 |

| Effort | 14.9 ± 5.40 | 14.1 ± 4.38 | 15.5 ± 5.58 | 0.153 |

| Reward | 42.8 ± 8.13 | 43.0 ± 8.75 | 43.3 ± 8.35 | 0.936 |

| Overcommitment | 11.5 ± 5.04 | 11.8 ± 5.16 | 11.5 ± 5.00 | 0.909 |

| Psychological Health | 22.9 ± 5.75 | 23.6 ± 5.83 | 23.8 ± 5.84 | 0.447 |

| Male (n = 115) | Female (n = 230) | p Value ** | ||

| Work Organization | 86.2 ± 22.53 | 81.7 ± 20.12 | 0.061 | |

| Demand | 13.2 ± 3.02 | 13.4 ± 3.11 | 0.562 | |

| Control | 17.1 ± 3.34 | 16.6 ± 2.86 | 0.153 | |

| Support | 19.6 ± 3.88 | 19.8 ± 3.40 | 0.685 | |

| Effort | 14.1 ± 4.85 | 15.1 ± 5.18 | 0.095 | |

| Reward | 44.0 ± 8.99 | 42.5 ± 8.05 | 0.111 | |

| Overcommitment | 10.8 ± 4.92 | 12.0 ± 5.09 | 0.029 | |

| Psychological Health | 22.0 ± 4.32 | 24.1 ± 6.30 | 0.002 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Work Organization | 1 | −0.557 *** | 0.546 *** | −0.563 *** | −0.436 *** | −0.421 *** |

| 2. Job Strain | −0.565 *** | 1 | −0.493 *** | 0.579 *** | 0.370 *** | 0.245 *** |

| 3. Support | 0.551 *** | −0.496 *** | 1 | −0.510 *** | −0.286 *** | −0.165 ** |

| 4. ERI | −0.577 *** | 0.570 *** | −0.525 *** | 1 | 0.570 *** | 0.421 *** |

| 5. Overcommitment | −0.459 *** | 0.377 *** | −0.297 *** | 0.584 *** | 1 | 0.553 |

| 6. Psychological health | −0.436 *** | 0.245 *** | −0.160 ** | 0.423 *** | 0.560 *** | 1 |

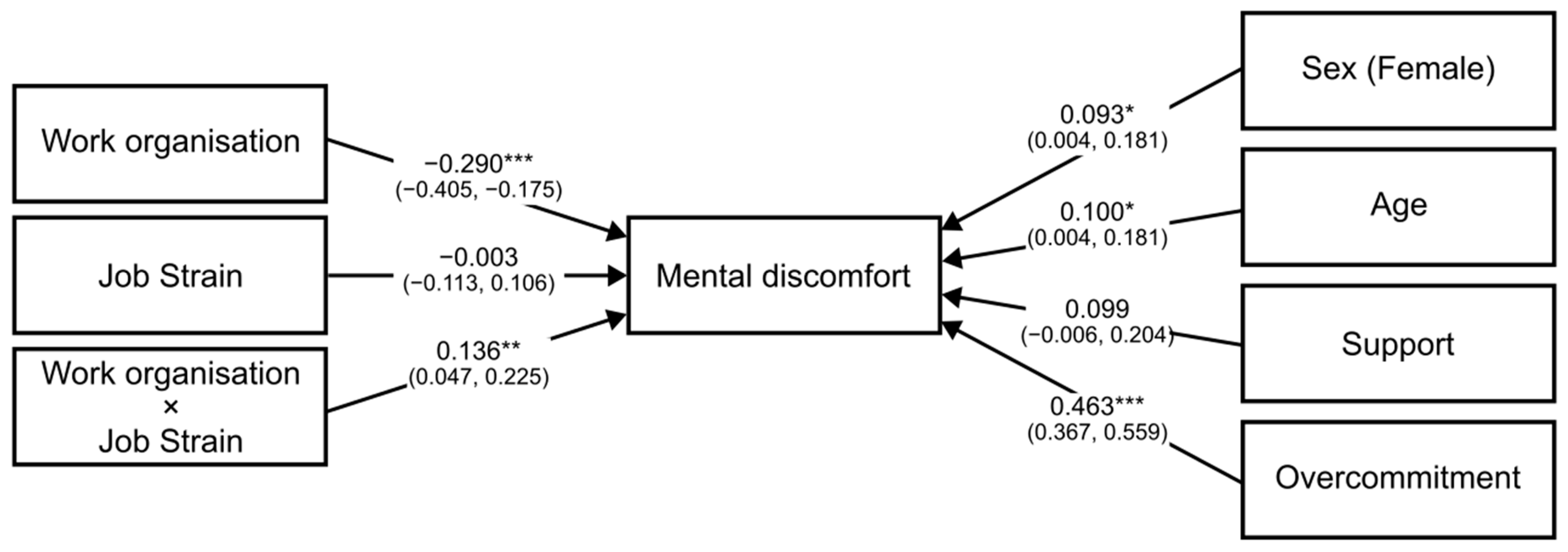

| Measure | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standard Error | t | p Value | Standardized Coefficients | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

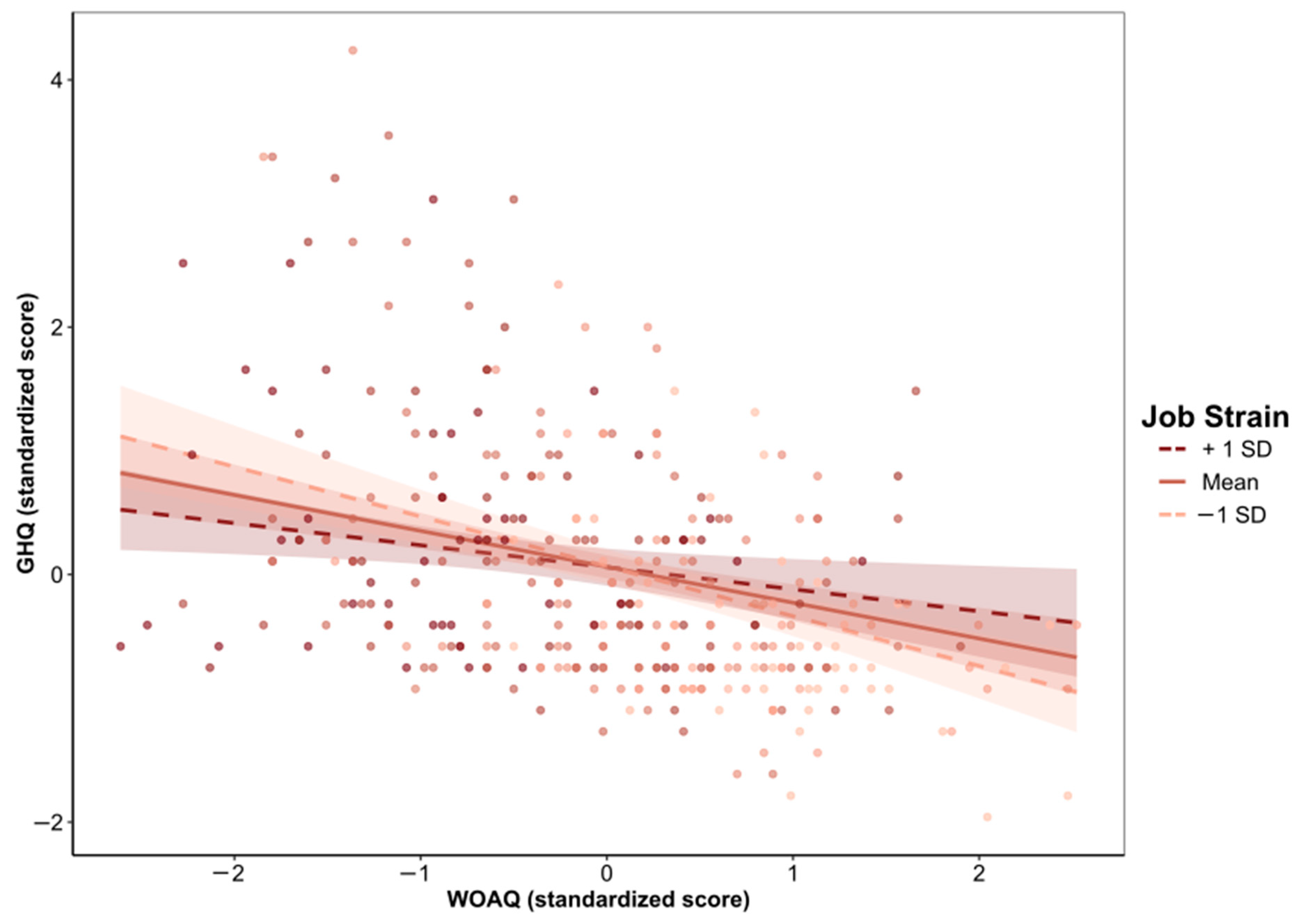

| WOAQ | –0.081 (–0.113, –0.049) | 0.016 | –4.973 | <0.001 | −0.290 (−0.405, −0.175) | 0.240 |

| Job Strain | –0.064 (–2.179, 2.052) | 1.075 | –0.059 | 0.953 | −0.003 (−0.113, 0.106) | 0.000 |

| Interaction WOAQ × Job strain | 0.104 (0.036, 0.172) | 0.035 | 3.009 | 0.003 | 0.136 (0.047, 0.225) | 0.027 |

| Sex (Female) | 1.143 (0.054, 2.233) | 0.554 | 2.065 | 0.040 | 0.093 (0.004, 0.181) | 0.012 |

| Age | 0.067 (0.009, 0.125) | 0.030 | 2.255 | 0.025 | 0.100 (0.013, 0.187) | 0.014 |

| Support | 0.163 (–0.010, 0.335) | 0.088 | 1.857 | 0.064 | 0.099 (−0.006, 0.204) | 0.015 |

| Overcommitment | 0.537 (0.426, 0.648) | 0.057 | 9.512 | <0.001 | 0.463 (0.367, 0.559) | 0.225 |

| R2 | 0.403 |

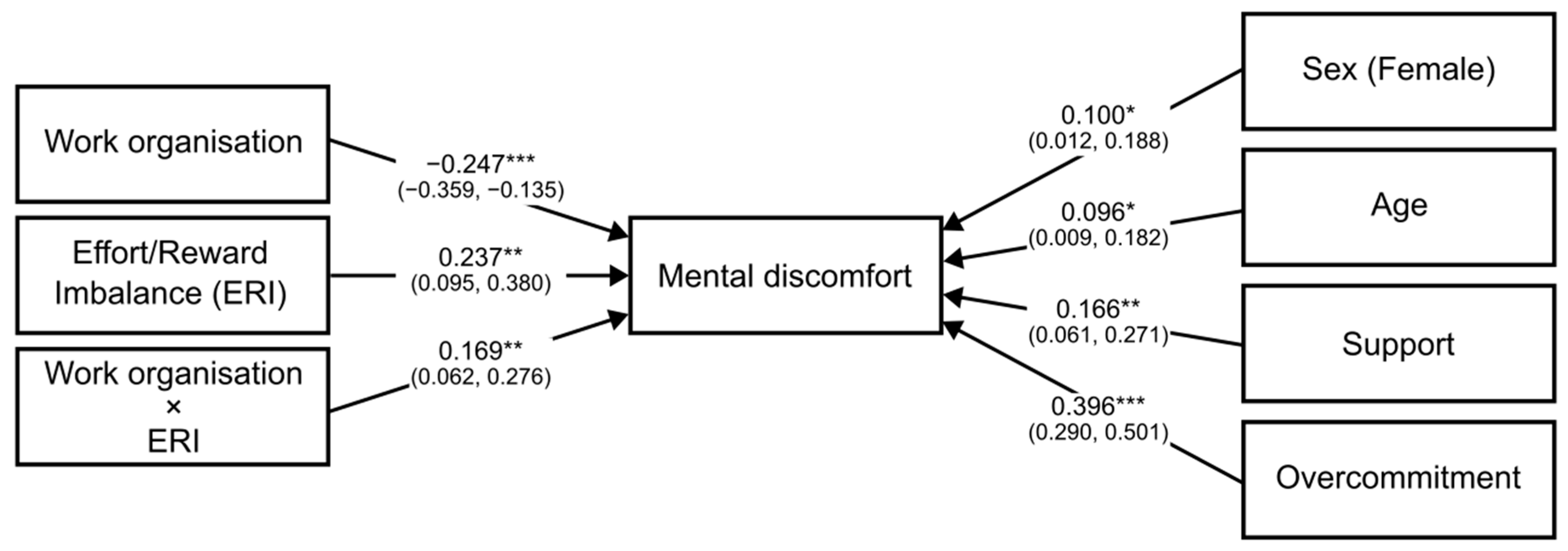

| Measure | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standard Error | t | p Value | Standardized Coefficients | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

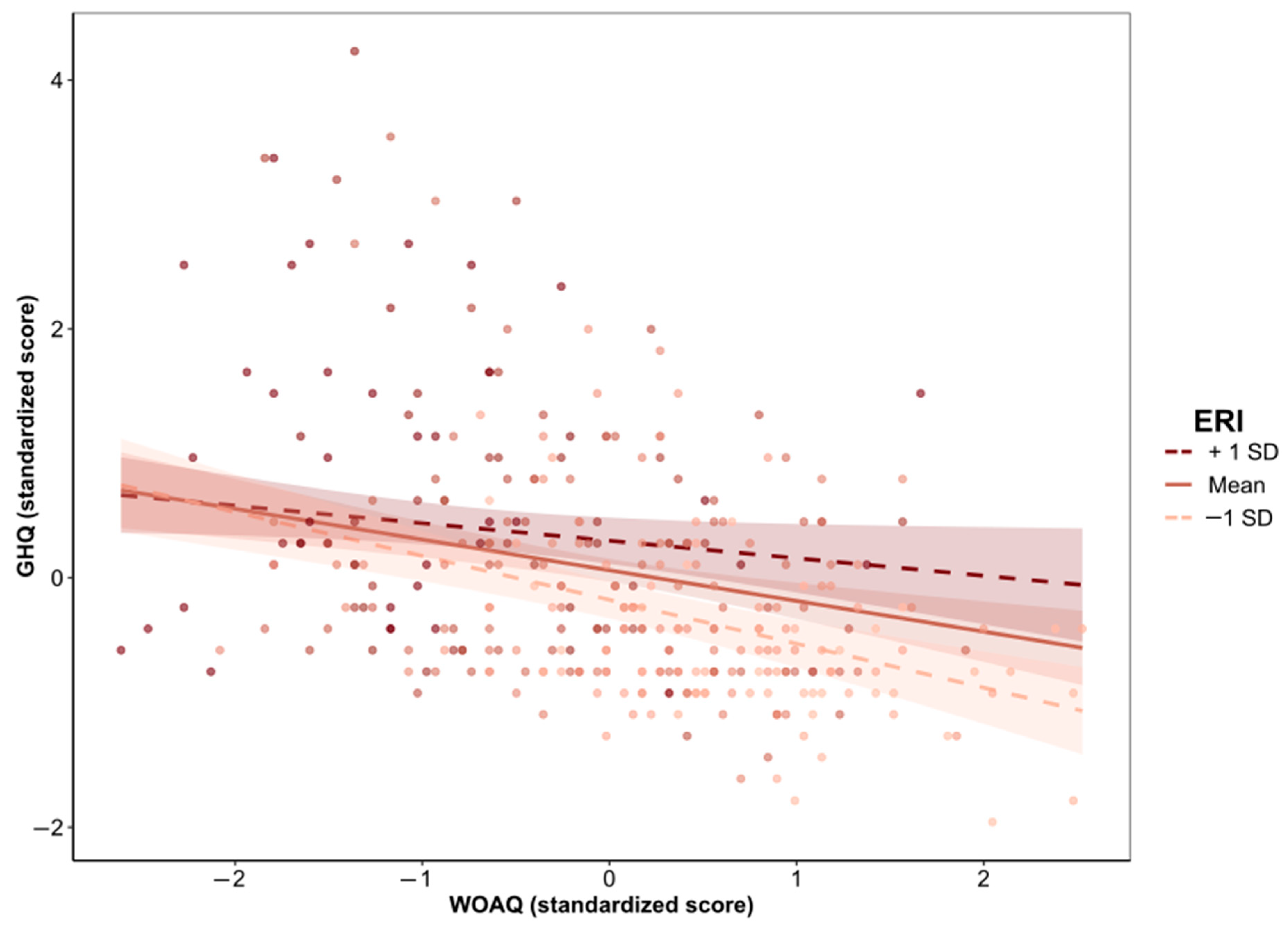

| WOAQ | −0.069 (−0.100, −0.038) | 0.016 | –4.338 | <0.001 | −0.247 (−0.359, −0.135) | 0.241 |

| ERI | 3.609 (1.449, 5.768) | 1.098 | 3.288 | 0.001 | 0.237 (0.095, 0.380) | 0.073 |

| Interaction WOAQ × ERI | 0.077 (0.028, 0.127) | 0.025 | 3.102 | 0.002 | 0.169 (0.062, 0.276) | 0.029 |

| Sex (Female) | 1.231 (0.148, 2.315) | 0.551 | 2.236 | 0.026 | 0.100 (0.012, 0.188) | 0.012 |

| Age | 0.064 (0.006, 0.122) | 0.029 | 2.179 | 0.030 | 0.096 (0.009, 0.182) | 0.015 |

| Support | 0.273 (0.100, 0.447) | 0.088 | 3.097 | 0.002 | 0.166 (0.061, 0.272) | 0.042 |

| Overcommitment | 0.459 (0.337, 0.581) | 0.062 | 7.391 | <0.001 | 0.396 (0.290, 0.501) | 0.163 |

| R2 | 0.409 |

| Variable | Model I (Unadjusted) OR (95% CI) | p Value | Model II (Adjusted) OR (95%CI) | p Value | Nagelkerke R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work Organization | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.003 | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.009 | 0.120 |

| Job Strain | 1.72 (0.79, 3.71) | 0.169 | 1.82 (0.81, 4.11) | 0.149 | 0.102 |

| Social Support | 0.96 (0.90, 1.03) | 0.246 | 0.96 (0.89, 1.02) | 0.198 | 0.100 |

| ERI | 1.63 (0.91, 2.93) | 0.103 | 1.61 (0.87, 2.97) | 0.127 | 0.102 |

| Overcommitment | 1.05 (1.00, 1.10) | 0.048 | 1.94 (0.99, 1.09) | 0.087 | 0.105 |

| Variable | Model I (Unadjusted) OR (95% CI) | p Value | Model II (Adjusted) OR (95%CI) | p Value | Nagelkerke R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work Organization | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | <0.001 | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | <0.001 | 0.074 |

| Job Strain | 1.50 (0.73, 3.08) | 0.096 | 1.51 (0.73, 3.11) | 0.269 | 0.012 |

| Social Support | 0.89 (0.84, 0.95) | 0.001 | 0.89 (0.84, 0.95) | 0.001 | 0.057 |

| ERI | 2.00 (1.10, 3.63) | 0.023 | 2.01 (1.10, 3.67) | 0.023 | 0.028 |

| Overcommitment | 1.02 (0.97, 1,06) | 0.455 | 1.01 (0.97, 1.06) | 0.521 | 0.008 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magnavita, N.; Chiorri, C.; Karimi, L.; Karanika-Murray, M. The Impact of Quality of Work Organization on Distress and Absenteeism among Healthcare Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13458. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013458

Magnavita N, Chiorri C, Karimi L, Karanika-Murray M. The Impact of Quality of Work Organization on Distress and Absenteeism among Healthcare Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13458. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013458

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagnavita, Nicola, Carlo Chiorri, Leila Karimi, and Maria Karanika-Murray. 2022. "The Impact of Quality of Work Organization on Distress and Absenteeism among Healthcare Workers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13458. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013458

APA StyleMagnavita, N., Chiorri, C., Karimi, L., & Karanika-Murray, M. (2022). The Impact of Quality of Work Organization on Distress and Absenteeism among Healthcare Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13458. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013458