Nutritional Status Indicators as Predictors of Postoperative Complications in the Elderly with Gastrointestinal Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

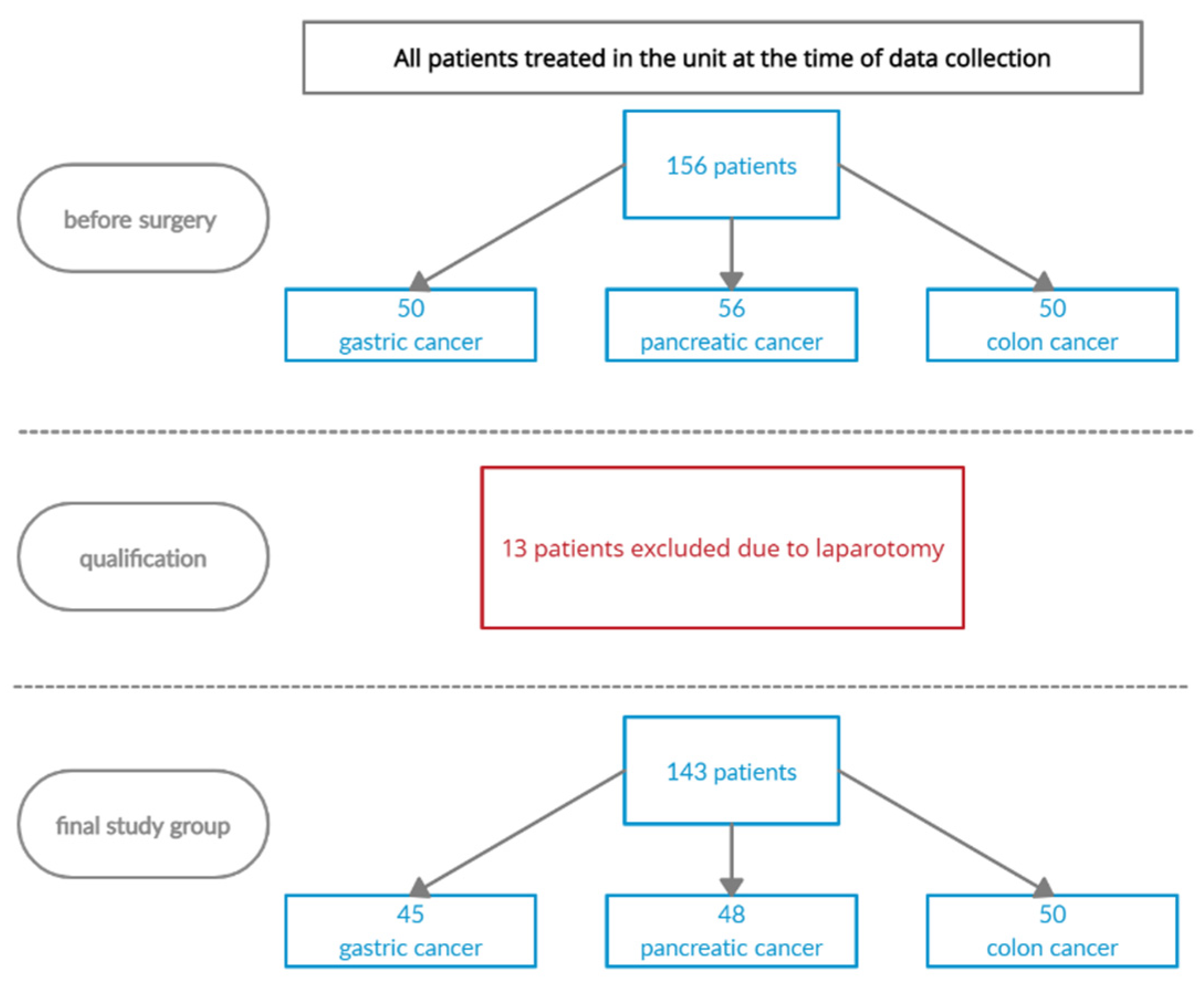

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duron, J.-J.; Duron, E.; Dugue, T.; Pujol, J.; Muscari, F.; Collet, D.; Pessaux, P.; Hay, J.-M. Risk factors for mortality in major digestive surgery in the elderly: A multicenter prospective study. Ann. Surg. 2011, 254, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, E.; Hoogendijk, E.O.; Visvanathan, R.; Wright, O.R.L. Malnutrition Screening and Assessment in Hospitalised Older People: A Review. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2019, 23, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klos, C.L.; Safar, B.; Jamal, N.; Hunt, S.R.; Wise, P.E.; Birnbaum, E.H.; Fleshman, J.W.; Mutch, M.G.; Dharmarajan, S. Obesity increases risk for pouch-related complications following restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA). J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2014, 18, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formiga, F.; Ferrer, A.; Pérez, J.D.U.; Badia, T.; Montero, A.; Soldevila, L.; Moreno, R.; Corbella, X.; The Octabaix Study Group. Detecting malnutrition and predicting mortality in the Spanish oldest old: Utility of the Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score compared with the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) score. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2016, 7, 566–5704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandro-Merhi, V.A.; de Aquino, J.L. Determinants of malnutrition and postoperative complications in hospitalized surgical patients. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2014, 32, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpata, V.; Prendushi, X.; Kreka, M.; Kola, I.; Kurti, F.; Ohri, I. Malnutrition at the time of surgery affects negatively the clinical outcome of critically ill patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Med. Arch. 2014, 68, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.L.; Ong, K.C.; Chan, Y.H.; Loke, W.C.; Ferguson, M.; Daniels, L. Malnutrition and its impact on cost of hospitalization, length of stay, readmission and 3-year mortality. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, P.; Song, Y.; Sun, J.; Chen, X.; Zhao, J.; Ma, B.; Wang, Z. The prognostic nutritional index is a predictive indicator of prognosis and postoperative complications in gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2016, 42, 1176–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adejumo, O.L.; Koelling, T.M.; Hummel, S.L. Nutritional Risk Index predicts mortality in hospitalized advanced heart failure patients. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2015, 34, 1385–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.R.; Yaffee, P.M.; Jamil, L.H.; Lo, S.K.; Nissen, N.; Pandol, S.J.; Tuli, R.; Hendifar, A.E. Pancreatic cancer cachexia: A review of mechanisms and therapeutics. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłęk, S. Wytyczne Europejskiego Towarzystwa Żywienia Klinicznego i Metabolizmu (ESPEN). Adv. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 3, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.D.; Sapra, A. TNM Classification; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk553187 (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- World Medical Association. Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. In Declaration of Helsinki; Version 2013; World Medical Association’s: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Belmont Report. Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. J. Am. Coll Dent. 2014, 81, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cereda, E. Mini nutritional assessment. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2012, 15, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundin, H.; Sääf, M.; Strender, L.E.; Mollasaraie, H.A.; Salminen, H. Mini nutritional assessment and 10-year mortality in free-living elderly women: A prospective cohort study with 10-year follow-up. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 1050–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, D.J.; Shindhe, M.M. Nutritional status assessment of elderly using MNA tool in rural Belagavi: A cross sectional study. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2018, 5, 4799–4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, V.K.G.; Albertini, S.M.; de Moraes, C.M.Z.G.; Godoy, M.; Netinho, J. Malnutrition and clinical outcomes in surgical patients with colorectal disease. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2018, 55, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverkort, E.B.; Binnekade, J.M.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E.; Gouma, D.J.; de Haan, R.J. Estimation of body composition depends on applied device in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2011, 30, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccialanza, R.; Cereda, E.; Klersy, C. Malnutrition, age and inhospital mortality. CMAJ 2011, 183, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.C.; Koh, A.J.H. Nutrition and the elderly surgical patients. MOJ Surg. 2017, 4, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, M.G.; Veronese, G.; Audisio, R.A.; Ugolini, G.; Montroni, I.; de Bock, G.H.; van Leeuwen, B.L.; Vigano, A.; Gilbert, L.; Spiliotis, J.; et al. Poor nutritional status is associated with other geriatric domain impairments and adverse postoperative outcomes in onco-geriatric surgical patients—A multicentre cohort study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 42, 1009–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagoe, R.T.; Goodship, T.H.; Gibson, G.J. The influence of nutritional status on complications after operations for lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2001, 71, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.H.; Cajas-Monson, L.C.; Eisenstein, S.; Parry, L.; Cosman, B. Preoperative malnutrition assessments as predictors of postoperative mortality and morbidity in colorectal cancer: An analysis of ACS-NSQIP. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiya, K.; Kawamura, T.; Omae, K.; Makuuchi, R.; Irino, T.; Tokunaga, M.; Tanizawa, Y.; Bando, E.; Terashima, M. Impact of malnutrition after gastrectomy for gastric cancer on long-term survival. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 25, 974–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donohoe, C.; Ryan, A.; Reynolds, J. Cancer cachexia: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2011, 2011, 601434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardas, M.; Stelmach-Mardas, M.; Zalewski, K. Influence of body weight changes on survival in patients undergoing chemotherapy for epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 1986–1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ohri, P.; Luthra, M.; Negi, K. A study on nutritional status of elderly and its correlates from urban field practice areas of SGRRIM&HS, Dehradun. Indian J. Forensic Community Med. 2018, 5, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, S.; Biswas, A.; Santra, S.; Lahiri, S.K. Assessment of Nutritional Status among Elderly population in a Rural area of West Bengal, India. Int. J. Med. Sci. Public Health 2015, 4, 569–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaid, S.; Bell, T.; Grimm, R.; Ahuja, V. Predicting risk of death in general surgery patients on the basis of preoperative variables using American college of surgeons national surgical quality improvement program data. Perm. J. 2012, 16, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T.; Jensen, G.L.; Correia, M.I.T.D.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Fukushima, R.; Higashiguchi, T.; Baptista, G.; Barazzoni, R.; Blaauw, R.; Coats, A.J.; et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition—A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignini, E.V.; Scarpellini, E.; Rinninella, E.; Lattanzi, E.; Valeri, M.V.; Clementi, N.; Abenavoli, L.; Gasbarrini, A.; Rasetti, C.; Santori, P. Impact of patients nutritional status on major surgery outcome. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 3524–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Lee, D.H.; Jang, J.Y. Effects of Preoperative Malnutrition on Postoperative Surgical Outcomes and Quality of Life of Elderly Patients with Periampullary Neoplasms: A Single-Center Prospective Cohort Study. Gut Liver 2019, 13, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Torre, M.; Ziparo, V.; Nigri, G.; Cavallini, M.; Balducci, G.; Ramacciato, G. Malnutrition and pancreatic surgery: Prevalence and outcomes. J. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 107, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillaud, E.; Liuu, E.; Laurent, M.; Le Thuaut, A.; Vincent, H.; Raynaud-Simon, A.; Bastuji-Garin, S.; Tournigand, C.; Caillet, P.; Canoui-Poitrine, F. Geriatric syndromes increased the nutritional risk in elderly cancer patients independently from tumour site and metastatic status. The ELCAPA-05 cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenring, E.; Elia, M. Which screening method is appropriate for older cancer patients at risk for malnutrition? Nutrition 2015, 31, 594–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walewska, E.; Ścisło, L.; Puto, G.; Krzak, M.; Kłęk, S. Stan odżywienia pacjentów w oddziale chirurgicznym a powikłania pooperacyjne. Postęp. Żyw. Klin. 2019, 2, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, M.; Mazzuoli, S.; Regano, N.; Inguaggiato, R.; Bianco, M.; Leandro, G.; Bugianesi, E.; Noè, D.; Orzes, N.; Pallini, P.; et al. Undernutrition, risk of malnutrition and obesity in gastroenterological patients: A multicenter study. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2016, 8, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ścisło, L.; Walewska, E.; Kłęk, S.; Szczepanik, A.M.; Orzeł-Nowak, A.; Czupryna, A.; Kulig, J. Ocena stanu odżywienia a występowanie powikłań u pacjentów po resekcji żołądka. Probl. Pielęg. 2014, 22, 361–362. [Google Scholar]

- Aaldriks, A.A.; van der Geest, L.G.; Giltay, E.J.; le Cessie, S.; Portielje, J.E.; Tanis, B.C.; Nortier, J.W.; Maartense, E. Frailty and malnutrition predictive of mortality risk in older patients with advanced colorectal cancer receiving chemotherapy. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2013, 4, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischmeyer, P.E.; Carli, F.; Evans, D.; Guilbert, S.; Kozar, R.; Pryor, A.; Thiele, R.H.; Everett, S.; Grocott, M.; Gan, T.J.; et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative Joint Consensus Statement on Nutrition Screening and Therapy Within a Surgical Enhanced Recovery Pathway. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1883–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wightman, S.C.; Posner, M.C.; Patti, M.G.; Ganai, S.; Watson, S.; Prachand, V.; Ferguson, M.K. Extremes of body mass index and postoperative complications after esophagectomy. Dis. Esophagus 2017, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitzman, B.; Schipper, P.H.; Edwards, M.A.; Kim, S.; Ferguson, M.K. Complications after Esophagectomy Are Associated with Extremes of Body Mass Index. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 106, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EuroSurg Collaborative. Body mass index and complications following major gastrointestinal surgery: A prospective, international cohort study and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2018, 20, O215–O225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faes-Petersen, R.; Diaz-Giron-Gidi, A.; Velez-Peres, F.; González-Chávez, M.A.; Lemus, R.; Correa-Rovelo, J.M.; Villegas-Tovar, E. Overweight and obesity as a risk factor for postoperative complications in patients undergoing inguinal hernia repair, cholecystectomy and appendectomy. Rev. Investig. Med. Sur Mex. 2016, 23, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, M.; Miyoshi, N.; Fujino, S. The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index predicts postoperative complications and prognosis in elderly patients with colorectal cancer after curative surgery. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosałka, K.; Wachowska, E.; Słotwiński, R. Disorders of nutritional status in sepsis—Facts and myths. Prz. Gastroenterol. 2017, 12, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbilgin, Ş.; Hancı, V.; Ömür, D.; Özbilgin, M.; Tosun, M.; Yurtlu, S.; Küçükgüçlü, S.; Arkan, A. Morbidity and mortality predictivity of nutritional assessment tools in the postoperative care unit. Medicine 2016, 95, 5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajazi, N.; Mazloom, Z.; Zanad, F.; Rezaianzadeh, A.; Amini, A. Nutritional assessment in critically ill patients. Iran J. Med. Sci. 2016, 41, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Yandell, R.; Fraser, R.J.L.; Chua, A.P.; Chong, M.F.F.; Miller, M. Association between Malnutrition and Clinical Outcomes in the Intensive Care Unit. IPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2017, 41, 744–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, Y.; Gondal, U.; Aziz, O. A systematic review of prehabilitation programs in abdominal cancer surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2017, 39, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimann, A.; Braga, M.; Carli, F.; Higashiguchi, T.; Hübner, M.; Klek, S.; Laviano, A.; Ljungqvist, O.; Lobo, D.N.; Martindale, R.; et al. ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 623–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, C.; Buhler, K.; Bresee, L.; Carli, F.; Gramlich, L.; Culos-Reed, N.; Sajobi, T.; Fenton, T.R. Effects of Nutritional Prehabilitation, with and without Exercise, on Outcomes of Patients Who Undergo Colorectal Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejaz, A.; Spolverato, G.; Kim, Y.; Poultsides, G.A.; Fields, R.C.; Bloomston, M.; Cho, C.S.; Votanopoulos, K.; Maithel, S.K.; Pawlik, T.M. Impact of body mass index on perioperative outcomes and survival after resection for gastric cancer. J. Surg. Res. 2015, 195, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwegler, I.; von Holzen, A.; Gutzwiller, J.P.; Schlumpf, R.; Mühlebach, S.; Stanga, Z. Nutritional risk is a clinical predictor of postoperative mortality and morbidity in surgery for colorectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2010, 97, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amri, R.; Bordeianou, L.G.; Sylla, P.; Berger, D.L. Obesity, Outcomes and Quality of Care: BMI Increases the Risk of Wound-Related Complications in Colon Cancer Surgery. Am. J. Surg. 2014, 207, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, J.; Tatsumi, K.; Ota, M.; Suwa, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Watanabe, A.; Ishibe, A.; Watanabe, K.; Akiyama, H.; Ichikawa, Y.; et al. The impact of visceral obesity on surgical outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for colon cancer. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2014, 29, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermair, A.; Simunovic, M.; Isenring, L.; Janda, M. Nutrition interventions in patients with gynecological cancers requiring surgery. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 145, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.K.; Wang, M.L. The management of perioperative nutrition in patients with end stage liver disease undergoing liver transplantation. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2015, 4, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Fearon, K.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questionnaire/Indicator | n = 143 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric Cancer n = 45 (31%) | Pancreatic Cancer n = 48 (34%) | Colorectal Cancer n = 50 (35%) | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| MNA | Proper nutritional status | 15 (33.3) | 14 (29.2) | 23 (46.0) | 0.10 |

| The risk of malnutrition | 22 (48.9) | 30 (62.5) | 25 (50.0) | ||

| Malnutrition | 8 (17.8) | 4 (8.3) | 2 (4.0) | ||

| BMI | Underweight | 2 (4.4) | 5 (10.4) | 2 (4.0) | 0.52 |

| Standard | 21 (46.7) | 26 (54.2) | 27 (54.0) | ||

| Overweight | 15 (33.3) | 9 (18.8) | 16 (32.0) | ||

| I class obesity | 7 (15.6) | 7 (14.6) | 5 (10.0) | ||

| II class obesity | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Gastric Cancer Patients n = 45 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palliative Surgery | Resection Surgery | |||||||||

| Questionnaire/ Indicator | No complications n = 6 (13.3%) | Occurrence of Complications n = 3 (6.7%) | p | No Complications n = 20 (44.4%) | Occurrence of Complications n = 16 (35.6%) | p | ||||

| MNA | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Normal nutritional status | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.57 | 9 | 64.3 | 5 | 35.7 | 0.38 |

| Risk of malnutrition | 2 | 50.0 | 2 | 50.0 | 10 | 55.7 | 8 | 44.0 | ||

| Malnutrition | 3 | 75.0 | 1 | 25.0 | 1 | 25.0 | 3 | 75.0 | ||

| BMI | ||||||||||

| Underweight | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0.14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 |

| Standard | 4 | 80.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 9 | 56.3 | 7 | 43.8 | ||

| Overweight | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100.0 | 5 | 38.5 | 8 | 61.5 | ||

| I class obesity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 85.7 | 1 | 14.3 | ||

| II class obesity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Pancreatic Cancer Patients n = 48 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palliative Surgery | Resection Surgery | |||||||||

| Questionnaire/ Indicator | No Complications n = 14 (29.2%) | Occurrence of Complications n = 6 (12.5%) | p | No Complications n = 17 (35.4%) | Occurrence of Complications n = 11 (22.9%) | p | ||||

| MNA | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Normal nutritional status | 3 | 100.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.24 | 7 | 63.6 | 4 | 36.4 | 0.93 |

| Risk of malnutrition | 9 | 60.0 | 6 | 40.0 | 9 | 60.0 | 6 | 40.0 | ||

| Malnutrition | 2 | 100.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | ||

| BMI | ||||||||||

| Underweight | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 | 0.82 | 2 | 100.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.49 |

| Standard | 7 | 63.6 | 4 | 36.4 | 10 | 66.7 | 5 | 33.3 | ||

| Overweight | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 | 2 | 33.3 | 4 | 66.7 | ||

| I class obesity | 2 | 100.0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 60.0 | 2 | 40.0 | ||

| II class obesity | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Colorectal Cancer Patients n = 50 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palliative Surgery | Resection Surgery | |||||||||

| No Complications n = 3 (6.0%) | Occurrence of Complications n = 2 (4.0%) | p | No Complications n = 33 (66.0%) | Occurrence of Complications n = 12 (24.0%) | p | |||||

| MNA | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Normal nutritional status | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.93 | 14 | 66.7 | 7 | 33.3 | 0.40 |

| Risk of malnutrition | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 | 18 | 81.8 | 4 | 18.2 | ||

| Malnutrition | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | ||

| BMI | ||||||||||

| Underweight | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.40 | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.29 |

| Standard | 2 | 100.0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 84.0 | 4 | 16.0 | ||

| Overweight | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 9 | 64.3 | 5 | 35.7 | ||

| I class obesity | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100.0 | 2 | 50.0 | 2 | 50.0 | ||

| II class obesity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Gastric Cancer | Colorectal Cancer | Pancreatic Cancer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | p | M | SD | p | M | SD | p | |

| MNA | |||||||||

| Proper nutritional status | 9.7 | 8.2 | 0.15 | 8.8 | 4.6 | 0.39 | 10.8 | 7.3 | 0.18 |

| Risk of malnutrition | 14.3 | 16.2 | 8.7 | 5.0 | 7.6 | 4.8 | |||

| Malnutrition | 9.3 | 7.5 | 8.5 | 4.7 | 5.5 | 0.7 | |||

| BMI | |||||||||

| Underweight | 6.5 | 2.1 | 0.74 | 8.8 | 4.4 | 0.86 | 5.5 | 0.7 | 0.16 |

| Standard | 9.3 | 5.8 | 8.6 | 5.2 | 7.7 | 4.8 | |||

| Overweight | 14.7 | 17.0 | 9.2 | 5.5 | 9.6 | 5.3 | |||

| I class obesity | 15.4 | 18.3 | 9.3 | 3.4 | 15.4 | 11.8 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ścisło, L.; Bodys-Cupak, I.; Walewska, E.; Kózka, M. Nutritional Status Indicators as Predictors of Postoperative Complications in the Elderly with Gastrointestinal Cancer. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013453

Ścisło L, Bodys-Cupak I, Walewska E, Kózka M. Nutritional Status Indicators as Predictors of Postoperative Complications in the Elderly with Gastrointestinal Cancer. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013453

Chicago/Turabian StyleŚcisło, Lucyna, Iwona Bodys-Cupak, Elżbieta Walewska, and Maria Kózka. 2022. "Nutritional Status Indicators as Predictors of Postoperative Complications in the Elderly with Gastrointestinal Cancer" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013453

APA StyleŚcisło, L., Bodys-Cupak, I., Walewska, E., & Kózka, M. (2022). Nutritional Status Indicators as Predictors of Postoperative Complications in the Elderly with Gastrointestinal Cancer. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013453