Stayin’ Alive in Little 5: Application of Sentiment Analysis to Investigate Emotions of Service Industry Workers Responding to Drug Overdoses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Parent Study

2.2. Cleaning

2.3. Sentiment Analysis

2.4. Thematic Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Individuals Have a Part to Play in Addressing the Opioid Epidemic

4.2. Communities Have Many Needs

4.3. Structural Forces Create Pathways and Barriers to Opioid Overdose Response and Rescue

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scholl, L.; Seth, P.; Kariisa, M.; Wilson, N.; Baldwin, G. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths—United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattson, C.L.; Tanz, L.J.; Quinn, K.; Kariisa, M.; Patel, P.; Davis, N.L. Trends and Geographic Patterns in Drug and Synthetic Opioid Overdose Deaths—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER). Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Health Statistics. 2020. Available online: http://wonder.cdc.gov (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Gorgia Department of Public Health. Opioid and Substance Misuse Re-Sponse. 2021. Available online: https://dph.georgia.gov/stopopioidaddiction (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Dowell, D.; Noonan, R.K.; Houry, D. Underlying Factors in Drug Overdose Deaths. JAMA 2017, 318, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, L.; Elliott, J.; Beasley, L.; Oranu, E.; Roth, K.; Nguyễn, J. Naloxone Availability in Independent Community Pharmacies in Georgia, 2019. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2021, 16, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gertner, A.K.; Domino, M.E.; Davis, C.S. Do Naloxone Access Laws Increase Outpatient Naloxone Prescriptions? Evidence from Medicaid. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 190, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.C.; Davis, C.; Xuan, Z.; Walley, A.Y.; Bratberg, J. Laws Mandating Coprescription of Naloxone and Their Impact on Naloxone Prescription in Five US States, 2014–2018. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Pradhan, A.; Ogando, Y.M.; Shaya, F. Impact of the Naloxone Standing Order on Trends in Opioid Fatal Overdose: An Ecological Analysis. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2022, 48, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgia Pharmacy Foundation (n.d.). Opioid Safety Champions! Available online: http://www.gpha.org/champion-bios/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Febres-Cordero, S.; Sherman, A.D.F.; Karg, J.; Kelly, U.; Thompson, L.M.; Smith, K. Designing a Graphic Novel: Engaging Community, Arts, and Culture Into Public Health Initiatives. Health Promot. Pract. 2021, 22, 35S–43S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfson-Stofko, B.; Bennett, A.S.; Elliott, L.; Curtis, R. Drug Use in Business Bathrooms: An Exploratory Study of Manager Encounters in New York City. Int. J. Drug Policy 2017, 39, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, B.; Sisson, L.; Dolatshahi, J.; Blachman-Forshay, J.; Hurley, A.; Paone, D. Delivering Opioid Overdose Prevention in Bars and Nightclubs: A Public Awareness Pilot in New York City. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2020, 26, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohnert, A.S.B.; Tracy, M.; Galea, S. Circumstances and Witness Characteristics Associated With Overdose Fatality. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2009, 54, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, W.M. Goodthinking: A Guide to Qualitative Research; Admap: Oxford, UK, 1999; ISBN 978-1-84116-030-6. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q.; Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-7619-1971-1. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in Qualitative Research: Exploring Its Conceptualization and Operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chivers, B.R.; Garad, R.M.; Boyle, J.A.; Skouteris, H.; Teede, H.J.; Harrison, C.L. Perinatal Distress During COVID-19: Thematic Analysis of an Online Parenting Forum. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K.; Turpeinen, S.; Kvist, T.; Ryden-Kortelainen, M.; Nelimarkka, S.; Enshaeifar, S.; Faithfull, S.; INEXCA Consortium. Experience of Ambulatory Cancer Care: Understanding Patients’ Perspectives of Quality Using Sentiment Analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2021, 44, E331–E338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.J.; Mac, V.V.T.; Hertzberg, V.S. Using Twitter for Nursing Research: A Tweet Analysis on Heat Illness and Health. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2021, 53, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, H. Text Mining Of Twitter Data Using A Latent Dirichlet Allocation Topic Model And Sentiment Analysis. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Eng. 2018, 12, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinerer, I.; Hornik, K.; Meyer, D. Text Mining Infrastructure in R. J. Stat. Soft. 2008, 25, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jockers, M. Syuzhet: Extract Sentiment and Plot Arcs from Text. 2015. Available online: https://https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/syuzhet/syuzhet.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Febres-Cordero, S. Staying Alive in Little Five: Perceptions of Service Industry Workers Who Encounter and Respond to an Opioid Overdose in Little Five Points, Atlanta. Doctoral Dissertation, Laney Graduate School, Druid Hills, GA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://etd.library.emory.edu/concern/etds/w0892c092?locale=en (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Schneider, K.E.; Park, J.N.; Allen, S.T.; Weir, B.W.; Sherman, S.G. Knowledge of Good Samaritan Laws and Beliefs About Arrests Among Persons Who Inject Drugs a Year After Policy Change in Baltimore, Maryland. Public Health Rep. 2020, 135, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, 1st ed.; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-0-671-62244-2. [Google Scholar]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J. Stigma Power. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 103, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurencin, C.T.; Walker, J.M. Racial Profiling Is a Public Health and Health Disparities Issue. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2020, 7, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Atlanta Harm Reduction Coalition. Syringe Service Program: A Free and Confidential Exchange Program. 2021. Available online: https://atlantaharmreduction.org/programs-services/syringe-exchange/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Bardwell, G.; Boyd, J.; Arredondo, J.; McNeil, R.; Kerr, T. Trusting the Source: The Potential Role of Drug Dealers in Reducing Drug-Related Harms via Drug Checking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 198, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.H.; Wong, L.Y.; Grivel, M.M.; Hasin, D.S. Stigma and Substance Use Disorders: An International Phenomenon. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2017, 30, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rego, X.; Oliveira, M.J.; Lameira, C.; Cruz, O.S. 20 Years of Portuguese Drug Policy—Developments, Challenges and the Quest for Human Rights. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2021, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, A.; Munro, A.; Taylor, A. “Once I’d Done It Once It Was like Writing Your Name”: Lived Experience of Take-Home Naloxone Administration by People Who Inject Drugs. Int. J. Drug Policy 2018, 58, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, K.D.; Davidson, P.J.; Iverson, E.; Washburn, R.; Burke, E.; Kral, A.H.; McNeeley, M.; Bloom, J.J.; Lankenau, S.E. “I Felt like a Superhero”: The Experience of Responding to Drug Overdose among Individuals Trained in Overdose Prevention. Int. J. Drug Policy 2014, 25, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.E. (Ed.) Social Stigma: The Psychology of Marked Relationships; W.H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-7167-1591-7. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A. “Perfect Storm:” An Opioid Menace Like Never Before. Georgia Public Broadcast News, 12 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.N.; Rashidi, E.; Foti, K.; Zoorob, M.; Sherman, S.; Alexander, G.C. Fentanyl and Fentanyl Analogs in the Illicit Stimulant Supply: Results from U.S. Drug Seizure Data, 2011–2016. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 218, 108416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.A.; Bohnert, A.S.B.; Blow, F.C.; Gordon, A.J.; Ignacio, R.V.; Kim, H.M.; Ilgen, M.A. Polysubstance Use and Association with Opioid Use Disorder Treatment in the US Veterans Health Administration. Addiction 2021, 116, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartel, R. The Highs and Lows of Little Five: A History of Little Five Points; The History Press: Charleston, SC, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-59629-874-3. [Google Scholar]

- City-Data.Com (n.d.). Little Five Points: Atlanta’s Alternative Neighborhood. Available online: http://www.city-data.com/articles/little-five-points-atlantas-alternative.html#ixzz1g5qvlv6l (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Kueppers, C. Little Five Points Had to Fight to Survive. WABE News Outlet. 2019. Available online: https://www.wabe.org/little-five-points-had-to-fight-to-survive/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Openings And Labor Turnover. January 2019. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/jolts_03152019.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Galambos, N.L.; Fang, S.; Krahn, H.J.; Johnson, M.D.; Lachman, M.E. Up, Not down: The Age Curve in Happiness from Early Adulthood to Midlife in Two Longitudinal Studies. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 1664–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgia Drug and Narcotics Agency. Govenor Deal Signs Naloxone Bill into Law-Expanding Access to an Emergency Tool to Parents to Help Fight the Opioid Epidemic. 2017. Available online: https://gdna.georgia.gov/press-releases/2017-06-26/governor-deal-signs-naloxone-bill-law-expanding-access-emergency-tool#:~:text=naloxone%20does%20not%20produce%20a,To%20someone%20experiencing%20an%20overdose (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Jakubowski, A.; Kunins, H.V.; Huxley-Reicher, Z.; Siegler, A. Knowledge of the 911 Good Samaritan Law and 911-Calling Behavior of Overdose Witnesses. Subst. Abus. 2018, 39, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, R.E.; Kinsman, J.; Crowe, R.P.; Rivard, M.K.; Faul, M.; Panchal, A.R. Naloxone Administration Frequency During Emergency Medical Service Events—United States, 2012–2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulec, N.; Lahey, J.; Suozzi, J.C.; Sholl, M.; MacLean, C.D.; Wolfson, D.L. Basic and Advanced EMS Providers Are Equally Effective in Naloxone Administration for Opioid Overdose in Northern New England. Prehospital Emerg. Care 2018, 22, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mell, H.K.; Mumma, S.N.; Hiestand, B.; Carr, B.G.; Holland, T.; Stopyra, J. Emergency Medical Services Response Times in Rural, Suburban, and Urban Areas. JAMA Surg. 2017, 152, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimbar, L.; Moleta, Y. Naloxone Effectiveness: A Systematic Review. J. Addict. Nurs. 2018, 29, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.C.; Heimer, R.; Grau, L.E. Distinguishing Signs of Opioid Overdose and Indication for Naloxone: An Evaluation of Six Overdose Training and Naloxone Distribution Programs in the United States. Addiction 2008, 103, 979–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordant Health Solutions. The History of Naloxone. 2017. Available online: https://cordantsolutions.com/the-history-of-naloxone/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Jack, M. A Little Bit Higher. In The Great Speckled Bird; Georgia State University, Digital Collections: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1971; Volume 4, p. 18. Available online: https://digitalcollections.library.gsu.edu/digital/collection/GSB/id/2686 (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Link, B.G.; Struening, E.L.; Neese-Todd, S.; Asmussen, S.; Phelan, J.C. Stigma as a Barrier to Recovery: The Consequences of Stigma for the Self-Esteem of People With Mental Illnesses. Psychiatr. Serv. 2001, 52, 1621–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G. Who Are “the Homeless”? Reconsidering the Stability and Composition of the Homeless Population. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1334–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G. Fear of People with Mental Illnesses: The Role of Personal and Impersonal Contact and Exposure to Threat or Harm. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2004, 45, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H.; Moore, L.; Gruskin, S.; Krieger, N. Characterizing Perceived Police Violence: Implications for Public Health. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rando, J.; Broering, D.; Olson, J.E.; Marco, C.; Evans, S.B. Intranasal Naloxone Administration by Police First Responders Is Associated with Decreased Opioid Overdose Deaths. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, 33, 1201–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.; O’Toole, T.; Kearney, L.K. Homelessness as a Public Mental Health and Social Problem: New Knowledge and Solutions. Psychol. Serv. 2017, 14, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, H.J.; Palar, K.; Hufstedler, L.L.; Seligman, H.K.; Frongillo, E.A.; Weiser, S.D. Food Insecurity, Chronic Illness, and Gentrification in the San Francisco Bay Area: An Example of Structural Violence in United States Public Policy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 143, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

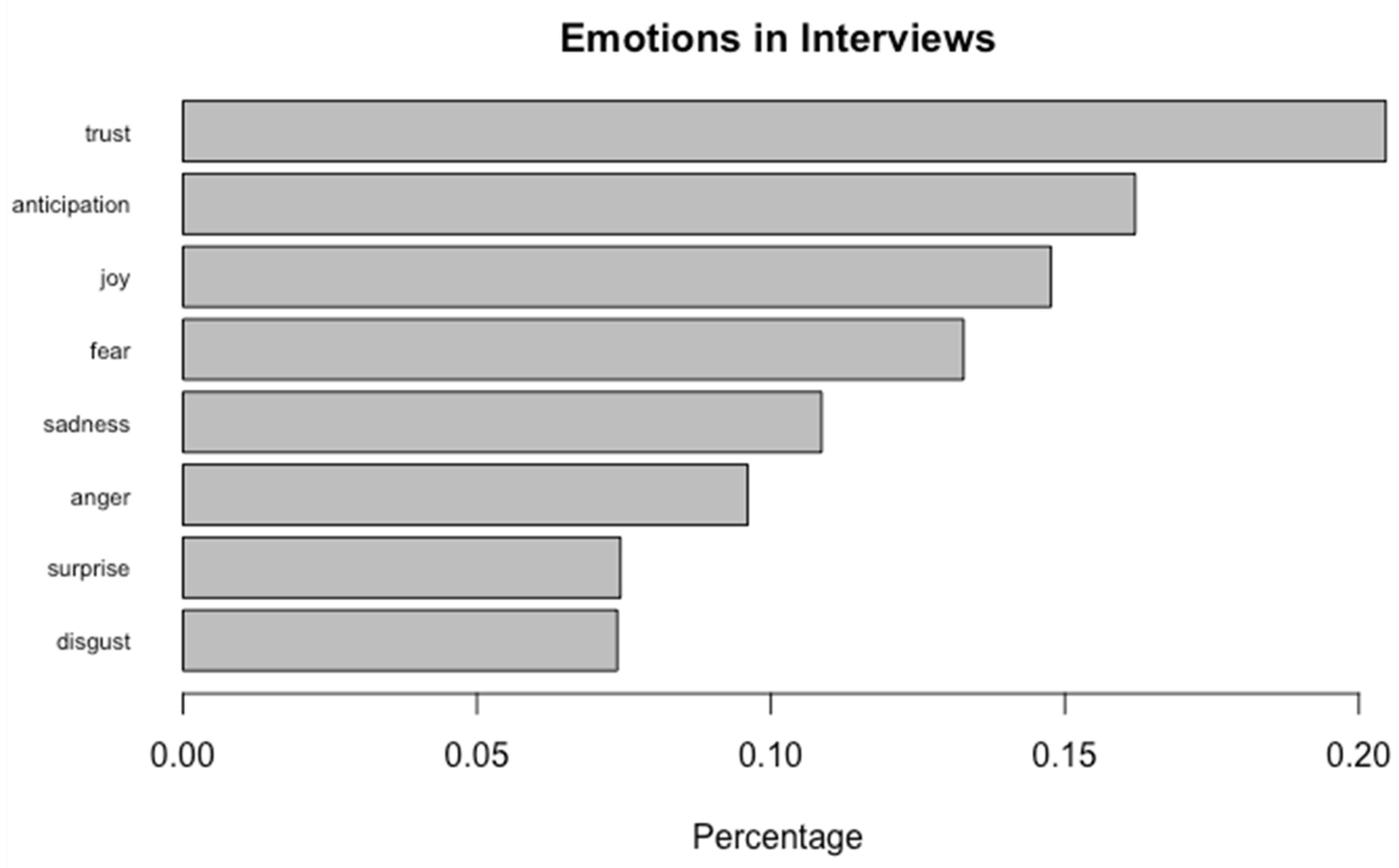

| Anger Sentences |

| “You’d go crazy.” “You wasted it.” “You know, what did you do when you legalized it?” “You know, we’ll just start killing civilians.” “You’ll be like, OK, that looks like they’re going to treat him for OD.” “You’ve got to yell at this guy, hey, stop asking for people’s money, going up to people’s cars.” “You make the choice to sell this, then therefore, you are contributing to the --downfall or eventual death.” “You know, there’s at one point that you come around this way you swing around and come up to get to Freedom Parkway, and there’s always been a homeless population under that bridge area.” “You know, we’ve been fighting this since the early--” “You’re more likely to get shot or hurt in Buckhead at the bar than you are here.” |

| Anticipation Sentences |

| “You’re not liable if you do something as a good Samaritan.” “You overdosed, and you’re alive but just because like this dude, G, kept him alive.” “You say you can’t have it out in public.” “You know, they have track marks and all that.” “You know, we’ll just start killing civilians.” “You’ll be like, OK, that looks like they’re going to treat him for OD.” “You’re just not having fun.” “You’ve got to yell at this guy, hey, stop asking for people’s money, going up to people’s cars.” “You make the choice to sell this, then therefore, you are contributing to the --downfall or eventual death.” “You want to make them feel like a responsible citizen again, and you do it a little bit at the time.” |

| Disgust Sentences |

| “You know, people come in all the time and want to buy food for the homeless people.” “You wasted it.” “You know, the cops are hanging around just asking the pharmacist, asking me, asking my co-workers, you know, what happened, yada, yada, yada.” “You know, like, when your skin starts rotting after that?” “You know, shit like that.” “You’ll be like, OK, that looks like they’re going to treat him for OD.” “You make the choice to sell this, then therefore, you are contributing to the --downfall or eventual death.” “You know, there’s at one point that you come around this way you swing around and come up to get to Freedom Parkway, and there’s always been a homeless population under that bridge area.” “You know, shipping containers that are no longer in use can be converted to living spaces to help reduce the homeless.” “You know, it’s like the spider web.” |

| Fear Sentences |

| “You’d go crazy.” “You know, the cops are hanging around just asking the pharmacist, asking me, asking my co-workers, you know, what happened, yada, yada, yada.” “You know, what did you do when you legalized it?” “You know, we’ll just start killing civilians.” “You’ll be like, OK, that looks like they’re going to treat him for OD.” “You’re just copping, and you’re just cop, gotta cop, gotta get some more, buy a lot.” “You’ve got to yell at this guy, hey, stop asking for people’s money, going up to people’s cars.” “You make the choice to sell this, then therefore, you are contributing to the --downfall or eventual death.” “You know, there’s at one point that you come around this way you swing around and come up to get to Freedom Parkway, and there’s always been a homeless population under that bridge area.” “You’re more likely to get shot or hurt in Buckhead at the bar than you are here.” |

| Joy Sentences |

| “You probably have to have two jobs just to afford to live around here, depending on what kind of job you have.” “You’re not liable if you do something as a good Samaritan.” “You overdosed, and you’re alive but just because like this dude, G, kept him alive.” “You know, what did you do when you legalized it?” “You’ll be like, OK, that looks like they’re going to treat him for OD.” “You’re just not having fun.” “You’ve got to yell at this guy, hey, stop asking for people’s money, going up to people’s cars.” “You need to have a little welcoming spot for your customers to come in, park, and feel safe.” “You know, there’s at one point that you come around this way you swing around and come up to get to Freedom Parkway, and there’s always been a homeless population under that bridge area.” “You know, we need facilities where if there’s-- we need mental health, safe use.” |

| Sadness Sentences |

| “You’d go crazy.” “You know, that generation, the older-- ?” “You know, the cops are hanging around just asking the pharmacist, asking me, asking my co-workers, you know, what happened, yada, yada, yada.” “You know, we’ll just start killing civilians.” “You know, you’d also get tax revenue on it, which could probably help wipe out the debt, I mean, if we’re not kidding.” “You’ll be like, OK, that looks like they’re going to treat him for OD.” “You make the choice to sell this, then therefore, you are contributing to the --downfall or eventual death.” “You remember R, with the big plats in his hair and then they fell off and stuff?” “You know, there’s at one point that you come around this way you swing around and come up to get to Freedom Parkway, and there’s always been a homeless population under that bridge area.” “You’re more likely to get shot or hurt in Buckhead at the bar than you are here.” |

| Surprise Sentences |

| “You just wanted to rubber neck the accident.” “You’re not liable if you do something as a good Samaritan.” “You’ll be like, OK, that looks like they’re going to treat him for OD.” “You’ve got to yell at this guy, hey, stop asking for people’s money, going up to people’s cars.” “You know, I’ve tried to guess, and I’m saying maybe 40.” “You make the choice to sell this, then therefore, you are contributing to the --downfall or eventual death.” “You’re more likely to get shot or hurt in Buckhead at the bar than you are here.” “You know, I haven’t gotten to the point where my emails say, my pronouns are, because I had to deal with certain types of people that don’t understand that.” “You know, here’s some money.” “You have to-- I mean, you kind of do have to have someone help you, or you have to have, I guess, methadone or something to, like, help wean you off of it.” |

| Trust Sentences |

| “You probably have to have two jobs just to afford to live around here, depending on what kind of job you have.” “You’re not liable if you do something as a good Samaritan.” “You overdosed, and you’re alive but just because like this dude, G, kept him alive.” “You think drugs should be legal.” “younger than her, she was real cooky.” “You’ll be like, OK, that looks like they’re going to treat him for OD.” “You’re just copping, and you’re just cop, gotta cop, gotta get some more, buy a lot.” “Your whole bowel, everything’s just fucked in your system.” “You’ve got to yell at this guy, hey, stop asking for people’s money, going up to people’s cars.” “You want to make them feel like a responsible citizen again, and you do it a little bit at the time.” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Febres-Cordero, S.; Smith, D.J. Stayin’ Alive in Little 5: Application of Sentiment Analysis to Investigate Emotions of Service Industry Workers Responding to Drug Overdoses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013103

Febres-Cordero S, Smith DJ. Stayin’ Alive in Little 5: Application of Sentiment Analysis to Investigate Emotions of Service Industry Workers Responding to Drug Overdoses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013103

Chicago/Turabian StyleFebres-Cordero, Sarah, and Daniel Jackson Smith. 2022. "Stayin’ Alive in Little 5: Application of Sentiment Analysis to Investigate Emotions of Service Industry Workers Responding to Drug Overdoses" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013103

APA StyleFebres-Cordero, S., & Smith, D. J. (2022). Stayin’ Alive in Little 5: Application of Sentiment Analysis to Investigate Emotions of Service Industry Workers Responding to Drug Overdoses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013103