Putting Policy into Practice: How Three Cancer Services Perform against Indigenous Health and Cancer Frameworks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design, Service Selection and Characteristics

2.2. Cultural and Ethical Considerations

2.3. Participant Recruitment and Profile

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

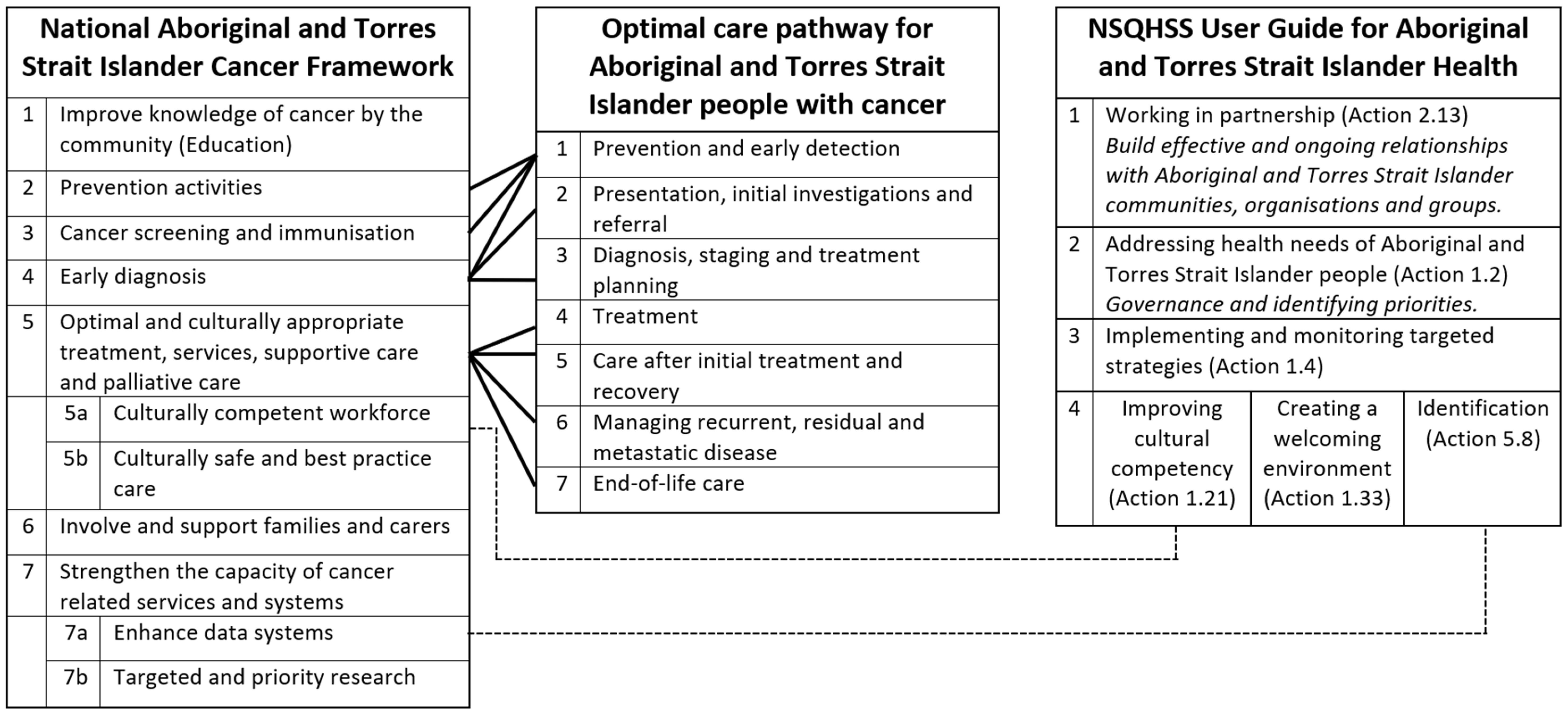

3.1. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Framework

3.1.1. Priority 1: Improve Knowledge, Attitudes and Understanding of Cancer by Individuals, Families, Carers and Community Members (across the Continuum)

| Priorities | Service A | Rating | Service B | Rating | Service C | Rating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Improve knowledge of cancer by the community (Education) |

| Not a focus |

| Emerging |

| Emerging |

| 2 | Prevention activities |

| Not a focus |

| Not a focus |

| Active |

| 3 | Cancer screening and immunisation |

| Not a focus |

| Not a focus |

| Active |

| 4 | Early diagnosis |

| Not a focus |

| Not a focus |

| Not a focus |

| 5 | Optimal and culturally appropriate treatment, services, supportive care and palliative care | ||||||

| 5a | Culturally competent workforce |

| Active |

| Not a focus |

| Active |

| 5b | Culturally safe and best practice care |

| Active |

| Not a focus |

| Active |

| 6 | Involve and support families and carers |

| Active |

| Not a focus |

| Active |

| 7 | Strengthen the capacity of cancer-related services and systems | ||||||

| 7a | Enhance data systems |

| Active |

| Not a focus |

| Active |

| 7b | Targeted and priority research |

| Emerging |

| Not a focus |

| Active |

| Actions | Service A | Rating | Service B | Rating | Service C | Rating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.13 | Working in partnership |

| Active |

| Active |

| Active |

| 1.2 | Addressing health needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people |

| Active |

| Not a focus |

| Active |

| 1.4 | Implementing and monitoring targeted strategies |

| Active |

| Not a focus |

| Active |

| 1.21 | Improving cultural competency |

| Active |

| Not a focus |

| Active |

| 1.33 | Creating a welcoming environment |

| Active |

| Not a focus |

| Active |

| 5.8 | Identifying people of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin |

| Active |

| Not a focus |

| Active |

3.1.2. Priority 2: Focus Prevention Activities to Address Specific Barriers and Enablers to Minimise Cancer Risk for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

…hard but we have to do it… at the moment prevention is left to primary care… cancer centres need to take on tackle prevention. We all see patients and we can do primary and secondary prevention… and really should not need extra funding.(Participant 13, Oncologist, non-Indigenous)

3.1.3. Priority 3: Increase Access to and Participation in Cancer Screening and Immunisations for the Prevention and Early Detection of Cancers

3.1.4. Priority 4: Ensure Early Diagnosis of Symptomatic Cancers

3.1.5. Priority 5: Ensure Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People Affected by Cancer Receive Optimal and Culturally Appropriate Treatment, Services and Supportive and Palliative Care

5a: Ensure a Skilled and Caring Workforce with Effective Cross-Cultural Communication Skills

5b: Ensure Aboriginal People Receive Best Practice Care

3.1.6. Priority 6: Ensure Families and Carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with Cancer Are Involved, Informed, Supported and Enabled throughout the Cancer Experience

3.1.7. Priority 7: Strengthen the Capacity of Cancer-Related Services and Systems to Deliver Good Quality, Integrated Services That Meet the Needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People

7a: Enhance Data Systems to Inform Better Outcomes

So I think it is around [Service B] and staff understanding why people don’t want to identify as Aboriginal. It is not just a matter of we are not asking the question. It is like we have to provide a safe environment for our Aboriginal patients to disclose their Aboriginality.(Participant 25, Director, non-Indigenous)

7b: Targeted and Priority Research to Inform Policy, Health Promotion, Service Provision and Clinical Practice

3.2. Health Standards User Guide

3.2.1. Action 2.13: Working in Partnership

The organisation brings all Aboriginal staff, so not just ALOs or managers, it’s nursing staff, it’s cleaners, it’s, you know, maintenance guys. Anyone who identifies as Aboriginal is welcome to go to that forum. And the CEO turns up… you have got the CEO of [health service] sitting at the table talking to Aboriginal staff at all levels.(Participant 8, Manager, Indigenous)

When we did our first data analysis I thought, ‘Alright, we are going to find a big cohort around <regional town>’ or something like that ‘and that will be our beginning link’, but, no… the patients were scattered across the whole state and the whole country. So, the difficulty then is how do you extend your tentacles into every single area to build those relationships?(Participant 32, Researcher, non-Indigenous)

3.2.2. Action 1.2: Addressing Health Needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People and Action 1.4: Implementing and Monitoring Targeted Strategies

We certainly do have the support of executive members to do what we need to do to have good outcomes <for Indigenous patients>. That doesn’t necessarily translate to a bottomless bucket of money, but, you know, we have opportunity to within the current structures and the framework is that we can be bold to do more.(Participant 7, Manager, Indigenous)

3.2.3. Action 1.21: Improving Cultural Competency

3.2.4. Action 1.33: Creating a Welcoming Environment

3.2.5. Action 5.8: Identifying People of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Origin

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The Health and Welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Available online: http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129550168 (accessed on 21 February 2021).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples of Australia. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-in-indigenous-australians/contents/table-of-contents (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Condon, J.; Zhang, X.; Baade, P.; Griffiths, K.; Cunningham, J.; Roder, D.; Coory, M.; Jelfs, P.; Threlfall, T. Cancer survival for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: A national study of survival rates and excess mortality. Popul. Health Metr. 2014, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Closing the Gap Prime Minister’s Report 2020. Available online: https://ctgreport.niaa.gov.au/content/closing-gap-2020 (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Durey, A.; Thompson, S.C. Reducing the health disparities of Indigenous Australians: Time to change focus. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moore, S.P.; Green, A.C.; Bray, F.; Garvey, G.; Coory, M.; Martin, J.; Valery, P.C. Survival disparities in Australia: An analysis of patterns of care and comorbidities among indigenous and non-indigenous cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Valery, P.C.; Coory, M.; Stirling, J.; Green, A.C. Cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survival in Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians: A matched cohort study. Lancet 2006, 367, 1842–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, M.; Burns, J.; Potter, C.; Elwell, M.; Hollows, M.; Mundy, J.; Taylor, E.; Thompson, S. Review of cancer among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Aust. Indig. HealthBulletin 2018, 18, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, S.; Finn, L.D.; Thompson, S.C. Barriers to participation of Aboriginal people in cancer care: Communication in the hospital setting. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 190, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, D. The meaning of cancer for Australian Aboriginal women changing the focus of cancer nursing. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. Off. J. Eur. Oncol. Nurs. Soc. 2009, 13, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, P.; Rawson, N. Key factors impacting on diagnosis and treatment for vulvar cancer for Indigenous women: Findings from Australia. Supportive Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Supportive Care Cancer 2013, 21, 2769–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMichael, C.; Kirk, M.; Manderson, L.; Hoban, E.; Potts, H. Indigenous women’s perceptions of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in Queensland. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2000, 24, 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.C.; Shahid, S.; Bessarab, D.; Durey, A.; Davidson, P.M. Not just bricks and mortar: Planning hospital cancer services for Aboriginal people. BMC Res. Notes 2011, 4, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lethborg, C.; Halatanu, F.; Mason, T.; Posenelli, S.; Cleak, H.; Braddy, L. Culturally Informed, Codesigned, Supportive Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with Cancer and Their Families. Aust. Soc. Work 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Australia. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Framework 2015. Available online: https://canceraustralia.gov.au/publications-and-resources/cancer-australia-publications/national-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-cancer-framework (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- Cancer Australia. Optimal Care Pathway for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with Cancer. Available online: https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/publications-and-resources/cancer-australia-publications/optimal-care-pathway-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-people-cancer (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards. Second Edition. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/National-Safety-and-Quality-Health-Service-Standards-second-edition.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- The Wardliparingga Aboriginal Research Unit of the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute. National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards User Guide for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/National-Safety-and-Quality-Health-Service-Standards-User-Guide-for-Aboriginal-and-Torres-Strait-Islander-Health.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Taylor, E.V.; Haigh, M.M.; Shahid, S.; Garvey, G.; Cunningham, J.; Holloway, M.; Thompson, S.C. Australian cancer services: A survey of providers’ efforts to meet the needs of Indigenous patients. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2018, 42, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, E.V.; Haigh, M.M.; Shaouli, S.; Garvey, G.; Cunningham, J.; Thompson, S.C. Cancer Services and Their Initiatives to Improve the Care of Indigenous Australians. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taylor, E.V.; Lyford, M.; Parsons, L.; Mason, T.; Sabesan, S.; Thompson, S.C. “We’re very much part of the team here”: A culture of respect for Indigenous health workforce transforms Indigenous health care. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.V.; Lyford, M.; Holloway, M.; Parsons, L.; Mason, T.; Sabesan, S.; Thompson, S.C. “The support has been brilliant”: Experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients attending two high performing cancer services. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikh, A. The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Values and Ethics: Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research; 1864962135; NHMRC: Canberra, Australia, 2003.

- Green, J.; Willis, K.; Hughes, E.; Small, R.; Welch, N.; Gibbs, L.; Daly, J. Generating best evidence from qualitative research: The role of data analysis. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2007, 31, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiklejohn, J.A.; Adams, J.; Valery, P.C.; Walpole, E.T.; Martin, J.H.; Williams, H.M.; Garvey, G. Health professional’s perspectives of the barriers and enablers to cancer care for Indigenous Australians. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2016, 25, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, S.; Finn, L.; Bessarab, D.; Thompson, S.C. ‘Nowhere to room… nobody told them’: Logistical and cultural impediments to Aboriginal peoples’ participation in cancer treatment. Aust. Health Rev. 2011, 35, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marcusson-Rababi, B.; Anderson, K.; Whop, L.J.; Butler, T.; Whitson, N.; Garvey, G. Does gynaecological cancer care meet the needs of Indigenous Australian women? Qualitative interviews with patients and care providers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Witt, A.; Matthews, V.; Bailie, R.; Valery, P.C.; Adams, J.; Garvey, G.; Martin, J.H.; Cunningham, F.C. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients’ cancer care pathways in Queensland: Insights from health professionals. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bygrave, A.; Whittaker, K.; Aranda, S. Inequalities in Cancer Outcomes by Indigenous Status and Socioeconomic Quintile: An Integrative Review. Available online: https://www.cancer.org.au/assets/pdf/inequalities-in-cancer-outcomes#_ga=2.123979722.1383640399.1641045996-1414787762.1630555519 (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Taylor, K.P.; Thompson, S.C. Closing the (service) gap: Exploring partnerships between Aboriginal and mainstream health services. Aust. Health Rev. 2011, 35, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.H.; Alam, K.; Gow, J.; Ralph, N. Predictors of health care use in Australian cancer patients. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 6941–6957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet. Closing the Gap. Available online: https://healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/learn/health-system/closing-the-gap/ (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Curtis, E.; Wikaire, E.; Stokes, K.; Reid, P. Addressing indigenous health workforce inequities: A literature review exploring ‘best’ practice for recruitment into tertiary health programmes. Int. J. Equity Health 2012, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Willis, J.; Wilson, G.; Renhard, R.; Chong, A.; Clarke, A. Improving the Culture of Hospitals Project: Final Report. Available online: http://www.lowitja.org.au/sites/default/files/docs/ICHP_Final_Report_August_2010.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2017).

- Bourke, L.; Mitchell, O.; Mohamed Shaburdin, Z.; Malatzky, C.; Anam, M.; Farmer, J. Building readiness for inclusive practice in mainstream health services: A pre-inclusion framework to deconstruct exclusion. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 289, 114449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taylor, E.V.; Lyford, M.; Parsons, L.; Holloway, M.; Gough, K.; Sabesan, S.; Thompson, S.C. Putting Policy into Practice: How Three Cancer Services Perform against Indigenous Health and Cancer Frameworks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020633

Taylor EV, Lyford M, Parsons L, Holloway M, Gough K, Sabesan S, Thompson SC. Putting Policy into Practice: How Three Cancer Services Perform against Indigenous Health and Cancer Frameworks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(2):633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020633

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaylor, Emma V., Marilyn Lyford, Lorraine Parsons, Michele Holloway, Karla Gough, Sabe Sabesan, and Sandra C. Thompson. 2022. "Putting Policy into Practice: How Three Cancer Services Perform against Indigenous Health and Cancer Frameworks" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 2: 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020633

APA StyleTaylor, E. V., Lyford, M., Parsons, L., Holloway, M., Gough, K., Sabesan, S., & Thompson, S. C. (2022). Putting Policy into Practice: How Three Cancer Services Perform against Indigenous Health and Cancer Frameworks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2), 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020633