3.1. Research Method

Based on the “capability approach” theory, Alkire and Foster [

43] designed a multidimensional poverty measurement method called the AF method. The method contains a deprivation dimension, weight distribution, multidimensional poverty identification, poverty aggregation and index decomposition, and is the basic method of MPI. This method has been the main tool used by domestic and foreign scholars to study multidimensional poverty thus far and has been recognized by many domestic and foreign scholars, organizations and governments [

44]. This study uses the AF method to measure and decompose the health poverty of rural residents.

First, in the setting of the value of the health poverty dimension, let represent the dimension matrix; n is the number of samples, and d is the dimension. Let represent the different values of n individuals in the d dimensions, where represents the value of the i-th rural resident in j dimension.

Second, define as the deprivation value on the j-th dimension and the deprivation matrix as = , to represent the deprivation of the rural residents. If a rural resident is deprived under a certain indicator, the value of this indicator in the deprivation matrix is 1; otherwise the value is 0, indicating a non-deprivation status. The weight is set for each dimension, and represents the deprivation value of individual i in the j dimension.

Again, define a column vector to represent the sum of the deprivation values of rural resident i in all dimensions, i.e., the column vector , . According to the critical value K of health poverty in the deprivation matrix, this study identified multidimensional health poverty for each sample: . Additionally, indicates that individual i is poor under the critical value criterion K. We zeroed the deprivation value of non-healthy poor individuals to eliminate the interference of the deprivation information of the unhealthy poor individuals on the aggregation of health poverty, and called the deprivation matrix after zeroing as the censored matrix (K) ().

The formula for calculating the HPI at this time is:

- (1)

Equation: H is the adjusted incidence of multidimensional health poverty, H = , q is the number of identified multidimensional health poverty rural residents, and n is the total number; is the average deprivation share, i.e., the intensity of deprivation, and , i.e., the weighted average of the deprivation score values of the multidimensional health poverty population.

Finally, based on the

calculated in Equation (1) above, the contribution of each indicator to health poverty is calculated:

- (2)

Equation: is the weight value of the i-th column indicator, and is the population rate of the i-th column indicator deprived in the deleted matrix.

3.2. MHPI Design

The traditional MPI includes 3 dimensions and 10 indicators [

43], specifically: (1) health, including nutritional status and child mortality; (2) education, including children’s enrolment rates and educational attainment, and (3) living standard, including household electricity, sanitation, drinking water, flooring type cooking fuel, and asset ownership. The measurement dimension of health poverty should take greater account of the combined effects of economic, social, health environment, equity and efficiency and other factors [

45]. Considering the current situation in China and the availability of data, this study expanded the MPI and designed an MHPI. The MHPI contains 5 dimensions, including (1) individual economic income, (2) individual health endowment, (3) individual health literacy and behavior, (4) healthy living environment, and (5) health service and security rights, as well as 17 secondary indicators.

Table 1 details the dimensions, indicators, weights, and deprivation threshold.

The first index dimension is economic income. Select the per capita annual net income of households as the measurement index. Under the connotation of relative poverty, defining poverty according to a certain proportion of the average or median income of the society has become international common practice. This study considered those households whose per capita annual net income was lower than the median income of the sample group in the current year as experiencing economic poverty.

The second index dimension is individual health endowment. (1) The body mass index (BMI) is the most common tool used internationally to measure an individual’s weight to height ratio. This method was officially proposed by Keys et al. [

46]. The calculation formula is as follows: BMI = weight (kg)/height

2. On this basis, the critical value used to judge the degree to which Chinese adults are overweight and obese, as proposed by the Working Group on Obesity in China, is as follows: when the index is between 18.5 and 24, the adult is in a normal healthy state; outside this range is considered unhealthy. (2) Next, SRH is a variable frequently used in most literature to reflect the health status of individuals. In practice, SRH can comprehensively reflect the multidimensional nature and integrity of health [

47,

48]. In this study, those who rated themselves as unhealthy were considered to be in a state of health deprivation; the remaining respondents were considered to be in a state of health. (3) Chronic disease: disease is the biggest health threat faced by the rural poor in China [

49]. The “Healthy China 2030 Blueprint” issued by the Chinese government in 2016 regarded major chronic diseases as indicators of premature mortality. Therefore, individuals with chronic diseases or those who were hospitalized due to illness in the previous 12 months were considered to be in a state of health deprivation in this study.

The third index dimension is individual health literacy and behavior. Referring to the indicators of the health literacy level of residents, developed by the Chinese Center for Health Education [

50], and combined with the availability of data, this study designed six indicators representing the level of health literacy and behavior. Those indicators include: (1) whether an individual engages in smoking and alcohol abuse (smoking and drinking habits are generally considered unhealthy) [

51]. (2) whether the person exercises. Regular physical activity contributes to good health [

52]. (3) Health consumption expenditure: if the proportion of personal health consumption expenditure to total expenditure was lower than the median of the sample, these people were considered to be unwilling or unable to afford the normal level of health consumption expenditure [

53], and their health literacy was low. (4) Choice of medical institution: those who can actively choose to go to formal medical institutions when seeking medical treatment were considered to have higher health literacy. Those who could not make such choices were considered to have lower health literacy and unscientific medical seeking behavior. (5) Hospitalization or not: those who were willing to accept hospitalization when they were sick were considered to have a high level of health literacy and scientific medical behavior, and vice versa. (6) Garbage dumping site selection: those who can take the initiative to choose a public garbage collection site to dump their garbage were considered to have high health literacy, while those who did not or could not make such choices were considered to have low health literacy and unscientific hygiene habits.

The fourth index dimension is the healthy living environment. Referring to the indicators of living environment in MPI, this study designed indicators in two dimensions: home environment and surrounding community environment. (1) Cooking water, cooking fuel and toilet type were selected as the proxy indicators of the home environment. The households whose cooking water was tap water and bottled water, the cooking fuel was non-firewood, and the toilet was flushing type were considered to have a healthy home environment. If the converse was true, the home environment was regarded as unhealthy [

54,

55]. (2) A community without highly-polluting enterprises within five kilometers of the residence was regarded as having a healthy community environment. Conversely, the community environment was regarded as unhealthy if highly-polluting enterprises were nearby [

56].

The last index dimension is the health service and security rights. This type of indicator should include the two dimensions of residents’ health expenditure security and public health service sharing rights. The former mainly reflects the compensation of disease expenditure; the latter mainly reflects the degree of equalization of public health services and security. First, as a remedial measure to diversify the family’s economic risks [

57], medical insurance can compensate for the economic losses caused by the risk of illness. This study uses medical insurance as a proxy indicator variable for health expenditure security, and considers rural residents who did not participate in any medical insurance schemes as being deprived of health expenditure security. Secondly, referring to the practice of Liu et al. [

58], the number of medical and health workers per capita in the community, and the evaluation of the level of community medical services, are used as proxy indicator variables for the sharing rights of basic health services. The rural residents whose per capita number of medical and health workers was lower than the median and whose evaluation of the medical service level of the medical institutions was unsatisfactory were regarded as being deprived of the right to share health services.

Due to the large number of indicators involved in the study, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to test the multicollinearity of variables in the MHPI system.

Table 2 reports the results. The VIF values range from 1.00 to 1.25, with an average VIF of 1.10; and all VIF values are below 5 [

59]. These results indicate that there is no significant co-linearity in the variables.

3.3. Data Collection and Descriptive Analysis

This study uses data from China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), conducted by the Institute of Social Science Survey [

60]. These data are from a large nationally representative micro-integrated family social tracking survey, which is conducted every two years and covers 25 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions. The population of the sample area accounts for 94.5% of China’s total population, and the target sample size is 16,000 households. Hence, this study has the advantages of large sample size and wide coverage. The survey adopts a stratified multi-stage sampling design (sampling protocol is publicly available at

www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/ (accessed on 13 September 2022)) and contains four sections: community questionnaire, family questionnaire, adult questionnaire and children’s questionnaire. The survey’s design and various sections fully reflect the changes in China’s economy, society, population, education development and personal health [

61]. This survey has been ethically reviewed (approval number: IRB00001052-14010), thereby providing real and reliable data for academic research and public policy analysis in various fields of the social sciences [

62].

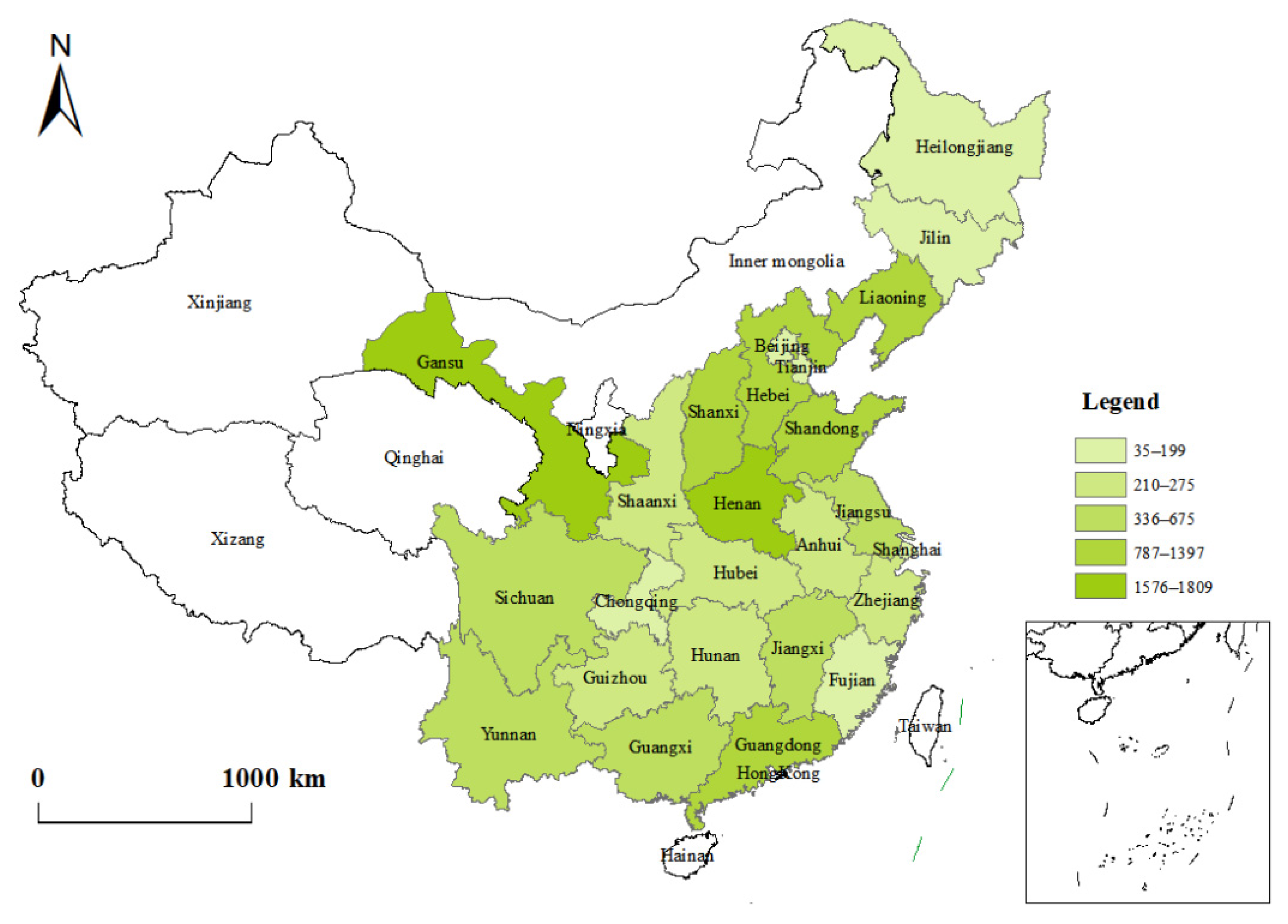

Since the 2010 baseline survey, CFPS has conducted five rounds of follow-up surveys. This study uses data collected by CFPS in 2016 and 2018. Indicators such as “SRH”, “chronic diseases”, “smoking” and “drinking” come from the adult questionnaire. Indicators such as “water for cooking”, “fuel for cooking” and “toilet type” come from the family questionnaire. Indicators such as “highly polluting enterprises” and “number of medical and health workers” come from the community questionnaires. Each part of the questionnaires contains a wide range of questions, which fully reflects the various aspects of rural residents’ personal health and family life. As such, the questionnaires can better measure the diversity of rural residents’ health poverty in different regions of China. In order to improve the accuracy and integrity of the characteristic variables and data after questionnaire merging, this study conducted descriptive statistics on the basic characteristics of the samples; any samples with missing data and obvious outliers were eliminated. Ultimately, a total of 13,151 samples from 25 provinces were obtained, and the specific sample distribution is shown in

Figure 1. Detailed socio-demographic statistics are shown in

Table 3.

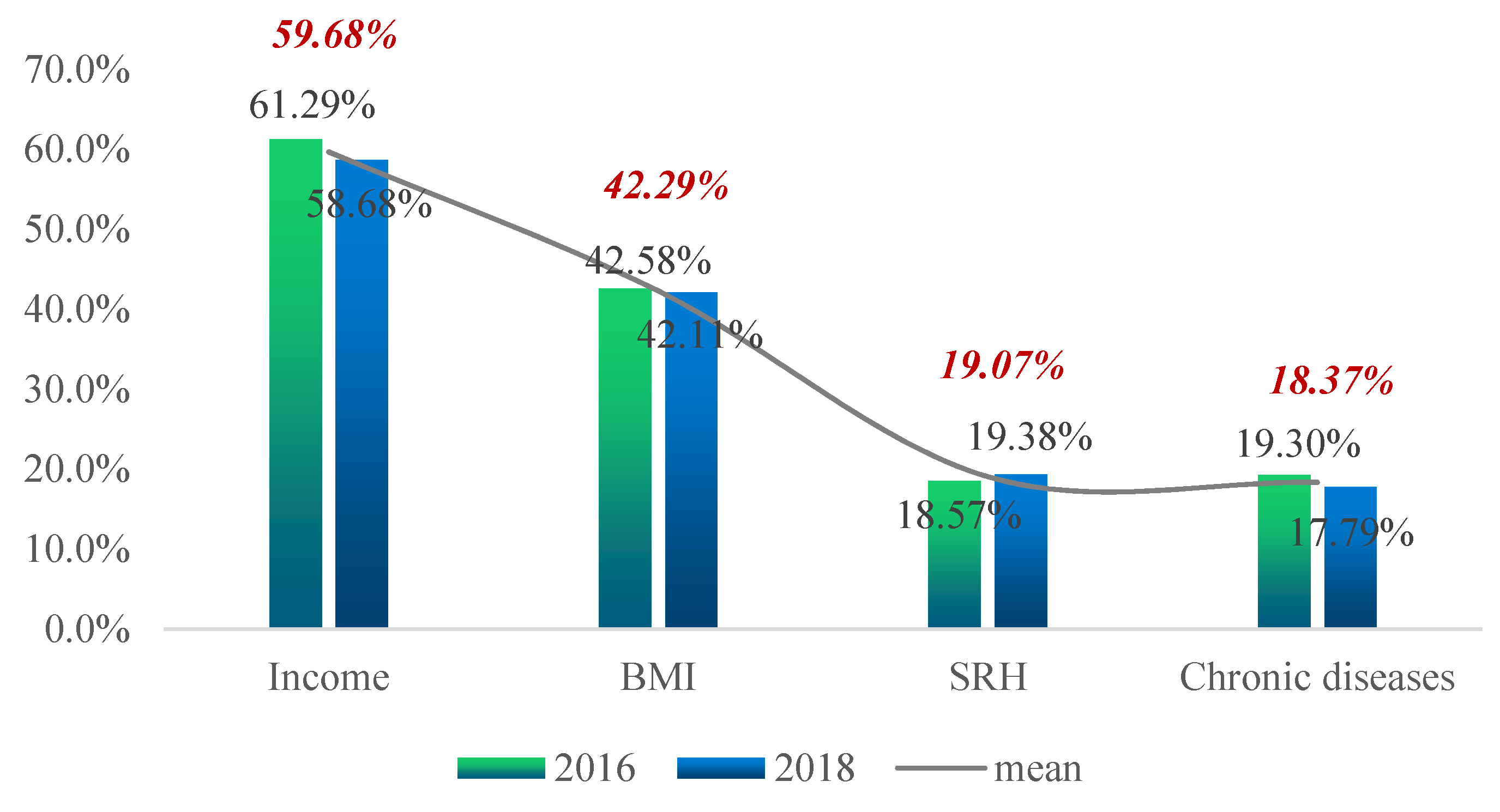

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the proportion of the population in deprivation (i.e., health poverty) in the total sample under each of the five dimensions; the data for two years are also compared.

Figure 2 shows that, from the two-year mean, the proportion of the population that had “per capita annual net income of households” below the relative poverty line was the highest, at 59.86%. The proportion of the population suffering from “chronic diseases” was the lowest, at 18.37%. By comparing the two-year data, one can see that, except for the increase in the proportion of health poverty people in “SRH”, all other indicators showed a downward trend.

Figure 3 shows that, from the two-year mean, the proportion of health poverty people in the indicator of “health consumption” was the highest, at 90.27%. The proportion of health poverty people in the indicator of “hospitalization or not” was the lowest, at 13.62%. The other indicators were roughly the same. By comparing the two-year data, one can see that, except for the slight increase in the proportion of the health poverty population in the indicator of “hospitalization or not”, the proportions of the other indicators decreased significantly.

Figure 4 shows that, from the two-year mean, the proportion of health poverty people in the indicator of “toilet type” was the highest, at 71.79%. The proportion of “high-pollution enterprises” was the lowest, at 16.61%. By comparing the two-year data, one can see that the proportion of health poverty people in the indicator of “cooking water” and “highly-polluting enterprises” increased slightly, while the rest decreased.

Figure 5 shows that, from the two-year mean, the proportion of health poverty people in the indicator of “number of medical and health workers” was the highest, at 50.22%. The proportion of those in “medical insurance” was the lowest, at 5.44%. By comparing the two-year data, one can see that the proportions of the health poverty in the three indicators increased to different degrees. The highest increase was the “medical level evaluation”, with an increase of 6.15 percentage points.