Adulthood Employment Trajectories and Later Life Mental Health before and after the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Gaps

1.2. The Study Field of Employment Trajectories and Later Life Health

1.3. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

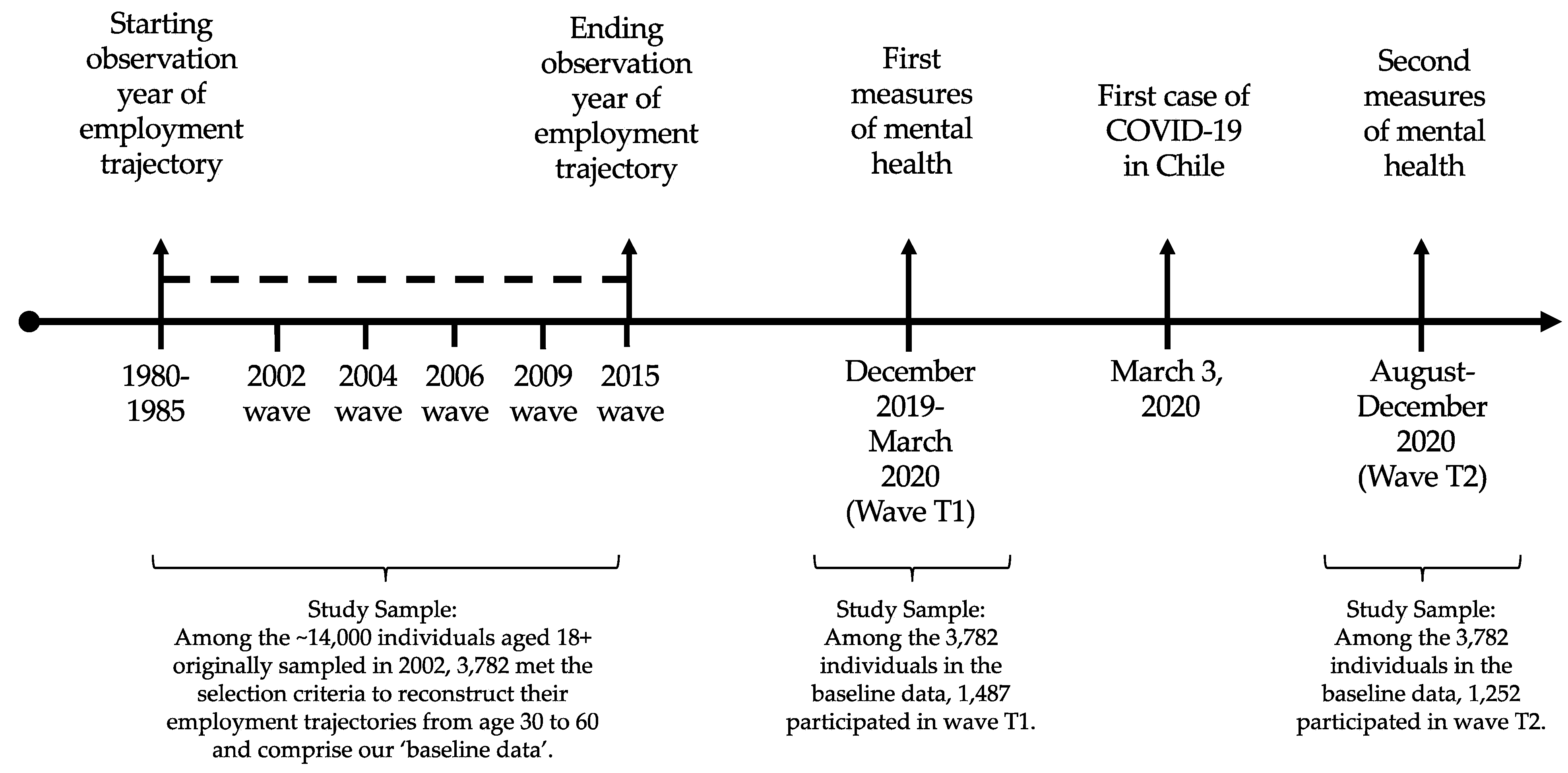

2.1. Longitudinal Data

2.2. Survey Waves Used in This Study and Sample Derivation

2.3. Study Samples

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Independent Variable: Employment Trajectories in Adulthood

2.4.2. Dependent Variables: Depressive Symptoms before and after the Onset of the Pandemic

2.4.3. Control Variables

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Univariate Descriptive Statistics

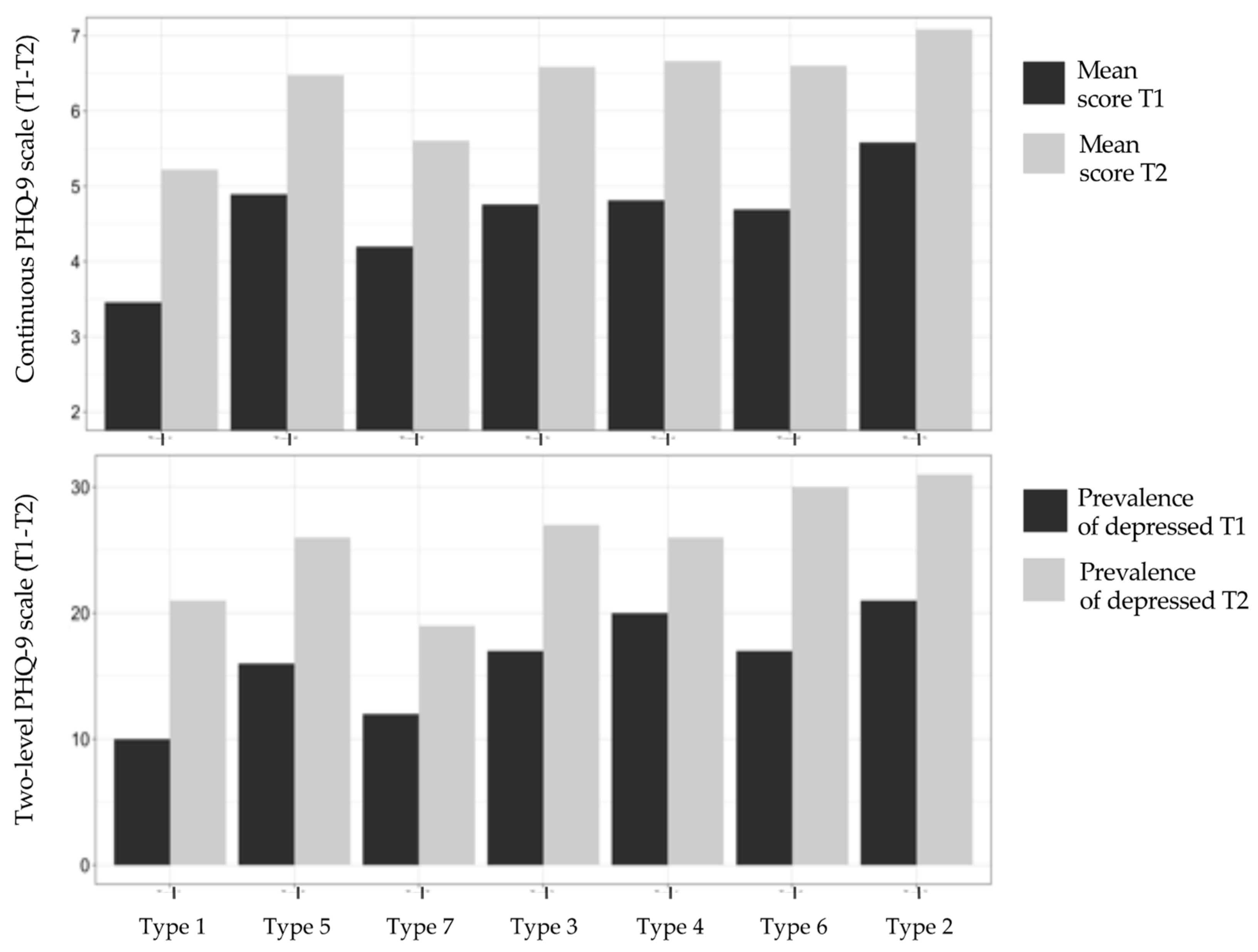

3.2. Bivariate Associations between Employment Trajectories and Mental Health Outcomes

3.2.1. Formal Employment Trajectories

3.2.2. Informal Employment Trajectories

3.2.3. Non-Employment Trajectories

3.3. Employment Trajectories and Mental Health Outcomes: Multivariate Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Whole Sample | Type 1. Conventional Work Life Cycle | Type 2. Out of the Labor Force | Type 3. Full-Time Self-Employed Not Contributing | Type 4. Wage-Earners Not Contributing | Type 5. Full-Time Self-Employed Contributing | Type 6. Part-Time Self-Employed Not Contributing | Type 7. Part-Time Wage-Earners Contributing | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 |

| Age (Mean, SD) | 67.7 (4.3) | 67.4 (4.3) | 67.8 (4.4) | 67.7 (4.3) | 67.2 (4.3) | 66.8 (4.3) | 67.7 (4.2) | 67.5 (4.5) | 67.7 (4.1) | 66.8 (4.5) | 68.1 (4.1) | 68.5 (4.5) | 68.3 (4.5) | 68.1 (3.4) | 69.3 (3.9) | 68.3 (3.2) |

| Gender (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Men | 41.2 | 43.4 | 59.2 | 60.6 | 7.1 | 7.8 | 72.9 | 74.8 | 36.8 | 47.1 | 80.0 | 66.0 | 48.4 | 43.3 | 30.4 | 16.1 |

| Women | 58.8 | 56.6 | 40.8 | 39.4 | 92.9 | 92.2 | 27.1 | 25.2 | 63.2 | 52.9 | 20.0 | 34.0 | 51.6 | 56.7 | 69.6 | 83.9 |

| Education (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| None or primary | 43.2 | 40.1 | 34.2 | 28.9 | 51.7 | 51.3 | 49.2 | 48.9 | 52.9 | 58.8 | 32.7 | 30.0 | 64.5 | 53.3 | 34.8 | 22.6 |

| Secondary | 44.8 | 44.2 | 48.0 | 46.5 | 43.5 | 42.4 | 44.9 | 43.5 | 41.2 | 39.7 | 43.6 | 48.0 | 35.5 | 46.7 | 21.7 | 29.0 |

| Tertiary | 12.0 | 15.7 | 17.8 | 24.6 | 4.8 | 6.3 | 5.9 | 7.6 | 5.9 | 1.5 | 23.6 | 22.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 43.5 | 48.4 |

| Number of chronic diseases (Mean, SD) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.1) | 0.9 (1.0) | 0.9 (1.0) | 1.4 (1.2) | 1.3 (1.2) | 0.9 (1.1) | 1.0 (1.2) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.2) | 1.1 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.5) | 1.1 (1.4) | 1.0 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.1) |

| Number of functional limitations (Mean, SD) | 0.4 (1.1) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.5 (1.3) | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.4 (1.3) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.6 (1.2) | 0.4 (1.0) |

| Number of children (Mean, SD) | 2.9 (1.7) | 2.7 (1.7) | 2.6 (1.6) | 2.5 (1.5) | 3.1 (1.7) | 3.0 (1.8) | 3.2 (2.2) | 2.8 (1.7) | 3.0 (1.5) | 2.6 (1.7) | 2.8 (1.8) | 2.9 (1.8) | 2.9 (1.6) | 2.6 (1.5) | 2.5 (1.8) | 2.5 (1.9) |

| Household income decile (Mean, SD) | 5.4 (2.8) | 5.4 (2.8) | 5.3 (2.9) | 5.3 (2.9) | 5.7 (2.7) | 5.7 (2.7) | 5.1 (2.7) | 5.3 (2.8) | 5.2 (2.4) | 4.7 (2.7) | 4.9 (3.2) | 4.6 (3.0) | 5.7 (2.9) | 5.1 (2.8) | 5.3 (3.1) | 5.9 (2.8) |

| Marital status (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Divorced | 12.7 | 12.1 | 13.8 | 12.8 | 13.0 | 11.4 | 11.0 | 13.7 | 11.8 | 7.4 | 5.5 | 12.0 | 12.9 | 13.3 | 8.7 | 12.9 |

| Partnered | 69.2 | 67.4 | 68.9 | 67.0 | 67.5 | 67.7 | 72.0 | 67.2 | 66.2 | 70.6 | 85.5 | 74.0 | 74.2 | 73.3 | 60.9 | 48.4 |

| Single | 10.0 | 11.8 | 11.7 | 13.7 | 8.9 | 9.1 | 6.8 | 10.7 | 7.4 | 16.2 | 7.3 | 4.0 | 9.7 | 6.7 | 21.7 | 25.8 |

| Widow | 8.1 | 8.6 | 5.7 | 6.4 | 10.6 | 11.9 | 10.2 | 8.4 | 14.7 | 5.9 | 1.8 | 10.0 | 3.2 | 6.7 | 8.7 | 12.9 |

| Drink wine (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 27.8 | 30.4 | 33.6 | 38.5 | 18.0 | 17.4 | 36.4 | 33.6 | 27.9 | 36.8 | 38.2 | 34.0 | 19.4 | 33.3 | 26.1 | 19.4 |

| No | 72.2 | 69.6 | 66.4 | 61.5 | 82.0 | 82.6 | 63.6 | 66.4 | 72.1 | 63.2 | 61.8 | 66.0 | 80.6 | 66.7 | 73.9 | 80.6 |

| Drink liquor (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 7.7 | 8.2 | 9.7 | 10.8 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 14.4 | 9.2 | 11.8 | 11.8 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 13.0 | 6.5 |

| No | 92.3 | 91.8 | 90.3 | 89.2 | 96.5 | 95.7 | 85.6 | 90.8 | 88.2 | 88.2 | 94.5 | 94.0 | 100 | 93.3 | 87.0 | 93.5 |

| Smoke (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 21.9 | 23.2 | 22.1 | 24.1 | 21.6 | 22.3 | 25.4 | 26.7 | 22.1 | 26.5 | 21.8 | 18.0 | 19.4 | 16.7 | 8.7 | 12.9 |

| No | 78.1 | 76.8 | 77.9 | 75.9 | 78.4 | 77.7 | 74.6 | 73.3 | 77.9 | 73.5 | 78.2 | 82.0 | 80.6 | 83.3 | 91.3 | 87.1 |

| Drink beer (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 18.1 | 21.3 | 24.5 | 27.9 | 8.9 | 10.1 | 26.3 | 26.7 | 19.1 | 23.5 | 23.6 | 30.0 | 3.2 | 20.0 | 8.7 | 6.5 |

| No | 81.9 | 78.7 | 75.5 | 72.1 | 91.1 | 89.9 | 73.7 | 73.3 | 80.9 | 76.5 | 76.4 | 70.0 | 96.8 | 80.0 | 91.3 | 93.5 |

Appendix B

| Formal Employment Trajectories | Informal Employment Trajectories | Non-Employment Trajectories | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1. Conventional Work Life Cycle | Type 5. Full-Time Self-Employed Contributing | Type 7. Part-Time Wage-Earners Contributing | Type 3. Full-Time Self-Employed Not Contributing | Type 4. Wage-Earners Not Contributing | Type 6. Part-Time Self-Employed Not Contributing | Type 2. Out of the Labor Force | ||||||||

| Variables | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 |

| Continuous PHQ-9 scale (mean, SD) | 3.5 (4.9) | 5.2 (5.8) | 4.9 (6.3) | 6.5 (5.9) | 4.2 (5.7) | 5.6 (6.2) | 4.8 (5.9) | 6.6 (6.1) | 4.8 (5.6) | 6.7 (6.8) | 4.7 (5) | 6.6 (5.5) | 5.6 (5.6) | 7.1 (6.3) |

| Five-level PHQ-9 scale (%) | ||||||||||||||

| None | 70.3 | 58.2 | 63.9 | 48.1 | 67.8 | 52.3 | 65.2 | 48.7 | 62.3 | 48.6 | 57.6 | 39.5 | 52.6 | 43.6 |

| Mild | 19.1 | 20.3 | 21.2 | 26.3 | 19.7 | 28.7 | 18.2 | 23.7 | 19.1 | 24.8 | 24.9 | 30.1 | 26.1 | 24.9 |

| Moderate | 6.3 | 12.1 | 3.1 | 11.7 | 4.2 | 13 | 8.8 | 14.3 | 11.2 | 13.2 | 8.1 | 22.8 | 13.1 | 15.1 |

| Moderately severe | 3.1 | 6.2 | 8.9 | 12.0 | 4.1 | 0.4 | 3.9 | 8.1 | 5.6 | 6.2 | 8.1 | 3.3 | 4.1 | 11.2 |

| Severe | 2.2 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 4.2 | 5.6 | 3.9 | 5.2 | 1.8 | 7.2 | 1.3 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 5.2 |

| Two-level PHQ-9 scale (%) | ||||||||||||||

| Depressed | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.39 (0.53) | 1.23 (0.36) | 1.25 (0.74) | .92 (0.38) | 1.46 (0.39) | 1.26 (0.24) | 1.83 (0.56) | 1.25 (0.32) | 1.85 (0.79) | 1.42 (0.49) | 1.93 (0.56) | 1.47 (0.19) |

Appendix C

| Before Pandemic Onset | After Pandemic Onset | |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | |

| Variables | Continuous PHQ-9 Scale | Continuous PHQ-9 Scale |

| Employment trajectory type | ||

| Formal employment trajectories (ref) | - | - |

| Informal employment trajectories | 0.79 (0.41) | 1.04 * (0.51) |

| Non-employment trajectories | 0.18 (0.38) | −0.09 (0.49) |

| Constant | 8.96 *** (2.39) | 8.39 ** (3.078) |

| R-Squared | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| N | 1315 | 1094 |

Appendix D

| Before Pandemic Onset | After Pandemic Onset | |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | |

| Variables | Continuous PHQ-9 Scale | Continuous PHQ-9 Scale |

| Employment trajectory type (Ref: Type 1. Conventional work life cycle) | - | - |

| Formal employment trajectories | ||

| Type 5. Full-time self-employed contributing | 1.68 * (0.73) | 1.07 (0.99) |

| Type 7. Part-time wage-earners contributing | 0.01 (1.1) | −0.41 (1.15) |

| Informal employment trajectories | ||

| Type 3. Full-time self-employed not contributing | 1.13 * (0.524) | 1.59 * (0.628) |

| Type 4. Wage-earners not contributing | 0.67 (0.67) | 0.27 (0.84) |

| Type 6. Part-time self-employed not contributing | 0.75 (0.96) | 0.71 (1.3) |

| Non-employment trajectories | ||

| Type 2. Out of the labor force | 0.26 (0.39) | −0.12 (0.51) |

| Constant | 8.90 *** (2.39) | 8.48 ** (3.16) |

| R-Squared | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| N | 1315 | 1094 |

References

- Villalobos Dintrans, P.; Browne, J.; Madero-Cabib, I. It Is Not Just Mortality: A Call From Chile for Comprehensive COVID-19 Policy Responses among Older People. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, e275–e280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girgus, J.S.; Yang, K. Gender and Depression. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 4, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horesh, D.; Lev-Ari, R.K.; Hasson-Ohayon, I. Risk Factors for Psychological Distress during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Israel: Loneliness, Age, Gender, and Health Status Play an Important Role. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavsson, J.; Beckman, L. Compliance to Recommendations and Mental Health Consequences among Elderly in Sweden during the Initial Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Cross Sectional Online Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpino, B.; Pasqualini, M.; Bordone, V.; Solé-Auró, A. Older People’s Nonphysical Contacts and Depression during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingerman, K.L.; Ng, Y.T.; Zhang, S.; Britt, K.; Colera, G.; Birditt, K.S.; Charles, S.T. Living Alone during COVID-19: Social Contact and Emotional Well-Being among Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, e116–e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, Y.S.; Cohen-Fridel, S.; Shrira, A.; Bodner, E.; Palgi, Y. COVID-19 Health Worries and Anxiety Symptoms among Older Adults: The Moderating Role of Ageism. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1371–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, L.; Romero-Ferreiro, V.; López-Roldán, P.D.; Padilla, S.; Rodriguez-Jimenez, R. Mental Health in Elderly Spanish People in Times of COVID-19 Outbreak. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, C.N.; Peng, C.; Mutchler, J.E.; Burr, J.A. Race and Ethnic Group Disparities in Emotional Distress among Older Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polenick, C.A.; Perbix, E.A.; Salwi, S.M.; Maust, D.T.; Birditt, K.S.; Brooks, J.M. Loneliness during the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Older Adults with Chronic Conditions. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Fokkema, T.; Switsers, L.; Dury, S.; Hoens, S.; De Donder, L. Older Chinese Migrants in Coronavirus Pandemic: Exploring Risk and Protective Factors to Increased Loneliness. Eur. J. Ageing 2021, 18, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Xu, Y.; Jedwab, M. Custodial Grandparent’s Job Loss during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Relationship with Parenting Stress and Mental Health. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, B.R. COVID-19 as a Stressor: Pandemic Expectations, Perceived Stress, and Negative Affect in Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, e59–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creese, B.; Khan, Z.; Henley, W.; O’Dwyer, S.; Corbett, A.; Vasconcelos Da Silva, M.; Mills, K.; Wright, N.; Testad, I.; Aarsland, D.; et al. Loneliness, Physical Activity, and Mental Health during COVID-19: A Longitudinal Analysis of Depression and Anxiety in Adults over the Age of 50 between 2015 and 2020. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2021, 33, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, M.; Hope, H.; Ford, T.; Hatch, S.; Hotopf, M.; John, A.; Kontopantelis, E.; Webb, R.; Wessely, S.; McManus, S.; et al. Mental Health before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Probability Sample Survey of the UK Population. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaaya, M.; Sibai, A.M.; Tabbal, N.; Chemaitelly, H.; El Roueiheb, Z.; Slim, Z.N. Work and Mental Health: The Case of Older Men Living in Underprivileged Communities in Lebanon. Ageing Soc. 2010, 30, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Ailshire, J.; Crimmins, E.M. Social Engagement and Depressive Symptoms: Do Baseline Depression Status and Type of Social Activities Make a Difference? Age Ageing 2016, 45, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worach-Kardas, H.; Kostrzewski, S. Quality of Life and Health State of Long—Term Unemployed in Older Production Age. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2014, 9, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Nonaka, K.; Hasebe, M.; Koike, T.; Minami, U.; Murayama, H.; Matsunaga, H.; Kobayashi, E.; Fujiwara, Y. Working for Only Financial Reasons Attenuates the Health Effects of Working beyond Retirement Age: A 2-year Longitudinal Study. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2020, 20, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behncke, S. Does Retirement Trigger Ill Health? Health Econ. 2012, 21, 282–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, D.; Rashad, I.; Spasojevic, J. The Effects of Retirement on Physical and Mental Health Outcomes. South. Econ. J. 2008, 75, 497–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, W.T.; Bradley, E.H.; Dubin, J.A.; Jones, R.N.; Falba, T.A.; Teng, H.-M.; Kasl, S.V. The Persistence of Depressive Symptoms in Older Workers Who Experience Involuntary Job Loss: Results From the Health and Retirement Survey. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2006, 61, S221–S228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokuda, Y.; Ohde, S.; Takahashi, O.; Shakudo, M.; Yanai, H.; Shimbo, T.; Fukuhara, S.; Hinohara, S.; Fukui, T. Relationships between Working Status and Health or Health-Care Utilization among Japanese Elderly. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2008, 8, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engels, M.; Wahrendorf, M.; Dragano, N.; McMunn, A.; Deindl, C. Multiple Social Roles in Early Adulthood and Later Mental Health in Different Labour Market Contexts. Adv. Life Course Res. 2021, 50, 100432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoven, H.; Wahrendorf, M.; Goldberg, M.; Zins, M.; Siegrist, J. Cumulative Disadvantage during Employment Careers—The Link between Employment Histories and Stressful Working Conditions. Adv. Life Course Res. 2020, 46, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settersten, R.A.; Bernardi, L.; Härkönen, J.; Antonucci, T.C.; Dykstra, P.A.; Heckhausen, J.; Kuh, D.; Mayer, K.U.; Moen, P.; Mortimer, J.T.; et al. Understanding the Effects of COVID-19 through a Life Course Lens. Adv. Life Course Res. 2020, 45, 100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahrendorf, M.; Blane, D.; Bartley, M.; Dragano, N.; Siegrist, J. Working Conditions in Mid-Life and Mental Health in Older Ages. Adv. Life Course Res. 2013, 18, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madero-Cabib, I.; Biehl, A.; Sehnbruch, K.; Calvo, E.; Bertranou, F. Private Pension Systems Built on Precarious Foundations: A Cohort Study of Labor-Force Trajectories in Chile. Res. Aging 2019, 41, 961–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madero-Cabib, I.; Azar, A.; Guerra, J. Simultaneous Employment and Depressive Symptom Trajectories around Retirement Age in Chile. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, M.; Weyers, S.; Moebus, S.; Jöckel, K.-H.; Erbel, R.; Pesch, B.; Behrens, T.; Dragano, N.; Wahrendorf, M. Gendered Work-Family Trajectories and Depression at Older Age. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 1478–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudici, F.; Morselli, D. 20 Years in the World of Work: A Study of (Nonstandard) Occupational Trajectories and Health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 224, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, T.; Forder, P.M.; Mishra, G.; Kendig, H.; Byles, J.E. Exploring Workforce Participation Patterns and Chronic Diseases Among Middle-Aged Australian Men and Women Over the Life Course. J. Aging Health 2017, 29, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zella, S.; Harper, S. The Impact of Life Course Employment and Domestic Duties on the Well-Being of Retired Women and the Social Protection Systems That Frame This. J. Aging Health 2020, 32, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickrama, K.A.S.; King, V.A.; O’Neal, C.W.; Lorenz, F.O. Stressful Work Trajectories and Depressive Symptoms in Middle-Aged Couples: Moderating Effect of Marital Warmth. J. Aging Health 2019, 31, 484–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahrendorf, M.; Hoven, H.; Deindl, C.; Lunau, T.; Zaninotto, P. Adverse Employment Histories, Later Health Functioning and National Labor Market Policies: European Findings Based on Life-History Data From SHARE and ELSA. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76 (Suppl. 1), S27–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madero-Cabib, I.; Biehl, A. Lifetime Employment–Coresidential Trajectories and Extended Working Life in Chile. J. Econ. Ageing 2021, 19, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baader, T.; Molina, J.L.; Venezian, S.; Rojas, C.; Farías, R.; Fierro-Freixenet, C.; Backenstrass, M.; Mundt, C. Validación y utilidad de la encuesta PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire) en el diagnóstico de depresión en pacientes usuarios de atención primaria en Chile. Rev. Chil. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2012, 50, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Höppner, J. How Does Self-employment Affect Pension Income? A Comparative Analysis of European Welfare States. Soc. Policy Adm. 2021, 55, 921–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.; Walker, E.A. Self-Employment: Policy Panacea for an Ageing Population? Small Enterp. Res. 2011, 18, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morselli, D.; Le Goff, J.M.; Gauthier, J.A. Self-administered event history calendars: A possibility for surveys? Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2019, 14, 423–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Employment Trajectory Type | Description | Proportion in Baseline Sample (N = 3782) | Proportion in Merged Sample T1 (N = 1487) | Proportion in Merged Sample T2 (N = 1252) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1. Conventional work life cycle | Dependent employees working persistently under formal, full-time, and stable employment conditions, who contribute continuously to social security. | 44.0 | 43.2 | 43.6 |

| Type 2. Out of the labor force | Includes individuals who remain inactive, unemployed, or are looking for a job during the whole period of interest, and who consequently did not contribute to social security at all. | 31.4 | 33.8 | 31.6 |

| Type 3. Full-time self-employed not contributing | Includes self-employed workers who do not contribute to social security at all (as expected, as they were not obliged to) and who have always been self-employed or switched to self-employment after a brief stint as dependent employees (generally after age 35). | 11.2 | 9.6 | 10.5 |

| Type 4. Wage-earners not contributing | Comprises dependent employees who do not contribute to social security, among which about a third start contributing toward the end of their careers. | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5.4 |

| Type 5. Full-time self-employed contributing | Groups the full-time self-employed who contribute to social security from the beginning of their careers. | 3.8 | 3.9 | 4.0 |

| Type 6. Part-time self-employed not contributing | Includes part-time self-employed workers who do not contribute to social security, among which some move to full-time positions in the late period of their working life. | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| Type 7. Part-time wage-earners contributing | Includes part-time dependent employees who contribute to social security, among which a small group from age 50 onwards start to move to full-time jobs. | 1.9 | 1.7 | 2.5 |

| Before Pandemic Onset | After Pandemic Onset | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Wave T1 | Merged Sample T1 | Wave T2 | Merged Sample T2 |

| Continuous PHQ-9 scale (mean, SD) | 4.2 | 4.5 | 5.9 | 6.1 |

| Five-level PHQ-9 scale (%) | ||||

| 64.9 | 63.1 | 51.1 | 51.3 |

| 21.3 | 21.6 | 25.2 | 23.2 |

| 8.2 | 9.0 | 13.2 | 13.6 |

| 3.6 | 3.9 | 6.8 | 8.0 |

| 2.1 | 2.4 | 3.7 | 3.9 |

| Two-level PHQ-9 scale (%) | ||||

| 86.2 | 84.7 | 74.7 | 74.5 |

| 13.8 | 15.3 | 25.3 | 25.5 |

| Gender (%) | ||||

| 43.1 | 42.3 | 43.3 | 43.4 |

| 56.9 | 57.7 | 56.7 | 56.6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cabib, I.; Budnevich-Portales, C.; Azar, A. Adulthood Employment Trajectories and Later Life Mental Health before and after the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13936. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113936

Cabib I, Budnevich-Portales C, Azar A. Adulthood Employment Trajectories and Later Life Mental Health before and after the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):13936. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113936

Chicago/Turabian StyleCabib, Ignacio, Carlos Budnevich-Portales, and Ariel Azar. 2022. "Adulthood Employment Trajectories and Later Life Mental Health before and after the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 13936. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113936

APA StyleCabib, I., Budnevich-Portales, C., & Azar, A. (2022). Adulthood Employment Trajectories and Later Life Mental Health before and after the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 13936. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113936