Infant Age Moderates Associations between Infant Temperament and Maternal Technology Use during Infant Feeding and Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics Questionnaire

2.2.2. Infant Behavior Questionnaire—Very Short Form

2.2.3. Maternal Distraction Questionnaire

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Associations between Maternal Tech Use and Infant Temperament

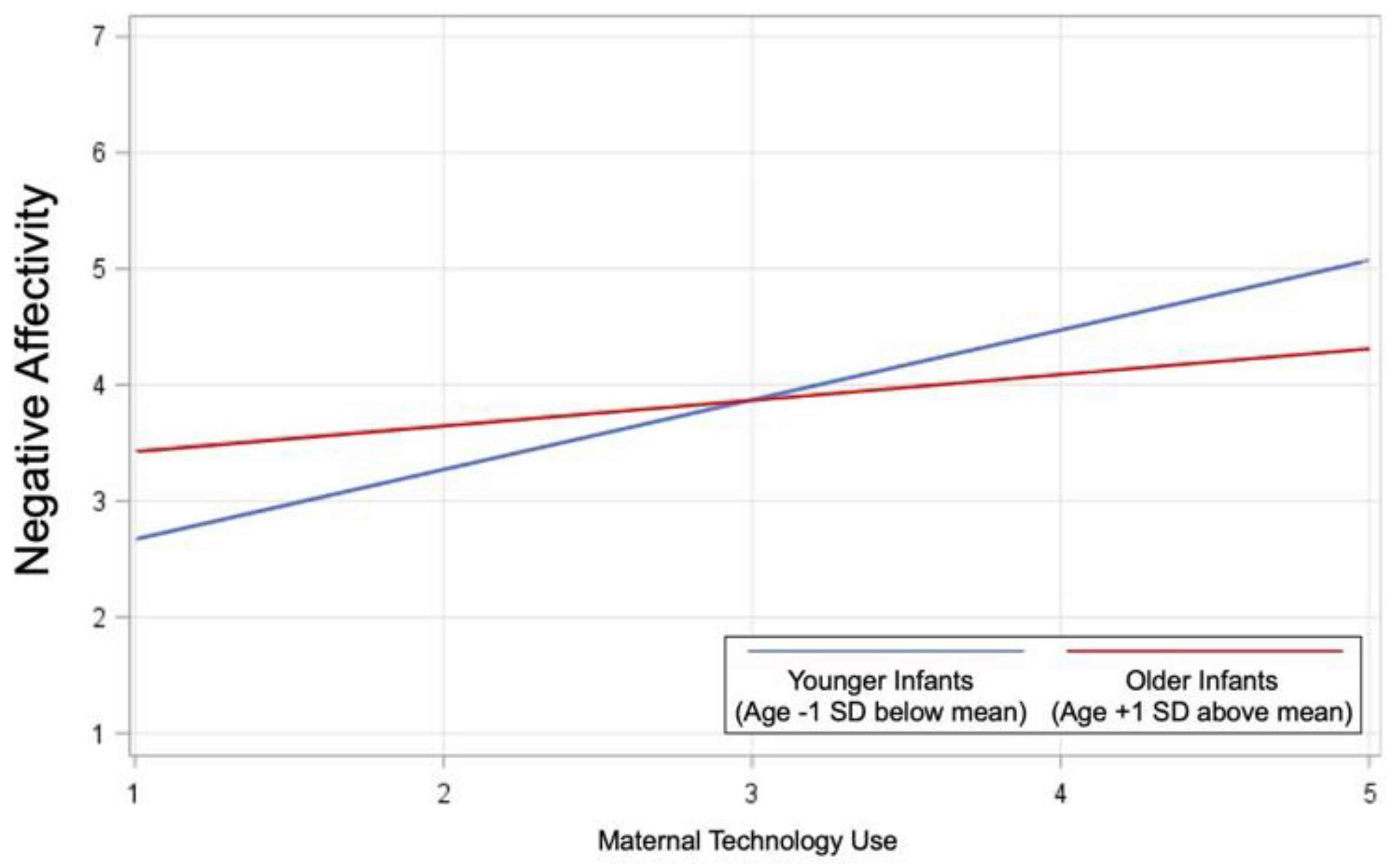

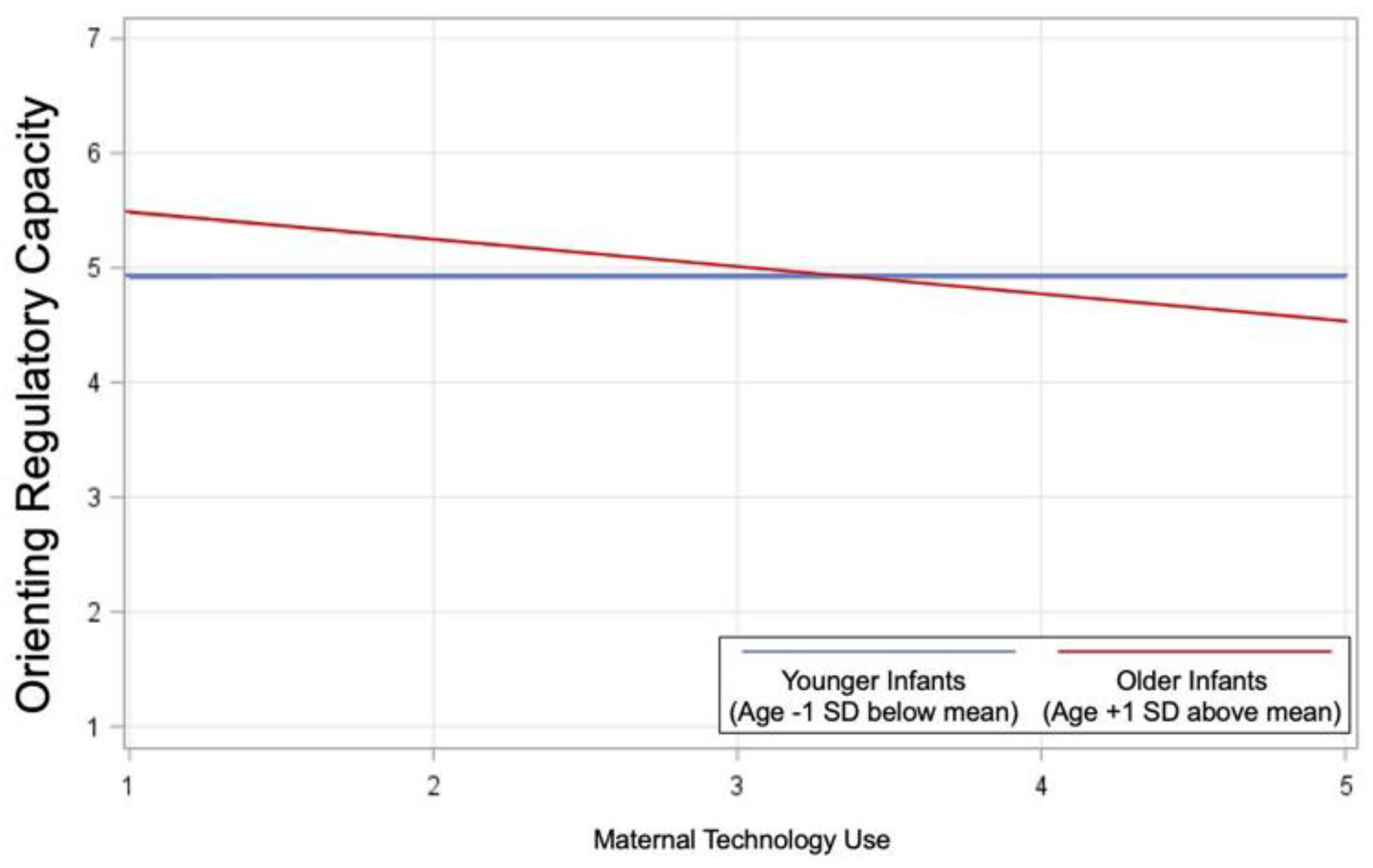

3.3. Infant Age Moderates Associations between Maternal Tech Use and Infant Temperament

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pew Research Center. Smartphone Ownership Is Growing Rapidly around the World, but Not Always Equally. 2019. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/02/05/smartphone-ownership-is-growing-rapidly-around-the-world-but-not-always-equally/ (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Pew Research Center. About Three-in-Ten U.S. Adults Say They Are ‘Almost Constantly’ Online. 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/03/26/about-three-in-ten-u-s-adults-say-they-are-almost-constantly-online/ (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Wartella, E.; Rideout, V.; Lauricella, A. Parenting in the Age of Digital Technology. 2014. Available online: http://cmhd.northwestern.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ParentingAgeDigitalTechnology.REVISED.FINAL_.2014.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Pew Research Center. Parenting Children in the Age of Screens. 2020. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/07/28/parenting-children-in-the-age-of-screens/ (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Ventura, A.K.; Teitelbaum, S. Maternal Distraction During Breast- and Bottle Feeding Among WIC and non-WIC Mothers. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49 (Suppl. 2), S169–S176.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, A.K.; Hupp, M.; Gutierrez, S.A.; Almeida, R. Development and validation of the Maternal Distraction Questionnaire. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radesky, J.S.; Kistin, C.; Eisenberg, S.; Gross, J.; Block, G.; Zuckerman, B.; Silverstein, M. Parent Perspectives on Their Mobile Technology Use: The Excitement and Exhaustion of Parenting While Connected. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2016, 37, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez Gutierrez, S.; Ventura, A.K. Associations between maternal technology use, perceptions of infant temperament, and indicators of mother-to-infant attachment quality. Early Hum. Dev. 2021, 154, 105305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, R.; Patterson, M.; Lundmark, V.; Kiesler, S.; Mukopadhyay, T.; Scherlis, W. Internet paradox. A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Am. Psychol. 1998, 5, 1017–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Coyne, S.M. Technology interference in the parenting of young children: Implications for mothers’ perceptions of coparenting. Soc. Sci. J. 2016, 53, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kildare, C.A. Infants’ perceptions of mothers’ phone use: Is mothers’ phone use generating the Still Face effect? In Education Psychology; University of North Texas: Denton, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Myruski, S.; Gulyayeva, O.; Birk, S.; Pérez-Edgar, K.; Buss, K.A.; Dennis-Tiwary, T.A. Digital disruption? Maternal mobile device use is related to infant social-emotional functioning. Dev. Sci. 2018, 21, e12610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, L.A.; Porter, C.L.; Coyne, S.M.; Essig, L.W.; Booth, M.; Keenan-Kroff, S.; Schvaneveldt, E. Infants’ response to a mobile phone modified still-face paradigm: Links to maternal behaviors and beliefs regarding technoference. Infancy 2020, 25, 571–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiff, C.J.; Lengua, L.J.; Zalewski, M. Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 14, 251–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Radesky, J.S. Technoference: Parent Distraction With Technology and Associations With Child Behavior Problems. Child Dev. 2018, 89, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, A.K.; Hernandez, A. Effects of opaque, weighted bottles on maternal sensitivity and infant intake. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, A.K.; Levy, J.; Sheeper, S. Maternal digital media use during infant feeding and the quality of feeding interactions. Appetite 2019, 143, 104415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gartstein, M.A.; Rothbart, M.K. Studying infant temperament via the Revised Infant Behavior Questionnaire. Infant Behav. Dev. 2003, 26, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, S.P.; Helbig, A.L.; Gartstein, M.A.; Rothbart, M.K.; Leerkes, E. Development and Assessment of Short and Very Short Forms of the Infant Behavior Questionnaire–Revised. J. Pers. Assess. 2013, 96, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golen, R.P.; Ventura, A.K. What are mothers doing while bottle-feeding their infants? Exploring the prevalence of maternal distraction during bottle-feeding interactions. Early Hum. Dev. 2015, 91, 787–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwarun, L.; Hall, A. What’s going on? Age, distraction, and multitasking during online survey taking. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 41, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.A.; Porter, C.L. The emergence of mother–infant co-regulation during the first year: Links to infants’ developmental status and attachment. Infant Behav. Dev. 2009, 32, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golen, R.; Ventura, A.K. Mindless feeding: Is maternal distraction during bottle-feeding associated with overfeeding? Appetite 2015, 91, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduor, E.; Neustaedter, C.; Odom, W.; Tang, A.; Moallem, N.; Tory, M.; Irani, P. The Frustrations and Benefits of Mobile Device Usage in the Home when Co-Present with Family Members. In Proceedings of the DIS ‘16: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 4–8 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ante-Contreras, D. Distracted Parenting: How social media affects parent-child attachment. In Social Work; California State University: San Bernardino, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tanimura, M.; Okuma, K.; Kyoshima, K. Television Viewing, Reduced Parental Utterance, and Delayed Speech Development in Infants and Young Children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 618–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.E.; Pempek, T.A.; Kirkorian, H.L.; Lund, A.F.; Anderson, D.R. The Effects of Background Television on the Toy Play Behavior of Very Young Children. Child Dev. 2008, 79, 1137–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkorian, H.L.; Pempek, T.A.; Murphy, L.A.; Schmidt, M.E.; Anderson, D.R. The Impact of Background Television on Parent-Child Interaction. Child Dev. 2009, 80, 1350–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothstein, T.M. The presence of smartphones and their impact on the quality of parent-child interactions. In Interdisciplinary Studies; California State University: Stanislaus, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | % (n) or Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Infants | |

| Age in weeks, mean (SD) | 16.2 (6.2) |

| Sex, % (n) female | 52.4 (196) |

| Mothers | |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 31.5 (4.5) |

| Education level | |

| Did not complete high school | 1.6 (6) |

| High-school degree | 9.6 (36) |

| Some college or vocational degree | 42.5 (159) |

| Bachelors or graduate degree | 46.3 (173) |

| Marital status, % (n) married | 70.8 (264) |

| Parity, % (n) primiparous | 34.1 (127) |

| Annual family income level | |

| <15,000 USD/year | 5.6 (21) |

| 15,000–<35,000 USD/year | 21.4 (80) |

| 35,000–<75,000 USD/year | 41.2 (154) |

| >75,000 USD/year | 30.2 (113) |

| Not reported | 1.6 (6) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic, White | 75.1 (281) |

| Non-Hispanic, Black | 7.5 (28) |

| Hispanic, any race | 10.4 (39) |

| Asian | 6.1 (23) |

| Not reported | 0.8 (3) |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Affectivity | Orienting/Regulatory Capacity | Positive Affectivity/ Surgency | |||||||

| Estimate | SE | p-Value | Estimate | SE | p-Value | Estimate | SE | p-Value | |

| Intercept | 3.19 | 0.49 | <0.001 | 5.22 | 0.39 | <0.001 | 3.64 | 0.51 | <0.001 |

| Mother’s age | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.93 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.14 |

| Mother’s education level | |||||||||

| Did not complete high school | −0.19 | 0.47 | 0.68 | −0.31 | 0.37 | 0.40 | −0.45 | 0.49 | 0.36 |

| High school degree | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.47 | −0.04 | 0.14 | 0.78 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.99 |

| Some college or vocational degree | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.26 | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.41 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.62 |

| Bachelors or graduate degree | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Not married | −0.23 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.32 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.21 |

| Married | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - |

| Parity, % (n) primiparous | |||||||||

| Multiparous | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.72 | −0.05 | 0.08 | 0.52 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.64 |

| Primiparous | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - |

| Annual family income level | |||||||||

| <15,000 USD/year | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.54 | −0.09 | 0.25 | 0.72 |

| 15,000–<35,000 USD/year | −0.01 | 0.15 | 0.99 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.88 |

| 35,000–<75,000 USD/year | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.04 |

| >75,000 USD/year | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic, White | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - |

| Non-Hispanic, Black | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.41 |

| Hispanic, any race | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.95 | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.02 |

| Asian | 0.34 | 0.20 | 0.08 | −0.34 | 0.16 | 0.03 | −0.24 | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| Infant age | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Maternal technology use | 0.40 | 0.07 | <0.001 | −0.13 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.62 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Affectivity | Orienting/Regulatory Capacity | Positive Affectivity/Surgency | |||||||

| Estimate | SE | p-Value | Estimate | SE | p-Value | Estimate | SE | p-Value | |

| Intercept | 1.81 | 0.71 | 0.01 | 4.36 | 0.56 | <0.001 | 2.56 | 0.74 | 0.01 |

| Mother’s age | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.86 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.12 |

| Mother’s education level | |||||||||

| Did not complete high school | −0.14 | 0.46 | 0.77 | −0.27 | 0.37 | 0.46 | −0.40 | 0.48 | 0.41 |

| High school degree | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.54 | −0.05 | 0.14 | 0.71 | −0.01 | 0.18 | 0.94 |

| Some college or vocational degree | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.15 | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.56 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.47 |

| Bachelors or graduate degree | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Not married | −0.22 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.18 |

| Married | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - |

| Parity, % (n) primiparous | |||||||||

| Multiparous | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.70 | −0.05 | 0.08 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.63 |

| Primiparous | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - |

| Annual family income level | |||||||||

| <15,000 USD/year | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.56 | −0.10 | 0.25 | 0.70 |

| 15,000–<35,000 USD/year | −0.04 | 0.15 | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.50 | −0.00 | 0.15 | 0.98 |

| 35,000–<75,000 USD/year | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| >75,000 USD/year | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic, White | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - |

| Non-Hispanic, Black | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.48 |

| Hispanic, any race | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.97 | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.02 |

| Asian | 0.35 | 0.20 | 0.08 | −0.33 | 0.16 | 0.03 | −0.23 | 0.20 | 0.25 |

| Infant age | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.001 |

| Maternal technology use | 0.91 | 0.20 | <0.001 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0.21 | 0.04 |

| Infant age × maternal technology use | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Davis, M.I.; Delfosse, C.M.; Ventura, A.K. Infant Age Moderates Associations between Infant Temperament and Maternal Technology Use during Infant Feeding and Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912858

Davis MI, Delfosse CM, Ventura AK. Infant Age Moderates Associations between Infant Temperament and Maternal Technology Use during Infant Feeding and Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912858

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavis, Maya I., Camille M. Delfosse, and Alison K. Ventura. 2022. "Infant Age Moderates Associations between Infant Temperament and Maternal Technology Use during Infant Feeding and Care" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912858

APA StyleDavis, M. I., Delfosse, C. M., & Ventura, A. K. (2022). Infant Age Moderates Associations between Infant Temperament and Maternal Technology Use during Infant Feeding and Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912858