“We Need Health for All”: Mental Health and Barriers to Care among Latinxs in California and Connecticut

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Data on Latinx Immigrant Health Needs and Assets

2.1.1. Sampling and Eligibility Criteria

2.1.2. Anxiety

2.1.3. Socio-Demographic Factors

2.1.4. Mental Health Services Access

2.1.5. Experiences of Discrimination

2.1.6. Reported and Perceived Barriers to Mental Health Services

2.2. Ethnographic Vignettes

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Research Question 1: What Factors Influence Mental Health among Latinx (im)migrant Community Members?

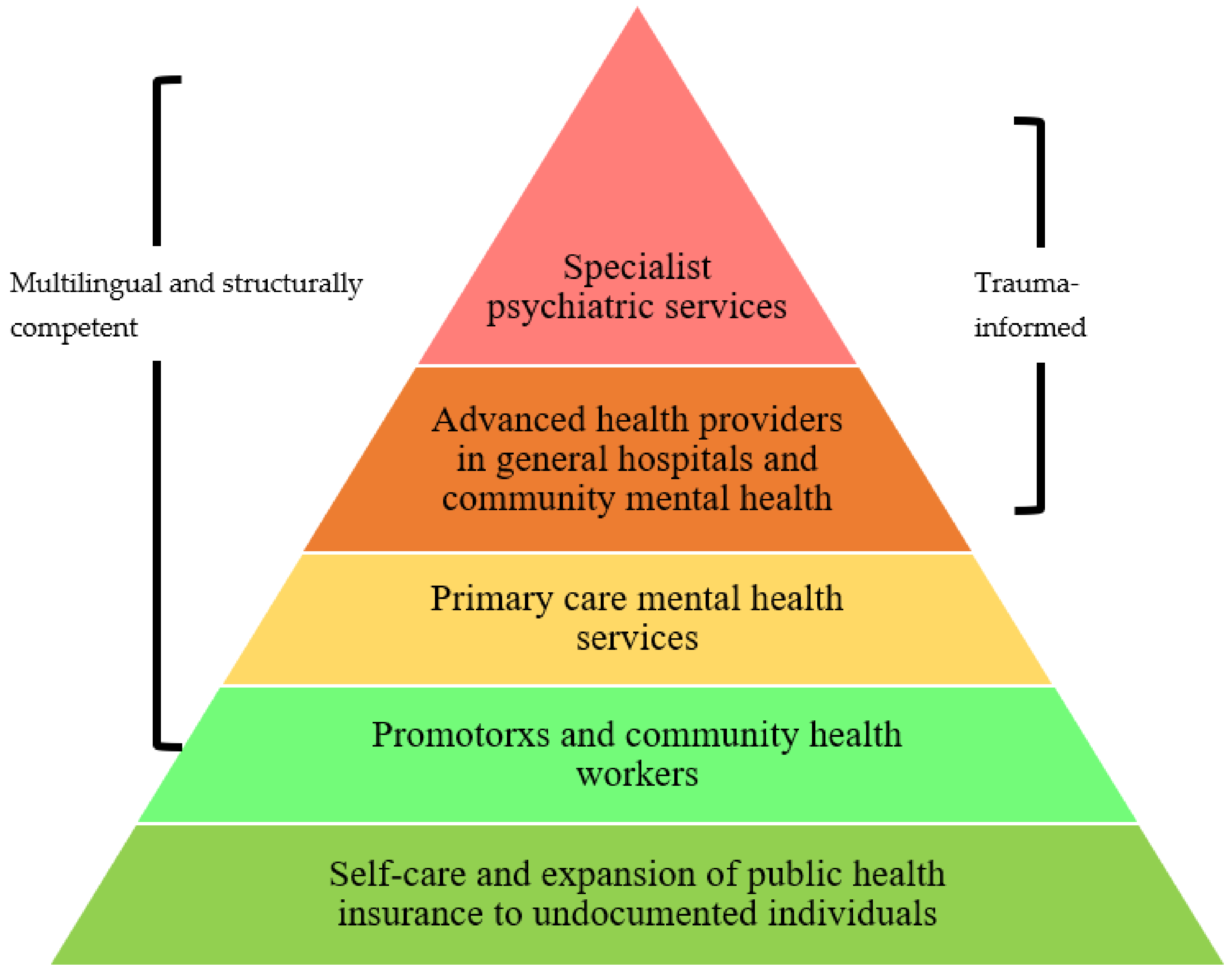

3.2. Research Question 2: How Can Services Be Effectively Improved to Meet these Factors and Barriers?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pew Research Center. A Brief Statistical Portrait of U.S Hispanics. 2022. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/06/14/a-brief-statistical-portrait-of-u-s-hispanics/ (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Vespa, J.; Medina, L.; Armstrong, D.M. Demographic Turning Points for the United States: Population Projections for 2020 to 2060; Current Population Reports; U.S. Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 25–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Noe-Bustamente, L.; Flores, A. Facts on Latinos in America. Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project. 2019. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/fact-sheet/latinos-in-the-u-s-fact-sheet/ (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Ayalew, B.; Dawson-Hahn, E.; Cholera, R.; Falusi, O.; Haro, T.M.; Montoya-Williams, D.; Linton, J.M. The Health of Children in Immigrant Families: Key Drivers and Research Gaps Through an Equity Lens. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 21, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdahl, T.A.; Torres Stone, R.A. Examining Latino Differences in Mental Healthcare Use: The Roles of Acculturation and Attitudes towards Healthcare. Community Ment. Health J. 2009, 45, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, W.A.; Kolody, B.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Catalano, R. Gaps in Service Utilization by Mexican Americans with Mental Health Problems. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegria, M.; Canino, G.; Ríos, R.; Vera, M.; Calderón, J.; Rusch, D.; Ortega, A.N. Mental Health Care for Latinos: Inequalities in Use of Specialty Mental Health Services among Latinos, African Americans, and Non-Latino Whites. Psychiatr. Serv. 2002, 53, 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverluk, T. The Changing Geography of US Hispanics, 1850–1990. J. Geogr. 1997, 96, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nostrand, R.L. The Hispano Homeland in 1900. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1980, 70, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.A.; Paris, M.; Añez, L.M. CAMINO: Integrating Context in the Mental Health Assessment of Immigrant Latinos. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2017, 48, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Hispanics, Latino or Spanish Origin or Descent; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Association: Rockville, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lisotto, M.J. Mental Health Disparities: Hispanics and Latinos; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alegria, M.; Canino, G.; Shrout, P.E.; Woo, M.; Duan, N.; Vila, D.; Torres, M.; Chen, C.; Meng, X.-L. Prevalence of Mental Illness in Immigrant and Non-Immigrant U.S. Latino Groups. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Garcia, D.; Bates, L.M. Latino Health Paradoxes: Empirical Evidence, Explanations, Future Research, and Implications. In Latinas/os in the United States: Changing the Face of America; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kann, L.; McManus, T.; Harris, W.A.; Shanklin, S.L.; Flint, K.H.; Queen, B.; Lowry, R.; Chyen, D.; Whittle, L.; Thornton, J.; et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2017. Surveill. Summ. 2018, 67, 1–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Behavioral Health Barometer: United States, 2015; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2015; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, T.; Keller, A.S.; Rasmussen, A. Effects of Post-Migration Factors on PTSD Outcomes among Immigrant Survivors of Political Violence. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2013, 15, 890–897. [Google Scholar]

- Perreira, K.M.; Ornelas, I. Painful Passages: Traumatic Experiences and Post-Traumatic Stress among US Immigrant Latino Adolescents and Their Primary Caregivers. Int. Migr. Rev. 2013, 47, 976–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, W.A. Crossing Mexico: Structural Violence and the Commodification of Undocumented Central American Migrants. Am. Ethnol. 2013, 40, 764–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, W.A. Lives in Transit: Violence and Intimacy on the Migrant Journey; California Series in Public Anthropology; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2018; Volume 42. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, E.; Decker, M.R.; Silverman, J.G.; Raj, A. Migration, Sexual Exploitation, and Women’s Health: A Case Report from a Community Health Center. Violence Against Women 2007, 13, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, C.; Zimmerman, C. Violence against Women: Global Scope and Magnitude. Lancet 2002, 359, 1232–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleaveland, C.; Frankenfeld, C. “They Kill People Over Nothing”: An Exploratory Study of Latina Immigrant Trauma. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2020, 46, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, L.R.; Noroña, C.R.; Porche, M.V.; Tillman, C.; Patil, P.A.; Wang, Y.; Markle, S.L.; Alegría, M. Trauma, Immigration, and Sexual Health among Latina Women: Implications for Maternal–Child Well-being and Reproductive Justice. Infant Ment. Health J. 2019, 40, 640–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltman, S.; Hurtado de Mendoza, A.; Serrano, A.; Gonzales, F.A. A Mental Health Intervention Strategy for Low-Income, Trauma-Exposed Latina Immigrants in Primary Care: A Preliminary Study. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2016, 86, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdeña, J.P.; Rivera, L.M.; Spak, J.M. Intergenerational Trauma in Latinxs: A Scoping Review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 270, 113662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treisman, R. NPR. Whistleblower Alleges “Medical Neglect”, Questionable Hysterectomies of ICE Detainees. 2020. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2020/09/16/913398383/whistleblower-alleges-medical-neglect-questionable-hysterectomies-of-ice-detaine (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Cariello, A.N.; Perrin, P.B.; Williams, C.D.; Espinoza, G.A.; Morlett-Paredes, A.; Moreno, O.A.; Trujillo, M.A. Moderating Influence of Enculturation on the Relations between Minority Stressors and Physical Health via Anxiety in Latinx Immigrants. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minority Psychol. 2020, 26, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, A.R.I.; Haws, J.K.; Acosta, L.M.; Acosta Canchila, M.N.; Carlo, G.; Grant, K.M.; Ramos, A.K. Combinatorial Effects of Discrimination, Legal Status Fears, Adverse Childhood Experiences, and Harsh Working Conditions among Latino Migrant Farmworkers: Testing Learned Helplessness Hypotheses. J. Lat. Psychol. 2020, 8, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.G.T.T.; Lee, R.M.; Burgess, D.J. Perceived Discrimination and Substance Use in Hispanic/Latino, African-Born Black, and Southeast Asian Immigrants. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minority Psychol. 2010, 16, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekteshi, V.; Kang, S. Contextualizing Acculturative Stress among Latino Immigrants in the United States: A Systematic Review. Ethn. Health 2020, 25, 897–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.S.-H.; Kaushal, N. Health and Mental Health Effects of Local Immigration Enforcement. Int. Migr. Rev. 2019, 53, 970–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, O.; Wu, E.; Sandfort, T.; Dodge, B.; Carballo-Dieguez, A.; Pinto, R.; Rhodes, S.D.; Moya, E.; Chavez-Baray, S. Evaluating the Impact of Immigration Policies on Health Status Among Undocumented Immigrants: A Systematic Review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 947–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, D.; Hernandez, G.; Porchas, F.; Castillo, J.; Nguyen, V.; Perez González, R. Immigration Policies and Mental Health: Examining the Relationship between Immigration Enforcement and Depression, Anxiety, and Stress among Latino Immigrants. J. Ethn. Cult. Divers. Soc. Work. Innov. Theory Res. Pract. 2020, 29, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcini, L.M.; Renzaho, A.M.N.; Molina, M.; Ayala, G.X. Health-Related Quality of Life among Mexican-Origin Latinos: The Role of Immigration Legal Status. Ethn. Health 2018, 23, 566–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, E.D.; Sanchez, G.R.; Juárez, M. Fear by Association: Perceptions of Anti-Immigrant Policy and Health Outcomes. J. Health Politics Policy Law 2017, 42, 459–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Cinisomo, S.; Fujimoto, E.M.; Oksas, C.; Jian, Y.; Gharheeb, A. Pilot Study Exploring Migration Experiences and Perinatal Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Immigrant Latinas. Matern. Child Health J. 2019, 23, 1627–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, S.D.; Mann, L.; Simán, F.M.; Song, E.; Alonzo, J.; Downs, M.; Lawlor, E.; Martinez, O.; Sun, C.J.; O’Brien, M.C. The Impact of Local Immigration Enforcement Policies on the Health of Immigrant Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzelius, E.; Baum, A. The Mental Health of Hispanic/Latino Americans Following National Immigration Policy Changes: United States, 2014–2018. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 1786–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, K.; Chu, J.; Leung, C.; Marra, R.; Pirie, A.; Brahimi, M.; English, M.; Beckmann, J.; Acevedo-Garcia, D.; Marlin, R.P. The Impact of Immigration and Customs Enforcement on Immigrant Health: Perceptions of Immigrants in Everett, Massachusetts, USA. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, W.D.; Kruger, D.J.; Delva, J.; Llanes, M.; Ledón, C.; Waller, A.; Harner, M.; Martinez, R.; Sanders, L.; Harner, M.; et al. Health Implications of an Immigration Raid: Findings from a Latino Community in the Midwestern United States. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2017, 19, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chishti, M.; Pierce, S.; Bolter, J. The Obama Record on Deportations: Deporter in Chief or Not? Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/obama-record-deportations-deporter-chief-or-not (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- American Immigration Council Summary of Executive Order “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States”. Available online: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/immigration-interior-enforcement-executive-order (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- Ramos-Sánchez, L.; Pietrantonio, K.; Llamas, J. The Psychological Impact of Immigration Status on Undocumented Latinx Women: Recommendations for Mental Health Providers. Peace Confl. 2020, 26, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trump, D.J. Executive Order: Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/01/30/2017-02102/enhancing-public-safety-in-the-interior-of-the-united-states (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- Immigrant Legal Resource Center National Map of 287(g) Agreements. Available online: https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/PKrP1/4/ (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Temporary Protected Status Designated Country: Nicaragua. Available online: https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/temporary-protected-status/temporary-protected-status-designated-country-nicaragua (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- Miller, M.E. Washington Post. ‘They Just Took Them?’ Frantic Parents Separated from Their Kids Fill Courts on the Border. 2018. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/they-just-took-them-frantic-parents-separated-from-their-kids-fill-courts-on-the-border/2018/06/09/e3f5170c-6aa9-11e8-bea7-c8eb28bc52b1_story.html (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- The Independent “Words Matter”: Trump Accused of Fuelling Attacks on Hispanics as Violent Hate Crimes Hit 16-Year High. 2019. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/hate-crimes-racism-violence-us-fbi-hispanic-a9200671.html (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Bourgois, P.; Holmes, S.M.; Sue, K.; Quesada, J. Structural Vulnerability: Operationalizing the Concept to Address Health Disparities in Clinical Care. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2017, 92, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasich, J. Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996. Contemp. Sociol. 1997, 26, 409–415. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, E.; Kinoshita, S. An Overview of Public Charge and Benefits; Immigrant Legal Resource Center: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Artiga, S.; Diaz, M. Kaiser Family Foundation. Health Coverage and Care of Undocumented Immigrants. 2019. Available online: https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/health-coverage-and-care-of-undocumented-immigrants/ (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Bucay-Harari, L.; Page, K.R.; Krawczyk, N.; Robles, Y.P.; Castillo-Salgado, C. Mental Health Needs of an Emerging Latino Community. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2020, 47, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.A.; Cha, A.E.; Martinez, M.E.; Terlizzi, E.P. Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2019; National Center for Health Statistics: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Surgeon General; Center for Mental Health Services; National Institute of Mental Health. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General; Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, J.L.; Miller, G.E.; Kirby, J.B. Explaining Racial and Ethnic Differences in Children’s Use of Stimulant Medications. Med. Care 2007, 45, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, J.B.; Hudson, J.; Miller, G.E. Explaining Racial and Ethnic Differences in Antidepressant Use Among Adolescents. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2010, 67, 342–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, F.H.; Bogart, L.M.; Klein, D.J.; Wagner, G.J.; Chen, Y.-T. Medical Mistrust as a Key Mediator in the Association between Perceived Discrimination and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy among HIV-Positive Latino Men. J. Behav. Med. 2017, 40, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cevallos, D.F.; Harvey, S.M.; Warren, J.T. Medical Mistrust, Perceived Discrimination, and Satisfaction With Health Care Among Young-Adult Rural Latinos. J. Rural. Health 2014, 30, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cevallos, D.F.; Flórez, K.R.; Derose, K.P. Examining the Association between Religiosity and Medical Mistrust among Churchgoing Latinos in Long Beach, CA. Transl. Behav. Med. 2019, 11, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czeisler, M.É.; Marynak, K.; Klarke, K.E.N.; Salah, Z.; Shakya, I.; Thierry, J.M.; Ali, N.; McMillan, H.; Wiley, J.; Weaver, M.D.; et al. Delay or Avoidance of Medical Care Because of COVID-19–Related Concerns. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2020, 69, 1250–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcini, L.M.; Domenech Rodríguez, M.M.; Mercado, A.; Paris, M. A Tale of Two Crises: The Compounded Effect of COVID-19 and Anti-Immigration Policy in the United States. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcini, L.M.; Murray, K.E.; Zhou, A.; Klonoff, E.A.; Myers, M.G.; Elder, J.P. Mental Health of Undocumented Immigrant Adults in the United States: A Systematic Review of Methodology and Findings. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2016, 14, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, T.M.; Ross DeCamp, L.; Platt, R.E.; Shah, H.; Johnson, S.B.; Sibinga, E.M.S.; Polk, S. Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Latino Children in Immigrant Families. Clin. Pediatr. 2017, 56, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Loi, C.X.A.; Chiriboga, D.A.; Jang, Y.; Parmelee, P.; Allen, R.S. Limited English Proficiency as a Barrier to Mental Health Service Use: A Study of Latino and Asian Immigrants with Psychiatric Disorders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 45, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmins, C.L. The Impact of Language Barriers on the Health Care of Latinos in the United States: A Review of the Literature and Guidelines for Practice. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2002, 47, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, K.; Jenicek, G.; Gerdes, M. Overcoming Language Barriers in Mental and Behavioral Health Care for Children and Adolescents—Policies and Priorities. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 511–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegría, M.; Álvarez, K.; DiMarzio, K. Immigration and Mental Health. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2017, 4, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, H.M.; Rodriguez, M.A.; Quiroga, S.S.; Flores-Ortiz, Y.G. Barriers to Health Care for Abused Latina and Asian Immigrant Women. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2000, 11, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, J.S.; Soulen, G.; Davila, C.B.; Cartmell, K. Access to Health Care for Uninsured Latina Immigrants in South Carolina. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, M.M. Yakama Rising: Indigenous Cultural Revitalization, Activism, and Healing; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-8165-9921-9. [Google Scholar]

- Jolivétte, A.J. Indian Blood: HIV and Colonial Trauma in San Francisco’s Two-Spirit Community; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-295-99849-7. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Lonebear, D. Building a Data Revolution in Indian Country. In Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Toward an Agenda; Kukutai, T., Taylor, J., Eds.; Australian National University Press: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2016; pp. 253–272. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.T. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2nd ed.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-84813-950-3. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, M.; Boj Lopez, F.; Urrieta, L. Special Issue: Critical Latinx Indigeneities. Lat. Stud. 2017, 15, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.; Perez, C.A.; Mejia, M.C. Immigrants in California; Public Policy Institute of California: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- American Immigration Council Immigrants in Connecticut; American Immigration Council: 2015. Available online: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/immigrants-connecticut (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Bloss, W. Escalating U.S. Police Surveillance after 9/11: An Examination of Causes and Effects. Surveill. Soc. 2007, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado-de-Mendoza, A.; Gonzales, F.A.; Serrano, A.; Kaltman, S. Social Isolation and Perceived Barriers to Establishing Social Networks Among Latina Immigrants. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2014, 53, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, M.; Ebarb, A.; Pytalski, S.; Roubideaux, Y. Disaggregating American Indian & Alaska Native Data: A Review of Literature; National Congress of American Indians: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Potochnick, S.R.; Perreira, K.M. Depression and Anxiety among First-Generation Immigrant Latino Youth: Key Correlates and Implications for Future Research. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2010, 198, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, A.; Joscelyne, A.; Granski, M.; Rosenfeld, B. Pre-Migration Trauma Exposure and Mental Health Functioning among Central American Migrants Arriving at the US Border. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0168692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Research: Biosocial Dynamics of Intergenerational Transmission of Stress. Available online: https://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward?AWD_ID=1918769&HistoricalAwards=false (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Jessica, P. The Wenner-Gren Foundation Cerdena. Available online: https://wennergren.org/grantee/jessica-cerdena/ (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- Kofman, J. Trint. 2020. Available online: https://trint.com/about-us (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Geertz, C. Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture. In The Cultural Geography Reader; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Jolivétte, A.J. (Ed.) Research Justice: Methodologies for Social Change, 1st ed.; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, P.H. Toward a New Vision: Race, Class, and Gender as Categories of Analysis and Connection. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/ (accessed on 9 January 2020).

- Derr, A.S. Mental Health Service Use among Immigrants in the United States: A Systematic Review. Psychiatr. Serv. 2016, 67, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, Y.; Fenning, P. Toward Understanding Mental Health Concerns for the Latinx Immigrant Student: A Review of the Literature. Urban Educ. 2017, 56, 959–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, R.G.; Suárez-Orozco, C.; Dedios-Sanguineti, M.C. No Place to Belong: Contextualizing Concepts of Mental Health among Undocumented Immigrant Youth in the United States. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 1174–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorter, J.W.; Stewart, D.; Smith, M.W.; King, G.; Wright, M.; Nguyen, T.; Freeman, M.; Swinton, M. Pathways toward Positive Psychosocial Outcomes and Mental Health for Youth with Disabilities: A Knowledge Synthesis of Developmental Trajectories. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2014, 33, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, S.; Campbell, L.R.; Herrick, C.A. Factors Affecting Use of the Mental Health System by Rural Children. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2002, 23, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iturralde, E.; Chi, F.W.; Grant, R.W.; Weisner, C.; Van Dyke, L.; Pruzansky, A.; Bui, S.; Madvig, P.; Pearl, R.; Sterling, S.A. Association of Anxiety with High-Cost Health Care Use Among Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes. Dia Care 2019, 42, 1669–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbona, C.; Olvera, N.; Rodriguez, N.; Hagan, J.; Linares, A.; Wiesner, M. Acculturative Stress among Documented and Undocumented Latino Immigrants in the United States. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2010, 32, 362–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, S. Latinos, Acculturation, and Acculturative Stress: A Dimensional Concept Analysis. Policy Politics Nurs. Pract. 2007, 8, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovey, J.D.; King, C.A. Acculturative Stress, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation among Immigrant and Second-Generation Latino Adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1996, 35, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.; Driscoll, M.W.; Voell, M. Discrimination, Acculturation, Acculturative Stress, and Latino Psychological Distress: A Moderated Mediational Model. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minority Psychol. 2012, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willen, S.S. Do “Illegal” Im/Migrants Have a Right to Health? Engaging Ethical Theory as Social Practice at a Tel Aviv Open Clinic. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2011, 25, 303–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willen, S.S. How Is Health-Related “Deservingness” Reckoned? Perspectives from Unauthorized Im/Migrants in Tel Aviv. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, S.S. Agency, Initiative, and Obstacles to Health Among Indigenous Immigrant Women from Oaxaca, Mexico. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2006, 18, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, D.; Lee, R.; Tran, A.; van Ryn, M. Effects of Perceived Discrimination on Mental Health and Mental Health Services Utilization Among Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Persons. J. LGBT Health Res. 2007, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, R.M.; Ayala, G.; Bein, E.; Henne, J.; Marin, B.V. The Impact of Homophobia, Poverty, and Racism on the Mental Health of Gay and Bisexual Latino Men: Findings from 3 US Cities. Am. J. Public Health 2001, 91, 927–932. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zea, M.C.; Reisen, C.A.; Poppen, P.J. Psychological Well-Being among Latino Lesbians and Gay Men. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minority Psychol. 1999, 5, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mio, J.S.; Iwamasa, G.Y. Culturally Diverse Mental Health: The Challenges of Research and Resistance; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-317-79475-2. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Improving Health Systems and Services for Mental Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Central CA Sample | Southern CT Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Response Categories | n | % | n | % |

| Gender | Women | 123 | 82.0 | 65 | 100.0 |

| Men | 14 | 9.3 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Not Listed | 13 | 8.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Indigeneity | Not Indigenous | 125 | 83.3 | 59 | 90.8 |

| Indigenous | 25 | 16.7 | 6 | 9.2 | |

| Country of Origin | Belizean | 2 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Brazilian | 2 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Chicana/o/x | 5 | 3.9 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Chilean | 2 | 1.6 | 1 | 1.5 | |

| Colombian | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.5 | |

| Cuban | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Dominican | 1 | 0.8 | 7 | 10.8 | |

| Ecuadorian | 0 | 0.0 | 18 | 27.7 | |

| Guatemalan | 9 | 6.6 | 9 | 13.8 | |

| Honduran | 1 | 0.7 | 2 | 3.1 | |

| Jamaican | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.5 | |

| Mexican | 91 | 66.9 | 15 | 23.1 | |

| Mexican–American | 23 | 16.9 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Peruvian | 2 | 1.5 | 2 | 3.1 | |

| Puerto Rican | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 10.8 | |

| Salvadoran | 7 | 5.1 | 2 | 3.1 | |

| Categorical Variables | Response Categories | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility criteria | Outside advocate | 38 | 21.5 |

| Immigrant community members | 139 | 78.5 | |

| Language | English | 95 | 53.7 |

| Spanish | 82 | 46.3 | |

| Race | Other Race | 22 | 14.3 |

| Latina/o/x or Hispanic | 132 | 85.7 | |

| Indigeneity | Not Indigenous | 125 | 83.3 |

| Indigenous | 25 | 16.7 | |

| Insurance Coverage | No/Decline to State | 34 | 30.1 |

| Yes | 79 | 69.9 | |

| Continuous Variables | M | SD | |

| General anxiety disorder symptoms a | 1.91 | 0.77 | |

| Trust in biomedical healthcare b | 2.89 | 0.62 | |

| Trust in therapists b | 2.79 | 0.76 | |

| Mental health knowledge c | 3.35 | 1.32 | |

| Concern for mental health issues c | 3.57 | 1.44 | |

| Experiences of discrimination a | 0.47 | 0.90 | |

| Independent Variables | B | SE | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immigrant community member | −0.03 | 0.19 | −0.02 |

| Spanish-speaking | −0.18 | 0.18 | −0.12 |

| Latina/o/x or Hispanic | −0.43 | 0.24 | −0.19 |

| Indigenous | 0.29 | 0.20 | −14 |

| Insured | 0.47 ** | 0.17 | 0.29 |

| Trust in biomedical healthcare | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.09 |

| Trust in therapists | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| Mental health knowledge | −0.21 ** | 0.07 | −0.37 |

| Concern for mental health issues | 0.11 * | 0.06 | 0.22 |

| Experiences of discrimination | 0.19 * | 0.08 | 0.26 |

| Constant | 1.55 *** | 0.47 | |

| Model Summary | |||

| F (10, 80) | 3.87 *** | ||

| R2 | 0.326 | ||

| Barriers | Health Needs | Relevant Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Access | Preventative health services Accessibility Transportation Language support Remove fear and stigma Nutrition | “We need health4all. I am undocumented (DACA), and was accessing (student health insurance) but now that I’ve graduated I will lose coverage”. “Necesito más dinero para comida y medicina” a “Outreach is essential”. “Tener mas [sic] recurso y confiar en el sistema”. b |

| Cost | Free or low-cost services Affordable sliding scales Insurance coverage Childcare Affordable housing | “Mas recursos economicos [sic] para todos” c “Recognizing that emergency Medi-Cal and sliding scales are not equitable care.” “Ser mas [sic] considerados y flexibles ala hora de ayudarlos en cualquier problema ya sea de salud o de algun otro recurso que ocupen para mejorar su estilo de vida” d |

| Capacity | High-quality and consistent health services Mental health services Specialty doctors Health promotion and outreach | “More education, more promotion and easier access to services” “Ahora la salud mental no hay ayuda si no tienes papeles ahora la estan ofreciendo solo x lo del COVID-19, si no ni ofrecen ayuda psicológica” e “Proveyendo mas (sic) servicios y haciendo mas [sic] outreach para que la comunidad sepa de ellos, muchas veces si hay servicios pero la gente no esta (sic) informada y/o no saben que existen esos servicios” f |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Espinoza-Kulick, M.A.V.; Cerdeña, J.P. “We Need Health for All”: Mental Health and Barriers to Care among Latinxs in California and Connecticut. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912817

Espinoza-Kulick MAV, Cerdeña JP. “We Need Health for All”: Mental Health and Barriers to Care among Latinxs in California and Connecticut. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912817

Chicago/Turabian StyleEspinoza-Kulick, Mario Alberto Viveros, and Jessica P. Cerdeña. 2022. "“We Need Health for All”: Mental Health and Barriers to Care among Latinxs in California and Connecticut" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912817

APA StyleEspinoza-Kulick, M. A. V., & Cerdeña, J. P. (2022). “We Need Health for All”: Mental Health and Barriers to Care among Latinxs in California and Connecticut. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912817