1. Introduction

The root cause of the lagging process regarding the urban citizenship of the agricultural migrant population is considered to be the “umbilical cord” relationship between farmers and rural residential bases [

1]. With the continuous promotion of new types of urbanization, a large number of migrant agricultural workers are expected to flow into cities, with a total of 292.51 million migrant workers in China by 2021 [

2]. According to statistics, by the end of 2021, the urbanization rate of China’s resident population had reached 64.72%, but the urban household registration rate was only 46.7% [

3]. The current registered residence system in China divides the household registration into urban household registration and rural household registration according to the relationship of blood inheritance and geographical location. This urban–rural “amphibious” living pattern of rural laborers has created a dilemma, in which the rigid demand for urban land co-exists with the wasteful use of rural land [

4]. According to data from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, the rural labor force has been living in rural areas for more than 20 years. According to the data of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, the area of rural house bases is 168 million mu, accounting for 48.62% of the collective construction land area. According to the relevant data, there are 261 million migrant workers and their accompanying family members who have become permanent residents in urban areas, and the idle rate of rural residential bases is as high as 17.6% [

5]. This large number of unused rural residential bases not only leads to a waste of land resources and various safety hazards, but also seriously affects the improvement of the rural living environment and the promotion of rural urbanization [

6]. In order to resolve the dilemma of idle and inefficient use of residential bases, in 2004, the State Council already pointed out in the Central Document No. 28 that it advocates the moderate adjustment of rural construction land, and the moderate increase of urban construction land should be linked with the moderate reduction of rural construction land. In 2008, the State Council clearly put forward the policy of “urban-rural linkage increase/decrease” in the “Management Measures of Urban-Rural Construction Land Increase/Decrease Pilot”. In 2016, the State Council issued “Several Opinions on Deepening the Construction of a New Type of Urbanization” (No.8 Document of State Council [2016]), which pointed out that “exploring the mechanism of voluntary and compensated withdrawal of farmers’ rights to land contract, use homestead and collective income distribution”. In 2022, the No. 1 document of “the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the State Council on the key work of comprehensive promotion of rural revitalization in 2022” further emphasized “prudently promote the pilot reform of the rural homestead system, and standardize the registration of housing land as one of the homestead rights”. It points out the direction for regulating rural construction land, promoting the voluntary and compensated withdrawal of rural land rights and interests of the agricultural transfer population, and implementing the withdrawal mechanism of rural homestead in the context of citizenship. The newly amended Land Management Law in 2019 stipulates that the state will allow rural villagers who have settled in cities to withdraw from their residential bases voluntarily and be compensated, according to the law. However, the results of a large number of surveys regarding the willingness to withdraw from residential bases have shown that the percentage of farmers who settle in cities and are unwilling to withdraw from their residential bases is 50–70% [

7]. As the voluntary principle is the basis for the implementation of the homestead withdrawal system [

8], it is of great practical significance to study the influencing mechanisms of the decision to withdraw from residential bases by farmers who have settled in cities in depth, in order to scientifically design the mechanism for voluntary and paid withdrawal from residential bases, thus encouraging farmers who have settled in cities to withdraw from their residential bases voluntarily and steadily promoting the reform of the rural residential base system.

In the existing relevant literature, scholars have mainly focused on value perception [

9], risk expectation [

10], ownership [

11], local attachment [

12], and so on, and have explored the various influences on the willingness of urban farmers to withdraw from their residential bases. The decision to voluntarily withdraw from residential bases is based on a rational analysis of the trade-off between pros and cons; however, as there is no uniform standard for the judgment of pros and cons, this judgment may be highly subjective [

13]. The decision of farmers to voluntarily withdraw from their residential land is based on rational analysis, instinctive psychological factors (e.g., internal emotions, desires, and perceptions), and their external social environment [

14]. Therefore, in this study, we analyze the interactions between and influence of emotional, psychological, and social environment factors on the willingness of farmers in cities to withdraw from their homestead bases.

From the perspective of the armer’s own internal psychological factors, 55.98% of farmers subjectively believe that homestead bases are privately owned by the farmers [

4]. However, from the perspective of legal system, the ownership of rural homestead in China belongs to the collective, and farmers only have the right to use the homestead. This is because rural homestead assume a variety of functions, such as production, living, and emotional belonging, to which farmers assign higher value expectations [

15]. Withdrawal from the rural homestead is a major problem, which entails the loss of these functions and rights. Therefore, farmers will repeatedly make psychological trade-offs when withdrawing from their homesteads, which makes farmers have a strong sense of relative deprivation which, in turn, inhibits their homestead withdrawal behavior [

16]. The relative dispossession of farmers arises from their sense of dispossession. The sense of relative deprivation in farmers originates from a loss of functional dependence on the homestead, which also reflects their concerns regarding access to material resources, social relations, and development opportunities after losing the functional rights and interests carried by the homestead under the conditions of relatively institutionalized social inequality [

17].

An individual’s life situation is no longer confined to the private world but is increasingly influenced by the broader social context and social structure. In other words, the relative sense of deprivation produced by social comparison of individuals is not only related to their own conditions, but also, to some extent, is the result of the social environment. In terms of the factors that influence the willingness of farmers to withdraw from their homestead, the following two aspects are the most important.

First, the behavior of farmers will be influenced by external social environment factors (i.e., social trust). With the implementation of the rural revitalization strategy and the construction of rural civilization, the social trust among farmers has been enhanced. Social trust relationships reflect an individual’s rights and obligations to others or social organizations to honor the relationship. So, does the level of social trust affect the homestead withdrawal behavior of farmers? Does the level of social trust play a mediating role in the relative sense of deprivation on their willingness to withdraw from their homestead? Does the sense of relative deprivation lead to a decrease in trust in the government, which in turn has an impact on the willingness of rural residents to withdraw from their homestead? These questions are worth exploring in depth. Second, homestead withdrawal requires farmers to complete urban integration into a new place. Urban integration does not only involve economic integration, in terms of labor and employment, economic income, and living conditions but, more importantly, it involves a higher level of integration in social and psychological aspects. This is mainly reflected in the conceptual acceptance and recognition of urban culture, such as the customs, behavioral norms, and values in cities. This cultural and psychological urban integration status reflects the degree of attachment and psychological distance of urban farmers to the city and influences their behavior and decision making. Urban integration can lead to a positive interaction between individual development and social development. Therefore, in this paper, we incorporate urban integration into the considered analytical framework and explore the moderating effect of urban integration on the homestead withdrawal behavior of farmers.

Based on this, we conducted this study in order to clarify the logical ideas of rural home base withdrawal, analyze the factors that influence the decision of home base withdrawal behavior of interest subjects, and provide a scientific decision basis for promoting rural home base withdrawal and accelerating the process of transferring citizens of agricultural population in terms of policies, measures and paths, so as to design and develop an incentive mechanism for home base withdrawal of citizens of agricultural transfer population. We selected some urban migrants for empirical research. The urban migrant group studied in this paper refers to those who move from rural to urban areas for a long period of time, referred to as “rural migrants”. This concept breaks through the limitations of the concept of “migrant workers” used in earlier studies, based on the background of the urban–rural dual structure, and is consistent with the trend characteristics of the rural population moving to the city to work and live, in the context of accelerating the citizenship of the migrant agricultural population in the new urbanization construction stage. The concept of “migrant workers” has been widely used in academic circles, as it is in line with the trend of long-term, family-oriented, and sedentary living of the rural population in the context of accelerating the citizenship of the agricultural transfer population in the new urbanization stage. Our empirical study investigates the intrinsic mechanisms of relative deprivation that influence the withdrawal of rural households from their homestead and identifies the mediating effect of social trust and the moderating effect of urban integration.

5. Discussion

Compared with previous studies, this study has more comprehensive considerations. Using the research data of 1320 households in Jinan, we analyzed the interaction and influence of the emotional psychological factors and social environmental factors of the peasants who entered the city on their willingness to withdraw from the homestead. We divided the relative deprivation of farmers into economic deprivation, social deprivation and emotional deprivation innovatively. At the same time, we empirically explored the internal mechanism of the impact of various dimensions of relative deprivation on farmers’ homestead withdrawal and differentiated the intermediary effect of social trust and the regulatory effect of urban integration.

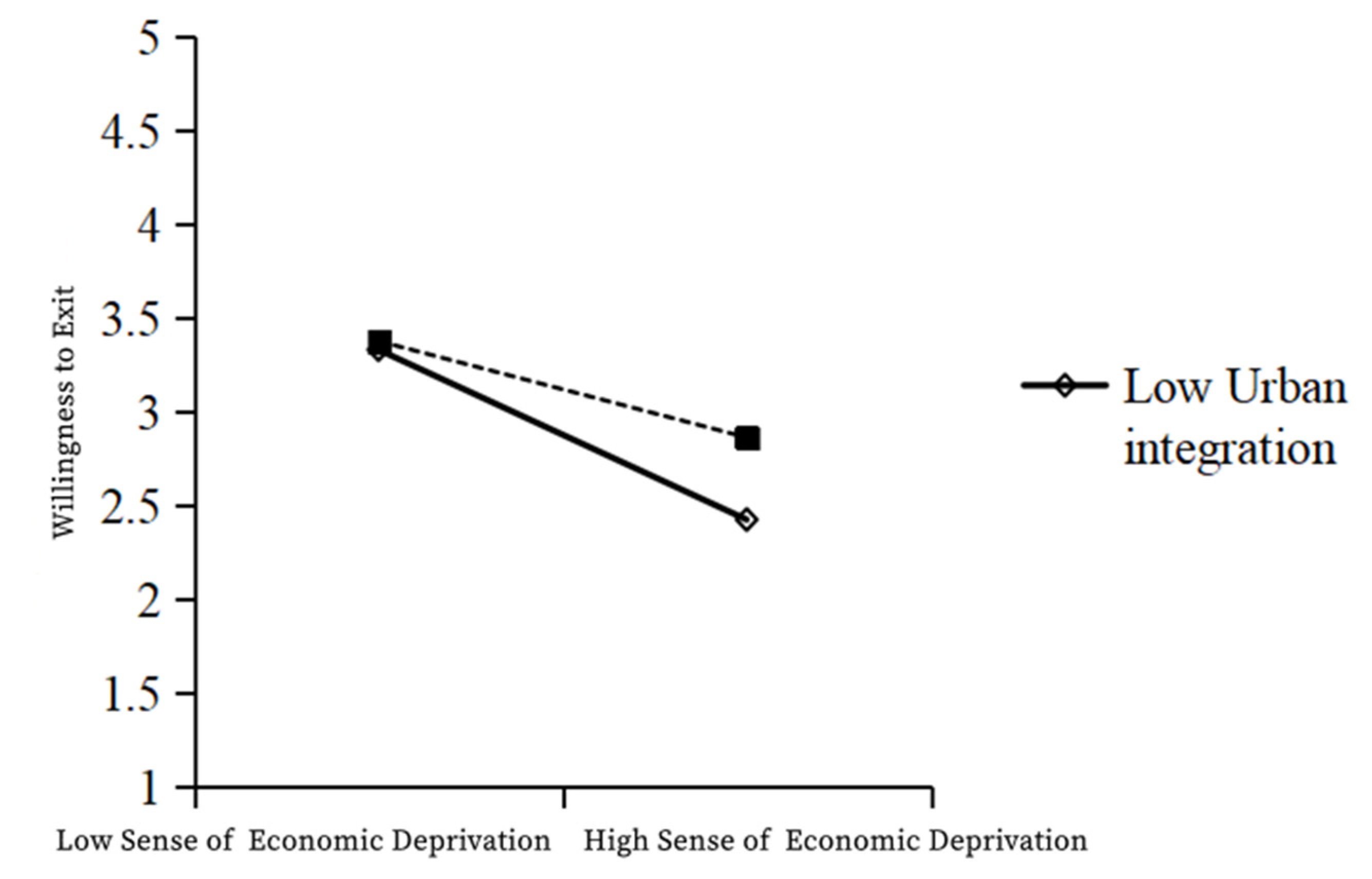

First, we found that relative deprivation has a significant negative effect on the homestead withdrawal behavior of farmers, which inhibits them from withdrawing from their homesteads. Second, social trust was found to play a mediating role in all dimensions of relative deprivation on the homestead withdrawal behavior of farmers. Third, urban integration was found to play a positive moderating role in inhibiting the homestead withdrawal behavior of farmers: the higher the degree of urban integration, the weaker the inhibiting effect of relative deprivation on the withdrawal behavior. Urban integration was also found to play a positive moderating role in inhibiting the effects of social deprivation and emotional deprivation on social trust, such that an increase in the urban integration degree can weaken the influence of emotional deprivation on the homestead withdrawal behavior of farmers.

As a member of the rural collective, the homestead is a source of income. As a necessary place for rural collective members to live and use without compensation for an indefinite period of time, the homestead guarantees the survival needs of members of the collective. Therefore, the homestead also assumes part of the function of social security [

12]. However, when farmers move to the city, it is difficult for them to get a home and to enjoy the same treatment as urban residents, in terms of employment, pension, education, and medical care, such that withdrawal from their homesteads may induce a loss of social security function rights and interests [

8]. Therefore, the implementation of urban farmer homestead withdrawal may generate a strong sense of social deprivation, considering the loss of their social security function and rights. This sense of social deprivation that inhibits their willingness to withdraw from their homestead bases. At the same time, the local society has endowed the homestead with the function of emotional inheritance, carrying the farmer’s love for the land and emotional attachment [

69]. When farmers are faced with the problem of withdrawing from their homestead base, it may bring about an expectation of loss of emotional functional rights and interests, thus generating a strong sense of emotional deprivation, which will inhibit their homestead withdrawal behavior. Although relative deprivation is unavoidable, people can resolve and prevent it in certain ways. Improving farmers’ social trust is one of the effective ways to alleviate the sense of relative deprivation.

Regarding H1, these results supported H1a–H1c. The results are consistent with the results of Pierce, J.L. et al. (2001) [

70], Niu, X. F. et al. (2021) [

71] and Morewedge, C. K. et al. (2009) [

72]. First, the homestead base not only facilitates agricultural production activities and the development of yard economy for farmers but, also, with the state’s emphasis on the usufruct rights of homestead bases, the economic property attributes of the homestead bases are increasingly obvious. Therefore, this will raise the expectation regarding the economic functional value of the homestead, and the expected loss of economic functional rights and interests brought by the withdrawal of the homestead will generate a strong sense of economic deprivation which, in turn, will inhibit the willingness to withdraw from the homestead [

38,

72].

Regarding H2, these results supported H2a–H2c. The results are consistent with the results of Hooghe, M. et al. (2017) [

73] and Fischer, J.A.V. et al. (2013) [

74].Generally speaking, individuals who are successful in socio-economic life are more likely to trust state institutions [

73]. Then, relative to the rural residents who are in a disadvantaged position, the generation of a sense of relative deprivation affects their degree of trust in social, organizational, power, management, and governance systems [

74]. Although a sense of relative deprivation is unavoidable, it can be resolved and prevented in certain ways, providing a means to enhance the social trust of farmers. Social trust is one of the means with which the sense of relative deprivation can be hedged.

Regarding H3, these results supported H3. The results are consistent with the results of Beaudoin, C.E. et al. (2004) [

45], Meng, T. et al. (2014) [

75] and Jiang, J. et al. (2021) [

47]. (1) Good social trust can enhance their courage to withdraw from their homestead bases and eliminate their fear of the unknown risks that may be brought about by the homestead reform [

75]. In turn, this can enhance their willingness to withdraw from their homestead bases [

35]. (2) The higher the trust of farmers in village cadres or councils, the stronger the guarantee mechanism of village cadres or councils and the more confidence they have in the household registration commitment, compensation commitment, and policy commitment being true and credible, which plays an important role in overcoming the psychological “uncertainty in homestead withdrawal” of farmers. Thus, farmers will be motivated to choose to withdraw from their homestead bases. (3) It is believed that judicial, administrative, and legislative bodies will protect the legal rights and interests of the rural-to-urban migrant workers and provide legal support for them to live and work in the city. In this way, the social trust of the urban migrant population can be enhanced, which, in turn, will enhance the willingness of farm households to withdraw from their homesteads.

Regarding H4, these results supported H4a–H4c. The results are consistent with the results of Shen, S. et al. (2022) [

47] and Xu, Z. et al. (2020) [

51]. The specific impact paths of relative deprivation and governmental trust on the willingness of farmers to withdraw can be described as follows: (1) The negative emotional reactions and cognitive changes derived from relative deprivation, as well as the frustration generated by social comparison, lead some members of society with an avoidance mentality to adopt outward attribution. This will, to a certain extent, reduce their trust in the government and promote their recourse to extra-institutional means of benefit protection, which has a negative impact on their willingness to withdraw from their homestead [

76]. (2) The local government is the main government organization related to the distribution of social benefits and the implementation of policies and measures for rural residents [

77]. A sense of relative deprivation will lead to dissatisfaction in the social living standard and social status of rural residents, which will lead them to question the performance of the local government or the competence of its staff [

48]. This will affect the trust of rural residents in the grassroots government, thus affecting the willingness of rural households to withdraw.

Regarding H5, these results supported H5b and H5c, but not supported H5a. Regarding H5a, the results are not consistent with the results of Chen, Z. et al. (2019) [

32]. Theoretically, urban integration can alleviate the economic pressure or reduce the various forms of material deprivation of retiring farmers by providing stable employment, a livable environment and complete public services, thus weakening the negative influence of the sense of economic deprivation on farmers’ homestead withdrawal behavior. However, from the current data, there is no significant impact. It may be because: migrant workers only consider the city as a place to work, and do not consider themselves as part of the city, and they do not obtain the corresponding emotional support and sense of value, which will reduce their willingness to integrate into the local city. This results in an involutional identity of migrant workers, which increases the social distance between migrant workers and the city, thus causing the migrant worker group to voluntarily choose to form their own community network and create a deep separation from the urban society, thus affecting their trust level in the city. [

32]. Regarding H5b and H5c, the results are consistent with the results of Sun, X. et al. (2022) [

31] and Wang, W.W. et al. (2012) [

34]. Firstly, urban integration can expand an individual’s options to participate in political and community activities by giving them various opportunities for social participation, thus enhancing their social rights and abilities through participation in social interactions and, consequently, weakening the negative influence of the sense of social deprivation on the homestead withdrawal behavior of farmers [

31]. Secondly, urban integration involves achieving integration into urban culture and identifying oneself as an “urbanite”. Having a psychologically comfortable urban life can only be achieved when the psychological integration of urban farmers is completed [

34]. Psychological integration will motivate farmers to choose to settle in the city, significantly weakening their cultural and emotional attachment to the homestead, such that they will be more willing to give up their old homes in the countryside and better realize their settlement in the city using the property gains from the withdrawal from their homestead. In other words, psychological integration affects the negative influence on the homestead withdrawal behavior of farmers by weakening their sense of emotional deprivation.

Regarding H6, these results supported H6. The results are consistent with the results of Xu, D. et al. (2020) [

78] and Xu, Y. et al. (2021) [

51]. In general, rural societies are acquaintance-oriented societies, while urban societies are stranger-oriented societies. As urban farmers leave the society of acquaintances and come to the city to make a living, the anonymity and fickleness of human interactions are strong, and it becomes more and more difficult to establish social trust [

79]. The reason for the social distrust of urban migrant farmers is that they are disadvantaged in the distribution of social resources, due to institutional and policy constraints [

78]; that is, therefore, it can be hypothesized that high-quality urban integration can enhance social identity and sense of belonging by improving the quality of life, forming solidarity and stable values, and thus weakening the negative effects of emotional deprivation.

6. Conclusions

In the context of the accelerated development of new urbanization, exploring and establishing a mechanism for the paid withdrawal from rural residential bases is considered a general trend for rural residential base system reform in the future, which is of great significance to revitalize the inefficiently utilized land resources in rural areas, activate the dormant land assets in rural areas, increase the property income of farmers, optimize the land structure and spatial layout of urban and rural areas, and promote rural revitalization. The following aspects should be considered in such processes.

(1) The government should pay attention to and helping farmers to rationalize the property rights of residential bases. On one hand, although the legal level clearly defines that the ownership of residential bases belongs to the collective, most farmers have conducted a de facto “blurring” of the concept of “collective”, such that it is necessary to further clarify and standardize the meaning and scope of “collective. For this reason, publicity and popularization should be carried out by building an information platform regarding residential base policy, in order to gradually weaken the misperception of “possession means ownership” in the traditional thinking of farmers. On the other hand, clarifying property rights relationships and the registration of rights is fundamental. Government should speed up the process of issuing real estate property rights certificates, as well as further deepening the knowledge and understanding of farmers in the process of confirming and issuing certificates.

(2) Weakening the sense of relative deprivation in farmers. First, we need to accelerate the improvement of the market price formation mechanism for rural residential bases. In order to achieve the reasonableness and fairness of the withdrawal compensation and value-added income, the withdrawal cost of farmers should be shared through realization of the property value of residential bases, which will help to weaken their sense of economic deprivation. Second, focus should be placed on the livelihood and development of farmers after their withdrawal from residential bases; improving social acceptance; and achieving fair rights, fair opportunities, and fair distribution in the construction of social security, in order to alleviate the worries of farmers who have withdrawn from their residential bases and weaken their sense of social deprivation. The third is to improve the ability of migrant workers to integrate into society. Governments should focus on designing inclusive development policies to promote the social integration of urban farmers. Link government performance with inclusive governance to improve the government’s incentive for inclusive governance. At the same time, encourage social organizations to synergize with government departments and play a complementary function to ensure the equalization of public services. Attention should also be paid to building a socially inclusive environment with equal opportunities and shared outcomes, eliminating various forms of social exclusion and weakening their sense of emotional deprivation.

(3) Improve and enhance the level of social trust of farming households. Given that social trust has a good external effect, society should actively advocate the concept of equal pay for equal work and equal rights in the same city, guarantee the citizenship of the rural-to-urban migrant workers, and improve the trust level in the rural-to-urban migrant workers. The government, society, and enterprises are the protagonists of social trust building, and these three parties need to coordinate and cooperate in order to effectively promote the social integration of the rural-to-urban migrant workers. The government plays the role of coordination, supervision, and management, with a focus on balancing the social rights of the rural-to-urban migrant workers and granting them equal citizenship rights when designing policies. Society should enhance the city’s inclusive and pluralistic character, adopting an accepting attitude toward the rural-to-urban migrant workers and improving urban governance. Employers should treat foreigners equally, take social responsibility, provide vocational training and benefits to foreigners, and promote professional integration. Only in this way can urban society achieve long-lasting peace and stability, in the process of which the rural-to-urban migrant workers can truly achieve welfare growth and social integration.

First, village and township cadres should effectively perform their duties, reach out to the masses, and respond to needs of farmers and win their trust. Second, construction of residential base withdrawal mechanisms should be conducted differently, according to the local conditions and orderly promotion of residential base withdrawal. Due to the large differences in the locations of homesteads and farm buildings, different family planning patterns, and different levels of social trust, in order to avoid various social risks and contradictions in the process of homestead withdrawal, it is necessary to develop differentiated policies which are applicable to different groups of farmers and avoid one-sided “one-size-fits-all” practices, which may cause adverse social consequences. Third, the social integration capacity of farmers should be improved, through designing inclusive development policies to promote the social integration of farmers into cities. In this context, the performance of the government should be integrated in an inclusive manner to improve the government’s incentive for inclusive governance; second, social organizations should be encouraged to synergize with government departments, playing a complementary function to ensure the equality of public services; and, finally, a socially inclusive environment with equal opportunities and shared results to eliminate various forms of social exclusion should be built up, thus innovating social participation and improving social empowerment.