Quality Food Products as a Tourist Attraction in the Province of Córdoba (Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Protected Geographical Indications and Designation of Origins as Quality Hallmarks of Agri-Food Products

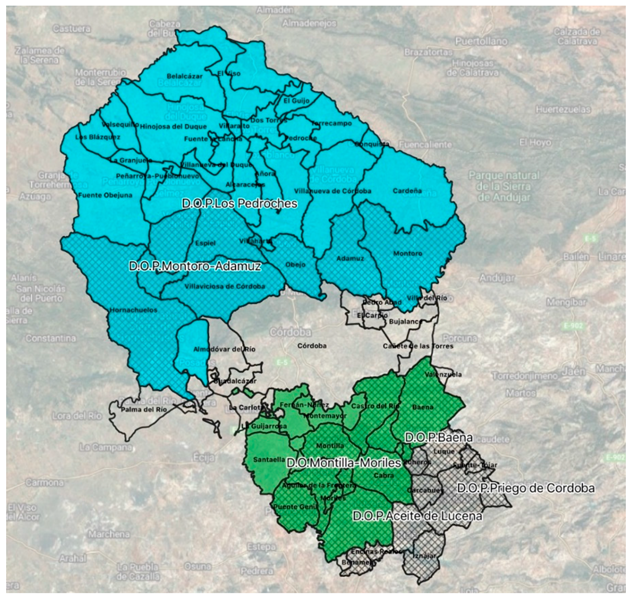

- Iberian Ham: “Los Pedroches” PDO. Located to the north of the province and encompassing 32 municipalities with an area of 3612 km2, the predominant climate in the area is Mediterranean but with a certain continental touch and winds from the Atlantic, with cold winters and long, dry and hot summers and with little rainfall. This climate, together with the structure of the soils, is favorable to the growth of oaks and their fruit (acorn), which is the sustenance of the pigs from which the ham is obtained), forming a dehesas (savannah-like open woodland), a typical ecosystem in the area.

- Wine: Montilla-Moriles Designation of Origin. This environment encompasses a total of 17 municipalities and more than 5000 hectares of vineyards, and distinguishes an area differentiated by the type of soil, considered “Superior” (approximately 1600 hectares). The main grape types are Pedro Ximénez, Layren, Baladí, Verdejo, Moscatel de Grano Menudo, Moscatel de Alejandría, Torrontés, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc and Macabeo.

- Vinegar: Vinagre de Montilla-Moriles Designation of Origin. These vinegars are obtained exclusively by the acetification of PDO wines and have been produced with PDO wines since 2015.

- Oil: The province of Córdoba is the second largest nationwide in terms of olive oil production, with 317,000 tons of oil produced in the 2020–21 season [18]. It has four designations of origin:

- o

- Baena Designation of Origin: This was Spain’s first agri-food Designation of Origin (1971). It encompasses eight municipalities and covers an area of approximately 60,000 hectares, with an average annual production ranging from 30 to 45 million kilos of oil.

- o

- Priego de Córdoba Designation of Origin (1995): This Designation of Origin encompasses the municipalities of Almedinilla, Carcabuey, Fuente Tójar and Priego de Córdoba, covers approximately 30,000 hectares, and is located in the southwest of the province of Córdoba, in Sierra Subbética park.

- o

- Aceite de Lucena Designation of Origin: Located in the south of the province of Córdoba, it encompasses 10 municipalities; it is the newest of the four Designations of Origin (2008) and comprises 73,000 hectares.

- o

- Montoro—Adamuz Designation of Origin (2007): This Designation of Origin encompasses the municipalities of Montoro, Adamuz, Espiel, Hornachuelos, Obejo, Villaharta, Villanueva del Rey and Villaviciosa de Córdoba, as well as the northern part of the municipality of Córdoba. It contains approximately 55,000 hectares of controlled olive groves.

3. Literature Review

- Territory: Gastronomic tourism has been studied in specific regions or countries, such as France, in which Batat [27] investigated the role of Michelin-starred chefs as change-makers and advocates of tourism activities in both rural and urban areas; Italy, in which Privitera et al. [28] analyzed the opportunities of gastronomic tourism for local development around the Sicily region; Greece, in which Pavlidis & Markantonatou [29] analyzed the promotion of gastronomic tourism in the northern regions of Greece; Singapore, in which Chaney & Ryan [26] described the evolution of gastronomic tourism in Singapore; Malaysia, in which Sanip and Mustapha analized the sustainability of gastronomic tourism in Malaysia [30,31]; Mexico, in which Correa [32] determined the factors that can help restaurants to be more competitive in the face of a health crisis in the state of Zacatecas; and Kenya, in which Josphine [33] carried out a critical review of gastronomic tourism development in Kenya.

- Product: Gastronomic tourism has been investigated based on a specific product, such as cheese, in which Medeiros et al. [34] carried out a study on the artisanal cheese of Serro; wine [17]; olive oil, in which Dancausa et al. [3] analyzed olive oil as a gourmet ingredient in contemporary Andalusian cuisine; ham, in which Millán et al. [35] investigated ham tourism as an opportunity for development in rural areas; tea or coffee, in which Seyitoğlu & Alphan [36] examined the tea and coffee museum experience of travelers from around the world; fish, in which Pratiwi’ [37] study aims to develop gastronomic tourism based on fish on the island of Belitung; or prepared dishes [38].

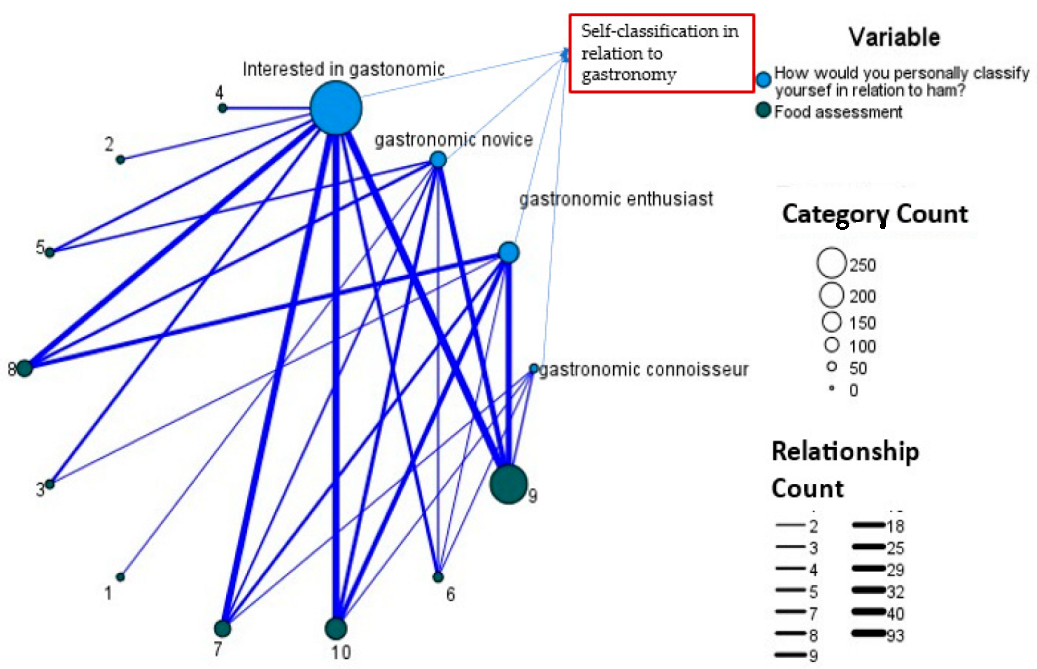

- Motivation: Such studies investigate what motivates tourists to undertake gastronomic tourism [39]. Decrop [40] analyzes the concept of motivation by emphasizing four different components (motives, needs, desires and benefits). Other authors, such as Hernandez & Dancausa [38], distinguish between types of tourist who visit gastronomical destinations, finding that motivation can be a main or secondary factor and classifying gastronomic tourists as follows. Gastronomy connoisseurs (gourmet tourists) are well-versed in gastronomy, and their main motivation for travel is to taste different products or typical dishes of the destinations they visit, as well as to purchase said products and learn in situ. They usually travel continuously throughout the year visiting prestigious restaurants. Gastronomy enthusiasts do not have a high degree of education in gastronomy but know the world of gastronomy relatively well. They typically have a university education, and their main motivation for traveling is to experience firsthand what they have read in different specialized magazines. Individuals interested in gastronomy do not have technical training in gastronomy but are interested in the world of gastronomy. Their main motivation for traveling is to experience typical dishes or products of their destinations, although not exclusively but as a complement to other tourist activities. Gastronomy novices, for various reasons (such as in response to advertising or a desire for new experiences), visit restaurants, wineries, or oil mills despite lacking knowledge regarding gastronomy. Their main motivation for traveling is not related to gastronomy, but they secondarily dedicate a few hours of their journey to gastronomy.

- Satisfaction: These studies analyze how satisfied tourists are with the gastronomy of the destination they visit [45,46,47], investigating how well a destination performs through an analysis of tourist satisfaction, with one of the most important factors when choosing a holiday destination being satisfaction with previous stays [48,49].

4. Materials and Methods

- Simple, viable and accepted by tourists and researchers (viability).

- Reliable and accurate, that is, with error-free measurements.

- Adequate for the problem to be measured.

- A univariate descriptive analysis was conducted to determine the profile of tourists, segmented by product, i.e., wine, oil and ham, with the objective of identifying if there are significant differences between tourists.

- A bivariate analysis was conducted using contingency tables to identify whether there is an association or independence between two variables, using the χ2 statistic (where H0 is that the analyzed variables are independent and H1 is that the analyzed variables are related). The aim of said analysis was to determine the associations between variables, thus allowing the identification of the profiles of gastronomic tourists.

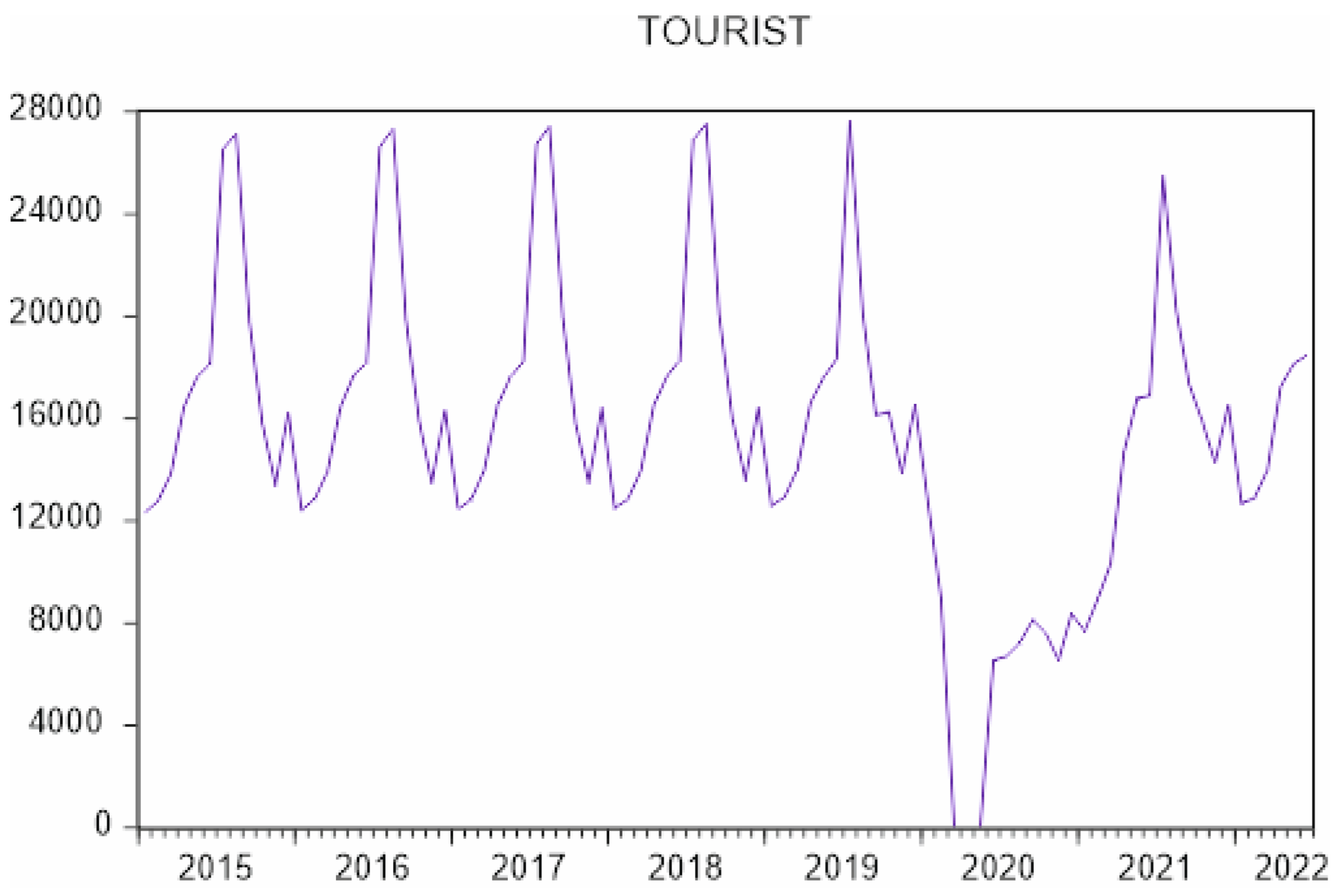

- A SARIMA model (used in previous studies of tourists, such as those by Lim [67] to predict tourist demand in Macao after the COVID-19 pandemic; Yang [56] to predict tourist demand in 29 Chinese regions, and Petrevska [57] to predict tourist demand in Macedonia; Zhang [58] to predict tourist occupancy in a hotel) was used to predict the potential demand of gastronomic tourists in Córdoba, based on a sample (61 observations) collected from February 2015 to May 2022. ARIMA models, popularly known as the Box–Jenkins (BJ) methodology, analyze the probabilistic, or stochastic, properties of economic time series themselves [58]. In this case, this was the number of gastronomic tourists in Córdoba.

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- Create plans and/or complementary activities that will encourage overnight stays in the area. These activities can range from festivities, samplings and fairs to tastings, training courses, competitions and stargazing, taking advantage of the low light at night in many of these rural areas, and lasting more than one day to encourage overnight stays.

- The above would make sense as long as a hospitality and catering infrastructure with the capacity to accommodate these types of events is adequately developed. For this, there must be investments in the area as a complement to the production of goods that is already being carried.

- This symbiosis between products with a designation of origin and geographical area, accompanied by corresponding marketing campaigns, would not take long to bear fruit [85].

- Develop signage within the area that encompasses the three products. Adequate signage, as part of street furniture in these rural areas, would contribute, both as publicity (for those who, at that time, are not engaging in tourist activities) and as information for tourists who wish to move from one place to another. Not surprisingly, through our research, lack of signage was identified as an item that need to be improved for designations of origin in the province of Córdoba.

- The seven designations of origin should combine their efforts not only to develop economies of scale that minimize the associated costs of advertising and promotion, but also, as all products are highly recommended both from the gastronomic and nutritional perspectives, to organize routes that cover one, two or all three products. For example, dinners or lunches could be organized between olive producers or vineyards, focusing on products of the land, after a day in which the tourists have visited an oil mill, a ham curing facility and/or a winery. Such events could be accompanied by live performances, if desired.

- Generate awareness of “sharing tourism” among the different designations of origin. That is, to offer a wider variety of activities and products so that potential tourists do not need to leave the area.

- Create an association among the seven PDOs in the province of Córdoba that would support their interests, with campaigns aimed at attracting investments and promoting tourism. The similarity of offerings and the areas in which they are developed make this type of union very viable because conflicting interests are highly unusual.

- All of the above would be much easier with the involvement and cooperation of economic agents and public administration. The management and processing of grants and subsidies, national and international promotion, public events, and the designation of protected areas or natural parks, etc., will be more effective if the highest possible levels of decision-making capacity participate.

- The implementation of these “recommendations” should be made with the supervision of a panel of experts related to different areas of knowledge, for example, economists, lawyers, agronomists, forestry engineers, architects, biologists, landscapers, etc., to minimize the risks that can lead to overcrowding natural landscapes of incalculable beauty as much as possible.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfiero, S.; Bonadonna, A.; Cane, M.; Lo Giudice, A. Street food: A tool for promoting tradition, territory, and tourism. Tour. Anal. 2019, 24, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohard, J.C.R.; Martínez, J.D.S.; Simón, V.J.G. Valorizando el territorio con alimentos excelentes: Los aceites de alta gama en el sur de España. In Arethuse: Scientific Journal of Economics and Business Management; Società Editrice Esculapio: Bologna, Italy, 2013; pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Dancausa, M.G.; Millán, M.G.; Huete, N. Olive oil as a gourmet ingredient in contemporary cuisine. A gastronomic tourism proposal. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 29, 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armesto, X.A.; Gómez, B. Productos agroalimentarios de calidad, turismo y desarrollo local: El caso del Priorat. Cuad. Geográficos 2004, 34, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Csurgó, B.; Hindley, C.; Smith, M.K. The role of gastronomic tourism in rural development. In The Routledge Handbook of Gastronomic Tourism; Saurabh Kumar Dixit, Ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Willett, W.C. The Mediterranean diet and health: A comprehensive overview. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 290, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Estruch, R.; Corella, D.; Fitó, M.; Ros, E.; Predimed Investigators. Benefits of the Mediterranean diet: Insights from the PREDIMED study. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 58, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavicchi, A.; Santini, C. Food tourism and foodies in Italy: The role of the Mediterranean diet between resilience and sustainability. In Sustainable Tourism Practices in the Mediterranean; Tüzün, I., Ergül, M., Johnson, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Velissariou, E.; Vasilaki, E. Local gastronomy and tourist behavior: Research on domestic tourism in Greece. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 9, 120–143. [Google Scholar]

- Sáez-Almendros, S.; Obrador, B.; Bach-Faig, A.; Serra-Majem, L. Environmental footprints of Mediterranean versus Western dietary patterns: Beyond the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet. Environ. Health 2013, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussaillant, C.; Echeverría, G.; Urquiaga, I.; Velasco, N.; Rigotti, A. Evidencia actual sobre los beneficios de la dieta mediterránea en salud. Rev. Méd. Chile 2016, 144, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, A.; Roman, B.; Serra, L. El porqué de los beneficios de la dieta mediterránea. Jano Med. Humanid. 2007, 1648, 26. [Google Scholar]

- De Uña-Álvarez, E.; Villarino-Pérez, M. Linking wine culture, identity, tourism and rural development in a denomination of origin territory (NW of Spain). Cuad. Tur. 2019, 44, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pouplana, J.R. Las tendencias del turismo pos-COVID-19. Tecnohotel Rev. Prof. Hostel. Restauración 2020, 485, 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Márquez, A.M.; Hernández Ortiz, M.J. Cooperación y sociedades cooperativas: El caso de la Denominación de Origen Sierra Mágina. Rev. Estud. Coop. Revesco 2001, 74, 123–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación. Datos de las Denominaciones de Origen Protegidas (D.O.P.), Indicaciones Geográficas Protegidas (I.G.P.) y Especialidades Tradicionales Garantizadas (E.T.G.) de Productos Agroalimentarios; MAPA: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cava, J.A.; Millán, M.G.; Dancausa, M.G. Enotourism in Southern Spain: The Montilla-Moriles PDO. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consejeria de Agricultura. Ganadería, Pesca y Desarrollo Sostenible Junta de Andalucía. 2022. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/agriculturaypesca/observatorio/servlet/FrontController?action=RecordContent&table=11114&element=3868182&subsector=&2022 (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- López-Guzmán, T.; Sánchez-Cañizares, S. Gastronomy, tourism and destination differentiation: A case study in Spain. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2012, 1, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Beltrán, J.; López-Guzmán, T.; Santa-Cruz, F.G. Gastronomy and tourism: Profile and motivation of international tourism in the city of Córdoba, Spain. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2016, 14, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gálvez, J.C.; Medina-Viruel, M.J.; Jara-Alba, C.; López-Guzmán, T. Segmentation of food market visitors in World Heritage Sites. Case study of the city of Córdoba (Spain). Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1139–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, V.; Freire, D.A.; Guananga, N.I.; Garlobo, E.R.; Alarcón, M.R.; Aguilera, P. Gastronomía ecuatoriana y turismo local. Dilemas Contemp. Educ. Política Valores 2018, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, V. A review of Indian tourism industry with SWOT analysis. J. Tour. Hosp. 2016, 5, 196–200. [Google Scholar]

- Turgarini, D.; Pridia, H.; Soemantri, L.L. Gastronomic Tourism Travel Routes Based on Android Applications in Ternate City. J. Gastron. Tour. 2021, 8, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.F.; Martinez, L.F.; Mindiola, L.A. Diseño de una ruta gastronómica de los emprendimientos de comidas típicas en la ciudad de Santo Domingo. Dilemas Contemp. Educ. Política Valores 2020, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, S.; Ryan, C. Analyzing the evolution of Singapore’s World Gourmet Summit: An example of gastronomic tourism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batat, W. The role of luxury gastronomy in culinary tourism: An ethnographic study of Michelin-Starred restaurants in France. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, D.; Nedelcu, A.; Nicula, V. Gastronomic and food tourism as an economic local resource: Case studies from Romania and Italy. GeoJournal Tour. Geosites 2018, 21, 143–157. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis, G.; Markantonatou, S. Gastronomic tourism in Greece and beyond: A thorough review. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 21, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanip, M.N.A.M.; Mustapha, R. Sustainability of Gastronomic Tourism in Malaysia: Theoretical Context. Int. J. Asian Soc. Sci. 2020, 10, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, H. Gastronomy, tourism, and the soft power of Malaysia. Sage Open 2018, 8, 2158244018809211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, L.Á. Gastronomic tourism, factors that affect the competitiveness of restaurants in Zacatecas, México. Tur. Patrim. 2022, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josphine, J. A critical review of gastronomic tourism development in Kenya. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 4, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, M.D.L.; da Cunha, J.A.C.; Passador, J.L. Gastronomic tourism and regional development: A study based on the minas artisanal cheese of Serro. Cad. Virtual Tur. 2018, 18, 168–189. [Google Scholar]

- Millán, M.G.; Sánchez-Ollero, J.L.; Dancausa, M.G. Ham Tourism in Andalusia: An Untapped Opportunity in the Rural Environment. Foods 2022, 11, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyitoğlu, F.; Alphan, E. Gastronomy tourism through tea and coffee: Travellers’ museum experience. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 15, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, Y. Traditional Fish Gangan: An Icon of Gastronomic Tourism from Belitung Island. Gastron. Tour. J. 2020, 7, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.; Dancausa, M.G. Culinary Tourism. Traditional Gastronomy of Córdoba (Spain). Estud. Perspect. En Tur. 2018, 27, 413–430. [Google Scholar]

- Berbel-Pineda, J.M.; Palacios-Florencio, B.; Ramírez-Hurtado, J.M.; Santos-Roldán, L. Gastronomic experience as a factor of motivation in the tourist movements. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2019, 18, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decrop, A. Tourists’ Decision-Making and Behaviour Processes. In Consumer Behaviour in Travel and Tourism; Pizam, A., Mansfeld, Y., Eds.; The Haworth Hospitality Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; pp. 103–133. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti, S.; Medina-Viruel, M.G.; Di-Clemente, E.; Fruet-Cardozo, J.V. Motivations of the Culinary Tourist in the City of Trapani, Italy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, F.; Moral-Cuadra, S.; López-Guzman, T. Gastronomic Motivations and Perceived Value of Foreign Tourists in the City of Oruro (Bolivia): An Analysis Based on Structural Equations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-Cuadra, S.; Acero, R.; Rueda, R.; Salinas, E. Relationship between consumer motivation and the gastronomic experience of olive oil tourism in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova-Buiza, F.; Gabriel-Campos, E.; Castaño-Prieto, L.; Garcia-Garcia, L. The Gastronomic Experience: Motivation and Satisfaction of the Gastronomic Tourist—The Case of Puno City (Peru). Sustainability 2021, 13, 9170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.; Garau, J. Tourist satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.; Pritchard, M.P.; Smith, B. The destination product and its impact on traveller perceptions. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M. Destination benchmarking. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.; Cladera, M. Repeat visitation in mature sun and sand holiday destinations. J. Travel Res. 2006, 44, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Min, H.K. Enjoyment or indulgence: What draws the line in hedonic food consumption? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 104, 103228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fettahlıoğlu, H.S.; Yıldız, A.; Birin, C. Hedonik Tüketim Davranışları: Kahramanmaraş Sütçü İmam Üniversitesi ve Adıyaman Üniversitesi Öğrencilerinin Hedonik Alışveriş Davranışlarında Demografik Faktörlerin Etkisinin Karşılaştırmalı Olarak Analizi. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 27, 307–331. [Google Scholar]

- Huertas, T.E.; Suarez, E.S.; Cuetara, L.M. Perfil del cliente gastronómico del cantón Mocha. Rev. UNIANDES Epistem. 2016, 3, 497–506. [Google Scholar]

- Dancausa, M.G.; Millán, M.G.; Hernández, R. Analysis of the demand for gastronomic tourism in Andalusia (Spain). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-Cuadra, S.; Solano-Sánchez, M.Á.; Menor-Campos, A.; López-Guzmán, T. Discovering gastronomic tourists’ profiles through artificial neural networks: Analysis, opinions and attitudes. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2022, 47, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menor-Campos, A.; Hidalgo-Fernández, A.; López-Felipe, T.; Jara-Alba, C. Gastronomía local, cultura y turismo en Ciudades Patrimonio de la Humanidad: El comportamiento del turista extranjero. Investig. Turísticas 2022, 23, 140–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, H. Spatial-temporal forecasting of tourism demand. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrevska, B. Predicting tourism demand by ARIMA models. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2017, 30, 939–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Pan, B.; Zhang, G. Weekly hotel occupancy forecasting of a tourism destination. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Priego, M.A.; Garcia-Moreno Garcia, M.B.; Gomez-Casero, G.; Caridad, L. Segmentation based on the gastronomic motivations of tourists: The case of the Costa Del Sol (Spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Yébenes, M.J.; Rodríguez, F.; Carmona, L. Validación de cuestionarios. Reumatol. Clínica 2009, 5, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villavicencio-Caparó, E.; Ruiz-García, V.; Cabrera-Duffaut, A. Validation of questionnaires. Rev. OACTIVA UC Cuenca 2016, 1, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Cañizares, S.M.S. La gastronomía como motivación para viajar. Un estudio sobre el turismo culinario en Córdoba. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2012, 10, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán-Vázquez, G.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.; Amador-Hidalgo, L. Olive oil tourism: Promoting rural development in Andalusia (Spain). Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 21, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.E.; Steindorf, K. Statistical methods for the validation of questionnaires. Methods of information in medicine 2006, 45, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, A.M.; Khalid, W. Questionnaire designing and validation. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2012, 62, 514. [Google Scholar]

- Cava, J.A.; Millán, G.; Hernandez, R. Analysis of the Tourism Demand for Iberian Ham Routes in Andalusia (Southern Spain): Tourist Profile. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; To, W.M. The economic impact of a global pandemic on the tourism economy: The case of COVID-19 and Macao’s destination-and gambling-dependent economy. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, D. Essentials of Ecomnometrics, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: San Mateo, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–632. [Google Scholar]

- Millán, G.; Pérez, L.M. Comparación del perfil de enoturistas y oleoturistas en España. Un estudio de caso. Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2014, 11, 167–188. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, A.D.; Northcote, J. The development of olive tourism in Western Australia: A case study of an emerging tourism industry. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S. La gastronomía como atractivo turístico primario de un destino: El Turismo Gastronómico en Mealhada—Portugal. Estud. Y Perspect. En Tur. 2011, 20, 738–752. [Google Scholar]

- Orgaz, F.; López, T. Análisis del perfil, motivaciones, y valoraciones de los turistas gastronómicos. El caso de la República Dominicana. Ara: Rev. Investig. Tur. 2017, 5, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, J.M.; Salinas, J.A.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Ostos, M.D.S. Analysis of tourism seasonality as a factor limiting the sustainable development of rural areas. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 45–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgado, J.A.; Hernández, J.M.; Duarte, P.A.O. El perfil del turista de eventos culturales: Un análisis exploratorio. Cult. Desarro. Nuevas Tecnol. VII Jorn. Investig. Tur. 2014, 1, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mejía, M.O.; Franco, W.C.; Franco, M.C.; Flores, F.Z. Perfil y Preferencias de los Visitantes en Destinos Con Potencial Gastronómico: Caso ‘Las Huecas’ de Guayaquil [Ecuador]. Rosa Ventos 2017, 9, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, J.S.; Roig, B.; Valencia, S.; Rabadan, M.T.; Martinez, C. Actitud hacia la gastronomía local de los turistas: Dimensiones y segmentación de mercado. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2008, 6, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, S.; Remondes, J.; Costa, A.P. Estudo do perfil e motivações do enoturista: O caso da quinta da Gaivosa. Cult. Rev. De Cult. Tur. 2021, 15, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán-Vázquez, G.; Pablo-Romero, M.; Sánchez Rivas, J. Oleotourism as a Sustainable Product: An Analysis of Its Demand in the South of Spain (Andalusia). Sustainability 2018, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorrano, P.; Fait, M.; Maizza, A.; Vrontis, D. Online branding strategy for wine tourism competitiveness. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2019, 31, 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, S. Turismo gastronómico, un factor de diferenciación. Millenium 2018, 2, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=1995 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía. 2022. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/badea/informe/datosaldia?CodOper=b3_271&idNode=9801#51246 (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Marzo-Navarro, M.; Pedraja-Iglesias, M. Use of a winery’s website for wine tourism development: Rioja region. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2021, 33, 523–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Moital, M.; Oliveira, N.; da Costa, C.F. Multidimensional segmentation of gastronomic tourists based on motivation and satisfaction. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2009, 2, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, A.; Varley, P. Food tourism policy: Deconstructing boundaries of taste and. Tour. Manag. 2016, 60, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Agri-Food Products | PDO | PGI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | Andalusia | Córdoba | Spain | Andalusia | Córdoba | |

| Fresh meat (and offal) | - | - | - | 22 | 1 | - |

| Meat products | 5 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 2 | - |

| Cheese | 27 | - | - | 2 | - | - |

| Other animal products (honey) | 3 | 1 | - | 4 | - | - |

| Oils and fats (31 oils and 2 butters) | 30 | 12 | 4 | 3 | - | - |

| Fruits, vegetables and fresh and transformed cereals | 26 | 3 | - | 36 | 3 | - |

| Fish, seafood and fresh crustaceans and derived products | 1 | - | - | 4 | 4 | - |

| Other products (saffron, paprika, tiger nut, hazelnut, vinegar and cider) | 9 | 3 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Bakery, confectionary, pastry and dessert products | - | - | - | 16 | 4 | - |

| Cochineal | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total PDO and PGI of agri-food products | 102 | 21 | 6 | 98 | 14 | 0 |

| Wines with designation of origin (DO) | 74 | 7 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Wines with qualified design of origin (DO Ca) | 2 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Quality wines with geographical indication (QW) | 10 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Paid wines (PV) | 11 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Wines with geographical indication (GI) | - | - | - | 41 | 16 | 2 |

| Aromatized wines | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Total PDO and PGI of Wines | 97 | 8 | 1 | 42 | 17 | 2 |

| Spirits with PGI | - | - | - | 19 | 1 | - |

| Total PDO and PGI | 199 | 30 | 7 | 159 | 32 | 0 |

| Demand Survey | |

|---|---|

| Population | Tourists of both sexes over 18 years old who visited a gastronomic route or PDO in Córdoba |

| Sample size | 315 |

| Sampling error | ±4.2% |

| Confidence level | 95%; p = q = 0.5 |

| Sampling system | Simple random |

| Date of fieldwork | September 2021–January 2022 |

| Block | Question | Classification | Percentage of Ham Tourists | Percentage of Enotourists | Percentage of Oil Tourists |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal characteristics of gastronomic tourists | Age | 18–29 years | 14.2 | 23.0 | 14.4 |

| 30–39 years | 27.1 | 28.4 | 27.3 | ||

| 40–49 years | 20.3 | 32.0 | 19.3 | ||

| 50–59 years | 31.1 | 13.2 | 30.4 | ||

| Over 60 years | 7.3 | 3.4 | 8.6 | ||

| Education level | No completed studies | 9.3 | 1.0 | 9.4 | |

| Primary and secondary studies | 19.6 | 32.9 | 18.6 | ||

| Secondary Bachelor | 43.8 | 40.1 | 38.5 | ||

| Higher studies | 27.4 | 26.0 | 33.5 | ||

| Gender | Male | 57.5 | 51.2 | 58.2 | |

| Female | 42.5 | 49.8 | 41.8 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 26.9 | 35.0 | 26.9 | |

| Married | 47.7 | 44.0 | 48.2 | ||

| Divorced/separated | 25.2 | 20.3 | 24.3 | ||

| Other | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 | ||

| Monthly income level of the family unit | Less than EUR 1000 | 19.8 | 23.9 | 19.8 | |

| EUR 1001–1500 | 19.8 | 47.6 | 20.0 | ||

| EUR 1501–2000 | 30.3 | 18.3 | 30.0 | ||

| EUR 2001–2500 | 20.0 | 7.4 | 20.0 | ||

| More than EUR 2500 | 10 | 2.8 | 10.2 | ||

| Who do you travel with? | Alone | 3.2 | 4.7 | 2.0 | |

| Accompanied by my partner | 48.9 | 45.6 | 49.4 | ||

| With friends | 37.7 | 32.3 | 38.4 | ||

| With relatives | 10.3 | 17.4 | 10.2 | ||

| Where are you from? | Andalusia | 58.9 | 43.1 | 59.4 | |

| Rest of Spain (except Andalusia) | 30.1 | 34.3 | 29.8 | ||

| European Union (except Spain) | 10.0 | 12.5 | 10.2 | ||

| United States | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | ||

| Rest of the world (except European Union) | 0.7 | 10 | 0.5 | ||

| Employment situation | Employed by others | 61.4 | 70.1 | 62.2 | |

| Self-employed | 10.2 | 8.5 | 10.2 | ||

| Retired | 17.4 | 7.4 | 17.3 | ||

| Unemployed | 8.3 | 3.4 | 8.1 | ||

| Student | 2.7 | 10.6 | 2.2 | ||

| Duration of the trip | Less than 24 h | 53.7 | 83.2 | 54.2 | |

| 1–3 days | 34.3 | 9.7 | 33.3 | ||

| More than 3 days | 12.0 | 7.1 | 12.5 | ||

| Daily expenditure | Less than EUR 30 | 11.2 | 11.9 | 11.1 | |

| EUR 30–65EUR 66–100 | 24.0 | 17.6 | 23.9 | ||

| 42.1 | 22.4 | 43.9 | |||

| More than EUR 100 | 22.7 | 48.1 | 21.1 |

| Block | Question | Classification | Percentage of Ham Tourists | Percentage of Enotourists | Percentage of Oil Tourists |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questions about the visit | Number of people who travelled the route with you | 1 person | 8.3 | 15.6 | 12.2 |

| 2 to 4 people | 76.2 | 70.1 | 66.3 | ||

| More than 4 people | 15.5 | 14.3 | 21.6 | ||

| Has the PDO or the gastronomic route met your expectations? | Yes | 84.2 | 79.2 | 80.6 | |

| No | 15.8 | 20.8 | 19.4 | ||

| What would you improve? | Nothing | 0.3 | 1.3 | 0.9 | |

| Signage | 50.6 | 38.5 | 47.7 | ||

| Explanation of the route or the PDO | 24.8 | 40.1 | 39.1 | ||

| More audiovisual media | 18.3 | 15.9 | 11.7 | ||

| Other | 6 | 4.2 | 0.6 | ||

| Would you be interested in receiving more information after the visit? | Yes, if it is free | 62.3 | 74.3 | 59.7 | |

| Yes, in any case | 17.5 | 6.2 | 20.2 | ||

| I do not think it’s necessary | 20.2 | 19.5 | 10.2 | ||

| Did you come expressly for this gastronomic route, or was it offered to you in Andalusia? | I came expressly from my place of origin | 76.1 | 59.7 | 49.4 | |

| It was circumstantial; they offered it to me | 23.9 | 40.3 | 51.6 | ||

| Does the price paid seem to be consistent with the route? | Yes | 92.7 | 90.1 | 96.3 | |

| No | 3.8 | 9.9 | 3.8 | ||

| How did you learn about the route? | Travel agencies | 5.2 | 14.6 | 13.9 | |

| Online, through social networks | 61.4 | 35.8 | 48.1 | ||

| On the recommendation of friends and family | 31.3 | 45.8 | 32.2 | ||

| Other media | 2.1 | 3.9 | 5.8 | ||

| I would repeat the experience using a similar route | Yes | 82.3 | 87.1 | 96.6 | |

| No | 17.7 | 12.8 | 3.4 | ||

| Degree of satisfaction with the visit | Less than 25% | 6.0 | 4.4 | 0.6 | |

| 25–50% | 4.2 | 7.9 | 1.1 | ||

| 51–75% | 8.3 | 5.4 | 2.7 | ||

| 76–99% | 61.4 | 64.2 | 57.0 | ||

| 100% | 20.1 | 18.1 | 38.6 |

| Block | Question | Classification | Percentage of Ham Tourists | Percentage of Enotourists | Percentage of Oil Tourists |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questions about the motivation for the visit | What were the reasons for the visit? | Learn the culinary tradition of the destination | 40.2 | 31 | 39.6 |

| Learn the process of making oil/wine/ham and visit oil mills, ham curing facilities, wineries | 50.5 | 65.8 | 50.3 | ||

| Attend gastronomic festivals | 9.3 | 3.2 | 10.1 | ||

| How do you rate the current situation in terms of tourism management at sites like the ones you have visited? | Good | 49.3 | 39.4 | 51.6 | |

| Fine | 29.1 | 52.8 | 27.9 | ||

| Bad | 21.6 | 7.8 | 20.5 | ||

| What would you think about the creation of a combined route of various gastronomic products with theatrical performances? | I agree | 98.1 | 99.3 | 96.5 | |

| I do not agree; I prefer to visit a single gastronomic route and not several | 1.9 | 0.7 | 3.5 |

| Associated Variables | χ2 | df | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age/Motivation for engaging in gastronomic tourism | 325.71 | 8 | <0.001 |

| Satisfaction with visit/gender | 11.86 | 4 | 0.019 |

| Satisfaction/self-classification regarding gastronomy | 62.32 | 16 | <0.001 |

| Satisfaction/Place of origin | 241.47 | 16 | <0.001 |

| Satisfaction/Education level | 264.89 | 12 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR (1) | −0.497661 | 0.101278 | −4.913816 | 0.0000 |

| SMA (12) | −0.942206 | 0.062879 | −14.98443 | 0.0000 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | z-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance Equation | ||||

| C | 1.14 × 10−4 | 2.47 × 10−5 | 4.620412 | 0.0000 |

| RESID (−1)^2 | 13.83276 | 0.962786 | 14.36743 | 0.0000 |

| GARCH (−1) | 0.114353 | 0.012500 | 9.147971 | 0.0000 |

| Year/Month | Tourists | Year/Month | Tourists | Difference | % Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022/07 | 28,110 | 2019/07 | 27,590 | 520 | 1.88 |

| 2022/08 | 22,345 | 2019/08 | 20,140 | 2205 | 10.94 |

| 2022/09 | 17,524 | 2019/09 | 16,130 | 1394 | 8.64 |

| 2022/10 | 18,132 | 2019/10 | 16,240 | 1892 | 11.65 |

| 2022/11 | 15,625 | 2019/11 | 13,830 | 1795 | 12.97 |

| 2022/12 | 22,736 | 2019/12 | 16,560 | 6176 | 37.29 |

| total | 124,472 | 110,490 | 13,982 | 12.65 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dancausa Millán, M.G.; Millán Vázquez de la Torre, M.G. Quality Food Products as a Tourist Attraction in the Province of Córdoba (Spain). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912754

Dancausa Millán MG, Millán Vázquez de la Torre MG. Quality Food Products as a Tourist Attraction in the Province of Córdoba (Spain). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912754

Chicago/Turabian StyleDancausa Millán, Mª Genoveva, and Mª Genoveva Millán Vázquez de la Torre. 2022. "Quality Food Products as a Tourist Attraction in the Province of Córdoba (Spain)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912754

APA StyleDancausa Millán, M. G., & Millán Vázquez de la Torre, M. G. (2022). Quality Food Products as a Tourist Attraction in the Province of Córdoba (Spain). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912754