The Relationships among Proactive Personality, Work Engagement, and Perceived Work Competence in Sports Coaches: The Moderating Role of Perceived Supervisor Support

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Job Demands-Resources Model

1.2. Proactive Personality and Perceived Work Competence

1.3. The Mediating Role of Work Engagement

1.4. The Moderating Role of Perceived Supervisor Support

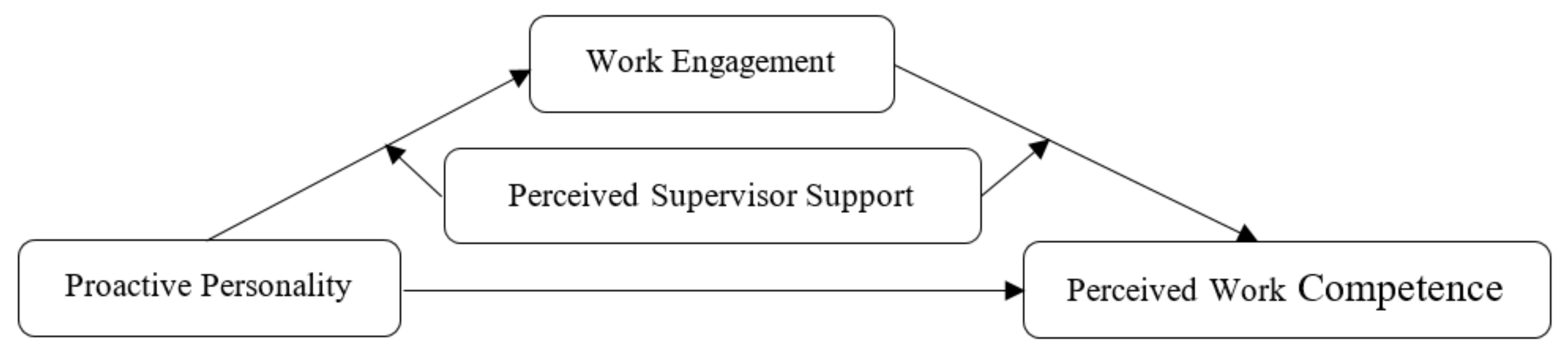

1.5. The Moderated Mediating Effect of Supervisor Support

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Proactive Personality

2.2.2. Work Engagement

2.2.3. Perceived Work Competence

2.2.4. Perceived Supervisor Support

2.2.5. Control Variables

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

3.2. Proactive Personality and Perceived Work Competence

3.3. The Mediating Role of Work Engagement

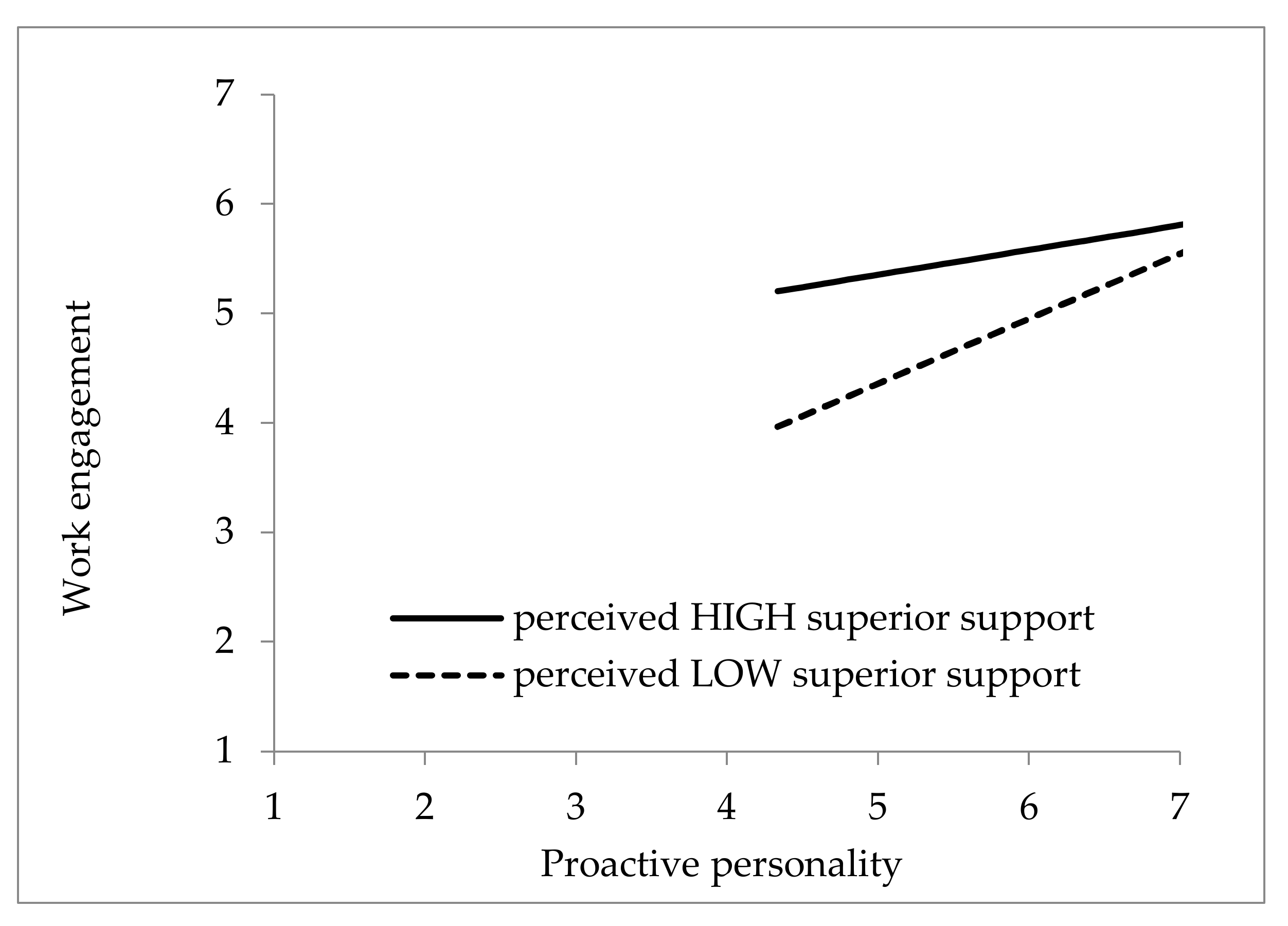

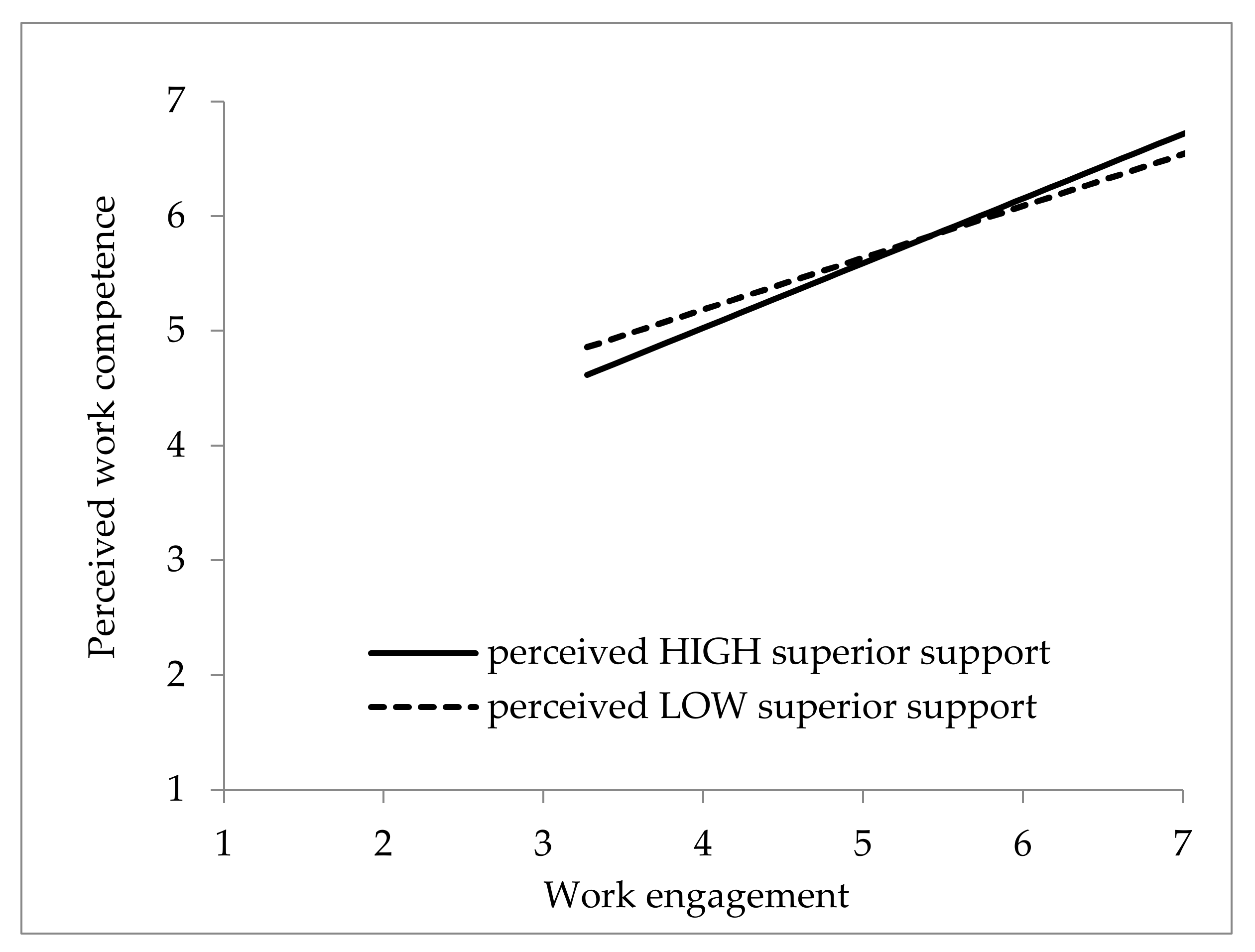

3.4. The Moderating Role of Supervisor Support

3.5. Moderated Mediation Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Petitpas, A.J.; Cornelius, A.E.; Van Raalte, J.L.; Jones, T. A framework for planning youth sport programs that foster psychosocial development. Sport Psychol. 2005, 19, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otter, R.T.; Bakker, A.C.; van der Zwaard, S.; Toering, T.; Goudsmit, J.F.; Stoter, I.K.; de Jong, J. Perceived training of junior speed skaters versus the coach’s intention: Does a mismatch relate to perceived stress and recovery? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagiwara, G.; Kurita, K.; Warisawa, S.; Hachisuka, S.; Ueda, J.; Ehara, K.; Ishikawa, K.; Inoue, K.; Akiyama, D.; Nakada, M.; et al. Competencies that japanese collegiate sports coaches require for dual-career support for student athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertram, R.; Culver, D.M.; Gilbert, W. A university sport coach community of practice: Using a value creation framework to explore learning and social interactions. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2017, 12, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, M.E. The concept of competence: Themes and variations. In Competence Development; Marlowe, H., Weinberg, R., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 3–49. [Google Scholar]

- Berdicchia, D.; Masino, G. Leading by leaving: Exploring the relationship between supervisory control, job crafting, self-competence and performance. J. Manag. Organ. 2019, 25, 572–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Raja, U.; Anjum, M.; Bouckenooghe, D. Perceived competence and impression management: Testing the mediating and moderating mechanisms. Int. J. Psychol. 2019, 54, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurst, R.; Prescott, J. Counselling as a calling: Meaning in life and perceived self-competence in counselling students. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2022, 22, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Putnick, D.L.; Hendricks, C.; Bornstein, M.H. Long-term effects of parenting and adolescent self-competence for the development of optimism and neuroticism. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 1544–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, C.; Spencer, C. A circular and dynamic model of the process of job design. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2007, 80, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Collins, C.G. Taking stock: Integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behaviors. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Kraimer, M.L.; Crant, J.M. What do proactive people do? A longitudinal model linking proactive personality and career success. Pers. Psychol. 2001, 54, 845–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, B., Jr.; Marler, L.E. Change driven by nature: A meta-analytic review of the proactive personality literature. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 75, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.; Kapstad, J.C. Perceived competence mobilization: An explorative study of predictors and impact on turnover intentions. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 20, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madjar, N.; Oldham, G.R.; Pratt, M.G. There’s no place like home? The contributions of work and nonwork creativity support to employees’ creative performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 757–767. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Bernstein, J.H.; Brown, K.W. Weekends, work, and well-being: Psychological need satisfactions and day of the week effects on mood, vitality, and physical symptoms. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 29, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 2, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraimer, M.L.; Seibert, S.E.; Wayne, S.J.; Liden, R.C.; Bravo, J. Antecedents and outcomes of organizational support for development: The critical role of career opportunities. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.C.; Lin, S.H.; Cheng, C.F.; Wu, M.H. When coaching is a calling: A moderated mediating model among school sports coaches. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2022, 17, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, T.S.; Crant, J.M. The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. J. Organ. Behav. 1993, 14, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Social cognitive career theory at 25: Empirical status of the interest, choice, and performance models. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 115, 103316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Guan, Y.; Wu, J.; Han, L.; Zhu, F.; Fu, X.; Yu, J. The interplay of proactive personality and internship quality in Chinese university graduates’ job search success: The role of career adaptability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 109, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. Person-job fit: A conceptual integration, literature review, and methodological critique. In International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Cooper, C., Robertson, I., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 283–357. [Google Scholar]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D.; Wanberg, C.R. Unwrapping the organizational entry process: Disentangling multiple antecedents and their pathways to adjustment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 779–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crant, J.M. Proactive behavior in organizations. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gist, M.E. Self-efficacy: Implications for organizational behavior and human resource management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M.T. The assessment of professional competence. Eval. Health Prof. 1992, 15, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterwall, B. Linking proactive personality and proactive behavior: The mediating effect of regulatory focus. J. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 19, 108–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Tims, M.; Derks, D. Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Cai, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ma, J. Linking empowering leadership and employee work engagement: The effects of person-job fit, person-group fit, and proactive personality. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynie, J.J.; Flynn, C.B.; Mauldin, S. Proactive personality, core self-evaluations, and engagement: The role of negative emotions. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Gao, J.; You, X. Proactive personality and job satisfaction: The mediating effects of self-efficacy and work engagement in teachers. Curr. Psychol. 2017, 36, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z. Proactive personality and career adaptability: The role of thriving at work. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 98, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolentino, L.; Garcia, P.R.J.M.; Lu, V.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Bordia, P.; Plewa, C. Career adaptation: The relation of adaptability to goal orientation, proactive personality, and career optimism. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 84, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, C.L.; Dougherty, T.W. A review and an integration of research on job burnout. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 621–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.T.; Ashforth, B.E. A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottke, J.L.; Sharafinski, C.E. Measuring perceived supervisory and organizational support. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1988, 48, 1075–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. When the presence of creative coworkers is related to creativity: Role of supervisor close monitoring, developmental feedback, and creative personality. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniëls, M.C. Proactivity and supervisor support in creative process engagement. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtessis, J.N.; Eisenberger, R.; Ford, M.T.; Buffardi, L.C.; Stewart, K.A.; Adis, C.S. Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1854–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, I.; Şirin, M.S.; Baş, M. The mediating effect of work engagement on the relationship between work–family conflict and turnover intention and moderated mediating role of supervisor support during global pandemic. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, A.G.; Chang, C.C. The association between job insecurity and engagement of employees at work. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2019, 34, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Deng, H.; Li, Y. Enhancing a sense of competence at work by engaging in proactive behavior: The role of proactive personality. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 801–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.C.; Kuo, C.C. Internship performance and satisfaction in sports: Application of the proactive motivation model. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2016, 18, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. The measurement of well-being and other aspects of mental health. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, T.W.; Wang, W.C.; Chou, M.T.; Chang, C.C. Measurement of hospital workers’ job strain using the Chinese version of the job content questionnaire. J. Healthc. Manag. 2012, 13, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Heijden, B.I.; Van Vuuren, T.C.; Kooij, D.T.; de Lange, A.H. Tailoring professional development for teachers in primary education. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M. An investigation of the joint effects of organisational tenure and supervisor support on work–family conflict and turnover intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2009, 16, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, A.; Den Hartog, D.N.; Belschak, F.D. Transformational leadership and proactive work behaviour: A moderated mediation model including work engagement and job strain. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 89, 588–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, D.M.; Schroeder, T.D.; Martinez, H.A. Proactive personality at work: Seeing more to do and doing more? J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crant, J.M. The proactive personality scale and objective job performance among real estate agents. J. Appl. Psychol. 1995, 80, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Schaufeli, W.B. A cross-national study of work engagement as a mediator between job resources and proactive behaviour. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Xu, Q.; Xin, X.; Cui, X.; Ji, M.; You, X. How can proactive personality affect cabin attendants’ safety behaviors? The moderating roles of social support and safety climate. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Li, F.; Rao, Z.; Yang, Y. The effect of proactive personality on college students’ career decision-making difficulties: Moderating and mediating effects. J. Adult Dev. 2021, 28, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Lee, Y.H. Understanding sport coaches’ turnover intention and well-being: An environmental psychology approach. Psychol. Health 2022, 37, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Crant, J.M.; Kraimer, M.L. Proactive personality and career success. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kang, H.S.; Kim, E.J. The role of supervisor support on employees’ training and job performance: An empirical study. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2018, 42, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surujlal, J.; Dhurup, M. Antecedents predicting coaches’ intentions to remain in sport organisations. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 16, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, K. Rethinking job characteristics in work stress research. Hum. Relat. 2006, 59, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, E.G.; Kirby, S.L.; Lewis, M.A. A study of the effectiveness of training proactive thinking. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 1538–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Driscoll, M.P.; Beehr, T.A. Supervisor behaviors, role stressors and uncertainty as predictors of personal outcomes for subordinates. J. Organ. Behav. 1994, 15, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajuria, G.; Khan, N. Perceived organisational support and employee engagement: A literature review. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 1366–1384. [Google Scholar]

- Ployhart, R.E.; Vandenberg, R.J. Longitudinal research: The theory, design, and analysis of change. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 94–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Sprigg, C.A. Minimizing strain and maximizing learning: The role of job demands, job control, and proactive personality. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | - | - | |||||||

| 2. Age | 39.85 | 9.06 | −0.17 * | ||||||

| 3. Education level | 2.36 | 0.53 | 0.08 | 0.10 | |||||

| 4. Tenure | 10.13 | 8.31 | −0.02 | 0.76 * | 0.09 | ||||

| 5. Proactive personality | 5.90 | 0.78 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.04 | |||

| 6. Work engagement | 5.51 | 1.12 | −0.21 * | 0.25 * | −0.04 | 0.24 * | 0.40 * | ||

| 7. Perceived work competence | 5.80 | 0.82 | −0.20 * | 0.19 * | −0.00 | 0.19 * | 0.41 * | 0.67 * | |

| 8. Perceived supervisor support | 5.40 | 1.51 | −0.03 | −0.11 | −0.13 * | −0.10 | 0.20 * | 0.34 * | 0.22 * |

| Variable | Work Engagement | Perceived Work Competence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Sex | −0.19 * | −0.18 * | −0.19 * | −0.19 * | −0.07 | −0.08 |

| Age | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.01 |

| Education level | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Tenure | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Proactive personality | 0.38 * | 0.40 * | 0.18 * | |||

| Work engagement | 0.65 * | 0.57 * | ||||

| R2 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.45 | 0.48 |

| Adj R2 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.44 | 0.47 |

| F | 7.41 * | 16.92 * | 5.30 * | 15.60 * | 41.95 * | 38.82 * |

| df | 4, 256 | 5, 255 | 4, 256 | 5, 255 | 5, 255 | 6, 254 |

| Variable | Work Engagement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Sex | −0.19 * | −0.17 * | −0.17 * |

| Age | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Education level | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Tenure | 0.18 | 0.17 * | 0.17 * |

| Proactive personality | 0.33 * | 0.29 * | |

| Perceived supervisor support | 0.30 * | 0.30 * | |

| Proactive personality × Perceived supervisor support | −0.15 * | ||

| R2 | 0.10 * | 0.33 * | 0.35 * |

| ΔR2 | 0.23 * | 0.02 * | |

| Variable | Perceived Work Competence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Sex | −0.19 * | −0.07 | −0.07 |

| Age | 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| Education level | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Tenure | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Work engagement | 0.65 * | 0.69 * | |

| Perceived supervisor support | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| Work engagement × Perceived supervisor support | 0.11* | ||

| R2 | 0.08 * | 0.45 * | 0.46 * |

| ΔR2 | 0.38 * | 0.01 * | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, S.-H.; Lu, W.-C.; Chen, Y.-C.; Wu, M.-H. The Relationships among Proactive Personality, Work Engagement, and Perceived Work Competence in Sports Coaches: The Moderating Role of Perceived Supervisor Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912707

Lin S-H, Lu W-C, Chen Y-C, Wu M-H. The Relationships among Proactive Personality, Work Engagement, and Perceived Work Competence in Sports Coaches: The Moderating Role of Perceived Supervisor Support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912707

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Shin-Huei, Wan-Chen Lu, Yi-Chieh Chen, and Ming-Han Wu. 2022. "The Relationships among Proactive Personality, Work Engagement, and Perceived Work Competence in Sports Coaches: The Moderating Role of Perceived Supervisor Support" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912707

APA StyleLin, S.-H., Lu, W.-C., Chen, Y.-C., & Wu, M.-H. (2022). The Relationships among Proactive Personality, Work Engagement, and Perceived Work Competence in Sports Coaches: The Moderating Role of Perceived Supervisor Support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912707