A Qualitative Systematic Review of Access to Substance Use Disorder Care in the United States Criminal Justice System

Abstract

1. Introduction

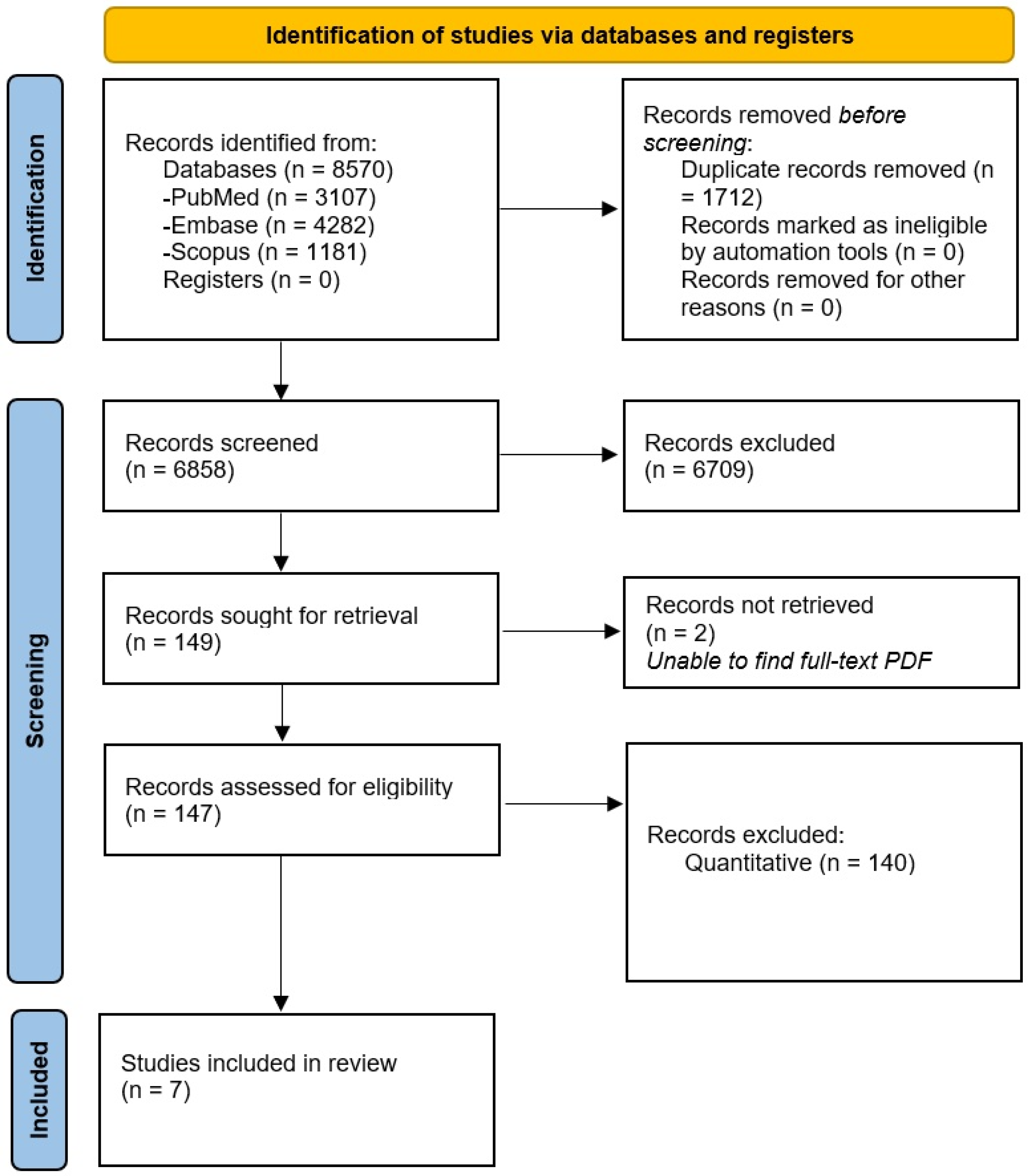

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Qualitative Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Managing Withdrawal from Medication-Assistant Treatment

3.2. Facilitators and Barriers to Treatment Programs in the Criminal Justice System

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Appendix of Strategies

Appendix A.1. PubMed/MEDLINE Search Strategy

Appendix A.2. Embase Search Strategy

Appendix A.3. Scopus Search Strategy

References

- Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- World Prison Brief. World Prison Population List Issue. Available online: http://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/wppl_12.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- U.S. Department of Justice. Behind Bars II: Substance Abuse and America’s Prison Population. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/behind-bars-ii-substance-abuse-and-americas-prison-population (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Probation and Parole in the United States, 2017–2018. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/probation-and-parole-united-states-2017-2018 (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Jail Inmates in 2020—Statistical Tables. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/jail-inmates-2020-statistical-tables#:~:text=At%20midyear%202020%2C%20inmates%20ages,100%2C000%20persons)%20at%20midyear%202020 (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- American Civil Liberties Union. Over-Jailed and Un-Treated. Available online: https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/20210625-mat-prison_1.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Komalasari, R.; Wilson, S.; Haw, S. A systematic review of qualitative evidence on barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of opioid agonist treatment (OAT) programmes in prisons. Int. J. Drug Policy 2021, 87, 102978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatsco, A.J.; Champagne-Langabeer, T.; Holder, T.F.; Stotts, A.L.; Langabeer, J.R. Developing interagency collaboration to address the opioid epidemic: A scoping review of joint criminal justice and healthcare initiatives. Int. J. Drug Policy 2020, 83, 102849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malta, M.; Varatharajan, T.; Russell, C.; Pang, M.; Bonato, S.; Fischer, B. Opioid-related treatment, interventions, and outcomes among incarcerated persons: A systematic review. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1003002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britten, N.; Campbell, R.; Pope, C.; Donovan, J.; Morgan, M.; Pill, R. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: A worked example. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2002, 7, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 91-513, 84 Stat. 1236; United States Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 1970.

- Seers, K. Qualitative systematic reviews: Their importance for our understanding of research relevant to pain. Br. J. Pain 2015, 9, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronowitz, S.V.; Laurent, J. Screaming behind a door: The experiences of individuals incarcerated without medication-assisted treatment. J. Correct. Health Care 2016, 22, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awgu, E.; Magura, S.; Rosenblum, A. Heroin-dependent inmates’ experiences with buprenorphine or methadone maintenance. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2010, 42, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkley-Rubinstein, L.; Peterson, M.; Clarke, J.; Macmadu, A.; Truong, A.; Pognon, K.; Parker, M.; Marshall, B.D.L.; Green, T.; Martin, R.; et al. The benefits and implementation challenges of the first state-wide comprehensive medication for addictions program in a unified jail and prison setting. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 205, 107514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, J.; Kubiak, S.; Pasman, E.; Gaba, A.; Andre, M.; Smelson, D.; Pinals, D.A. Evaluating the implementation of a prisoner re-entry initiative for individuals with opioid use and mental health disorders: Application of the consolidated framework for implementation research in a cross-system initiative. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. [CrossRef]

- Matusow, H.; Dickman, S.L.; Rich, J.D.; Fong, C.; Dumont, D.M.; Hardin, C.; Marlowe, D.; Rosenblum, A. Medication assisted treatment in US drug courts: Results from a nationwide survey of availability, barriers and attitudes. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2013, 44, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.G.; Kelly, S.M.; Brown, B.S.; Reisinger, H.S.; Peterson, J.A.; Ruhf, A.; Agar, M.H.; Schwartz, R.P. Incarceration and opioid withdrawal: The experiences of methadone patients and out-of-treatment heroin users. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2009, 41, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.G.; Harmon-Darrow, C.; Lertch, E.; Monico, L.B.; Kelly, S.M.; Sorensen, J.L.; Schwartz, R.P. Views of barriers and facilitators to continuing methadone treatment upon release from jail among people receiving patient navigation services. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2021, 127, 108351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.; Cairns, J.; Churchill, D.; Cook, D.; Haynes, B.; Hirsh, J.; Irvine, J.; Levine, M.; Levine, M.; Nishikawa, J.; et al. Evidence-based medicine: A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA 1992, 268, 2420–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder 2020: Focused Update. Available online: https://sitefinitystorage.blob.core.windows.net/sitefinity-production-blobs/docs/default-source/guidelines/npg-jam-supplement.pdf?sfvrsn=a00a52c2_2 (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Sigmon, S.C.; Dunn, K.E.; Saulsgiver, K.; Patrick, M.E.; Badger, G.J.; Heil, S.H.; Brooklyn, J.R.; Higgins, S.T. A randomized, double-blind evaluation of buprenorphine taper duration in primary prescription opioid abusers. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 1347–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakko, J.; Svanborg, K.D.; Kreek, M.J.; Heilig, M. 1-year retention and social function after buprenorphine-assisted relapse prevention treatment for heroin dependence in Sweden: A randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2003, 361, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sees, K.L.; Delucchi, K.L.; Masson, C.; Rosen, A.; Clark, H.W.; Robillard, H.; Banys, P.; Hall, S.M. Methadone maintenance vs. 180-day psychosocially enriched detoxification for treatment of opioid dependence: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2000, 283, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordo, L.; Barrio, G.; Bravo, M.J.; Indave, B.I.; Degenhardt, L.; Wiessing, L.; Ferri, M.; Pastor-Barriuso, R. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ 2017, 357, j1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Treatment Improvement Protocol 44. September 2013. Available online: https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma13-4056.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Wakeman, S.E.; Barnett, M.L. Primary care and the opioid-overdose crisis—Buprenorphine myths and realities. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management. J. Addict. Med. 2020, 14 (Suppl. S1), 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, C.; Sivberg, B.; Willman, A.; Fagerström, C. A trajectory towards partnership in care—Patient experiences of autonomy in intensive care: A qualitative study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2015, 31, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabizadeh, C.; Jafari, S.; Momennasab, M. Patient’s dignity: Viewpoints of patients and nurses in hospitals. Hosp. Top. 2021, 99, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author and Year of Publication | Population | Methods: Interview (I) Focus Group (FG) Both: I and FG | Treatment: MAT: Methadone (M) Buprenorphine (B) Naltrexone (N) | Withdrawal | Limited Withdrawal | Facilitators and Barriers to MAT Programs | Locations | Number of Participants | Eligibility Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aronowitz et al., 2016 [13] | Formerly Incarcerated | I | M, B before incarceration | * | Methadone and buprenorphine outpatient treatment centers in northern New England | 10 | Incarceration, forced MAT taper, English speaker, 18 years or older | ||

| Awgu et al., 2011 [14] | Incarcerated | I | M, B | * | Key Extended Entry Program (KEEP) within the Rikers Island jail complex in New York City | 133 | Opioid use disorder and a sentence less than 1 year long | ||

| Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2019 [15] | Incarcerated | I | M, B, N | * | * | Rhode Island Department of Corrections MAT | 40 | MAT, 18 or older, able to speak and write in English | |

| Hanna et al., 2019 [16] | Stakeholders, providers, facility staff, policymakers | Both | Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC) | Not reported | Staff and participants at at Michigan department of correction MAT | ||||

| Matusow et al., 2013 [17] | People involved in drug courts | Neither: open ended question | 47 states plus D.C and Puerto Rico | 103 responses | Surveys sent to drug courts in 49 states plus D.C and Puerto Rico | ||||

| Mitchell et al., 2011 [18] | methadone maintenance program participant | I | M | * | * | Baltimore Maryland | 92 | In treatment group found at Baltimore methadone clinics. Out of treatment found through targeted sampling | |

| Mitchell et al. 2021 [19] | Incarcerated and post-release | I | M | * | Baltimore Maryland | 17 | Methadone treatment program in Baltimore receiving IM + PN services |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barenie, R.E.; Cernasev, A.; Jasmin, H.; Knight, P.; Chisholm-Burns, M. A Qualitative Systematic Review of Access to Substance Use Disorder Care in the United States Criminal Justice System. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12647. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912647

Barenie RE, Cernasev A, Jasmin H, Knight P, Chisholm-Burns M. A Qualitative Systematic Review of Access to Substance Use Disorder Care in the United States Criminal Justice System. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12647. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912647

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarenie, Rachel E., Alina Cernasev, Hilary Jasmin, Phillip Knight, and Marie Chisholm-Burns. 2022. "A Qualitative Systematic Review of Access to Substance Use Disorder Care in the United States Criminal Justice System" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12647. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912647

APA StyleBarenie, R. E., Cernasev, A., Jasmin, H., Knight, P., & Chisholm-Burns, M. (2022). A Qualitative Systematic Review of Access to Substance Use Disorder Care in the United States Criminal Justice System. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12647. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912647