Family-Friendly Policies: Extrapolating A Pathway towards Better Work Attitudes and Work Behaviors in Hong Kong

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Family-Friendly Policy

1.2. Hong Kong as a Case Study

1.3. Research Question: How Do Family-Friendly Policies Affect Work–Life Conflict?

2. Theory Building and Hypothesis Development

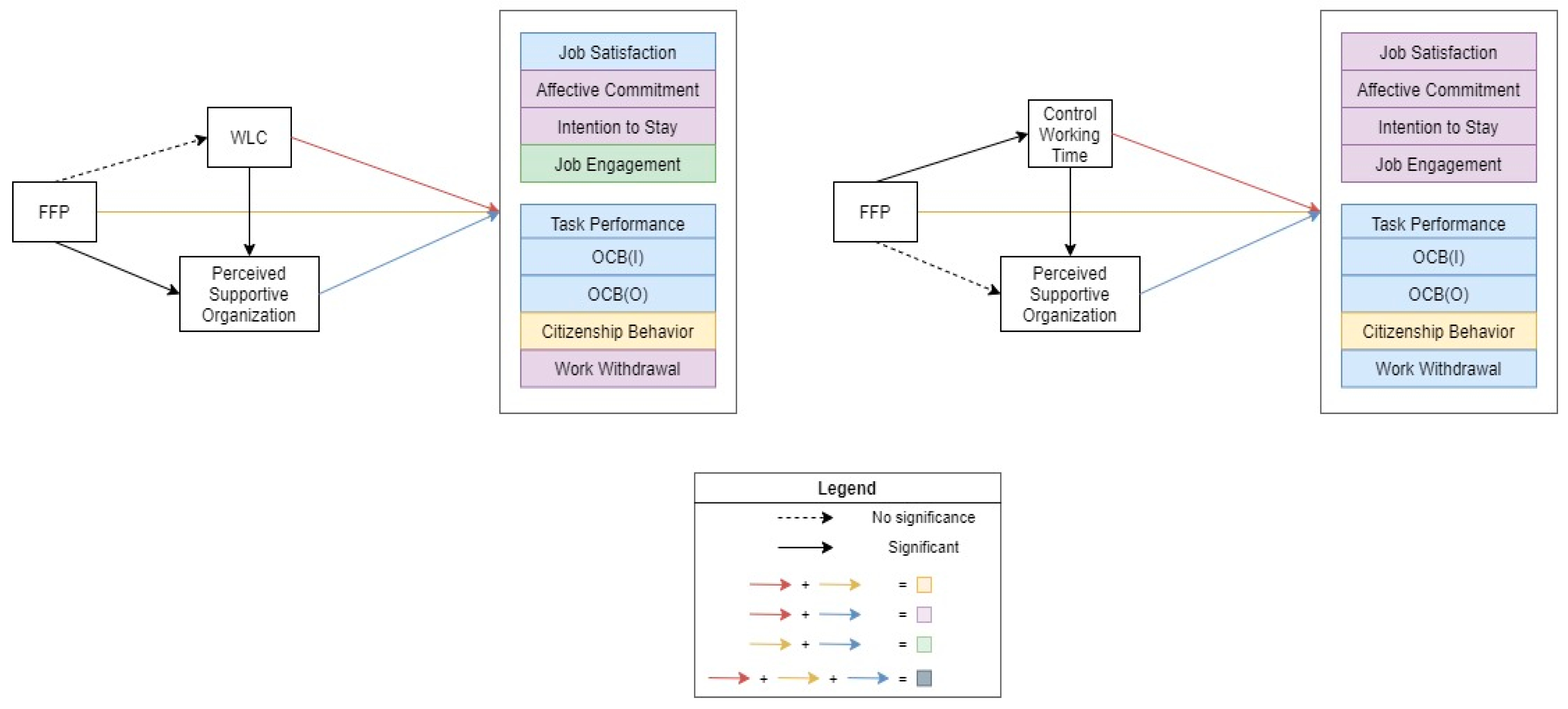

2.1. Signaling Theory: The Mediating Role of Work–Life Conflict and Perceived Organizational Support

2.2. Social Exchange Theory: The Moderating Role of Supportive Supervisors

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Analytical Strategy: PROCESS Macro

3.4. PROCESS Macro, Mediation, and Moderated Mediation

4. Results

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Census and Statistics Department of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. 2021 Report on Annual Earnings and Hours Survey. 2021. Available online: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/data/stat_report/product/B1050014/att/B10500142021AN21B0100.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- European Parliament. Directive 2003/88/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 November 2003 Concerning Certain Aspects of the Organisation of Working Time. 2003. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2003/88/oj (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Siu, O.L. Research on family-friendly employment policies and practices in Hong Kong: Implications for work–family interface. In Handbook of Research on Work–Life Balance in Asia; Lu, L., Cooper, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 181–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, H.; Lui, S. Gender differences in outcomes of work-family conflict: The case of Hong Kong managers. Sociol. Focus 2012, 32, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.M.; Russo, M.; Suñé, A.B.; Ollier-Malaterre, A. Outcomes of work–life balance on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and mental health: A study across seven cultures. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşdelen-Karçkay, A.; Bakalım, O. The mediating effect of work–life balance on the relationship between work–family conflict and life satisfaction. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2017, 26, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, M.K.; Stritch, J.M. Family-friendly policies, gender, and work–life balance in the public sector. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2017, 39, 422–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, N.; Chapman, J. Work-life balance and family friend policies. Evid. Base 2013, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, I.; Osoian, C.; Ratiu, P. The role of work-life balance practices in order to improve organizational performance. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2010, XIII, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.H. Is family-friendly policy (FFP) working in the private sector of South Korea? SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.-Y.; Roh, J. Balancing work and family in South Korea’s public organizations: Focusing on family-friendly policies in elementary school organizations. Public Pers. Manag. 2010, 39, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, A.G.; Overton, B.J.; Maniam, C.B. Flexible working arrangements, work life balance and women in Malaysia. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2015, 5, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, U. Combining career and care-giving: The impact of family-friendly policies on the well-being of working mothers in the United Kingdom. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2019, 38, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Hur, S.; Smith-Walter, A. Family-friendly work practices and job satisfaction and organizational performance. Public Pers. Manag. 2013, 42, 545–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltzstein, A.L.; Ting, Y.; Saltzstein, G.H. Work-family balance and job satisfaction: The impact of family-friendly policies on attitudes of federal government employees. Public Adm. Rev. 2001, 61, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D. Family-supportive work environments: The role of organizational perceptions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 58, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Bae, K.; Yang, G. The effects of family-friendly policies on job satisfaction and organizational commitment: A panel study conducted on South Korea’s public institutions. Public Pers. Manag. 2017, 46, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Lawler, J.J.; Shi, K. Implementing family-friendly employment practices in banking industry: Evidences from some African and Asian countries. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, J.; De Cieri, H.; Iverson, R.D. Costing turnover: Implications of work/ family conflict at management level. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 1998, 36, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Bae, K.; Goodman, D. The influence of family-friendly policies on turnover and performance in South Korea. Public Pers. Manag. 2014, 43, 520–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.H. Work-life balance: An exploratory analysis of family-friendly policies for reducing turnover intentions among women in U.S. Federal Law enforcement. Int. J. Public Adm. 2019, 42, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, O.L.; Lu, J.F.; Brough, P.; Lu, C.Q.; Bakker, A.B.; Kalliath, T.; O’Driscoll, M.; Phillips, D.R.; Chen, W.Q.; Lo, D.; et al. Role resources and work-family enrichment: The role of work engagement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Lian, Z. Skill Variety, Family-Friendly and Task Performance: The Moderation of Market Orientation. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Innovations in Economic Management and Social Science, Hangzhou, China, 15–16 April 2017; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, P.; Walumbwa, F.O. Family-friendly programs, organizational commitment, and work withdrawal: The moderating role of transformational leadership. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 397–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Research Office of the Legislative Council. Statistical Highlights: Working Hours in Hong Kong; ISSH06/19-20; The Research Office of the Legislative Council: Hong Kong, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Siu, O.L.; Cooper, C.L.; Roll, L.C.; Lo, C. Occupational stress and its economic cost in Hong Kong: The role of positive emotions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butts, M.M.; Casper, W.J.; Yang, T.S. How important are work-family support policies? A meta-analytic investigation of their effects on employee outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casper, W.J.; Harris, C.M. Work-life benefits and organizational attachment: Self-interest utility and signaling theory models. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 72, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job market signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suazo, M.M.; Martínez, P.G.; Sandoval, R. Creating psychological and legal contracts through HRM practices: A strength of signals perspective. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2011, 23, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, T.A.; Henry, L.C. Making the link between work-life balance practices and organizational performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2009, 19, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amah, O.E. Managing the negative effects of work-to-family and family-to-work conflicts on family satisfaction of working mothers in Nigeria: The role of extended family support. Community Work. Fam. 2019, 24, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.L.; Cheung, K.C.K. Family-friendly policies in the workplace and their effect on work-life conflicts in Hong Kong. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 3872–3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eversole, B.A.W.; Crowder, C.L. Toward a family-friendly academy: HRD’s role in creating healthy work-life cultural change interventions. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2020, 22, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Agrawal, P. Family-friendly practices in the organization: A citation analysis. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020, 40, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, J. Perceptions of work-family balance: How effective are family-friendly policies? Aust. J. Labour Econ. 2011, 14, 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, T.-Y.R.; Pang, K.K.; Tong, Y.J. Work Life Balance Survey of the Hong Kong Working Population 2010; The University of Hong Kong: Hong Kong, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes, B.B.; Briggs, T.E.; Huff, J.W.; Wright, J.A.; Neuman, G.A. Flexible and compressed workweek schedules: A meta-analysis of their effects on work-related criteria. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, D.F. How time-flexible work policies can reduce stress, improve health, and save money. Stress Health 2005, 21, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Justice in social exchange. Sociol. Inq. 1964, 34, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L.M.; Tetrick, L.E.; Taylor, M.S.; Coyle Shapiro, J.A.M.; Liden, R.C.; Parks, J.M.L.; Morrison, E.W.; Porter, L.W.; Robinson, S.L.; Roehling, M.V.; et al. The employee-organization relationship: A timely concept in a period of transition. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 23, 291–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L.M.; Bommer, W.H.; Rao, A.N.; Seo, J. Social and economic exchange in the employee/organization relationship: The moderating role of reciprocation wariness. J. Manag. Psychol. 2009, 24, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.T.; Ganster, D.C. Impact of family-supportive work variables on work-family conflict and strain: A control perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 1995, 80, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, E.W.; Thompson, C.A.; Kopelman, R.E. Rationale and construct validity evidence for a measure of perceived organizational family support (POFS): Because purported practices may not reflect reality. Community Work. Fam. 2003, 6, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, L.B.; Kossek, E.E.; Anger, W.K.; Bodner, T.; Zimmerman, K.L. Clarifying work-family intervention processes: The roles of work-family conflict and family-supportive supervisor behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.; Jabeen, S.; Ahmad, J. Moderated mediation between work life balance and employee job performance: The role of psychological wellbeing and satisfaction with coworkers. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 34, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A. Connecting work-family policies to supportive work environments. Group Organ. Manag. 2009, 34, 206–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Chu, C.W.L.; Kim, T.-Y.; Ryu, S. Family-supportive work environment and employee work behaviors. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 792–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, S.; Agus, M.; Lasio, D.; Serri, F. Development and validation of a measure of work-family interface. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 34, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, E.; Krone, K. “The policy exists but you can’t really use it”: Communication and the structuration of work-family policies. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2002, 30, 50–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, L.; Lee, S.Y.; Chou, K.L. Utilization of family friendly policies in Hong Kong. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 2893–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camman, C.; Fichman, M.; Jenkins, D.; Klesh, J. The Michigan Organizational Effectiveness Questionnaire; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J.; Smith, C. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 538–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Stassen, M.; Ursel, N.D. Perceived organizational support, career satisfaction, and the retention of older workers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, F.; Wu, A.M.S. Older workers’ successful aging and intention to stay. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 28, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Cropanzano, R. The mediating effects of social exchange relationships in predicting workplace outcomes from multifoci organizational justice. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2002, 89, 925–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, W.E.; Simpson, D.D. Employee substance use and on-the-job behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 1992, 77, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, F.Y.L.; Tang, C.S.K. The effect of emotional dissonance and emotional intelligence on work-family interference. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2012, 44, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Boles, J.S.; McMurrian, R. Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bagger, J.; Li, A. How does supervisory family support influence employees’ attitudes and behaviors? A social exchange perspective. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1123–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Omar, Z.; Silong, A.D.; Azim, A.M. Work-family psychological contract, job autonomy and organizational commitment. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2012, 9, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ko, J.; Hur, S. The impacts of employee benefits, procedural justice, and managerial trustworthiness on work attitudes: Integrated understanding based on social exchange theory. Public Adm. Rev. 2014, 74, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt-Catsouphes, M.; Bankert, E. Conducting a work/life workplace assessment. Compens. Benefits Manag. 1998, 14, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, N.; Proctor-Thomson, S.B.; Plimmer, G. The role of “voice” in matters of “choice”: Flexible work outcomes for women in the New Zealand public services. J. Ind. Relat. 2012, 54, 182–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, M. Creating the Family Friendship Workplace: Barriers to Solutions; Psychosocial Press: Hove, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.A.; Beauvais, L.L.; Lyness, K.S. When work-family benefits are not enough: The influence of work-family culture on benefit utilization, organizational attachment, and work-family conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 54, 392–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcour, M.; Batt, R. Work-Life Integration: Challenges and Organizational Responses. In It’s about Time: Couple and Careers; Moen, P., Ed.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 310–331. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel, S.K.; Olswang, S.; She, N. Childbirth, tenure, and promotion for women faculty. Rev. High. Educ. 1994, 17, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobel, S.A.; Kossek, E. Human resource strategies to support diversity in work and personal lifestyles: Beyond the “family-friendly” organization. In Managing Diversity: Human Resource Strategies for Transforming the Workplace; Kossek, E.E., Lobel, S.A., Eds.; Blackwell Business: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mcdermott, A.M.; Conway, E.; Rousseau, D.M.; Flood, P.C. Promoting effective psychological contracts through leadership: The missing link between HR strategy and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 52, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Chen, Z.X. Leader-member exchange in a Chinese context: Antecedents, the mediating role of psychological empowerment and outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, E.L.; Kossek, E.E.; Hammer, L.B.; Durham, M.; Bray, J.; Chermack, K.; Murphy, L.A.; Kaskubar, D. Getting there from here: Research on the effects of work–family initiatives on work–family conflict and business outcomes. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2008, 2, 305–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, W.J.; Buffardi, L.C. Work-life benefits and job pursuit intentions: The role of anticipated organizational support. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 65, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work–life conflict | 23.87 | 10.58 | (0.93) | ||||||||||||||

| Perceived control over working hours | 12.19 | 4.07 | 0.04 | (0.86) | |||||||||||||

| Perceived family-supportive organization | 26.15 | 9.15 | −0.05 | 0.26 * | (0.94) | ||||||||||||

| Supervisory family support | 9.35 | 2.43 | −0.36 * | 0.20 ** | 0.37 * | (0.86) | |||||||||||

| Number of family-friendly policies available | 4.13 | 3.21 | 0.10 * | 0.35 ** | 0.28 * | 0.03 | |||||||||||

| Number of family-friendly policies used before | 2.55 | 2.20 | 0.05 | 0.36 ** | 0.26 * | 0.09 | 0.83 ** | ||||||||||

| Job satisfaction | 11.66 | 2.76 | −0.25 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.16 * | 0.24 * | 0.05 | 0.07 | (0.77) | ||||||||

| Affective commitment | 28.46 | 7.83 | −0.10 | 0.30 ** | 0.33 * | 0.33 * | 0.16 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.59 ** | (0.92) | |||||||

| Intention to stay | 7.26 | 2.38 | −0.26 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.27 * | 0.38 * | 0.14 ** | 0.13 * | 0.58 ** | 0.77 ** | (0.90) | ||||||

| Job engagement | 29.07 | 9.20 | −0.11 * | 0.22 ** | 0.36 * | 0.26 * | 0.18 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.44 ** | (0.95) | |||||

| Task performance | 18.46 | 3.20 | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.11 * | 0.16 * | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.34 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.23 ** | (0.94) | ||||

| OCB(I) | 19.96 | 5.24 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.13 * | 0.15 * | −0.05 | −0.01 | 0.23 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.10 * | 0.29 ** | 0.40 ** | (0.90) | |||

| OCB(O) | 17.93 | 5.76 | −0.04 | 0.09 | 0.21 * | 0.12 * | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.26 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.58 ** | (0.91) | ||

| Citizenship behavior | 12.98 | 3.77 | −0.04 | 0.11 * | 0.07 | 0.15 * | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.31 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.48 ** | (0.86) | |

| Work withdrawal | 11.16 | 4.55 | 0.18 ** | −0.02 | −0.18 * | −0.16 * | −0.03 | −0.07 | −0.50 ** | −0.45 ** | −0.43 ** | −0.47 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.20 ** | (0.84) |

| Work–Life Conflict (WLC) | Perceived Supportive Organization (PSO) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | |||||||||||

| FFP | a1 | −0.007 | 0.1171 | 0.952 | a2 | 0.26 * | 0.1 | 0.01 | |||||||||

| WLC | d21 | −0.1 * | 0.04 | 0.02 | |||||||||||||

| PSO | |||||||||||||||||

| Constant | iM1 | 3.61 | 0.07 | <0.001 | iM2 | 4.18 | 0.17 | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Job Satisfaction | Affective Commitment | Intention to Stay | Job Engagement | ||||||||||||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | |||||

| FFP | c’ | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.27 * | 0.1 | 0.007 | ||||

| WLC | b1 | −0.19 | 0.09 | 0.49 | −0.16 * | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.19 * | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.054 | ||||

| PSO | b2 | 0.11 * | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.2 * | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.18 * | 0.37 | <0.001 | 0.34 * | 0.05 | <0.001 | ||||

| Constant | iY | 5.52 | 0.24 | <0.001 | 4.2 | 0.21 | <0.001 | 3.37 | 0.2 | <0.001 | 3.11 | 0.25 | <0.001 | ||||

| Task Performance | OCB(I) | OCB(O) | Citizenship Behavior | Work Withdrawal | |||||||||||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | ||

| FFP | C’ | −0.13 | 0.08 | 0.11 | −0.07 | 0.07 | 0.3 | −0.06 | 0.07 | 0.43 | −0.16 * | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.035 | 0.06 | 0.54 | |

| WLC | b1 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.014 | 0.03 | 0.663 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.69 | 0.07 * | 0.02 | 0.004 | |

| PSO | b2 | 0.09 * | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.09 * | 0.03 | 0.006 | 0.16 * | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.69 | −0.93 * | 0.28 | 0.008 | |

| Constant | iY | 5.45 | 0.21 | <0.001 | 3.11 | 0.18 | <0.001 | 2.6 | 0.19 | <0.001 | 3.48 | 0.2 | <0.001 | 2.5 | 0.15 | <0.001 | |

| Control over Working Time (CWT) | Perceived Supportive Organization (PSO) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | |||||||||||

| FFP | a1 | 0.42 * | 0.06 | <0.001 | a2 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.48 | |||||||||

| CWT | d21 | 0.44 * | 0.09 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||

| PSO | |||||||||||||||||

| Constant | iM1 | 2.6 | 0.35 | <0.001 | iM2 | 2.68 | 0.24 | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Job Satisfaction | Affective Commitment | Intention to Stay | Job Engagement | ||||||||||||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | |||||

| FFP | c’ | −0.17 | 0.1 | 0.09 | −0.008 | 0.09 | 0.93 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.74 | 0.19 | 0.1 | 0.06 | ||||

| CWT | b1 | 0.26 * | 0.09 | 0.002 | 0.33 * | 0.07 | <0.001 | 0.29 * | 0.07 | <0.001 | 0.18 * | 0.09 | 0.04 | ||||

| PSO | b2 | 0.1 * | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.18 * | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.17 * | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.32 * | 0.05 | <0.001 | ||||

| Constant | iY | 4.16 | 0.25 | <0.001 | 2.9 | 0.22 | <0.001 | 1.98 | 0.21 | <0.001 | 2.4 | 0.27 | <0.001 | ||||

| Task Performance | OCB(I) | OCB(O) | Citizenship Behavior | Work Withdrawal | |||||||||||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | ||

| FFP | c’ | −0.1 | 0.09 | 0.25 | −0.1 | 0.07 | 0.17 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.28 | −0.23 * | 0.08 | 0.005 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.64 | |

| CWT | b1 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.29 | 0.19 * | 0.07 | 0.007 | 0.02 | 0.053 | 0.71 | |

| PSO | b2 | 0.1 * | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.08 * | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.15 * | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.35 | −0.11 * | 0.03 | <0.001 | |

| Constant | iY | 5.48 | 0.22 | <0.001 | 3.03 | 0.18 | <0.001 | 2.5 | 0.2 | <0.001 | 3.02 | 0.21 | <0.001 | 2.7 | 0.16 | <0.001 | |

| Work–Life Conflict | Control over Working Time | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | |

| FFP | a1 | −0.9 | 0.62 | 0.13 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.11 |

| SS (Supportive Supervisors) | f1 | −0.80 * | 0.11 | <0.001 | 0.19 * | 0.05 | 0.005 |

| FFP * SS | f2 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.12 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.79 |

| Constant | iM1 | 6.25 | 0.37 | <0.001 | 1.94 | 0.19 | <0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vyas, L.; Cheung, F.; Ngo, H.-Y.; Chou, K.-L. Family-Friendly Policies: Extrapolating A Pathway towards Better Work Attitudes and Work Behaviors in Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912575

Vyas L, Cheung F, Ngo H-Y, Chou K-L. Family-Friendly Policies: Extrapolating A Pathway towards Better Work Attitudes and Work Behaviors in Hong Kong. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912575

Chicago/Turabian StyleVyas, Lina, Francis Cheung, Hang-Yue Ngo, and Kee-Lee Chou. 2022. "Family-Friendly Policies: Extrapolating A Pathway towards Better Work Attitudes and Work Behaviors in Hong Kong" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912575

APA StyleVyas, L., Cheung, F., Ngo, H.-Y., & Chou, K.-L. (2022). Family-Friendly Policies: Extrapolating A Pathway towards Better Work Attitudes and Work Behaviors in Hong Kong. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912575