The Impact of COVID-19 on Maternal Mental Health during Pregnancy: A Comparison between Canada and China within the CONCEPTION Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

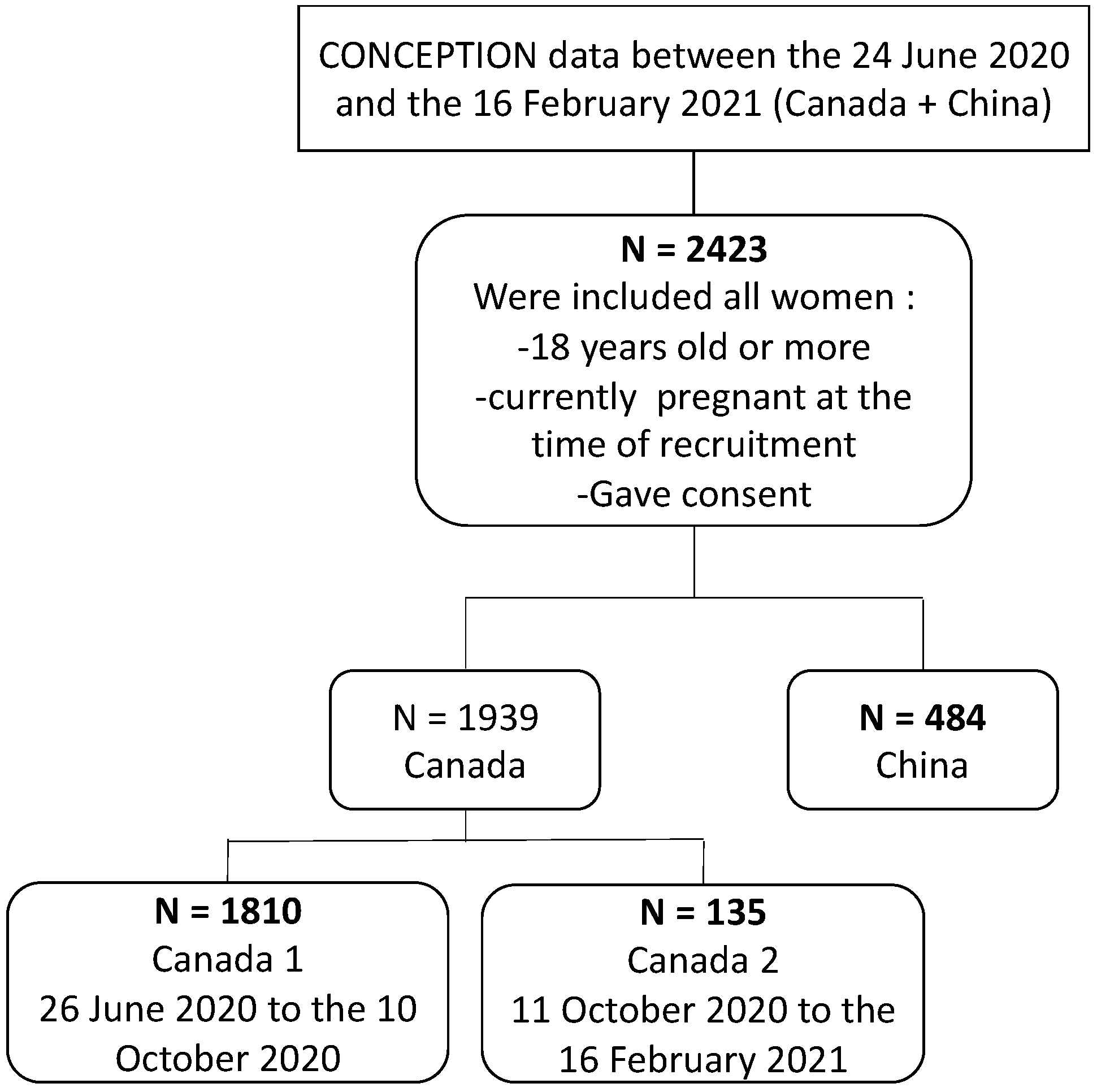

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

- (A)

- We first collected general maternal characteristics and health history (past history and since the start of pregnancy) in order to define our study groups in detail. These variables include: (1) general and socio-demographic information: gestational age (continuous), maternal age (continuous), pre-pregnancy height and weight to calculate the body mass index (continuous), ethnicity (Aboriginal, Asian, Black, Caucasian/white, Hispanic, other), annual household income (categorized as <$30,000, $30,000–$60,000, $60,001–$90,000, $90,001–$120,000, $120,001–$150,000, $150,000–$180,000 and >$180,000), years of education (continuous), living situation (with a partner, parents or family, alone), area of residence (urban, rural, suburban), country of residence (Canada, China); (2) Health behaviors including sports, smoking, alcohol and drug use (yes/no); (3) Comorbidities and medication use, including medications available over the counter (OTC); (4) Work/employment status and changes in status following the onset of the COVID-19 crisis and (5) Present experiences related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- (B)

- We collected data on COVID-19, to measure the positivity rate and familial impact of COVID-19 throughout the pandemic. These variables include: (1) COVID-19 testing (yes/no) and diagnosis by a positive test (yes/no) (2) Number of immediate or extended family member(s) and/or close friends tested positive for COVID-19.

- (C)

- We assessed the impact of the public health measures on the pregnancy experience and changes in birth plans related to the COVID-19 pandemic by collecting information on: (1) Support by primary prenatal care provider(s) and resources available, (2) Type of prenatal classes/information, (3) Support persons not permitted during delivery, (4) Family and friends not permitted in hospital, (5) Separation with newborns after delivery, (6) Concerns about breastfeeding, and (7) All concerns regarding changes in the birth plan and delivery related to COVID-19 were measured on a 4-category ordinal scale; possible responses were “not concerned at all”, “a little concerned”, “moderately concerned” and “very concerned”.

- (D)

- As a proxy for the hardships pregnant participants endured, we asked about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the: (1) financial situation, (2) family income, (3) daily routine, (4) food access, (5) medical health care access excluding mental health, (6) mental health treatment access, (7) access to family, extended family, and non-family social supports, and (8) work situation. Those variables were measured on a 4-category ordinal scale; possible responses were “no change”, “mild”, “moderate” and “severe”.

- (E)

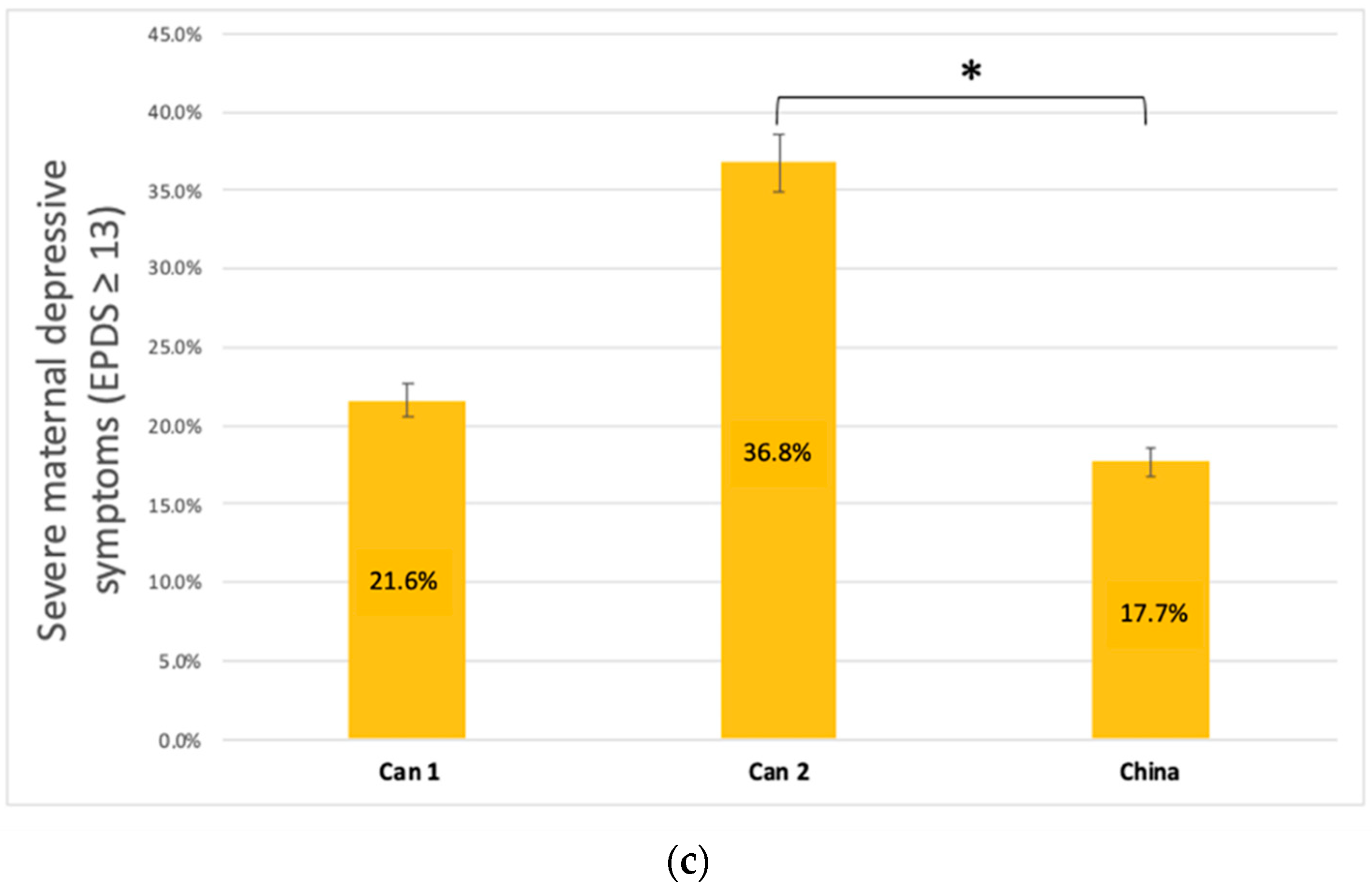

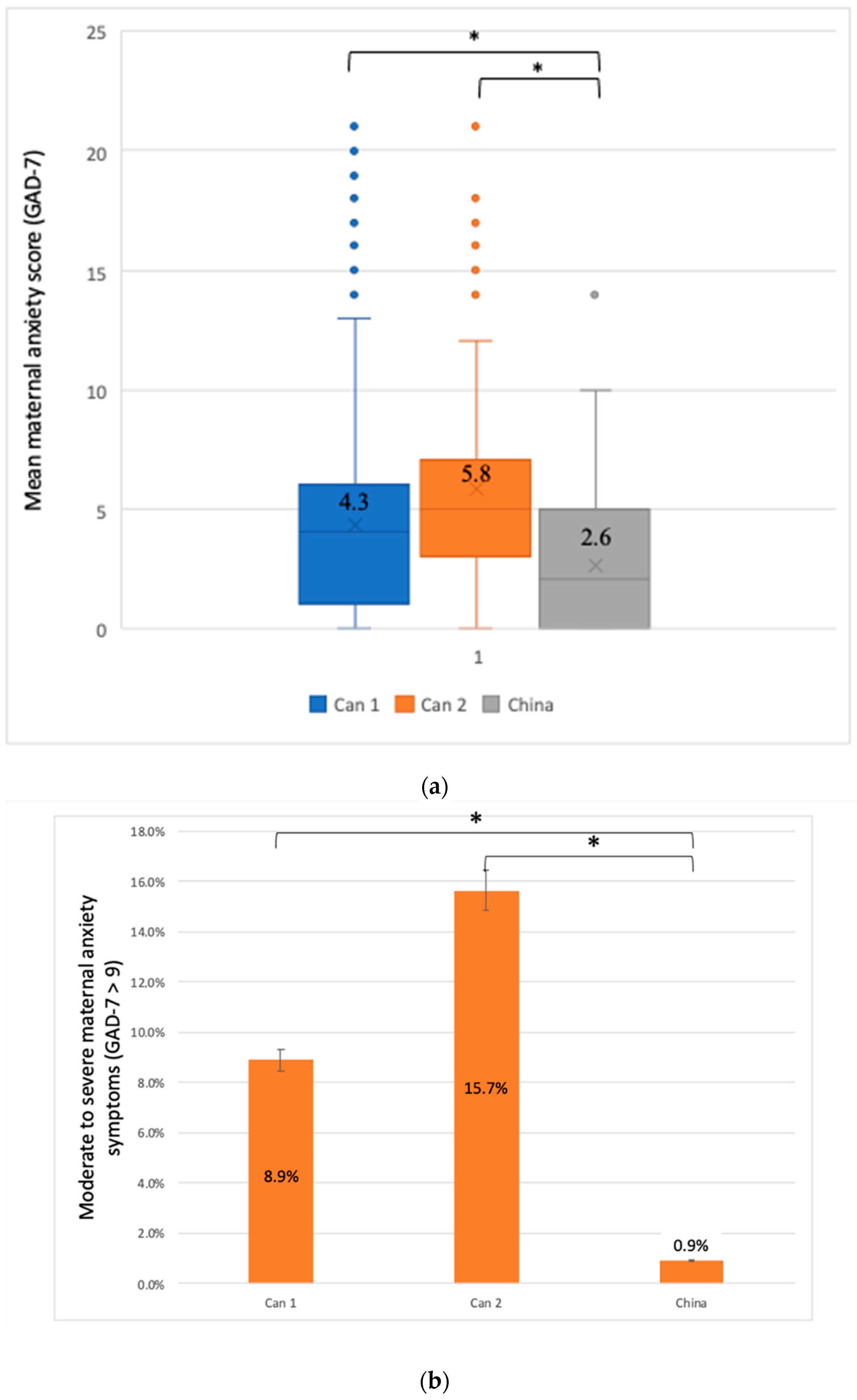

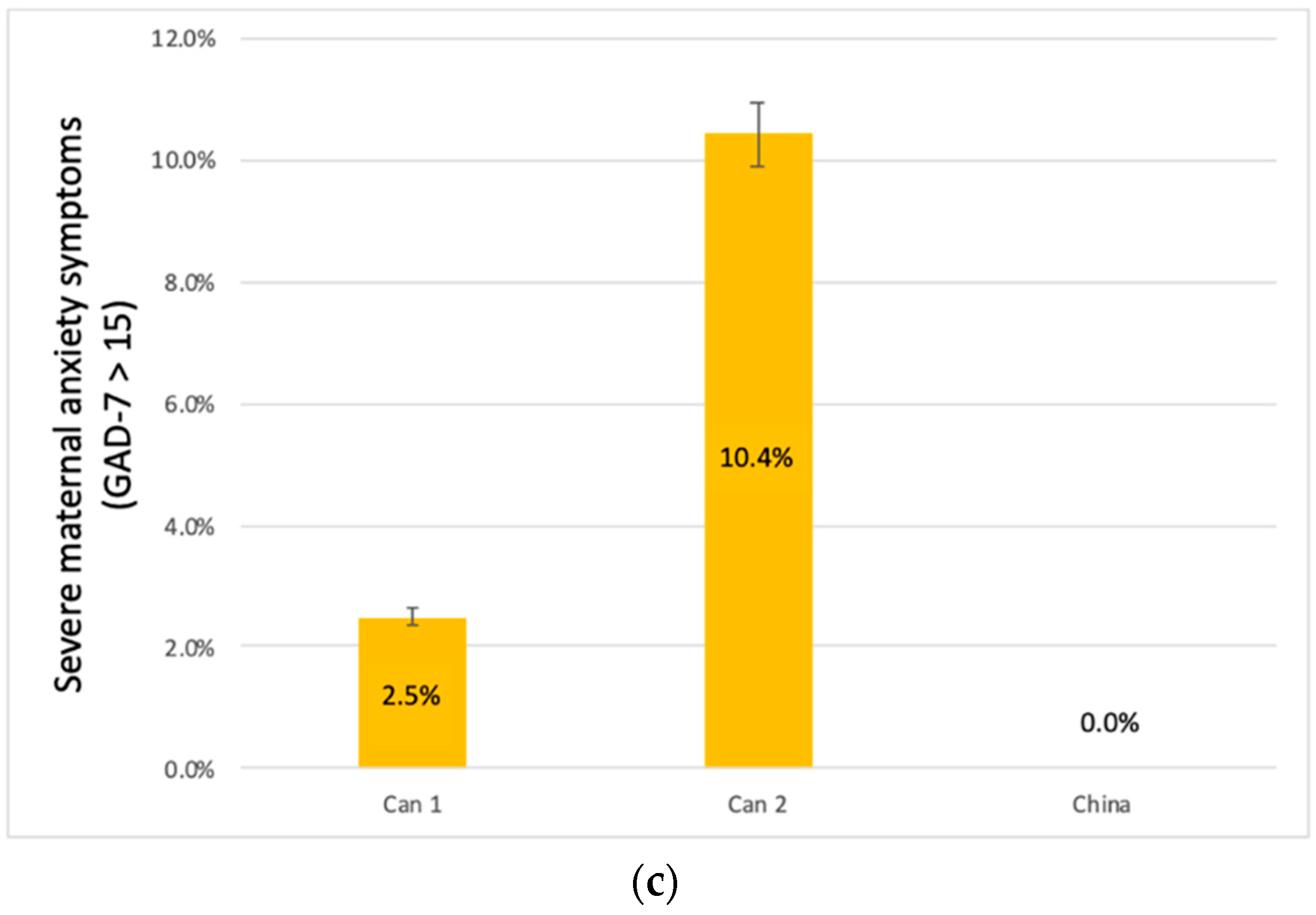

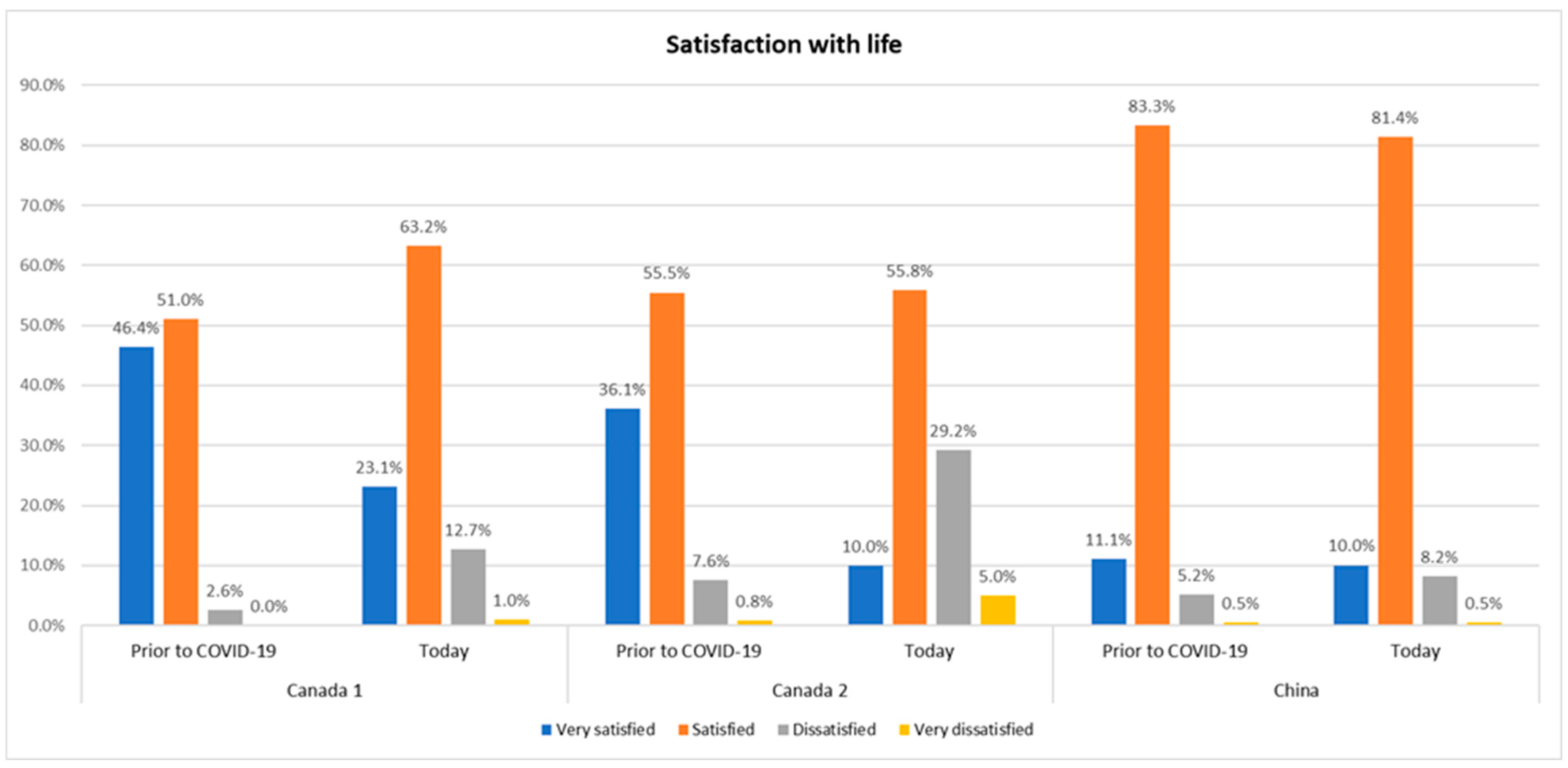

- We lastly assessed maternal mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic by measuring: (1) Maternal depression during the pandemic, using the Edinburgh Perinatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [58], (2) Anxiety during the pandemic, using the generalized anxiety disorders scale (GAD-7) [59], (3) Satisfaction with life, comparing the time prior to vs. since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic using a 4-category ordinal scale with responses ranging from “very satisfied” to “very unsatisfied” and (4) Stress due to this COVID-19 pandemic using a visual analog scale ranging from 0 (no stress) to 10 (maximum stress). We chose to use the EDPS and GAD-7 instruments to assess maternal mental health. The EDPS score has been validated in Mandarin, French and English [60,61,62]. This instrument is composed of 10 items. Each item poses a question and is scored from 0 to 3, and the total scores range from 0 to 30. With a cut-off value of ≥13 representing severe depression, this tool has a sensibility of 66% and a specificity of 95% for the screening of depression [63]. The GAD-7 scale has also been validated in Mandarin, English and French [64,65,66]. This instrument is comprised of 7 items, each item poses a question and is scored from 0 to 3 and the total score ranges from 0 to 21. With a cut-off value >9 representing moderate to severe anxiety, this score has a sensibility of 89% and a specificity of 82% for the screening of anxiety [67]. As such, we have categorized depression symptoms as continuous measure first and further classified as moderate to severe (if EPDS > 9) and severe (if EPDS ≥ 13) [22]. Similar to this, anxiety symptoms were classified as moderate to severe (if GAD-7 > 9), and severe (if GAD > 15) [23]. These cut-offs are determined by the tools themselves [22,23].

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Description of Participants

3.2. Maternal Mental Health—Depression, Anxiety, Stress Level and Satisfaction with Life

3.3. COVID Testing

3.4. COVID-19 Pandemic Concerns and Impacts on Pregnancy Experience

3.5. Impact of COVID-19 on Financial Situation and Daily Life

3.6. Predictors of Maternal Depression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lui, L.M.W.; Chen-Li, D.; Liao, Y.; Mansur, R.B.; Brietzke, E.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Ho, R.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Lipsitz, O.; et al. Government Response Moderates the Mental Health Impact of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Depression Outcomes across Countries. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 290, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Yang, H.; Ji, W.; Wu, W.; Chen, S.; Zhang, W.; Duan, G. Virology, Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Control of COVID-19. Viruses 2020, 12, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The Psychological Impact of Quarantine and How to Reduce It: Rapid Review of the Evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, C.; MacKinnon, A.; Bagshawe, M.; Tomfohr-Madsen, L.; Giesbrecht, G. Elevated Depression and Anxiety Symptoms among Pregnant Individuals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental Health and the COVID-19 Pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, R.; Agrawal, A.; Sharma, M. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Neurosci. Rural Pract. 2020, 11, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aknin, L.B.; Andretti, B.; Goldszmidt, R.; Helliwell, J.F.; Petherick, A.; De Neve, J.-E.; Dunn, E.W.; Fancourt, D.; Goldberg, E.; Jones, S.P.; et al. Policy Stringency and Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Analysis of Data from 15 Countries. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e417–e426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, F.; Sheehy, O.; Huneau, M.-C.; Chambers, C.; Fraser, W.D.; Johnson, D.; Kao, K.; Martin, B.; Riordan, S.H.; Roth, M.; et al. Impact of Maternal Prenatal and Parental Postnatal Stress on 1-Year-Old Child Development: Results from the OTIS Antidepressants in Pregnancy Study. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2016, 19, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.T.; Dancause, K.N.; Elgbeili, G.; Laplante, D.P.; King, S. Disaster-Related Prenatal Maternal Stress Explains Increasing Amounts of Variance in Body Composition through Childhood and Adolescence: Project Ice Storm. Environ. Res. 2016, 150, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punamäki, R.-L.; Diab, S.Y.; Isosävi, S.; Kuittinen, S.; Qouta, S.R. Maternal Pre- and Postnatal Mental Health and Infant Development in War Conditions: The Gaza Infant Study. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2018, 10, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, A.; Bowes, L.; Gardner, F. Modeling the Effects of War Exposure and Daily Stressors on Maternal Mental Health, Parenting, and Child Psychosocial Adjustment: A Cross-Sectional Study with Syrian Refugees in Lebanon. Glob. Ment. Health Camb. Engl. 2018, 5, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplante, D.P.; Brunet, A.; Schmitz, N.; Ciampi, A.; King, S. Project Ice Storm: Prenatal Maternal Stress Affects Cognitive and Linguistic Functioning in 5½-Year-Old Children. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 47, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplante, D.P.; Barr, R.G.; Brunet, A.; Galbaud du Fort, G.; Meaney, M.L.; Saucier, J.-F.; Zelazo, P.R.; King, S. Stress during Pregnancy Affects General Intellectual and Language Functioning in Human Toddlers. Pediatr. Res. 2004, 56, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplante, D.P.; Zelazo, P.R.; Brunei, A.; King, S. Functional Play at 2 Years of Age: Effects of Prenatal Maternal Stress. Infancy 2007, 12, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staneva, A.; Bogossian, F.; Pritchard, M.; Wittkowski, A. The Effects of Maternal Depression, Anxiety, and Perceived Stress during Pregnancy on Preterm Birth: A Systematic Review. Women Birth J. Aust. Coll. Midwives 2015, 28, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, R.; Dai, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Si, D.; Deng, T.; Xia, W. The Association between Symptoms of Depression during Pregnancy and Low Birth Weight: A Prospective Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérard, A.; Gorgui, J.; Tchuente, V.; Lacasse, A.; Gomez, Y.-H.; Côté, S.; King, S.; Muanda, F.; Mufike, Y.; Boucoiran, I.; et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic Impacted Maternal Mental Health Differently Depending on Pregnancy Status and Trimester of Gestation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Lv, L.; Zhang, J. Mental Health among Pregnant Women under Public Health Interventions during COVID-19 Outbreak in Wuhan, China. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 301, 113977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, H.; Li, N.; Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Cao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhou, A. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Symptoms in Pregnant Women before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 149, 110586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Duan, C.; Li, C.; Fan, J.; Li, H.; Chen, L.; Xu, H.; Li, X.; et al. Perinatal Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms of Pregnant Women during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak in China. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 223, 240.e1–240.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.J.P.; Wu, H.; He, Z.; Chan, N.-K.; Huang, J.; Wang, H.; Yin, Z.; Akinwunmi, B.; Ming, W.-K. Psychobehavioral Responses, Post-Traumatic Stress and Depression in Pregnancy during the Early Phase of COVID-19 Outbreak. Psychiatr. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 3, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.X.W.; Okeke, J.C.; Levitan, R.D.; Murphy, K.E.; Foshay, K.; Lye, S.J.; Knight, J.A.; Matthews, S.G. Evaluating Depression and Anxiety throughout Pregnancy and after Birth: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2022, 4, 100605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, J.E.; Atkinson, L.; Bennett, T.; Jack, S.M.; Gonzalez, A. Coping Strategies Mediate the Associations between COVID-19 Experiences and Mental Health Outcomes in Pregnancy. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2021, 24, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazanfarpour, M.; Bahrami, F.; Rashidi Fakari, F.; Ashrafinia, F.; Babakhanian, M.; Dordeh, M.; Abdi, F. Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression among Pregnant Women during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Meta-Analysis. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 43, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lok, K.Y.-W.; Ko, R.W.T.; Fan, H.S.L.; Wong, J.Y.; Choi, E.P.; Shek, N.W.M.; Ngan, H.Y.S.; Tarrant, M.; Li, J.; Huang, Y.; et al. International Survey on Fear and Childbirth Experience in Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Study Protocol. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e050132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, T. Dynamic Zero COVID Policy in the Fight against COVID. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, e58–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.; Li, J.; Cheng, Z.J. Zero-COVID Strategy: What’s Next? Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Lin, W.; Liu, P.; Zhang, M.; Huang, S.; Chen, C.; Li, Q.; Huang, W.; Zhong, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. Prevalence and Contributory Factors of Anxiety and Depression among Pregnant Women in the Post-Pandemic Era of COVID-19 in Shenzhen, China. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 291, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Ding, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. Epidemiology of COVID-19 in Jiangxi, China: A Retrospective Observational Study. Medicine 2021, 100, e27685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wn, L.; M, L.; J, L.; Yd, W.; J, W.; X, L. The Dynamic COVID-Zero Strategy on Prevention and Control of COVID-19 in China. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2022, 102, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19: Emergency Measures Tracker | McCarthy. Available online: https://www.mccarthy.ca/en/insights/articles/covid-19-emergency-measures-tracker (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Wang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Qu, F. The Potential Benefits of Chinese Integrative Medicine for Pregnancy Women during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Integr. Med. Res. 2020, 9, 100461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, C.; Marques, N. The Zero COVID Strategy Protects People, Economies and Freedoms more Effectively; Institut Économique Molinari: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, W.; Zeng, Z.; Dang, H.; Li, P.; Chuong, L.; Yue, D.; Wen, J.; Zhao, R.; Li, W.; Kominski, G. Towards Universal Health Coverage: Achievements and Challenges of 10 Years of Healthcare Reform in China. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Song, L.; Qiu, J.; Jing, W.; Wang, L.; Dai, Y.; Qin, G.; Liu, M. Reducing Maternal Mortality in China in the Era of the Two-Child Policy. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, J.G.; Park, A.L.; Dzakpasu, S.; Dayan, N.; Deb-Rinker, P.; Luo, W.; Joseph, K.S. Prevalence of Severe Maternal Morbidity and Factors Associated with Maternal Mortality in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e184571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada, Statistic Canada. Number of Maternal Deaths and Maternal Mortality Rates for Selected Causes. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310075601 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Tan, X.; Liu, X.; Shao, H. Healthy China 2030: A Vision for Health Care. Value Health Reg. Issues 2017, 12, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The SOGC Program for Prevention of Maternal Morbidity and Mortality—Canadian Foundation for Women’s Health. Available online: https://cfwh.org/womens-health/cfwh-program-for-prevention-of-maternal-morbidity-and-mortality/ (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Canada, P.H.A. of Care during Pregnancy: Family-Centred Maternity and Newborn Care National Guidelines. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/maternity-newborn-care-guidelines-chapter-3.html (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Keenan-Lindsay, L.; Yudin, M.H. No. 185-HIV Screening in Pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2017, 39, e54–e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Money, D.; Allen, V.M. The Prevention of Early-Onset Neonatal Group B Streptococcal Disease. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2016, 38, S326–S335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Guideline for Pre-Pregnancy Health Care Service (Trial); National Health Commission: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Hu, H.; Zhao, W.; Huang, A.; Yang, Q.; Di, J. Current Status of Antenatal Care of Pregnant Women—8 Provinces in China, 2018. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suivi de Grossesse: Les Visites et les Différents Tests à Passer. Available online: https://naitreetgrandir.com/fr/grossesse/trimestre1/grossesse-suivi-visites-tests-prenataux/ (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Tao, W.; Zeng, Z.; Dang, H.; Lu, B.; Chuong, L.; Yue, D.; Wen, J.; Zhao, R.; Li, W.; Kominski, G.F. Towards Universal Health Coverage: Lessons from 10 Years of Healthcare Reform in China. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T. Shanghai and Beijing Maternity Costs 2018. Pac. Prime Chinas Blog 2018. Available online: http://pacificprime.cn/blog/shanghai-beijing-maternity-costs-2018/ (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada Health. Care in Canada: Access Our Universal Health Care System. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/new-immigrants/new-life-canada/health-care/universal-system.html (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Guelfi, K.J.; Wang, C.; Dimmock, J.A.; Jackson, B.; Newnham, J.P.; Yang, H. A Comparison of Beliefs about Exercise during Pregnancy between Chinese and Australian Pregnant Women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying Lau RN Traditional Chinese Pregnancy Restrictions, Health-Related Quality of Life and Perceived Stress among Pregnant Women in Macao, China. Asian Nurs. Res. 2012, 6, 27–34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Cohen Silver, R.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary Research Priorities for the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Call for Action for Mental Health Science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, M.Z.; Limaye, R.J.; Omer, S.B.; O’Leary, S.T.; Ellingson, M.K.; Spina, C.I.; Brewer, S.E.; Chamberlain, A.T.; Bednarczyk, R.A.; Malik, F.; et al. Characterizing the Vaccine Knowledge, Attitudes, Beliefs, and Intentions of Pregnant Women in Georgia and Colorado. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceulemans, M.; Foulon, V.; Ngo, E.; Panchaud, A.; Winterfeld, U.; Pomar, L.; Lambelet, V.; Cleary, B.; O’Shaughnessy, F.; Passier, A.; et al. Mental Health Status of Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women during the COVID-19 Pandemic-A Multinational Cross-Sectional Study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajdy, A.; Feduniw, S.; Ajdacka, U.; Modzelewski, J.; Baranowska, B.; Sys, D.; Pokropek, A.; Pawlicka, P.; Kaźmierczak, M.; Rabijewski, M.; et al. Risk Factors for Anxiety and Depression among Pregnant Women during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Medicine 2020, 99, e21279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenko, A.; Agenagnew, L.; Beressa, G.; Tesfaye, Y.; Woldesenbet, Y.M.; Girma, S. COVID-19-Related Anxiety and Its Association with Dietary Diversity Score among Health Care Professionals in Ethiopia: A Web-Based Survey. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cina S di. The List of Blocked Websites in China in 2022—Latest News. Sapore di Cina. 2021. Available online: https://www.saporedicina.com/english/list-of-blocked-websites-in-china/ (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Shrestha, S.D.; Pradhan, R.; Tran, T.D.; Gualano, R.C.; Fisher, J.R.W. Reliability and Validity of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for Detecting Perinatal Common Mental Disorders (PCMDs) among Women in Low-and Lower-Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.A.; Zamorano, E.; García-Campayo, J.; Pardo, A.; Freire, O.; Rejas, J. Validity of the GAD-7 Scale as an Outcome Measure of Disability in Patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorders in Primary Care. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 128, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adouard, F.; Glangeaud-Freudenthal, N.M.C.; Golse, B. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in a Sample of Women with High-Risk Pregnancies in France. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2005, 8, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yin, L.; Chan, K.S.; Guo, X. Validation of the Mainland Chinese Version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in Chengdu Mothers. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of Postnatal Depression. Development of the 10-Item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levis, B.; Negeri, Z.; Sun, Y.; Benedetti, A.; Thombs, B.D. Accuracy of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for Screening to Detect Major Depression among Pregnant and Postpartum Women: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data. BMJ 2020, 371, m4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, X.; Shen, B.; Xian, J.; Ding, Y. Validation of the 7-Item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) as a Screening Tool for Anxiety among Pregnant Chinese Women. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 282, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Decker, O.; Müller, S.; Brähler, E.; Schellberg, D.; Herzog, W.; Herzberg, P.Y. Validation and Standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the General Population. Med. Care 2008, 46, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micoulaud-Franchi, J.-A.; Lagarde, S.; Barkate, G.; Dufournet, B.; Besancon, C.; Trébuchon-Da Fonseca, A.; Gavaret, M.; Bartolomei, F.; Bonini, F.; McGonigal, A. Rapid Detection of Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Major Depression in Epilepsy: Validation of the GAD-7 as a Complementary Tool to the NDDI-E in a French Sample. Epilepsy Behav. EB 2016, 57, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Li, W.; Sun, H.; Luo, X.; Garg, S.; Liu, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Mental Health Outcomes in Perinatal Women during the Remission Phase of COVID-19 in China. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 571876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäuerle, A.; Teufel, M.; Musche, V.; Weismüller, B.; Kohler, H.; Hetkamp, M.; Dörrie, N.; Schweda, A.; Skoda, E.-M. Increased Generalized Anxiety, Depression and Distress during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study in Germany. J. Public Health Oxf. Engl. 2020, 42, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäuerle, A.; Graf, J.; Jansen, C.; Dörrie, N.; Junne, F.; Teufel, M.; Skoda, E.-M. An E-Mental Health Intervention to Support Burdened People in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic: CoPE It. J. Public Health Oxf. Engl. 2020, 42, 647–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S. Social Relationships and Health. Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.C.; Letourneau, N.; Campbell, T.S.; Giesbrecht, G.F.; Apron Study Team. Social Buffering of the Maternal and Infant HPA Axes: Mediation and Moderation in the Intergenerational Transmission of Adverse Childhood Experiences. Dev. Psychopathol. 2018, 30, 921–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lautarescu, A.; Craig, M.C.; Glover, V. Prenatal Stress: Effects on Fetal and Child Brain Development. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2020, 150, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiki, S.; Avison, W.R.; Speechley, K.N.; Campbell, M.K. Determinants of Maternal Antenatal State-Anxiety in Mid-Pregnancy: Role of Maternal Feelings about the Pregnancy. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 196, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, L.E.; Gelaye, B.; Sanchez, S.E.; Williams, M.A. Association of Social Support and Antepartum Depression among Pregnant Women. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 264, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkel Schetter, C. Psychological Science on Pregnancy: Stress Processes, Biopsychosocial Models, and Emerging Research Issues. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2011, 62, 531–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesbrecht, G.F.; Poole, J.C.; Letourneau, N.; Campbell, T.; Kaplan, B.J.; APrON Study Team. The Buffering Effect of Social Support on Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Function during Pregnancy. Psychosom. Med. 2013, 75, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard-Gran, M.; Tambs, K.; Opjordsmoen, S.; Skrondal, A.; Eskild, A. Depression during Pregnancy and after Delivery: A Repeated Measurement Study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2004, 25, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, A.; Yin, J.; Waqas, A.; Bai, X.; Wang, D.; Rahman, A.; Li, X. Prevalence of Perinatal Depression and Its Determinants in Mainland China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 1022–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. Distribution of Total Income by Census Family Type and Age of Older Partner, Parent or Individual. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/cv.action?pid=1110001201 (accessed on 1 June 2022).

| Total N = 2423 | Canada 1 N = 1804 | Canada 2 N = 135 | China N = 484 | p-Value + CA1/Ch | p-Value + CA2/Ch | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at recruitment (mean, SD), years | 31.6 ± 4.4 | 31.9 ± 4.3 | 33.6 ± 4.2 | 30.2 ± 4.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 21 | 7 | 1 | 13 | ||

| Gestational age at recruitment (mean, SD), weeks | 26.2 ± 9.9 | 24.7 ± 9.8 | 20.7 ± 9.5 | 33.3 ± 7.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 11 | 3 | - | 8 | ||

| Pre-pregnancy body mass index, kg/m2–(mean, SD) | 24.9 ± 5.6 | 25.4 ± 5.7 | 26.0 ± 6.2 | 22.2 ± 4.0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 96 | 15 | 0 | 81 | ||

| Trimester of pregnancy at the time of survey completion | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| 1st trimester | 357 (14.8) | 305 (16.9) | 36 (26.7) | 16 (3.3) | ||

| 2nd trimester | 776 (32.1) | 670 (37.2) | 64 (47.4) | 42 (8.8) | ||

| 3rd trimester | 1278 (53.1) | 826 (45.9) | 35 (25.9) | 417 (87.8) | ||

| Missing value | 11 | 3 | - | 8 | ||

| Prenatal care follow-up * | ||||||

| Family physician | 712 (27.2) | 658 (33.2) | 45 (22.6) | 9 (1.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Obstetrician | 1632 (62.4) | 1090 (55.0) | 80 (52.6) | 462 (96) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Midwife | 253 (9.7) | 225 (11.4) | 25 (16.4) | 3 (0.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Nurse Practitioner | 1 (0.04) | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 | - | - |

| No follow up | 16 (0.6) | 8 (0.4) | 1 (0.7) | 7 (1.5) | - | 0.014 |

| Missing | 6 | 1 | 0 | 5 | ||

| Years of education–(mean, SD) | 16.2 ± 4.4 | 16.8 ± 4.5 | 15.8 ± 6.10 | 14.4 ± 3.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 96 | 61 | 4 | 31 | ||

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed | 1797 (78.2) | 1430 (82.9) | 105 (80.8) | 262 (59.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Self-employed | 193 (8.4) | 151 (8.8) | 12 (9.2) | 30 (6.8) | 0.18 | 0.33 |

| Student or Intern | 78 (3.4) | 62 (3.6) | 7 (5.4) | 9 (2.0) | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| Unemployed | 196 (8.5) | 49 (2.8) | 5 (3.8) | 142 (32.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| On welfare | 33 (1.4) | 32 (1.9) | 1 (0.8) | 0 | - | - |

| Prefer not to answer | 52 | 28 | 2 | 22 | ||

| Missing | 83 | 61 | 3 | 19 | ||

| Ethnic background | ||||||

| Aboriginal (North American Indians, Métis or Inuit [Inuk]) | 13 (0.6) | 11 (0.6) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.2) | - | - |

| Asian | 455 (19.6) | 29 (1.7) | 11 (8.5) | 415 (91.8) | ||

| Black | 20 (0.9) | 15 (0.9) | 5 (3.9) | - | ||

| Caucasian/White | 1714 (73.8) | 1608 (92.3) | 104 (80.6) | 2 (0.4) | ||

| Hispanic | 21 (0.9) | 20 (1.1) | 1 (0.8) | - | ||

| Other | 101 (4.3) | 11 (0.6) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 30 | 29 (1.7) | 11 (8.5) | 415 (91.8) | ||

| Missing | 79 | 15 (0.9) | 5 (3.9) | - | ||

| Living situation | <0.001 | 0.005 | ||||

| Living alone or single mother | 39 (1.7) | 34 (1.9) | 4 (3.1) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Living with a partner/married | 2260 (96.3) | 1700 (96.9) | 124 (94.7) | 436 (94.4) | ||

| Living with parents/family | 41 (1.7) | 16 (0.9) | 2 (1.5) | 23 (5.0) | ||

| Other | 7 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (0.4) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 5 | 4 | 1 | |||

| Missing | 71 | 46 | 4 | 21 | ||

| Area of residence | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Rural | 313 (13.4) | 256 (14.6) | 9 (6.9) | 48 (10.4) | ||

| Suburban | 837 (35.7) | 778 (44.5) | 52 (40.0) | 7 (1.5) | ||

| Urban | 1193 (50.9) | 716 (40.9) | 69 (53.1) | 408 (88.1) | ||

| Missing | 63 | 5 | 21 | 89 | ||

| Household income, CAN$ | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| <$30,000 | 259 (12.4) | 39 (2.3) | 7 (5.6) | 211(71.3) | ||

| $30,000–$60,000 | 234 (11.2) | 170 (10.1) | 15 (12.1) | 49(16.6) | ||

| $60,001–$90,000 | 305 (14.5) | 275 (16.4) | 15 (12.1) | 15 (5.1) | ||

| $90,001–$120,000 | 483 (23.0) | 444 (26.5) | 31 (25.0) | 8 (2.7) | ||

| $120,001–$150,000 | 333 (15.9) | 313 (18.7) | 14 (11.3) | 6 (2.0) | ||

| $150,000–$180,000 | 230 (11.0) | 207 (12.4) | 19 (15.3) | 4 (1.4) | ||

| >$180,000 | 253 (12.1) | 227 (13.6) | 23 (18.5) | 3 (1,0) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 252 | 81 | 8 | 163 | ||

| Missing | 75 | 48 | 3 | 24 | ||

| Total N = 2423 | Canada 1 N = 1804 | Canada 2 N = 135 | China N = 484 | p-Value + CA1/Ch | p-Value + CA2/Ch | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First pregnancy | ||||||

| Yes | 1069 (45.6) | 772 (44.0) | 60 (45.8) | 237 (51.6) | 0.003 | 0.24 |

| No | 1276 (54.4) | 983 (56.0) | 71 (54.2) | 222 (48.4) | ||

| Missing | 78 | 49 | 4 | 25 | ||

| Number of children to be born | ||||||

| Singleton (1 baby) | 2304 (98.5) | 1723 (98.6) | 126 (97.7) | 455 (98.7) | - | - |

| Twins (2 babies) | 30 (1.3) | 21 (1.2) | 3 (2.3) | 6 (1.3) | ||

| Multiple (more than 3 babies) | 4 (0.2) | 4 (0.2) | - | - | ||

| Missing | 85 | 56 | 6 | 23 | ||

| Current number of children | ||||||

| 0 | 1185 (50.9) | 903 (51.5) | 73 (55.7) | 209 (47.0) | 0.001 | 0.10 |

| 1 | 844 (36.2) | 608 (34.7) | 43 (32.8) | 193 (43.3) | ||

| ≥2 | 300 (12.9) | 242 (13.8) | 15 (11.5) | 43 (9.7) | ||

| Missing | 94 | 51 | 4 | 39 | ||

| COVID-19 Test | Canada 1 N = 1804 | Canada 2 N = 135 | China N = 484 | Total N = 2423 | p-Value + CA1/Ch | p-Value + CA2/Ch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | 1629 (90.4) | 79 (58.5) | 438 (91.8) | 2146 (88.9) | 0.34 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 173 (9.6) | 56 (41.5) | 39 (8.2) | 268 (11.1) | ||

| Positive (if tested) | 9 (5.1) | 4 (7.1) | 0 | 13 (4.8) | - | - |

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 7 | 9 | ||

| Number of immediate family members diagnosed with COVID-19 * | ||||||

| None | 1724 (96.8) | 123 (91.8) | 449 (99.8) | 2296 (97.1) | ||

| 1–5 | 56 (3.1) | 11 (8.2) | 1 (0.2) | 68 (2.9) | ||

| 6 or more | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.04) | ||

| No answer | 21 | 1 | 17 | 39 | ||

| Number of extended family members and/or close friends diagnosed with COVID-19 * | ||||||

| None | 1382 (77.6) | 83 (62.4) | 454 (99.6) | 1919 (81.0) | ||

| 1–5 | 388 (21.8) | 48 (36.1) | 2 (0.4) | 438 (18.5) | ||

| 6 or more | 11 (0.6) | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 13 (0.5) | ||

| No answer | 21 | 2 | 21 | 44 |

| Crude Odds Ratio (95%CI) | Adjusted * Odds Ratio (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort | ||

| Cohort Canada 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Cohort Canada 2 | 1.99 (1.36–2.91) | 1.31 (0.76–2.27) |

| Cohort China | 0.90 (0.72–1.13) | 3.20 (1.77–5.78) |

| Anxiety, GAD-7 score ** | 1.37 (1.32–1.42) | 1.32 (1.27–1.38) |

| Stress, scale (1–10) ** | 1.67 (1.58–1.76) | 1.64 (1.53–1.77) |

| Maternal age, years ** | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) |

| Body Mass Index, kg.m2 ** | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) |

| Weeks’ gestation, weeks ** | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| On welfare or unemployed | 1.08 (0.81–1.46) | 0.90 (0.56–1.45) |

| Household income, CAN$ | ||

| <$30,000 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| $30,001$60,000 | 1.62 (1.10–2.37) | 1.52 (0.82–2.83) |

| $60,001-$90,000 | 1.11 (0.77–1.60) | 1.04 (0.54–2.03) |

| $90,001-$120,000 | 1.70 (0.84–1.63) | 1.09 (0.57–2.09) |

| $120,001-$150,000 | 1.06 (0.74–1.51) | 0.99 (0.50–1.94) |

| >$150,000 | 0.76 (0.55–1.07) | 0.71 (0.37–1.37) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pagès, N.; Gorgui, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhao, J.-P.; Tchuente, V.; Lacasse, A.; Côté, S.; King, S.; Muanda, F.; et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on Maternal Mental Health during Pregnancy: A Comparison between Canada and China within the CONCEPTION Cohort. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12386. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912386

Pagès N, Gorgui J, Wang C, Wang X, Zhao J-P, Tchuente V, Lacasse A, Côté S, King S, Muanda F, et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on Maternal Mental Health during Pregnancy: A Comparison between Canada and China within the CONCEPTION Cohort. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12386. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912386

Chicago/Turabian StylePagès, Nicolas, Jessica Gorgui, Chongjian Wang, Xian Wang, Jin-Ping Zhao, Vanina Tchuente, Anaïs Lacasse, Sylvana Côté, Suzanne King, Flory Muanda, and et al. 2022. "The Impact of COVID-19 on Maternal Mental Health during Pregnancy: A Comparison between Canada and China within the CONCEPTION Cohort" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12386. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912386

APA StylePagès, N., Gorgui, J., Wang, C., Wang, X., Zhao, J.-P., Tchuente, V., Lacasse, A., Côté, S., King, S., Muanda, F., Mufike, Y., Boucoiran, I., Nuyt, A. M., Quach, C., Ferreira, E., Kaul, P., Winquist, B., O’Donnell, K. J., Eltonsy, S., ... Bérard, A. (2022). The Impact of COVID-19 on Maternal Mental Health during Pregnancy: A Comparison between Canada and China within the CONCEPTION Cohort. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12386. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912386