A Pilot Study to Examine the Feasibility and Acceptability of a Virtual Adaptation of an In-Person Adolescent Diabetes Prevention Program

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Conversion of Curriculum to Virtual Format

2.2. Feasibility Pilot

2.3. Virtual Teen HEED Pilot—Summer Cohort

2.4. Interviews and Recordings

3. Results

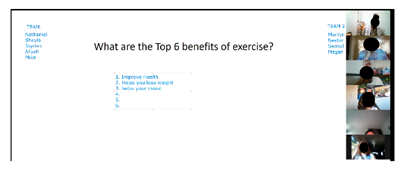

3.1. Creation of Virtual Teen HEED

3.2. Feasibility Pilot Session

“I think the breakout rooms were great. It gave you that feeling, I remember in person we did split up into groups and talk about it. So, I think the breakout rooms work great.”

“…I thought it was kind of annoying and it’s very inconvenient because you don’t really know who said ‘me’ first. Unless somebody is keeping strict tabs on who said ‘me’ first, it’s gonna get confusing. So maybe each question is a different number and whoever types that number first is the equivalent to saying ‘me’ first. Or you could just write out your name…”

“Maybe what we could do is use a word pertaining to the activity, so like ‘soda’ or ‘orange’ or the flavor of something for that specific activity. ‘Cause even as a peer leader looking on I’d have to check the time of when the response was given because I would look at 8 different ‘me(s)’ from everybody’s response and it can get a little bit confusing for the peer leader looking because I have to navigate between the PowerPoint, looking at you guys, and then looking at the chat, and manual.”

“On the Family Feud I think it’s really interesting because we got to work as a team as opposed to what most colleges do which is do a Kahoot and quiz people on information.”

“Doing the exercises in-person during the program there were yoga mats, and everything was prepared…everything was already available there for you to do the exercise so it was pretty easy. However, if you’re doing it on Zoom, then maybe you can try to accommodate the space, but not everyone has the space to layout, especially exercises you have to be on the floor for—that could be a bit difficult because maybe they can’t go to a more spacious area because their siblings are there or their parents are there and making a lot of noise as well.”

“To me it actually feels a little less awkward only because in-person everybody’s there, you can literally look at everybody right there, but on zoom you don’t notice typically because everybody is on a small screen at the top when you’re sharing the screen with the video. So, you’re not really seeing anybody else unless you’re actually looking up to the screen. So, I think it’s a bit better in terms of not wanting people to see you actually do the exercise.”

“It’s very hard to see each other so it’s very easy if you wanted to stop and not continue to do the exercises, you could get away with that, especially since there’s no one to see you.”

“Yes, I think [teens would come and do this online program] because it is very interactive and maybe now more than ever kids will want to interact not in a school setting.” (Referencing the social distancing measures due to the COVID-19 pandemic)

“I definitely think it would be a lot more convenient too. There were instances in the in-person program where some people couldn’t make it or lived too far, so I guess there would be a lot less of those types of instances, so most likely more people would show up. But there’s also the barrier of internet connection.”

3.3. Pilot of 12-Week Virtual Teen HEED Program

3.4. Overall Participant Feedback

“Healthy—portion planning, healthy plating, when I was at the doctor last Thursday, I lost a couple pounds.”

“Yes. I have been trying to get fit and I didn’t know a lot about diet until I came here. I don’t eat as much as I normally do. I started looking at the food labels. Very informative so I know what to do…”

“Thankful, helpful, grateful. I’m very grateful for this program to meet all of you and be part of something. It was not a waste of time. I would definitely do it [again].”

3.5. Peer Leaders

“They all get 5/5. The peer leaders were consistent with trying to keep us on our goals. It makes us feel better that someone is looking out for us. The peer leaders were funny. They don’t need to improve. The class had a super cool vibe. Look for vibrant, enthusiastic, fun, and happy people who radiate energy even if I’m not feeling it that day.”

3.6. General Comments about the Virtual Experience

“It’s alright on Zoom it would have been better in person. More physical. It was convenient but annoying.”

“I’m used to doing classes on Zoom. Zoom is good because it’s convenient. I have a busy schedule with school and work, so it was convenient.”

“The energy is not as it is in person. It’s a whole different type of vibe when we’re in person.”

“Cool to be on Zoom. Probably weird in person because it’s awkward meeting new people and doing something you have never done before. You don’t know what you’re walking into.”

3.7. Feedback about Specific Workshop Activities

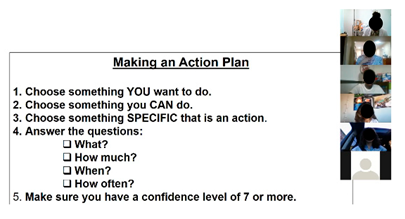

3.8. Making a Weekly Goal

“I could hang out with friends or do it at home or with family. It gave me the right mindset. When I wake up, I feel more healthy.”

“The action plans helped me. I knew what to do each day. It was helpful to know/plan what I was doing and for how long.”

3.9. Let’s Get Moving

“It was a good way to stay active and my uncle sometimes joined. It was more of a reason to exercise.”

“Sometimes I didn’t do it, sometimes I did. Sometimes I worked with my grandma or uncle. [The exercises] were not too hard, not too easy. Sometimes I made my own exercise. The [exercises] with the chair I would change and do like a burpee.”

“I didn’t follow the videos; I just did my own things. The videos didn’t look as intense. I wanted to do more intense workouts to get my body moving. When I first did it was ok but I liked my own thing better. I would change to more HIIT [high intensity interval training] cardio.”

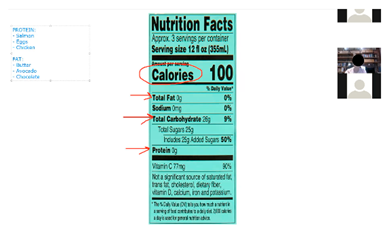

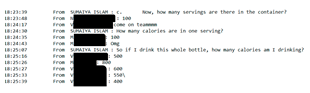

3.10. Nutrition Knowledge and Skills Building

“Now I know what to do when I get something. Before I was in the store, I didn’t care about the label, and I just drank or ate it. Sometimes I get Arizona so now I put it aside…Sometimes I remember to drink half and give the rest away.”

“…Helped me fix my eating habits, know what to eat and how much to eat and how much to save for later.”

“My grandma doesn’t know the way to plate a healthy plate, but I can tell her and [she] understands.”

“I didn’t know about it until this program. Every time I look at the plate at school cafeterias it’s like they are trying to lecture me. But now I know the reason that it’s there I can tolerate it.”

“I’m confident in using this method. I started eating less fats. I use this to measure out how I eat.”

3.11. Games

“I like brainstorming and competing. The first day was quiet but as soon as we got used to [the sessions]… it was educational but we were having fun.”

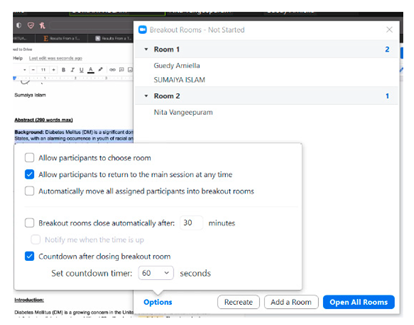

3.12. Zoom Breakout Rooms

“It was fun in the breakout rooms. I talked more with my peers. We got the chance to hear each other’s thoughts. After week 3 or 4 it was kind of always talkative. It depends who I was with [in the room].”

“At the beginning we were shy. But after we knew each other, we started brainstorming more—it was a process to confide in each other. Week 5/6 (like halfway) we became more comfortable…At the beginning I didn’t want to talk. It was helpful to keep the conversation. The team leader should pump up [the breakout room].”

“I didn’t like them at all unless you were with the peer leader because it was awkward, and you didn’t know anybody. Make sure that one peer leader is always there. Tell us if we don’t do the work we get points taken off.”

3.13. Using the Camera on Zoom

“I use my profile photo and it’s somewhat what I look like. I don’t like looking at myself in the camera or being too prideful. I guess I have low self-esteem.”

“I hate the camera. I couldn’t come on camera because I was always in public places/camera issues. But it does bring people together and makes you feel like you’re not being ignored. A compromise: maybe every week change the angle of the camera and then at the end have your face on camera.”

4. Discussion

Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020; pp. 12–15.

- Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Lawrence, J.M.; Dabelea, D.; Divers, J.; Isom, S.; Dolan, L.; Imperatore, G.; Linder, B.; Marcovina, S.; Pettitt, D.J.; et al. Incidence Trends of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes among Youths, 2002–2012. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menke, A.; Casagrande, S.; Cowie, C.C. Prevalence of Diabetes in Adolescents Aged 12 to 19 Years in the United States, 2005–2014. JAMA 2016, 316, 344–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabelea, D.; Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Saydah, S.; Imperatore, G.; Linder, B.; Divers, J.; Bell, R.; Badaru, A.; Talton, J.W.; Crume, T.; et al. Prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among children and adolescents from 2001 to 2009. JAMA 2014, 311, 1778–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andes, L.J.; Cheng, Y.J.; Rolka, D.B.; Gregg, E.W.; Imperatore, G. Prevalence of Prediabetes Among Adolescents and Young Adults in the United States, 2005–2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, e194498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, V.L.; Vangeepuram, N.; Fei, K.; Hanlen-Rosado, E.A.; Arniella, G.; Negron, R.; Fox, A.; Lorig, K.; Horowitz, C.R. Outcomes of a Weight Loss Intervention to Prevent Diabetes among Low-Income Residents of East Harlem, New York. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venditti, E.M.; Kramer, M.K. Diabetes Prevention Program community outreach: Perspectives on lifestyle training and translation. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44 (Suppl. 4), S339–S345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, R.; Ferretti, L.; Norwood, C.; Reich, D.; Chito-Childs, E.; McCallion, P.; Tiburcio, J.; McGee, E.; Lopez, J.A. Improving the Reach of the National Diabetes Prevention Program Within a Health Disparities Population: A Bronx New York Pilot Project Crossing Health- and Community-Based Sectors. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2016, 36, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruss, S.M.; Nhim, K.; Gregg, E.; Bell, M.; Luman, E.; Albright, A. Public Health Approaches to Type 2 Diabetes Prevention: The US National Diabetes Prevention Program and Beyond. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2019, 19, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, J.P.; Knowler, W.C.; Kahn, S.E.; Marrero, D.; Florez, J.C.; Bray, G.A.; Haffner, S.M.; Hoskin, M.; Nathan, D.M.; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The prevention of type 2 diabetes. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 4, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; You, W.; Almeida, F.; Estabrooks, P.; Davy, B. The Effectiveness and Cost of Lifestyle Interventions Including Nutrition Education for Diabetes Prevention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 404–421.e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangeepuram, N.; Williams, N.; Constable, J.; Waldman, L.; Lopez-Belin, P.; Phelps-Waldropt, L.; Horowitz, C.R. TEEN HEED: Design of a clinical-community youth diabetes prevention intervention. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2017, 57, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnet, D.; Plaut, A.; Courtney, R.; Chin, M.H. A practical model for preventing type 2 diabetes in minority youth. Diabetes Educ. 2002, 28, 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, C.R.; Buis, L.R.; Janney, A.W.; E Goodrich, D.; Sen, A.; Hess, M.L.; Mehari, K.S.; A Fortlage, L.; Resnick, P.J.; Zikmund-Fisher, B.J.; et al. An online community improves adherence in an internet-mediated walking program. Part 1: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2010, 12, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.C.; Niu, J. Evaluation of Internet-Based Interventions on Waist Circumference Reduction: A Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staffileno, B.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Fogg, L. Favorable Outcomes Using an eHealth Approach to Promote Physical Activity and Nutrition Among Young African American Women. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2018, 33, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackermann, R.T.; O’Brien, M.J. Evidence and Challenges for Translation and Population Impact of the Diabetes Prevention Program. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2020, 20, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, L.; de Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Labesse, M.; Nicklaus, S. Food choice motives and the nutritional quality of diet during the COVID-19 lockdown in France. Appetite 2021, 157, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokolo Anthony, J. Use of Telemedicine and Virtual Care for Remote Treatment in Response to COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Med. Syst. 2020, 44, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almufleh, A.; Givertz, M.M. Virtual Health During a Pandemic: Redesigning Care to Protect Our Most Vulnerable Patients. Circ. Heart Fail. 2020, 13, e007317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, M.M.; Burgermaster, M.; Mamykina, L. The use of social media in nutrition interventions for adolescents and young adults-A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018, 120, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quelly, S.B.; Norris, A.E.; DiPietro, J.L. Impact of mobile apps to combat obesity in children and adolescents: A systematic literature review. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2016, 21, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, S.R.; Raeside, R.; Singleton, A.; Hyun, K.; Redfern, J. Effectiveness of Text Message Interventions for Weight Management in Adolescents: Systematic Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e15849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xue, H.; Huang, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhang, D. A Systematic Review of Application and Effectiveness of mHealth Interventions for Obesity and Diabetes Treatment and Self-Management. Adv Nutr. 2017, 8, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamine, S.; Gerth-Guyette, E.; Faulx, D.; Green, B.B.; Ginsburg, A.S. Impact of mHealth chronic disease management on treatment adherence and patient outcomes: A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, D.A.; Gee, P.M.; Fatkin, K.J.; Peeples, M. A Systematic Review of Reviews Evaluating Technology-Enabled Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2017, 11, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, L.E.; Smith-Mason, C.E.; Corsica, J.A.; Kelly, M.C.; Hood, M.M. Remotely Delivered Interventions for Obesity Treatment. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2019, 8, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, K.M.J.; Koliwad, S.; Poon, T.; Xiao, L.; Lv, N.; Griggs, R.; Mummah, S. The Electronic CardioMetabolic Program (eCMP) for Patients With Cardiometabolic Risk: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, K.M.; Aurora, M.; Wang, E.J.; Muzaffar, A.; Pressman, A.; Palaniappan, L.P. Virtual small groups for weight management: An innovative delivery mechanism for evidence-based lifestyle interventions among obese men. Transl. Behav. Med. 2015, 5, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, T.H.; Chen, C.H.; Hsu, C.Y.; Chou, P.; Chiu, H.W. A pilot study of videoconferencing for an Internet-based weight loss programme for obese adults in Taiwan. J. Telemed. Telecare 2006, 12, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadheim, L.M.; McPherson, C.; Kassner, D.R.; Vanderwood, K.K.; Hall, T.O.; Butcher, M.K.; Helgerson, S.D.; Harwell, T.S. Adapted diabetes prevention program lifestyle intervention can be effectively delivered through telehealth. Diabetes Educ. 2010, 36, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, T.; Damschroder, L.J.; AuYoung, M.; Maciejewski, M.L.; Havens, K.; Ertl, K.; Vasti, E.; Weinreb, J.E.; Steinle, N.I.; Billington, C.J.; et al. Results From a Trial of an Online Diabetes Prevention Program Intervention. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taetzsch, A.; Gilhooly, C.H.; Bukhari, A.; Das, S.K.; Martin, E.; Hatch, A.M.; Silver, R.E.; Montain, S.J.; Roberts, S.B. Development of a Videoconference-Adapted Version of the Community Diabetes Prevention Program, and Comparison of Weight Loss With In-Person Program Delivery. Mil. Med. 2019, 184, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.K.; Brown, C.; Urban, L.E.; O’Toole, J.; Gamache, M.M.G.; Weerasekara, Y.K.; Roberts, S.B. Weight loss in videoconference and in-person iDiet weight loss programs in worksites and community groups. Obesity 2017, 25, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, D.S.; Stansbury, M.; Krukowski, R.A.; Harvey, J. Enhancing group-based internet obesity treatment: A pilot RCT comparing video and text-based chat. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2019, 5, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, B.; Hünnemeyer, K.; Sauer, H.; Hain, B.; Mack, I.; Schellberg, D.; Müller-Stich, B.P.; Weiner, R.; Meile, T.; Rudofsky, G.; et al. A 1-year videoconferencing-based psychoeducational group intervention following bariatric surgery: Results of a randomized controlled study. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2015, 11, 1349–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ptomey, L.T.; Willis, E.A.; Greene, J.L.; Danon, J.C.; Chumley, T.K.; Washburn, R.A.; Donnelly, J.E. The Feasibility of Group Video Conferencing for Promotion of Physical Activity in Adolescents With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 122, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.; Ritter, P.L.; Laurent, D.D.; Plant, K.; Green, M.; Jernigan, V.B.B.; Case, S. Online diabetes self-management program: A randomized study. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1275–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinski, A.A.; Anderson, R.A.; Vorderstrasse, A.A.; Fisher, E.B.; Pan, W.; Johnson, C.M. Type 2 Diabetes Education and Support in a Virtual Environment: A Secondary Analysis of Synchronously Exchanged Social Interaction and Support. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepah, S.C.; Jiang, L.; Peters, A.L. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into an Online Social Network: Validation against CDC Standards. Diabetes Educ. 2014, 40, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, H.J.; Rozenblum, R.; De La Cruz, B.A.; Orav, E.J.; Wien, M.; Nolido, N.V.; Metzler, K.; McManus, K.D.; Halperin, F.; Aronne, L.J.; et al. Effect of an Online Weight Management Program Integrated With Population Health Management on Weight Change: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 324, 1737–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansel, B.; Giral, P.; Gambotti, L.; Lafourcade, A.; Peres, G.; Filipecki, C.; Kadouch, D.; Hartemann, A.; Oppert, J.-M.; Bruckert, E.; et al. A Fully Automated Web-Based Program Improves Lifestyle Habits and HbA1c in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Abdominal Obesity: Randomized Trial of Patient E-Coaching Nutritional Support (The ANODE Study). J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Rhoon, L.; Byrne, M.; Morrissey, E.; Murphy, J.; McSharry, J. A systematic review of the behaviour change techniques and digital features in technology-driven type 2 diabetes prevention interventions. Digit. Health 2020, 6, 2055207620914427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.; Ritter, P.L.; Turner, R.M.; English, K.; Laurent, D.D.; Greenberg, J. A Diabetes Self-Management Program: 12-Month Outcome Sustainability From a Nonreinforced Pragmatic Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkow, T.M.; Vognild, L.K.; Johnsen, E.; Bratvold, A.; Risberg, M.J. Promoting exercise training and physical activity in daily life: A feasibility study of a virtual group intervention for behaviour change in COPD. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2018, 18, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosal, M.C.; Heyden, R.; Mejilla, R.; Capelson, R.; A Chalmers, K.; DePaoli, M.R.; Veerappa, C.; Wiecha, J.M.; Ershow, A.; Peterson, C. A Virtual World Versus Face-to-Face Intervention Format to Promote Diabetes Self-Management Among African American Women: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2014, 3, e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golovaty, I.; Wadhwa, S.; Fisher, L.; Lobach, I.; Crowe, B.; Levi, R.; Seligman, H. Reach, engagement and effectiveness of in-person and online lifestyle change programs to prevent diabetes. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1314. [Google Scholar]

- Toro-Ramos, T.; Michaelides, A.; Anton, M.; Karim, Z.; Kang-Oh, L.; Argyrou, C.; Loukaidou, E.; Charitou, M.M.; Sze, W.; Miller, J.D. Mobile Delivery of the Diabetes Prevention Program in People With Prediabetes: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e17842. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelides, A.; Major, J.; Pienkosz, E., Jr.; Wood, M.; Kim, Y.; Toro-Ramos, T. Usefulness of a Novel Mobile Diabetes Prevention Program Delivery Platform With Human Coaching: 65-Week Observational Follow-Up. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e93. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, A.; McDonald, J.C.; Brown, S.D.; Alexander, J.G.; Christian-Herman, J.L.; Fisher, S.; Quesenberry, C.P. Comparative Effectiveness of 2 Diabetes Prevention Lifestyle Programs in the Workplace: The City and County of San Francisco Diabetes Prevention Trial. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2020, 17, E38. [Google Scholar]

- Lorig, K.; Ritter, P.L.; Turner, R.M.; English, K.; Laurent, D.D.; Greenberg, J. Benefits of Diabetes Self-Management for Health Plan Members: A 6-Month Translation Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, K.T.; Ashley, A. Pilot study of a web-based intervention for adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J. Telemed Telecare 2013, 19, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, D.B.; Fellner, K.D.; Frank, M.; Small, M.; Hetherington, R.; Slater, R.; Daneman, D. Evaluation of an online education and support intervention for adolescents with diabetes. Soc. Work Health Care 2012, 51, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stinson, J.; Wilson, R.; Gill, N.; Yamada, J.; Holt, J. A systematic review of internet-based self-management interventions for youth with health conditions. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009, 34, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigden, A.; Anderson, E.; Linney, C.; Morris, R.; Parslow, R.; Serafimova, T.; Smith, L.; Briggs, E.; Loades, M.; Crawley, E. Digital Behavior Change Interventions for Younger Children With Chronic Health Conditions: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e16924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangeepuram, N.; Angeles, J.; Lopez-Belin, P.; Arniella, G.; Horowitz, C.R. Youth Peer Led Lifestyle Modification Interventions: A Narrative Literature Review. Eval. Program Plan. 2020, 83, 101871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New York University Furman Center. East Harlem Neighborhood Profile. Available online: https://furmancenter.org/neighborhoods/view/east-harlem (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Hinterland, K.; Naidoo, M.; King, L. Community Health Profiles 2018, Manhattan Community District 11: East Harlem; New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–20.

- Hill-Briggs, F.; Adler, N.E.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Chin, M.H.; Gary-Webb, T.L.; Navas-Acien, A.; Thornton, P.L.; Haire-Joshu, D. Social Determinants of Health and Diabetes: A Scientific Review. Diabetes Care 2020, 44, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. SAS Program for CDC Growth Charts. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/growthcharts/resources/sas.htm (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Anderson, M.; Jiang, J. Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Res. Cent. 2018, 31, 1673–1689. [Google Scholar]

- Goudeau, S.; Sanrey, C.; Stanczak, A.; Manstead, A.; Darnon, C. Why lockdown and distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to increase the social class achievement gap. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcclain, C.; Vogels, E.; Perrin, A.; Sechopoulos, S.; Rainie, L. The Internet and the Pandemic. Pew Res. Cent. 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/09/01/the-internet-and-the-pandemic/ (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- O’Connor, S.; Hanlon, P.; O’Donnell, C.A.; Garcia, S.; Glanville, J.; Mair, F.S. Understanding factors affecting patient and public engagement and recruitment to digital health interventions: A systematic review of qualitative studies. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 2016, 16, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanaboni, P.; Ngangue, P.; Mbemba, G.I.C.; Schopf, T.R.; Bergmo, T.S.; Gagnon, M.P. Methods to Evaluate the Effects of Internet-Based Digital Health Interventions for Citizens: Systematic Review of Reviews. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e10202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Velicer, W.F. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am. J. Health Promot. 1997, 12, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenstock, I.M.; Strecher, V.J.; Becker, M.H. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, C.L.M.; Peterson, E.; Havstad, S.; Johnson, C.C.; Hoerauf, S.; Stringer, S.; Gibson-Scipio, W.; Ownby, D.R.; Elston-Lafata, J.; Pallonen, U.; et al. A web-based, tailored asthma management program for urban African-American high school students. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Press, V.G.; Arora, V.M.; Kelly, C.A.; Carey, K.A.; White, S.R.; Wan, W. Effectiveness of Virtual vs. In-Person Inhaler Education for Hospitalized Patients with Obstructive Lung Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e1918205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Douma, M.; Maurice-Stam, H.; Gorter, B.; Houtzager, B.A.; Vreugdenhil, H.J.; Waaldijk, M.; Wiltink, L.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Scholten, L. Online psychosocial group intervention for adolescents with a chronic illness: A randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv. 2021, 26, 100447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigerland, S.; Ljótsson, B.; Thulin, U.; Öst, L.-G.; Andersson, G.; Serlachius, E. Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for children with anxiety disorders: A randomised controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 2016, 76, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Vigerland, S.; Serlachius, E.; Thulin, U.; Andersson, G.; Larsson, J.O.; Ljótsson, B. Long-term outcomes and predictors of internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety disorders. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 90, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staiano, A.E.; Beyl, R.A.; Guan, W.; Hendrick, C.A.; Hsia, D.S.; Newton, R.L., Jr. Home-based exergaming among children with overweight and obesity: A randomized clinical trial. Pediatr. Obes. 2018, 13, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, S.G.; Sundal, D.; Foster, G.D.; Lent, M.R.; Vojta, D. Effects of a pediatric weight management program with and without active video games a randomized trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2014, 168, 407–413. [Google Scholar]

- Nour, M.; Yeung, S.H.; Partridge, S.; Allman-Farinelli, M. A Narrative Review of Social Media and Game-Based Nutrition Interventions Targeted at Young Adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 735–752.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ptomey, L.T.; Washburn, R.A.; Goetz, J.R.; Sullivan, D.K.; Gibson, C.A.; Mayo, M.S.; Krebill, R.; Gorczyca, A.M.; Montgomery, R.N.; Honas, J.J.; et al. Weight Loss Interventions for Adolescents With Intellectual Disabilities: An RCT. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021050261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ptomey, L.T.; Lee, J.; White, D.A.; Helsel, B.C.; Washburn, R.A.; Donnelly, J.E. Changes in physical activity across a 6-month weight loss intervention in adolescents with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2021, 66, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C.L.; Sanderson, C.; Brown, B.J.; Andrén, P.; Bennett, S.; Chamberlain, L.R.; Davies, E.B.; Khan, K.; Kouzoupi, N.; Mataix-Cols, D.; et al. Opportunities and challenges of delivering digital clinical trials: Lessons learned from a randomised controlled trial of an online behavioural intervention for children and young people. Trials 2020, 21, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, L.; Hessler, D.; Naranjo, D.; Polonsky, W. AASAP: A program to increase recruitment and retention in clinical trials. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 86, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| In Person | Virtual Adaptation | Screen Shot |

|---|---|---|

| Charts with key workshop content made by leaders using flip charts based on samples in peer leader binder. | Create PowerPoint slides with all charts for hard copy and electronic binders for peer leaders and participants. Share slides in real-time during the virtual workshop session using screen share. |  |

| Write on flip charts for brainstorming, problem-solving, and other activities. | Utilize the “white-board” and annotation functions on Zoom to document ideas shared. |  |

| To set weekly goals, peer leaders walk around the room and assist participants with making their goal if needed. They then ask for a volunteer and go around the room to share plans. | Ask for a volunteer and then call on participants based on the order they are listed in the Zoom participant list. Participants may also choose to share their goal in the chat box with peer leaders prompting them for any information that is missing to make the goal as specific as possible or encouraging them to modify their goal so that they have a high confidence level that they can complete it. |  |

| Bring in, and share, food and drink labels. | Create PowerPoint slides with images of relevant nutrition labels for hard copy and electronic binders. Use screen share to share during workshop sessions. |  |

| “Let’s get moving” group exercise activity. | Share premade exercise videos using screen share and then spotlight a peer leader to model the exercises in real-time on camera to increase motivation and support. Plan modifications not only for different ability levels but also for teens with limited space to exercise. Create a library of videos for participants to use any time. |  |

| Use buzzer or hit the table when participants know answers to questions during interactive games. | Ask participants to type answers in the chat box to keep track of who gave the correct answer first and award points. |  |

| Divide the group into teams for games and small group activities. | Assign teams to breakout rooms for games and small group activities supervised by peer leaders and study staff. |  |

| Gender | Age | Race/Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 15 | Asian |

| Male | 13 | Latino |

| Male | 18 | Latino |

| Female | 13 | Latino |

| Female | 14 | Latino |

| Female | 15 | Black |

| Male | 14 | Latino |

| Male | 18 | Latino |

| Male | 15 | Black |

| Male | 13 | Black |

| Female | 17 | Black |

| Female | 13 | Latino |

| Male | 14 | Latino |

| Male | 13 | Latino |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Islam, S.; Elaiho, C.; Arniella, G.; Rivera, S.; Vangeepuram, N. A Pilot Study to Examine the Feasibility and Acceptability of a Virtual Adaptation of an In-Person Adolescent Diabetes Prevention Program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912286

Islam S, Elaiho C, Arniella G, Rivera S, Vangeepuram N. A Pilot Study to Examine the Feasibility and Acceptability of a Virtual Adaptation of an In-Person Adolescent Diabetes Prevention Program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912286

Chicago/Turabian StyleIslam, Sumaiya, Cordelia Elaiho, Guedy Arniella, Sheydgi Rivera, and Nita Vangeepuram. 2022. "A Pilot Study to Examine the Feasibility and Acceptability of a Virtual Adaptation of an In-Person Adolescent Diabetes Prevention Program" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912286

APA StyleIslam, S., Elaiho, C., Arniella, G., Rivera, S., & Vangeepuram, N. (2022). A Pilot Study to Examine the Feasibility and Acceptability of a Virtual Adaptation of an In-Person Adolescent Diabetes Prevention Program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912286