What Factors Affect Farmers’ Levels of Domestic Waste Sorting Behavior? A Case Study from Shaanxi Province, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Social Norms

2.2. Personal Norms

2.3. Group Identity

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. The Sample

3.2. Measurements of the Main Variables

3.3. Estimation Method

4. Results

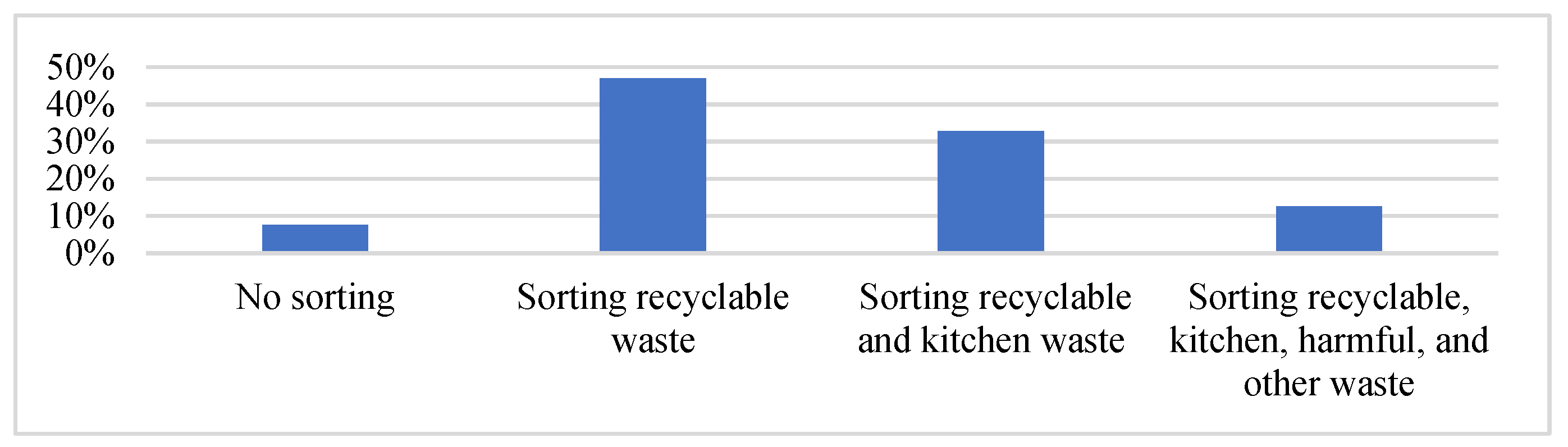

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. The Effects of Social and Personal Norms and Group Identity on the Level of Domestic Waste Sorting Behavior

4.3. Moderating Effect of Personal Norms

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Analysis of the Amount of Waste Generated in China’s Rural Areas, the Construction of Sanitation Facilities and the Investment in Rural Environmental Management in 2019. Available online: https://www.chyxx.com/industry/202101/923978.html (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhao, S.; Yang, S. Information publicity and resident’s waste separation behavior: An empirical study based on the norm activation model. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, C. COVID-19 waste management: Effective and successful measures in Wuhan, China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 163, 105071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.V.; Jiang, P.; Hemzal, M.; Klemeš, J.J. An update of COVID-19 influence on waste management. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkodie, S.A.; Owusu, P.A. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on waste management. Environ. Dev. Sustain 2021, 23, 7951–7960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Luo, X.; Zhang, J. Social supervision, group identity and farmers’ domestic waste centralized disposal behavior: An analysis baesd on mediation effect and regulation effect of the face concept. Chin. Rural Surv. 2019, 146, 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rada, E.C.; Ragazzi, M.; Fedrizzi, P. Web-GIS oriented systems viability for municipal solid waste selective collection optimization in developed and transient economies. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, M.; Yu, X.; Ren, H. What keeps Chinese from recycling: Accessibility of recycling facilities and the behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 109, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstad, A. Household food waste separation behavior and the importance of convenience. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardus, M.; Massoud, M.A. Predicting the intention to sort waste at home in rural communities in Lebanon: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, S.; Li, J.; Zhou, K. From intention to behavior: Comprehending residents’ waste sorting intention and behavior formation process. Waste Manag. 2020, 113, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; López-Mosquera, N.; Lera-López, F. Improving pro-environmental behaviours in Spain. The role of attitudes and socio-demographic and political factors. J. Environ. Pol. Plan 2016, 18, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Yang, W.; Shen, X. A comparison study of ‘motivation–intention–behavior’ model on household solid waste sorting in China and Singapore. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, Q.; Shen, X.; Chen, B.; Esfahani, S.S. The mechanism of household waste sorting behaviour—A study of Jiaxing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Wen, Z.G.; Chen, Y.X. College students’ municipal solid waste source separation behavior and its influential factors: A case study in Beijing, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Dang, S.; Luo, W.; Ji, K. Cultural consumption and knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding waste separation management in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldo, R.; Castro, P. The outer influence inside us: Exploring the relation between social and personal norms. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 112, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel, A.; Thøgersen, J. Activation of social norms in social dilemmas: A review of the evidence and reflections on the implications for environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psych. 2007, 28, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, C. Waste sorting in context: Untangling the impacts of social capital and environmental norms. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.R.; Doner, R.F. The new institutional economics, business associations, and development. Braz. J. Political Econ. 2022, 20, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Xu, K.; Si, H.; Song, L.; Duan, K. Investigating intention and behaviour towards sorting household waste in Chinese rural and urban–Rural integration areas. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashima, Y.; Paladino, A.; Margetts, E.A. Environmentalist identity and environmental striving. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiiuk, Y.; Liobikienė, G. The impact of informational, social, convenience and financial tools on waste sorting behavior: Assumptions and reflections of the real situation. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Bondy, K.; Schuitema, G. Listen to others or yourself? The role of personal norms on the effectiveness of social norm interventions to change pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 78, 101688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xu, C.; Zhu, Z.; Kong, B. How to encourage farmers to recycle pesticide packaging wastes: Subsidies VS social norms. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 133016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, M.; Nilsson, A.; Schultz, W.P. A meta-analysis of field-experiments using social norms to promote pro-environmental behaviors. Global Environ. Change 2019, 59, 101941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saphores, J.D.M.; Ogunseitan, O.A.; Shapiro, A.A. Willingness to engage in a pro-environmental behavior: An analysis of e-waste recycling based on a national survey of US households. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 60, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G.; Bartels, J. The norm activation model: An exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in pro-environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psych. 2013, 39, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanes, T. Personal norms in a globalized world: Norm-activation processes and reduced clothing consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obuobi, B.; Zhang, Y.; Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Nketiah, E.; Grant, K.G.; Adjei, M.; Cudjoe, D. Fruits and vegetable waste management behavior among retailers in Kumasi, Ghana. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Messina, A.; Tronu, G.; Limas, E.F.; Gupta, R.; Estrada, M. Personalized normative feedback and the moderating role of personal norms: A field experiment to reduce residential water consumption. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 686–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, P.C.; Maki, A.; Rothman, A.J. Promoting energy conservation behavior in public settings: The influence of social norms and personal responsibility. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of inter-group behavior. Psychol. Inter. Rel. 2004, 13, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Visschers, V.H.M.; Wickli, N.; Siegrist, M. Sorting out food waste behaviour: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, J.H.; Bamberg, S. Climate protection needs societal change: Determinants of intention to participate in collective climate action. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 44, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Xiaofeng, L.; Weizheng, Y.; Yanzhong, H.; Rongrong, L. Analysis of farmers’ participation behavior of village domin ecological governance: Based on identity, interpersonal and institutional three-dimensional perspectives. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2020, 29, 2805–2815. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistic of China (NBSC). Shaanxi Statistical Yearbook 2019, 1st ed.; China Statistical: Beijing, China, 2019; pp. 564–601.

- Dali County has Comprehensively Improved the Quality of Rural Ecological Environment 2019. Available online: http://www.weinan.gov.cn/news/gxdt/dlx/689058.htm (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Luo, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Z. The impacts of social interaction-based factors on household waste-related behaviors. Waste Manag. 2020, 118, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, K.D. Educational and Psychological Measurement and Evaluation, 1st ed.; ERIC: Bristol, UK, 1998; pp. 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Allcott, H.; Mullainathan, S. Behavior and energy policy. Science 2010, 327, 1204–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazhdani, D. Assessing the variables affecting on the rate of solid waste generation and recycling: An empirical analysis in Prespa Park. Waste Manag. 2016, 48, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis; Pearson Education India: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hage, O.; Söderholm, P.; Berglund, C. Norms and economic motivation in household recycling: Empirical evidence from Sweden. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2009, 53, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A.; Frijters, P. How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? Econ. J. 2004, 114, 641–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ling, M.; Lu, Y.; Shen, M. External influences on forming residents’ waste separation behaviour: Evidence from households in Hangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 63, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.Y.; Bowker, J.M.; Cordell, H.K. Ethnic variation in environmental belief and behavior: An examination of the New Ecological Paradigm in a social psychological context. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 157–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses, G.D.; Palacio, A.B. Recycling behavior: A multidimensional approach. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 837–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 106–108. [Google Scholar]

- Razali, F.; Daud, D.; Wengwai, C.; Jiram, W.R.A. Waste separation at source behaviour among Malaysian households: The Theory of Planned Behaviour with moral norm. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 271, 122025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, T.; Fritsche, I. Adherence to climate change-related ingroup norms: Do dimensions of group identification matter? Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 44, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udall, A.M.; de Groot, J.I.M.; De Jong, S.B.; Shankar, A. How I see me—A meta-analysis investigating the association between identities and pro-environmental behaviour. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gockeritz, S.; Schultz, P.W.; Rendon, T.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. Descriptive normative beliefs and conservation behavior: The moderating roles of personal involvement and injunctive normative beliefs. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variables | Measurement Items and Coding | Mean | S.D. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variables | |||||

| Level of DWSB | Domestic waste sorting behavior (DWSB) of respondents. No sorting = 0, Sorting recyclable waste = 1, Sorting recyclable and kitchen waste = 2, Sorting recyclable, kitchen, harmful, and other waste = 3 | 1.504 | 0.811 | 0 | 3 |

| Explanatory variables | |||||

| SN1 | Other farmers around you are sorting waste. Strongly disagree = 1, Disagree = 2, Neutral = 3, Agree = 4, Strongly agree = 5 | 1.630 | 0.495 | 1 | 5 |

| SN2 | You care a lot about the evaluation of other farmers. Strongly disagree = 1, Disagree = 2, Neutral = 3, Agree = 4, Strongly agree = 5 | 3.650 | 1.213 | 1 | 5 |

| PNs | According to the principal component analysis | 0.000 | 1.000 | −4.000 | 1.401 |

| GI | According to the principal component analysis | 0.000 | 1.000 | −3.334 | 1.454 |

| Control variables | |||||

| Gender | Gender of respondents. Male = 0, Female = 1 | 0.490 | 0.501 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | Age of respondents (years old) | 50.300 | 16.575 | 13 | 78 |

| Education | Education of respondents (years) | 8.260 | 3.582 | 0 | 17 |

| Gross annual income | Gross annual income of respondents’ household (Ten thousand RMB) | 3.329 | 3.706 | 0 | 40 |

| Marital status | Marital status of respondents. No = 0, Yes = 1 | 0.130 | 0.332 | 0 | 1 |

| Party membership | Party membership of respondents. No = 0, Yes = 1 | 0.090 | 0.289 | 0 | 1 |

| Items | Component Score Coefficient | |

|---|---|---|

| For each statement, please indicate how much you agree or disagree: Strongly disagree = 1, Disagree = 2, Neutral = 3, Agree = 4, Strongly agree = 5. | ||

| PNs | Personal norms | |

| 1 | You will feel guilty about littering. | 0.501 |

| 2 | You will continue to sort waste even if the improvement to the village environment is not obvious. | 0.491 |

| 3 | You will continue to sort waste even if village does not give out free waste bags. | 0.389 |

| GI | Group identity | |

| 1 | You are very happy living in your village. | 0.474 |

| 2 | You are on good terms with your neighbors. | 0.445 |

| 3 | You have great trust in village cadres. | 0.368 |

| Variables | Model 1 (Logit) | Model 2 (Logit) | Model 3 (Logit) | Model 4 (OLS) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | S.E. | Coef. | S.E. | Coef. | S.E. | Coef. | S.E. | |

| SN1 | 0.321 *** | 0.127 | 0.331 *** | 0.126 | 0.335 *** | 0.131 | 0.134 *** | 0.050 |

| SN2 | 0.321 *** | 0.216 | 0.278 *** | 0.104 | 0.237 *** | 0.105 | 0.090 *** | 0.043 |

| PNs | — | — | 0.284 *** | 0.129 | 0.287 *** | 0.133 | 0.116 *** | 0.054 |

| GI | — | — | 0.040 | 0.125 | −0.076 | 0.134 | −0.038 | 0.057 |

| Gender | — | — | — | — | −0.226 * | 0.245 | −0.090 * | 0.096 |

| Age | — | — | — | — | −0.281 *** | 0.119 | −0.112 *** | −0.112 |

| Marital status | — | — | — | — | −1.095 *** | 0.500 | −0.437 *** | −0.437 |

| Party membership | — | — | — | — | 0.924 *** | 0.287 | 0.365 *** | 0.112 |

| Education | — | — | — | — | −0.135 * | 0.146 | −0.050 * | 0.055 |

| Gross annual income | — | — | — | — | 0.105 * | 0.087 | 0.040 * | 0.034 |

| Log Likelihood | −299.389 | −296.480 | −285.992 | — | ||||

| LR (P > chi2) | 18.940 (0.000) | 24.310 (0.000) | 45.290 (0.000) | — | ||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.030 | 0.039 | 0.073 | — | ||||

| F (P > F) | — | — | 7.330 (0.000) | 5.850 (0.000) | ||||

| Observation | 262 | |||||||

| Variables | Sorting Level = 0 | Sorting Level = 1 | Sorting Level = 2 | Sorting Level = 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SN1 | −0.023 *** (0.098) | −0.050 *** (0.193) | 0.039 *** (0.153) | 0.033 *** (0.134) |

| SN2 | −0.016 *** (0.077) | −0.035 *** (0.155) | 0.028 *** (0.122) | 0.024 *** (0.108) |

| PNs | −0.020 *** (0.098) | −0.043 *** (0.196) | 0.033 *** (0.156) | 0.029 *** (0.135) |

| GI | 0.005 (0.092) | 0.011 (0.200) | −0.009 (0.157) | −0.008 (0.135) |

| Gender | 0.015 * (0.169) | 0.034 * (0.363) | −0.026 * (0.285) | −0.023 * (0.246) |

| Age | 0.019 *** (0.088) | 0.042 *** (0.174) | −0.033 *** (0.138) | −0.028 *** (0.122) |

| Marital status | 0.074 *** (0.367) | 0.163 *** (0.733) | −0.128 *** (0.582) | −0.109 *** (0.509) |

| Party membership | −0.063 *** (0.229) | −0.137 *** (0.410) | 0.108 *** (0.331) | 0.092 *** (0.298) |

| Education | 0.009 * (0.101) | 0.020 * (0.216) | −0.016 * (0.170) | −0.013 * (0.146) |

| Gross annual income | −0.007 * (0.006) | −0.016 * (0.129) | 0.012 * (0.102) | 0.010 * (0.088) |

| Variables | Model 5 (All the Samples) | Model 6 (Low PN) | Model 7 (High PN) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | S.E. | Coef. | S.E. | Coef. | S.E. | |

| SN1 | 0.330 *** | 0.131 | 0.164 * | 0.192 | 0.601 *** | 0.205 |

| SN2 | 0.234 *** | 0.105 | 0.148 | 0.330 | 0.278 ** | 0.278 |

| PNs | 0.267 *** | 0.128 | — | — | — | — |

| Control variables | Controlled | |||||

| Log Likelihood | −286.151 | −149.264 | −129.908 | |||

| LR (P > chi2) | 44.790 (0.000) | 14.400 (0.109) | 33.600 (0.000) | |||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.073 | 0.046 | 0.115 | |||

| Observation | 262 | 139 | 123 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, Y.; Xu, M.; Chen, H. What Factors Affect Farmers’ Levels of Domestic Waste Sorting Behavior? A Case Study from Shaanxi Province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12141. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912141

Yuan Y, Xu M, Chen H. What Factors Affect Farmers’ Levels of Domestic Waste Sorting Behavior? A Case Study from Shaanxi Province, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12141. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912141

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Yalin, Minyue Xu, and Hanxin Chen. 2022. "What Factors Affect Farmers’ Levels of Domestic Waste Sorting Behavior? A Case Study from Shaanxi Province, China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12141. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912141