Assessing the Testability of the Multi-Theory Model (MTM) in Predicting Vaping Quitting Behavior among Young Adults in the United States: A Cross-Sectional Survey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection and Sampling

2.3. Ethical Considerations

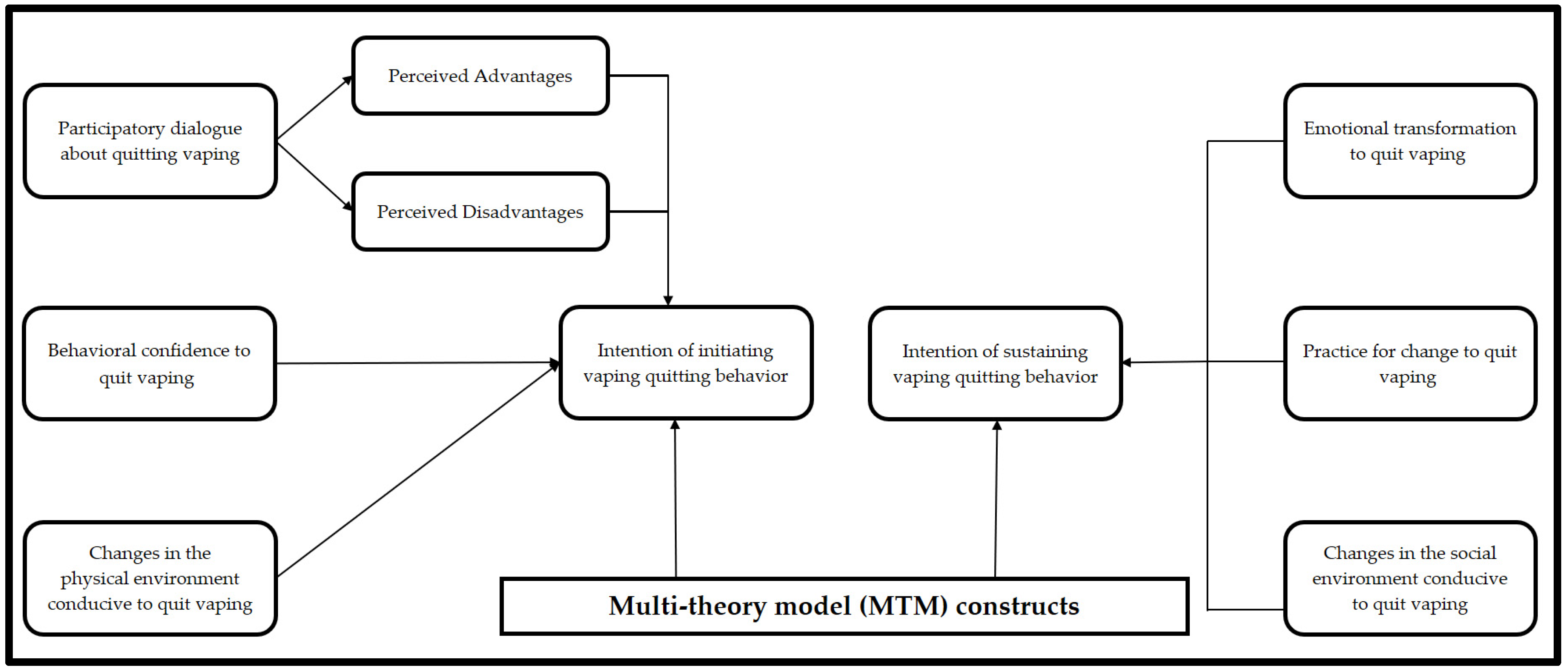

2.4. Survey Instrument

2.5. Face and Content Validity of the Survey Instrument

2.6. Sample Justification

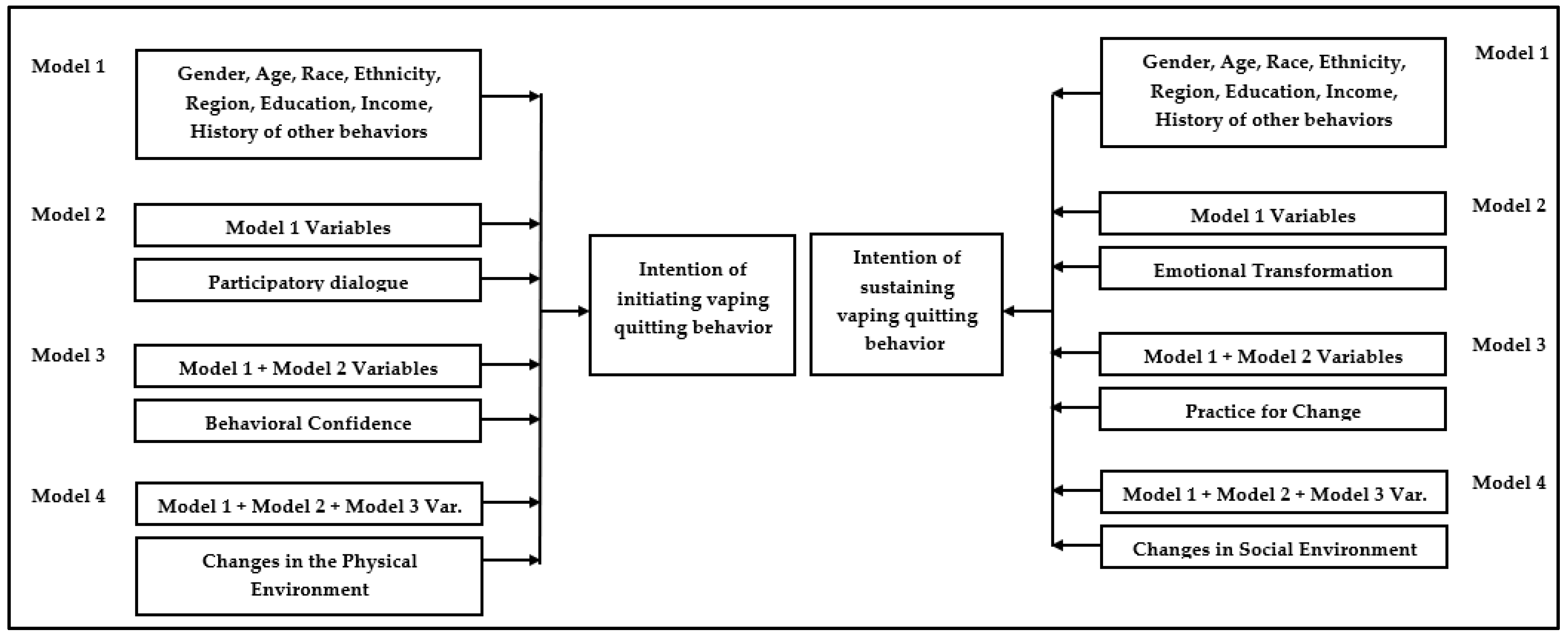

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Structural Model Assessment

3.1.1. Initiation

3.1.2. Sustenance

3.2. Reliability Diagnostics

3.3. Demographic and Behavioral Characteristics

3.4. Mean Values of MTM Constructs

3.5. Intercorrelation Matrix

3.6. Hierarchical Multiple Regression

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice

4.2. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Civiletto, C.W.; Hutchison, J. Electronic vaping delivery of Cannabis and Nicotine. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, S.J.; Erkinnen, M.; Lindgren, B.; Hatsukami, D. Beliefs about E-cigarettes: A focus group study with college students. Am. J. Health Behav. 2019, 43, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, C.; Mastrolonardo, E.; Frasso, R. Where there’s smoke, there’s fire: What current and future providers do and do not know about electronic cigarettes. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, S.; Kaufman, P.; Pelletier, H.; Baskerville, B.; Feng, P.; O’Connor, S.; Schwartz, R.; Chaiton, M. Is vaping cessation like smoking cessation? A qualitative study exploring the responses of youth and young adults who vape e-cigarettes. Addict. Behav. 2021, 113, 106687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struik, L.; Yang, Y. e-Cigarette Cessation: Content analysis of a quit vaping community on Reddit. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e28303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Electronic Cigarette Use among U.S. Adults. 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db365.htm\ (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Dai, H.; Leventhal, A.M. Prevalence of e-Cigarette use among adults in the United States, 2014-2018. JAMA 2019, 322, 1824–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pignataro, R.M.; Daramola, C. Becoming a tobacco-free campus: A survey of student attitudes, opinions and behaviors. Tob. Prev. Cessat. 2020, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Results from the Annual National Youth Tobacco Survey. 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/youth-and-tobacco/results-annual-national-youth-tobacco-survey (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Dai, H.; Siahpush, M. Use of E-Cigarettes for Nicotine, Marijuana, and Just Flavoring among U.S. Youth. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 58, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College Health Association. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Undergraduate Student Reference Group Data Report Fall 2018; American College Health Association: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-II_Fall_2018_Undergraduate_Reference_Group_Data_Report.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Abadi, S.; Couch, E.T.; Chaffee, B.W.; Walsh, M.M. Perceptions related to use of electronic cigarettes among California college Students. J. Dent. Hyg. 2017, 91, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dobbs, P.D.; Hodges, E.J.; Dunlap, C.M.; Cheney, M.K. Addiction vs. dependence: A mixed methods analysis of young adult JUUL users. Addict. Behav. 2020, 107, 106402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ickes, M.; Hester, J.W.; Wiggins, A.T.; Rayens, M.K.; Hahn, E.J.; Kavuluru, R. Prevalence and reasons for JUUL use among college students. J. Am. Coll. Health. 2020, 68, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallone, D.M.; Cuccia, A.F.; Briggs, J.; Xiao, H.; Schillo, B.A.; Hair, E.C. Electronic cigarette and JUUL use among adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 277–286, Correction in JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, (HHS Publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54). 2019. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Dinardo, P.; Rome, E.S. Vaping: The new wave of nicotine addiction. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2019, 86, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Ossip, D.J.; Rahman, I.; O’Connor, R.J.; Li, D. Electronic cigarette use and subjective cognitive complaints in adults. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagoner, K.G.; King, J.L.; Alexander, A.; Tripp, H.L.; Sutfin, E.L. Adolescent use and perceptions of JUUL and other Pod-style e-Cigarettes: A qualitative study to inform prevention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, J.W.; Wiggins, A.T.; Ickes, M.J. Examining intention to quit using Juul among emerging adults. J. Am. Coll. Health, 2021; 1–10, Published online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.T.; Hart, J.L.; Groom, A.; Landry, R.L.; Walker, K.L.; Giachello, A.L.; Tompkins, L.; Ma, J.Z.; Kesh, A.; Robertson, R.M.; et al. Age differences in electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) usage motivations and behaviors, perceived health benefit, and intention to quit. Addict. Behav. 2019, 98, 106054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antin, T.M.J.; Hunt, G.; Kaner, E.; Lipperman-Kreda, S. Youth perspectives on concurrent smoking and vaping: Implications for tobacco control. Int. J. Drug Policy 2019, 66, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.S.; Bottcher, M.M.; Cha, S.; Jacobs, M.A.; Pearson, J.L.; Graham, A.L. “It’s really addictive and I’m trapped”: A qualitative analysis of the reasons for quitting vaping among treatment-seeking young people. Addict. Behav. 2021, 112, 106599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadi, N.; Hadland, S.E.; Harris, S.K. Understanding the implications of the “vaping epidemic” among adolescents and young adults: A call for action. Subst. Abus. 2019, 40, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Anyimukwu, C.; Kim, R.W.; Nahar, V.K.; Ford, M.A. Predictors of responsible drinking or abstinence among college students who binge drink: A multitheory model approach. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2018, 118, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, M.; Batra, K.; Davis, R.E.; Wilkerson, A.H. Explaining handwashing behavior in a sample of college students during COVID-19 pandemic using the Multi-Theory Model (MTM) of health behavior change: A single institutional cross-sectional survey. Healthcare 2021, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Davis, R.E.; Wilkerson, A.H. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among college Students: A theory-based analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Petosa, R.L. Measurement and Evaluation for Health Educators; Jones and Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M.; Khubchandani, J.; Nahar, V.K. Applying a new theory to smoking cessation: Case of multi-theory model (MTM) for health behavior change. Health Promot. Perspect. 2017, 7, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Largo-Wight, E.; Kanekar, A.; Kusumoto, H.; Hooper, S.; Nahar, V.K. Using the Multi-Theory Model (MTM) of health behavior change to explain intentional outdoor nature contact behavior among college students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Stephens, P.M.; Nahar, V.K.; Catalano, H.P.; Lingam, V.C.; Ford, M.A. Using a Multitheory Model to predict initiation and sustenance of fruit and vegetable consumption among college students. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2018, 118, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkerson, A.H.; Davis, R.E.; Sharma, M.; Harmon, M.B.; McCowan, H.K.; Mockbee, C.S.; Ford, M.A.; Nahar, V.K. Use of the multi-theory model (MTM) in explaining initiation and sustenance of indoor tanning cessation among college students. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2022; Published online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Batra, K.; Flatt, J. Testing the Multi-Theory Model (MTM) to predict the use of new technology for social connectedness in the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare 2021, 9, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.; Sharma, M.; Leggett, S.; Sung, J.H.; Bennett, R.L.; Azevedo, M. Efficacy testing of the SAVOR (Sisters Adding Fruits and Vegetables for Optimal Results) intervention among African American women: A randomized controlled trial. Health Promot. Perspect. 2020, 10, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, T.; Sharma, M.; Shahbazi, M.; Sung, J.H.; Bennett, R.; Reese-Smith, J. The evaluation of a fourth-generation multi-theory model (MTM) based intervention to initiate and sustain physical activity. Health Promot. Perspect. 2019, 9, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESOMAR. Data Protection Checklist. Available online: https://www.esomar.org/ (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Qualtrics Market Research Panel Survey. 2021. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/market-research/ (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- United States Census Bureau. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Sharma, M. Multi-theory model (MTM) for health behavior change. Webmed Cent. Behav. 2015, 6, WMC004982. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M. Theoretical Foundations of Health Education and Health Promotion, 4th ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Sudbury, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, E.J.; Harrington, K.M.; Clark, S.L.; Miller, M.W. Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 76, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, D.; Lee, T.; Maydeu-Olivares, A. Understanding the model size effect on SEM fit indices. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2019, 79, 310–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahar, V.; KWells, J.; EDavis, R.; CJohnson, E.; WJohnson, J.; Sharma, M. Factors associated with initiation and sustenance of stress management behaviors in veterinary students: Testing of Multi-Theory Model (MTM). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Batra, K. Substance use among college students during COVID-19 times: A negative coping mechanism of escapism. J. Alcohol. Drug Educ. 2021, 65, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M.; Kanekar, A.; Batra, K.; Hayes, T.; Lakhan, R. Introspective meditation before seeking pleasurable activities as a stress reduction tool among college students: A multi-theory model based pilot study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kann, L.; McManus, T.; Harris, W.A.; Shanklin, S.L.; Flint, K.H.; Queen, B.; Lowry, R.; Chyen, D.; Whittle, L.; Thornton, J.; et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance-United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2018, 67, 1–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Lotfipour, S. Nicotine Gateway Effects on adolescent substance use. West J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 20, 696–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristic | Census Distribution, Population Parameters (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | Male: 48%; Female: 52%; Non-binary: natural fallout |

| Race | White (~75%); Black/AA (~13%); Asian or Pacific Islander (~6%); American Indian/Alaskan Native/Other (~6%) |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic (~18%); Non-Hispanic (~82%) |

| Region | Northeast: 17%; Midwest: 21%; West: 24%; South: 38% |

| Variable | Categories | Descriptive Statistic | 95% CI (LCL, UCL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 322 (52.0) | 48.0, 56.0 |

| Male | 289 (46.7) | 42.7, 50.7 | |

| Other | 8 (1.3) | 0.6, 2.5 | |

| Age in years (M ± SD) | - | 21.74 ± 1.6 | 21.61, 21.87 |

| Race | American Indian or Alaska Native | 10 (1.7) | 0.8, 3.0 |

| Asian | 36 (6.0) | 4.2, 8.1 | |

| Black or African American | 81 (13.4) | 10.8, 16.4 | |

| White | 463 (76.5) | 72.9, 79.9 | |

| Others including the multiethnic origin | 15 (2.5) | 1.4, 4.1 | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 111 (17.9) | 15.0, 21.2 |

| Non–Hispanic | 508 (82.1) | 78.8, 85.0 | |

| Region | Midwest | 132 (21.3) | 18.2, 24.8 |

| Northeast | 107 (17.3) | 14.4, 20.5 | |

| South | 238 (38.4) | 34.6, 42.4 | |

| West | 142 (22.9) | 19.7, 26.5 | |

| Education | College Degree (Associate or Bachelors) | 133 (21.4) | 18.3, 24.9 |

| Graduate Degree | 27 (4.4) | 2.9, 6.3 | |

| High school graduate (or equivalent including GED) | 229 (37.0) | 33.2, 40.9 | |

| Some college but no degree | 201 (32.5) | 28.8, 36.3 | |

| Other | 29 (4.7) | 3.2, 6.7 | |

| Employed | Yes | 402 (64.9) | 61.0, 68.7 |

| No | 217 (35.1) | 31.3, 39.0 | |

| * Hours worked (Per week) (M ± SD) | - | 32.41 ± 11.5 | 31.18, 33.64 |

| Income | Less than $ 50,000 | 315 (50.9) | 46.9, 54.9 |

| $ 50,000 to $ 100,000 | 225 (36.3) | 32.6, 40.3 | |

| $100,001 to $150,000 | 52 (8.4) | 6.3, 10.9 | |

| $150,001 to $200,000 | 18 (2.9) | 1.7, 4.6 | |

| More than $200,000 | 9 (1.5) | 0.7, 2.7 |

| Variable | Categories | Frequencies (Percentages) | 95% CI (LCL, UCL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vape Type | Cannabis | 206 (33.3) | 29.6, 37.1 |

| Nicotine | 384 (62.0) | 58.1, 65.9 | |

| Other | 29 (4.7) | 3.2, 6.7 | |

| Do you smoke cigarettes | Yes | 276 (44.6) | 40.6, 48.6 |

| No | 343 (55.4) | 51.4, 59.4 | |

| Do you drink alcohol | Yes | 510 (82.4) | 79.2, 85.2 |

| No | 109 (17.6) | 14.8, 20.8 | |

| How many of your closest friends vape | One or more | 570 (92.1) | 89.7, 94.1 |

| None | 49 (7.9) | 5.9, 10.3 | |

| Family members who vape | Yes | 326 (52.7) | 48.6, 56.7 |

| No | 293 (47.3) | 43.3, 51.4 | |

| Suffered from any mental health outcome as a result of vaping | Yes | 221 (35.8) | 32.0, 39.7 |

| No | 397 (64.2) | 60.3, 68.0 | |

| Suffered from any physical health outcome as a result of vaping | Yes | 265 (42.8) | 38.9, 46.8 |

| No | 354 (57.2) | 53.2, 61.1 |

| Variables | Possible range (Min, Max) | Range (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intent of Initiation | (0, 4) | (0, 4) | 1.89 ± 1.32 | 0.112 | −1.058 |

| 1. Perceived advantages | (0, 20) | (0, 20) | 11.43 ± 4.83 | −0.089 | −0.702 |

| 2. Perceived disadvantages | (0, 20) | (0, 20) | 7.50 ± 4.52 | 0.239 | −0.556 |

| 3. Behavioral Confidence | (0, 20) | (0, 20) | 8.84 ± 6.02 | 0.176 | −0.835 |

| 4. Changes in the Physical Environment | (0, 20) | (0, 20) | 10.09 ± 5.56 | 0.045 | −0.668 |

| Intent of Sustenance | (0, 4) | (0, 4) | 1.74 ± 1.35 | 0.184 | −1.086 |

| 5. Emotional Transformation | (0, 12) | (0, 12) | 5.98 ± 3.55 | 0.043 | −0.726 |

| 6. Practice for Change | (0, 12) | (0, 12) | 5.77 ± 3.43 | 0.088 | −0.715 |

| 7. Changes in the Social Environment | (0, 12) | (0, 12) | 6.05 ± 3.40 | −0.046 | −0.637 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Participatory Dialogue | 1 | 0.25 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.25 ** |

| 2. Behavioral Confidence | 0.25 ** | 1 | 0.77 ** | 0.74 ** | 0.72 ** | 0.50 ** |

| 3. Changes in the Physical Environment | 0.29 ** | 0.77 ** | 1 | 0.80 ** | 0.76 ** | 0.59 ** |

| 4. Emotional Transformation | 0.32 ** | 0.74 ** | 0.80 ** | 1 | 0.79 ** | 0.55 ** |

| 5. Practice for Change | 0.27 ** | 0.72 ** | 0.76 ** | 0.79 ** | 1 | 0.60 ** |

| 6. Changes in the Social Environment | 0.25 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.59 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.60 ** | 1 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | B | β | B | β | B | β | |

| Constant | 3.241 ** | - | 2.542 * | - | 1.275 | - | 0.888 | - |

| Age | −0.023 | −0.028 | −0.019 | −0.024 | −0.017 | −0.020 | −0.012 | −0.014 |

| Gender: Male (Ref: Female) | 0.096 | 0.036 | 0.071 | 0.027 | 0.055 | 0.021 | 0.013 | 0.005 |

| Other gender (Ref: Female) | −0.996 * | −0.085 | −0.740 | −0.063 | −0.695 | −0.059 | −0.630 | −0.054 |

| Race: Non-White (Ref: White) | 0.103 | 0.034 | 0.143 | 0.047 | −0.018 | −0.006 | 0.008 | 0.003 |

| Ethnicity: Non-Hispanic (Ref: Hispanic) | −0.280 | −0.081 | −0.141 | −0.041 | −0.062 | −0.018 | −0.042 | −0.012 |

| Region: Northeast (Ref: Midwest) | 0.059 | 0.017 | 0.062 | 0.018 | 0.051 | 0.015 | 0.052 | 0.015 |

| South | 0.177 | 0.065 | 0.134 | 0.049 | 0.165 | 0.061 | 0.196 | 0.072 |

| West | 0.060 | 0.019 | 0.071 | 0.023 | 0.145 | 0.046 | 0.156 | 0.049 |

| Education (Ref: Associate or Bachelors) | ||||||||

| Graduate Degree | 0.166 | 0.026 | 0.177 | 0.027 | 0.078 | 0.012 | 0.133 | 0.021 |

| High school graduate or equivalent | −0.127 | −0.046 | −0.044 | −0.016 | −0.019 | −0.007 | −0.057 | −0.021 |

| Some college but no degree | −0.164 | −0.058 | −0.099 | −0.035 | −0.129 | −0.046 | −0.202 | −0.072 |

| Other | 0.085 | 0.014 | 0.209 | 0.033 | 0.041 | 0.007 | −0.014 | −0.002 |

| Income: $ 50,000 to $ 100,000 (Ref: <$50,000) | −0.017 | −0.006 | −0.022 | −0.008 | 0.003 | 0.001 | −0.017 | −0.006 |

| $100,001 to $150,000 | 0.102 | 0.021 | 0.129 | 0.027 | −0.036 | −0.007 | −0.023 | −0.005 |

| $150,001 to $200,000 | 0.060 | 0.008 | 0.128 | 0.016 | −0.262 | −0.033 | −0.347 | −0.044 |

| More than $200,000 | −0.020 | −0.002 | −0.168 | −0.015 | −0.399 | −0.036 | −0.392 | −0.035 |

| Cigarette smoking (Ref: No) | −0.099 | −0.037 | −0.020 | −0.008 | 0.088 | 0.033 | 0.087 | 0.033 |

| Alcohol consumption (Ref: No) | −0.20 | −0.058 | −0.182 | −0.052 | −0.247 * | −0.071 | −0.214 | −0.062 |

| Vaping among friends (Ref: No) | −0.417 * | −0.085 | −0.30 | −0.061 | −0.097 | −0.020 | −0.089 | −0.018 |

| Vaping among family (Ref: No) | −0.195 | −0.074 | −0.083 | −0.032 | −0.013 | −0.005 | 0.018 | 0.007 |

| Participatory dialogue | - | - | 0.064 ** | 0.290 | 0.036 ** | 0.163 | 0.03 ** | 0.136 |

| Behavioral confidence | - | - | - | - | 0.123 ** | 0.560 | 0.076 ** | 0.345 |

| Changes in the physical environment | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.069 ** | 0.291 |

| R2 | 0.050 | - | 0.127 | - | 0.406 | - | 0.439 | - |

| F | 1.568 | - | 4.120 ** | - | 18.514 ** | - | 20.215 ** | - |

| Δ R2 | 0.050 | - | 0.077 | - | 0.279 | - | 0.033 | - |

| Δ F | 1.568 | - | 52.455 ** | - | 280.310 ** | - | 34.646 ** | - |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | B | β | B | β | B | β | |

| Constant | 2.113 * | - | 0.878 | - | 0.339 | - | 0.029 | - |

| Age | 4 | 0.011 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.013 | 0.015 | 0.018 | 0.022 |

| Gender: Male (Ref: Female) | 0.12 | 0.045 | 0.103 | 0.038 | 0.095 | 0.035 | 0.1 | 0.037 |

| Other gender (Ref: Female) | −0.516 | −0.043 | −0.121 | −0.01 | −0.083 | −0.007 | −0.236 | −0.02 |

| Race: Non-White (Ref: White) | 0.112 | 0.036 | 0.017 | 0.005 | −0.043 | −0.014 | −0.03 | −0.01 |

| Ethnicity: Non-Hispanic (Ref: Hispanic) | −0.331 * | −0.094 | −0.228 | −0.065 | −0.197 | −0.056 | −0.163 | −0.046 |

| Region: Northeast (Ref: Midwest) | 0.175 | 0.049 | 0.179 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.062 | 0.182 | 0.051 |

| South | 0.273 | 0.098 | 0.229 | 0.083 | 0.237 | 0.085 | 0.225 | 0.081 |

| West | 0.225 | 0.07 | 0.229 | 0.071 | 0.261 | 0.081 | 0.228 | 0.071 |

| Education (Ref: Associate or Bachelor’s) | ||||||||

| Graduate Degree | 0.135 | 0.02 | −0.085 | −0.013 | −0.006 | −0.001 | 0.063 | 0.009 |

| High school graduate or equivalent | −0.155 | −0.056 | −0.224 | −0.08 | −0.149 | −0.053 | −0.116 | −0.042 |

| Some college but no degree | −0.331 * | −0.115 | −0.376 * | −0.131 | −0.269 * | −0.094 | −0.29 * | −0.101 |

| Other | −0.069 | −0.011 | −0.181 | −0.028 | −0.091 | −0.014 | −0.085 | −0.013 |

| Income: $ 50,000 to $ 100,000 (Ref: <$50,000) | 0.031 | 0.011 | 0.033 | 0.012 | 0.015 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.004 |

| $100,001 to $150,000 | 0.039 | 0.008 | −0.034 | −0.007 | −0.055 | −0.011 | −0.02 | −0.004 |

| $150,001 to $200,000 | −0.112 | −0.014 | −0.345 | −0.043 | −0.443 | −0.055 | −0.44 | −0.055 |

| More than $200,000 | −0.065 | −0.006 | −0.245 | −0.022 | −0.126 | −0.011 | −0.212 | −0.019 |

| Cigarette smoking (Ref: No) | −0.163 | −0.06 | −0.091 | −0.034 | −0.116 | −0.043 | −0.1 | −0.037 |

| Alcohol consumption (Ref: No) | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.02 | 0.006 | 0.073 | 0.021 | 0.056 | 0.016 |

| Vaping among friends (Ref: No) | −0.309 | −0.062 | −0.266 | −0.053 | −0.187 | −0.037 | −0.218 | −0.044 |

| Vaping among family (Ref: No) | −0.114 | −0.042 | 0.017 | 0.006 | 0.026 | 0.01 | 0.048 | 0.018 |

| Emotional transformation | - | - | 0.195 ** | 0.512 | 0.069 * | 0.181 | 0.054 * | 0.141 |

| Practice for change | - | - | - | 0.167 ** | 0.425 | 0.131 ** | 0.332 | |

| Changes in the social environment | - | - | - | - | 0.082 ** | 0.206 | ||

| R2 | 0.045 | - | 0.298 | - | 0.364 | - | 0.390 | - |

| F | 1.416 | - | 12.082 ** | - | 15.531 ** | - | 16.533 ** | - |

| Δ R2 | 0.045 | - | 0.253 | - | 0.066 | - | 0.026 | - |

| Δ F | 1.416 | - | 215.257 ** | - | 62.013 ** | - | 24.889 ** | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharma, M.; Batra, K.; Batra, R.; Dai, C.-L.; Hayes, T.; Ickes, M.J.; Singh, T.P. Assessing the Testability of the Multi-Theory Model (MTM) in Predicting Vaping Quitting Behavior among Young Adults in the United States: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912139

Sharma M, Batra K, Batra R, Dai C-L, Hayes T, Ickes MJ, Singh TP. Assessing the Testability of the Multi-Theory Model (MTM) in Predicting Vaping Quitting Behavior among Young Adults in the United States: A Cross-Sectional Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912139

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Manoj, Kavita Batra, Ravi Batra, Chia-Liang Dai, Traci Hayes, Melinda J. Ickes, and Tejinder Pal Singh. 2022. "Assessing the Testability of the Multi-Theory Model (MTM) in Predicting Vaping Quitting Behavior among Young Adults in the United States: A Cross-Sectional Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912139

APA StyleSharma, M., Batra, K., Batra, R., Dai, C.-L., Hayes, T., Ickes, M. J., & Singh, T. P. (2022). Assessing the Testability of the Multi-Theory Model (MTM) in Predicting Vaping Quitting Behavior among Young Adults in the United States: A Cross-Sectional Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912139