The Feasibility and Acceptability of an Online CPD Programme to Enhance PE Teachers’ Knowledge of Muscular Fitness Activity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. CPD Conceptualisation

2.2. CPD Development

2.2.1. Meeting One

2.2.2. Meeting Two

2.2.3. Meeting Three

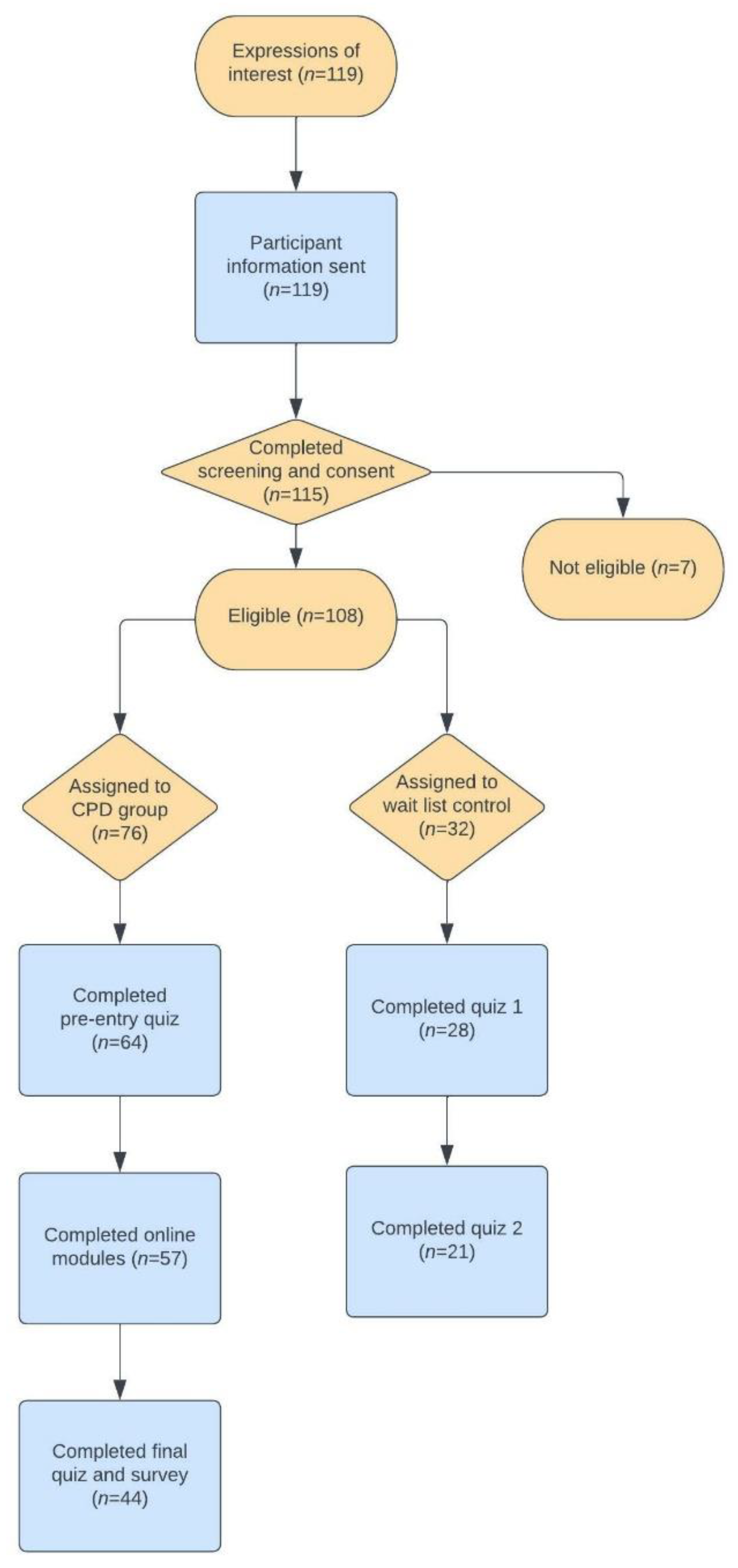

2.3. CPD Participant Recruitment and Distribution

2.4. Analysis of CPD Data

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.2. Qualitative Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Knowledge and Confidence

“This has really opened my eyes, not sure why this isn’t discussed more. I took a lot away from this and get now why strength is just as important for health as cardio fitness”.[Female, North West England, Over 15 years experience]

“The athletic models were useful and something we can use for our lessons. They will feature in our GCSE class next year to help pupils understand periodisation and we can use them to plan our lesson progressions”.[Male, London, 5–14 years experience]

4.2. Practical Application

“I already knew about plyometric exercise through my UKA (UK Athletics) course. The CPD helped take what I know and put it into a gym lesson. It makes sense to use the plyometric progression model and help pupils work towards their own plan and fitness, something they can even use for GCSE work. Thank you”.[Male, North East England, over 15 years experience]

“Who else is doing this (MF activity)? It would be good to see how others have used it (MF activity) in their PE lessons”.[Female, East of England, under 5 years experience]

4.3. Support and Resources

“Going at my own pace in my own time was great. I could work it around work and home life. I have struggled with workshops in the past, especially with having issues around my learning ability. I have to go over things and take my time”.[Female, Yorkshire and the Humber, 5–14 years experience]

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davies, D.S.C.; Atherton, F.; McBride, M.; Calderwood, C. UK Chief Medical Officers’ Physical Activity Guidelines; Department of Health and Social Care: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–582. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.J.; Eather, N.; Morgan, P.J.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; Lubans, D.R. The health benefits of muscular fitness for children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 1209–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Hermoso, A.; Ramírez-Campillo, R.; Izquierdo, M. Is Muscular Fitness Associated with Future Health Benefits in Children and Adolescents? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 1079–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Gómez, D.; Welk, G.J.; Puertollano, M.A.; Del-Campo, J.; Moya, J.M.; Marcos, A.; Veiga, O.L. Associations of physical activity with muscular fitness in adolescents. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2011, 21, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.J.; Eather, N.; Weaver, R.G.; Riley, N.; Beets, M.W.; Lubans, D.R. Behavioral Correlates of Muscular Fitness in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faigenbaum, A.D.; Lloyd, R.S.; MacDonald, J.; Myer, G.D. Citius, Altius, Fortius: Beneficial effects of resistance training for young athletes: Narrative review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faigenbaum, A.D.; Rebullido, T.R.; Peña, J.; Chulvi-Medrano, I. Resistance Exercise for the Prevention and Treatment of Pediatric Dynapenia. J. Sci. Sport Exerc. 2019, 1, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Comprehensive School Physical Activity Programs; Human Kinetics Library: Champaign, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, R.; Adams, J.; van Sluijs, E.M.F. Are school-based physical activity interventions effective and equitable? A meta-analysis of cluster randomized controlled trials with accelerometer-assessed activity. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, A.; Fairclough, S.J.; Kosteli, M.C.; Noonan, R.J. Efficacy of School-Based Interventions for Improving Muscular Fitness Outcomes in Adolescent Boys: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faigenbaum, A.D.; McFarland, J.E. Resistance training for kids: Right from the Start. ACSMs Health Fit. J. 2016, 20, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichardo, A.W.; Oliver, J.L.; Harrison, C.B.; Maulder, P.S.; Lloyd, R.S. Integrating resistance training into high school curriculum. Strength Cond. J. 2019, 41, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.S.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; Stone, M.H.; Oliver, J.L.; Jeffreys, I.; Moody, J.A.; Brewer, C.; Pierce, K.C.; McCambridge, T.M.; Howard, R.; et al. Position statement on youth resistance training: The 2014 International Consensus. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, D.D.; Voss, C.; Sandercock, G.R.H. Fitness testing for children: Let’s mount the zebra! J. Phys. Act. Health 2015, 12, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Hoor, G.A.; Plasqui, G.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Rutten, G.M.; Schols, A.M.W.J.; Kok, G. A new direction in psychology and health: Resistance exercise training for obese children and adolescents. Psychol. Health 2016, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, S.G.; Smith, J.J.; Estabrooks, P.A.; Nathan, N.; Noetel, M.; Morgan, P.J.; Salmon, J.; Dos Santos, G.C.; Lubans, D.R. Evaluating the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance of the Resistance Training for Teens program. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, P.J.; Nettlefold, L.; Race, D.; Hoy, C.; Ashe, M.C.; Wharf Higgins, J.; McKay, H.A. Implementation of school based physical activity interventions: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2015, 72, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, N.; Elton, B.; Babic, M.; McCarthy, N.; Sutherland, R.; Presseau, J.; Seward, K.; Hodder, R.; Booth, D.; Yoong, S.L.; et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of physical activity policies in schools: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2018, 107, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGladrey, B.W.; Hannon, J.C.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; Shultz, B.B.; Shaw, J.M. High school physical educators’ and sport coaches’ knowledge of resistance training principles and methods. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.G.; Smith, J.J.; Hansen, V.; Lindhout, M.I.C.; Morgan, P.J.; Lubans, D.R. Implementing Resistance Training in Secondary Schools: An Exploration of Teachers’ Perceptions. Transl. J. Am. Coll. Sport. Med. 2018, 3, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, S.G.; Peralta, L.R.; Lubans, D.R.; Foweather, L.; Smith, J.J. Implementing a school-based physical activity program: Process evaluation and impact on teachers’ confidence, perceived barriers and self-perceptions. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2019, 24, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Haegele, J.A.; Foot, R. In-service physical educators’ experiences of online adapted physical education endorsement courses. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2017, 34, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantz-Andersson, A.; Lundin, M.; Selwyn, N. Twenty years of online teacher communities: A systematic review of formally-organized and informally-developed professional learning groups. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 75, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, N.; Lewis, S.; Nahavandi, D.; Amsbury, K.; Barnett, L.M. Teacher perspectives of online continuing professional development in physical education. Sport Educ. Soc. 2020, 27, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannehill, D.; Demirhan, G.; Čaplová, P.; Avsar, Z. Continuing professional development for physical education teachers in Europe. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2021, 27, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garet, M.S.; Porter, A.C.; Desimone, L.; Birman, B.F.; Yoon, K.S. What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2001, 38, 915–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordingley, R.; Higgins, P.; Greany, S.; Buckler, T.; Coles-Jordan, N.; Crisp, D.; Saunders, B.; Coe, L. ‘Standard for Teachers’ Professional Development: Implementation Guidance for School Leaders, Teachers, and Organisations that Offer Professional Development for Teachers’. 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/standard-for-teachers-professional-development (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- dos Santos Duarte Junior, M.A.; López-Gil, J.F.; Caporal, G.C.; Mello, J.B. Benefits, risks and possibilities of strength training in school Physical Education: A brief review. Sport Sci. Health 2022, 18, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, K.V.; Killian, C.M.; Burnett, R. Integrating Strength and Conditioning into a High School Physical Education Curriculum: A Case Example. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 2021, 92, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, L.M.; Jacquez, F. Participatory Research Methods—Choice Points in the Research Process. J. Particip. Res. Methods 2020, 1, 13244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Srivastav, G. Study and Review of Learning Management System Software. In Innovations in Computer Science and Engineering: Proceedings of 7th ICICSE; Saini, H.S., Sayal, R., Buyya, R., Aliseri, G., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 373–383. ISBN 9789811520433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Guo, Q.; Gierl, M.J. Multiple-choice item distractor development using topic modeling approaches. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bogdan, R.C.; Biklen, S.K. Qualitative Research Methods: An Introduction to Theories and Methods, 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McAlister, A.M.; Lee, D.M.; Ehlert, K.M.; Kajfez, R.L.; Faber, C.J.; Kennedy, M.S. Qualitative coding: An approach to assess inter-rater reliability. In Proceedings of the 2017 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Columbus, OH, USA, 25–28 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Joffe, H. Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 160940691989922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K.; Dowell, A.; Nie, J.B. Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data; A case study of codebook development. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.; Caddick, N. Qualitative methods in sport: A concise overview for guiding social scientific sport research. Asia Pac. J. Sport Soc. Sci. 2012, 1, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, K.; Jones, L. A systematic review of the factors—Enablers and barriers—Affecting e-learning in health sciences education. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainer, P.; Cropley, B.; Jarvis, S.; Griffiths, R. From policy to practice: The challenges of providing high quality physical education and school sport faced by head teachers within primary schools. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2012, 17, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.; Bourke, S. Non-specialist teachers’ confidence to teach PE: The nature and influence of personal school experiences in PE. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2008, 13, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, N.; Eather, N.; Morgan, P.J.; Salmon, J.; Barnett, L.M. Characteristics of Teacher Training in School-Based Physical Education Interventions to Improve Fundamental Movement Skills and/or Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, D.H. Strategies for Inclusion: A Handbook for Physical Educators. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2016, 20, 91–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichardo, A.W.; Oliver, J.L.; Harrison, C.B.; Maulder, P.S.; Lloyd, R.S. Integrating models of long-term athletic development to maximize the physical development of youth. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2018, 13, 1189–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.S.; Meyers, R.W.; Oliver, J.L. The Natural Development and Trainability of Plyometric Ability During Childhood the inclusion of plyometrics within youth-based strength and conditioning programs is becoming more popular as a means to develop stretch-shortening cycle ability. Plyometric 2011, 33, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Deyasi, A.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Debnath, P.; Sarkar, A. Authentic Pedagogy: A Project-Oriented Teaching–Learning Method Based on Critical Thinking. In Intelligent Systems Reference Library; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: London, UK, 2021; Volume 197, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, S.; Block, M.; Kelly, L. The Impact of Online Professional Development on Physical Educators‘ Knowledge and Implementation of Peer Tutoring. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2020, 67, 424–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armour, K.M.; Yelling, M.R. Continuing Professional Development for Experienced Physical Education Teachers: Towards Effective Provision. Sport Educ. Soc. 2004, 9, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K.; Meredith, C.; Packer, T.; Kyndt, E. Teacher communities as a context for professional development: A systematic review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 61, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Patton, K.; Gonçalves, L.; Luguetti, C.; Lee, O. Learning communities and physical education professional development: A scoping review. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2022, 28, 500–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, K.; Parker, M.; Tannehill, D. Helping Teachers Help Themselves: Professional Development That Makes a Difference. NASSP Bull. 2015, 99, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, X.; Liu, X.; Stephenson, R.; Guan, J.; Hodges, M. Student health-related fitness testing in school-based physical education: Strategies for student self-testing using technology. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2020, 26, 552–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, Z.; Alfrey, L.; Young, L. The Psychological Impact of Fitness Testing in Physical Education: A Pilot Experimental Study Among Australian Adolescents. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2021, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armour, K.; Makopoulou, K.; Chambers, F. Progression in physical education teachers’ career-long professional learning: Conceptual and practical concerns. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2012, 18, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, K.; Parker, M.; Neutzling, M.M. Tennis shoes required: The role of the facilitator in professional development. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2012, 83, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, S.; Cordingley, P.; Greany, T.; Coe, R. Developing Great Teaching: Lessons from the international reviews into effective professional development (summary). Educ. Next 2012, 01, 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Avalos, B. Teacher professional development in Teaching and Teacher Education over ten years. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2011, 27, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Module | Overview |

|---|---|

| Preliminary Stage | Welcome video, participant information, consent, and the entry knowledge quiz. |

| Introduction | Brief rationale, definitions of key terminology and a group introduction forum. |

| Physical Activity | Overview of PA guidelines, health benefits of MF, addressing common misconceptions surrounding MF activity and two discussion forums about MF. |

| Muscular Fitness Development | Implementation of MF in schools, programming and periodization, common misconceptions. |

| Plyometrics | Introduction to plyometrics, safety considerations, programming, plyometric progression model, plyometric discussion forum. |

| Delivery and Long-Term Development | Teacher conduct in delivering MF activity, delivery and class management considerations, physical development models, discussion forum on MF delivery. |

| Monitoring and Assessment | Assessing MF, overview of common MF assessment tools, conducting MF assessments, discussion forum for MF assessments. |

| Round Up | CPD round up, knowledge quiz, exit survey. |

| Characteristics | All (n = 65) | CPD Group (n = 44) | Wait List Control Group (n = 21) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex % (n) | |||

| Male | 55.4 (36) | 56.8 (25) | 52.4 (11) |

| Female | 44.6 (29) | 43.2 (19) | 47.6 (10) |

| School Location % (n) | |||

| Cymru Wales | 7.7 (5) | 9.1 (4) | 4.8 (1) |

| East of England | 7.7 (5) | 4.5 (2) | 14.3 (3) |

| North East and Cumbria | 3.1 (2) | - | 9.5 (2) |

| East Midlands | 13.8 (9) | 15.9 (7) | 9.5 (2) |

| London | 7.7 (5) | 9.1 (4) | 4.8 (1) |

| North West | 10.8 (7) | 11.4 (5) | 9.5 (2) |

| Northern Ireland | 3.1 (2) | 2.3 (1) | 4.8 (1) |

| Scotland | 6.2 (4) | 4.5 (2) | 9.5 (2) |

| South East | 15.4 (10) | 18.2 (8) | 9.5 (2) |

| South West | 7.7 (5) | 6.8 (3) | 9.5 (2) |

| West Midlands | 10.8 (7) | 11.4 (5) | 9.5 (2) |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 6.2 (4) | 6.8 (3) | 4.8 (1) |

| Teaching Experience (years) % (n) | |||

| <5 | 35.4 (23) | 36.4 (16) | 33.3 (7) |

| 5–14 | 33.8 (22) | 34.1 (15) | 33.3 (7) |

| >15 | 30.8 (20) | 29.5 (13) | 33.3 (7) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cox, A.; Noonan, R.J.; Fairclough, S.J. The Feasibility and Acceptability of an Online CPD Programme to Enhance PE Teachers’ Knowledge of Muscular Fitness Activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912132

Cox A, Noonan RJ, Fairclough SJ. The Feasibility and Acceptability of an Online CPD Programme to Enhance PE Teachers’ Knowledge of Muscular Fitness Activity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912132

Chicago/Turabian StyleCox, Ashley, Robert J. Noonan, and Stuart J. Fairclough. 2022. "The Feasibility and Acceptability of an Online CPD Programme to Enhance PE Teachers’ Knowledge of Muscular Fitness Activity" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912132

APA StyleCox, A., Noonan, R. J., & Fairclough, S. J. (2022). The Feasibility and Acceptability of an Online CPD Programme to Enhance PE Teachers’ Knowledge of Muscular Fitness Activity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912132