Experiences of Using Misoprostol in the Management of Incomplete Abortions: A Voice of Healthcare Workers in Central Malawi

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting

2.3. Study Participants

2.4. Data Collection and Management

2.5. Patient and Public Involvement Statement

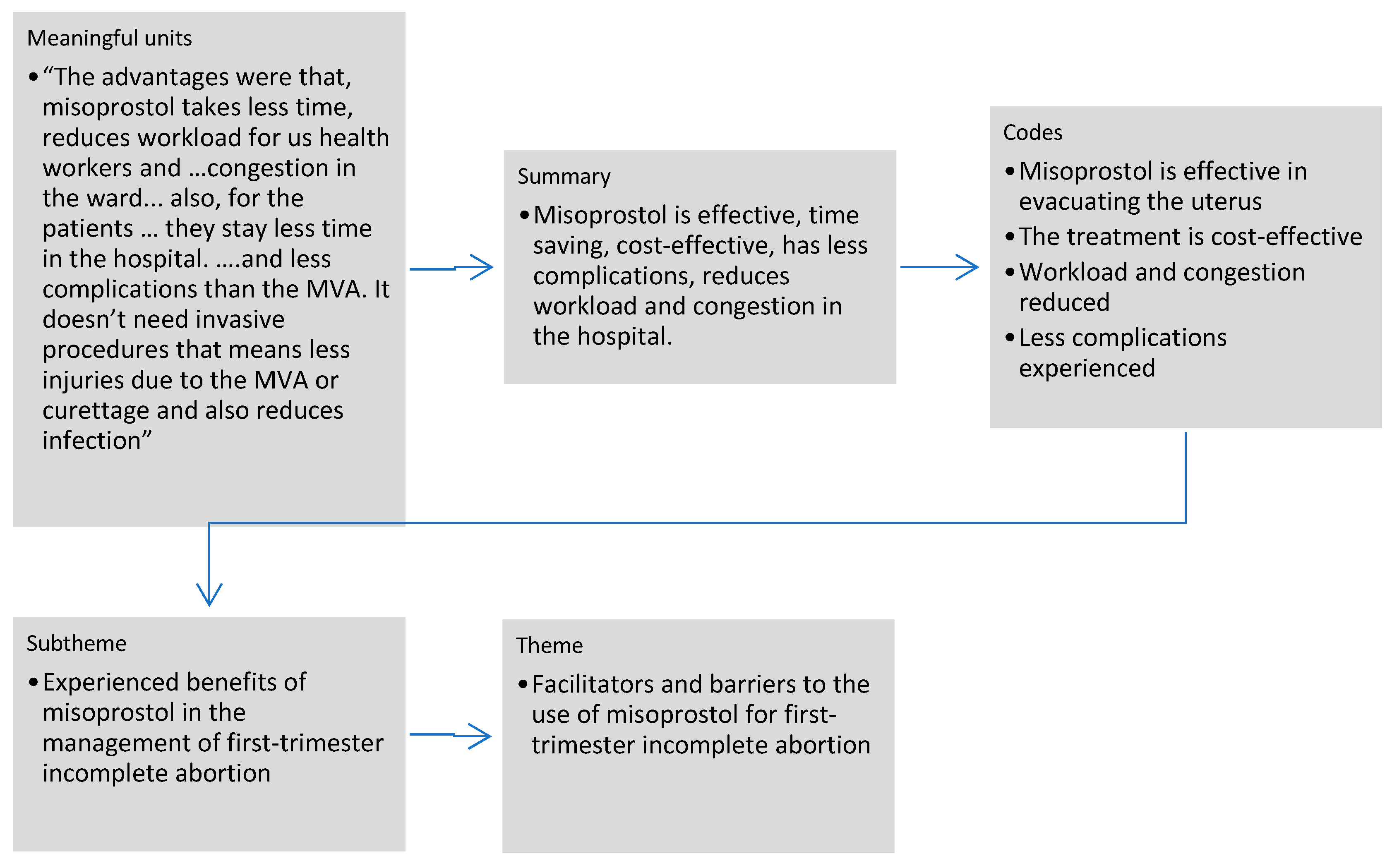

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Facilitators and Barriers to the Use of Misoprostol for First-Trimester Incomplete Abortion

3.2.1. Health Providers’ Knowledge of the Use of Misoprostol for First-Trimester Incomplete Abortion

“It was from school I did not go for the [in-service] training, and also … on job training, we get if from friends, those people who know the management, sometimes they can also post the management in the wards so we just read from there”.[res 1B]

“We may have knowledge on how to use misoprostol in the first-trimester, some just read articles but haven’t gone through a formal training. So, we need a lot of people to be trained. And also, as an institution not all of us will [always] be here, some will be coming [and] some will be going out so we have a lot of newcomers who don’t have knowledge on how to use it. As long as we are doing mentorship, but also trainings are much important”.[res 9 S]

3.2.2. Health Providers’ Confidence in the Use of Misoprostol

“I am also confident when am treating women who have undergone incomplete abortion because I have all the knowledge that is required to treat these women using medical management, and whenever I am stuck I also go back to my notes because I have a handout that you gave us last time, just to make sure that I am doing the right thing”.[res 1 M]

3.2.3. Experienced Benefits of Misoprostol in the Management of First-Trimester Incomplete Abortion

“I can say that the misoprostol was effective, because for the women who came… with the right information about the gestational age they were doing fine at the review day, no bleeding no whatever, during scanning everything is complete. But, for the less that were giving wrong information of gestational age …, they were coming again with bleeding and after scanning you find that there is still remains of products of conception and after further investigations you find out that they were giving wrong information on gestation age, maybe it was over three months but for the first-trimester [incomplete abortions] it was really effective”.[res 8 S]

“The advantages were that, … misoprostol takes less time, reduces workload for us health workers and also congestion in the ward were reduced. And also, for the patients themselves they stay less time in the hospital. Maybe for the MVA some of them would wait for two days before the MVA was done. But for this the same day they came after history taking, examination, and find out they are eligible for the medical management, they were given and go home and also less complications than the MVA. It doesn’t need invasive procedures that means less injuries due to the MVA or curettage and also reduces infection”.[res 8 S]

“Just to add it also provides privacy, … some people with abortion, for others to know they have gone through abortion is like they don’t feel comfortable, so with this misoprostol they can just be treated at OPD [outpatient department] and go home…And in addition, when giving misoprostol you just need to know how you are going to give the misoprostol unlike MVA whereby you have to go through training in order to provide the service, you can just even read the notes on how to give misoprostol you are good to go.…… Like in my case I was not trained, during that time I was on… COVID isolation, … but when I came back I read the notes and I am able to give it”.[res 8 M]

3.2.4. Availability and Accessibility of Misoprostol for First-Trimester Incomplete Abortion

“Since the introduction of this medical management of incomplete abortion using misoprostol, the demand now is very high so we don’t always have this drug because we encounter so many clients per day and also our pharmacy does not always have this drug, so sometimes we also experience this challenge of being out of stock”.[res 1 M]

3.2.5. Health Providers’ Satisfaction with the Use of Misoprostol in Post-Abortion Care

“Yes, we are very much satisfied with the use of misoprostol in managing incomplete abortion as we have already said it doesn’t require much time…..”.[res 3 S]

3.2.6. Supportive Supervision in the Use of Misoprostol

“We can say that supervision is not there … No, we assume that the person who is taking the drug knows how to use it, know how to handle it”.[res 5 S]

3.3. Care Provided to Women with First-Trimester Incomplete Abortion

3.3.1. An Encounter with a Patient: Treatment Offered

“…the patient may present with bleeding following… few months amenorrhea. … the patient is… tested for pregnancy…, submit urine… we… check if patient was really pregnant. …when the test comes… positive, we… proceed to… do… abdominal examination and assess gestational [age in] weeks. …if … gestation is… within… first-trimester, the woman [is] treated with…misoprostol… 600 mcg orally, and then we observe her… for… few hours in case she might have… complications like… bleeding if she has no… complication we… explain to her… that she might experience… back pain and some bleeding as the drug… clean… the uterus, we… explain… to the woman so that she should not wonder when it happens. …we advise her to report any danger signs like … signs of shock, if she bleeds excessively she has to report back. …we give her …one week …. for review, [to] see if the drug has been successful when she comes… we take history… about … her experience post drug. So, if… no… complications, we proceed… giving her the post-abortion family planning … of her choice…”.[res 2 M]

3.3.2. Preferred Treatment by Healthcare Workers

“I will prefer using misoprostol since it will not require much time like it will take doing the MVA because you need to prepare the patient and all the equipment you assemble … with misoprostol you just take the medication and give the client and she can go home right away”.[res 3 S]

3.3.3. Experiences of Follow-Up Care of Patients Treated with Misoprostol

“To be honest I think those who come are those who have problems because when we treat these women if they are well they don’t come back, but if they feel like something else is not working on them, they come back maybe even [before] the day you have given them. So, we can say that during follow-up not more are coming…”.[res 2 B]

3.3.4. Complications

“Like for me, I have never seen a woman who has experienced a major complication following the treatment …using misoprostol. They only complain about pain, … others … complain about bleeding of which we already expect … so as for me I have never seen any major complication”.[res 1 M]

3.3.5. Type of Healthcare Workers Providing Medical Management

“The challenge is that we [are] … not really practicing it. Most [of the] time we depend upon clinicians [physicians] to order and give the drug. But we know how to give it and manage the patient… We give but under clinician’s prescription because when documenting always the pharmacy people wants the name of the clinician who prescribes”.[res 6 S]

3.3.6. Task Shifting

“Yah there is task shifting because nurses as well… can handle these patients. During some weekends maybe, some clinicians might not be available, the nurses can do this management”.[res 2 M]

4. Discussion

Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- NSO (Malawi). Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2015-16; NSO and ICF: Zomba, Malawi; Rockville, MD, USA, 2017.

- Miller, C. Maternal Mortality from Induced Abortion in Malawi: What Does the Latest Evidence Suggest? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankole, A.; Remez, L.; Owolabi, O.; Philbin, J.; Williams, P. From Unsafe to Safe Abortion in Sub-Saharan Africa: Slow but Steady Progress; Guttmacher Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Malawi Government. Report of the Law Commission on the Review of the Law on Abortion; Government Printer: Lilongwe, MD, USA, 2016.

- Polis, C.B.; Mhango, C.; Philbin, J.; Chimwaza, W.; Chipeta, E.; Msusa, A. Incidence of induced abortion in Malawi, 2015. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalilani-Phiri, L.; Gebreselassie, H.; Levandowski, B.A.; Kuchingale, E.; Kachale, F.; Kangaude, G. The severity of abortion complications in Malawi. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 128, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levandowski, B.A.; Mhango, C.; Kuchingale, E.; Lunguzi, J.; Katengeza, H.; Gebreselassie, H.; Singh, S. The incidence of induced abortion in Malawi. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2013, 39, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redinger, A.; Nguyen, H. Incomplete abortions. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Abortion Care Guideline; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Cook, S.; de Kok, B.; Odland, M.L. ‘It’sa very complicated issue here’: Understanding the limited and declining use of manual vacuum aspiration for postabortion care in Malawi: A qualitative study. Health Policy Plan. 2017, 32, 305–313. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Medical Management of Abortion; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Dikme, O.; Dikme, O.; Topacoglu, H. Vaginal Bleeding after Use of Single Dose Oral Diclofenac/Misoprostol Com-Bination. Acta Med. 2013, 29, 301. [Google Scholar]

- Krugh, M.M.C. Misoprostol; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgin, Z.; Kömürcü, N. Comparison of the effects and side effects of misoprostol and oxytocin in the postpartum period: A systematic review. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 58, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, J.; Gebreselassie, H.; Mañibo, M.A.; Raisanen, K.; Johnston, H.B.; Mhango, C.; Levandowski, B.A. Costs of postabortion care in public sector health facilities in Malawi: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odland, M.L.; Membe-Gadama, G.; Kafulafula, U.; Jacobsen, G.W.; Kumwenda, J.; Darj, E. The Use of Manual Vacuum Aspiration in the Treatment of Incomplete Abortions: A Descriptive Study from Three Public Hospitals in Malawi. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odland, M.L.; Membe-Gadama, G.; Kafulafula, U.; Odland, J.Ø.; Darj, E. “Confidence comes with frequent practice”: Health professionals’ perceptions of using manual vacuum aspiration after a training program. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odland, M.L.; Rasmussen, H.; Jacobsen, G.W.; Kafulafula, U.K.; Chamanga, P.; Odland, J. Decrease in use of manual vacuum aspiration in postabortion care in Malawi: A cross-sectional study from three public hospitals, 2008–2012. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubo, A.M.; Soto, Z.M.; Haro-Pérez, A.; Hernández Hernández, M.E.; Doyague, M.J.; Sayagués, J.M. Medical versus surgical treatment of first trimester spontaneous abortion: A cost-minimization analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibiyemi, K.F.; Munir’deen, A.I.; Adesina, K.T. Randomised trial of oral misoprostol versus manual vacuum aspiration for the treatment of incomplete abortion at a Nigerian Tertiary Hospital. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2019, 19, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleeve, A.; Byamugisha, J.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K.; Mbona Tumwesigye, N.; Atuhairwe, S.; Faxelid, E.; Klingberg-Allvin, M. Women’s acceptability of misoprostol treatment for incomplete abortion by midwives and physicians-secondary outcome analysis from a randomized controlled equivalence trial at district level in Uganda. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleeve, A.; Nalwadda, G.; Zadik, T.; Sterner, K.; Klingberg-Allvin, M. Morality versus duty—A qualitative study exploring midwives’ perspectives on post-abortion care in Uganda. Midwifery 2019, 77, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K.; Kiggundu, C.; Namugenyi, R.; Klingberg-Allvin, M. Barriers and facilitators in the provision of post-abortion care at district level in central Uganda—A qualitative study focusing on task sharing between physicians and midwives. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izugbara, C.; Wekesah, F.M.; Sebany, M.; Echoka, E.; Amo-Adjei, J.; Muga, W. Availability, accessibility and utilization of post-abortion care in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Health Care Women Int. 2020, 41, 732–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makenzius, M.; Oguttu, M.; Klingberg-Allvin, M.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K.; Odero, T.M.; Faxelid, E. Post-abortion care with misoprostol–equally effective, safe and accepted when administered by midwives compared to physicians: A randomised controlled equivalence trial in a low-resource setting in Kenya. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndembi, A.P.N.; Mekuí, J.; Pheterson, G.; Alblas, M. Midwives and Post-abortion Care in Gabon:“Things have really changed”. Health Hum. Rights 2019, 21, 145. [Google Scholar]

- Sully, E.A.; Madziyire, M.G.; Riley, T.; Moore, A.M.; Crowell, M.; Nyandoro, M.T.; Madzima, B.; Chipato, T. Abortion in Zimbabwe: A national study of the incidence of induced abortion, unintended pregnancy and post-abortion care in 2016. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akaba, G.O.; Abdullahi, H.I.; Atterwahmie, A.A.; Uche, U.I. Misoprostol for treatment of incomplete abortions by gynecologists in Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. Niger. J. Basic Clin. Sci. 2019, 16, 90. [Google Scholar]

| Theme | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Facilitators and barriers to the use of misoprostol for first-trimester incomplete abortion | Health providers’ knowledge of the use of misoprostol for first-trimester incomplete abortion |

| Health providers’ confidence in the use of misoprostol | |

| Experienced benefits of misoprostol in the management of first-trimester incomplete abortion | |

| Availability and accessibility of misoprostol for first-trimester incomplete abortion | |

| Health providers’ satisfaction with the use of misoprostol in post-abortion care | |

| Supportive supervision in the use of misoprostol | |

| Care provided to women with first-trimester incomplete abortion | An encounter with the patient: treatment offered |

| Preferred treatment by the healthcare workers | |

| Experiences of follow-up care of patients treated with misoprostol | |

| Complications | |

| Type of healthcare workers providing medical management | |

| Task shifting |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chakhame, B.M.; Darj, E.; Mwapasa, M.; Kafulafula, U.K.; Maluwa, A.; Chiudzu, G.; Malata, A.; Odland, J.Ø.; Odland, M.L. Experiences of Using Misoprostol in the Management of Incomplete Abortions: A Voice of Healthcare Workers in Central Malawi. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912045

Chakhame BM, Darj E, Mwapasa M, Kafulafula UK, Maluwa A, Chiudzu G, Malata A, Odland JØ, Odland ML. Experiences of Using Misoprostol in the Management of Incomplete Abortions: A Voice of Healthcare Workers in Central Malawi. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912045

Chicago/Turabian StyleChakhame, Bertha Magreta, Elisabeth Darj, Mphatso Mwapasa, Ursula Kalimembe Kafulafula, Alfred Maluwa, Grace Chiudzu, Address Malata, Jon Øyvind Odland, and Maria Lisa Odland. 2022. "Experiences of Using Misoprostol in the Management of Incomplete Abortions: A Voice of Healthcare Workers in Central Malawi" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912045

APA StyleChakhame, B. M., Darj, E., Mwapasa, M., Kafulafula, U. K., Maluwa, A., Chiudzu, G., Malata, A., Odland, J. Ø., & Odland, M. L. (2022). Experiences of Using Misoprostol in the Management of Incomplete Abortions: A Voice of Healthcare Workers in Central Malawi. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912045