‘I Doubt Myself and Am Losing Everything I Have since COVID Came’—A Case Study of Mental Health and Coping Strategies among Undocumented Myanmar Migrant Workers in Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Settings and Study Design

2.2. Data Collection Procedure

2.3. Ethical Consideration

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Survey Participants

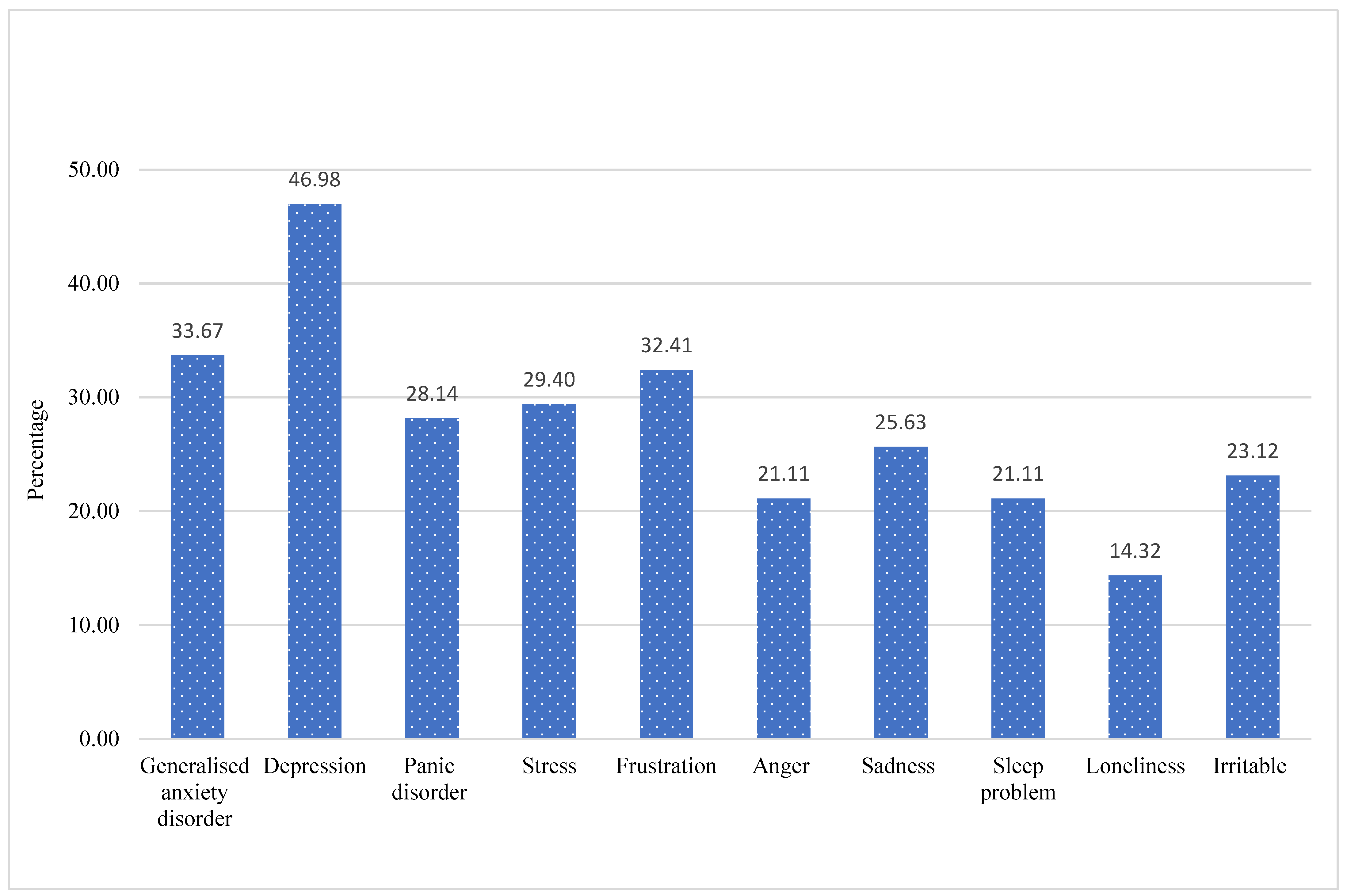

3.2. Migrant Workers’ Mental Health Condition (from Quantitative Survey)

3.3. Major Factors That Influenced Mental Health

3.3.1. Loss of Employment in COVID-19

‘There are no jobs available during COVID-19. Lack of employment is a significant issue since there was no income to survive. I was seriously depressed because I didn’t have the income to feed my children due to job loss’—P9 (F).

‘My mental health deteriorated for around 5 months during the early phases of COVID-19 in 2020. I am disappointed with my future and have lost my interest in living’—P6 (M).

‘I have suffered from depression due to a lack of regular work and income throughout this COVID-19’—P1 (M).

3.3.2. Worries about Susceptibility to COVID-19

‘I doubt myself and am losing everything I have since COVID came. Because the virus may dwell in money, walls, and other places. Although I usually wore a mask and washed my hands frequently, I felt insecure, which caused me mental fatigue. I felt more mentally stressed when the positive cases were confirmed near the community’—FGD1 participant.

‘My mental health was suffering the consequences of my anxiety of losing my job and income if I was infected with COVID-19’—FDG 2 participant.

‘There were times when I couldn’t sleep at all. I feel depressed and anxious about contracting with the COVID-19’—P10 (F).

3.3.3. Increased Infection Risk with COVID-19 and Denied Access to Healthcare

‘When I tested positive for COVID-19, I experienced extreme depression because I lost my job; my entire family also tested positive, making it difficult to sleep and eat’—P5 (M).

‘While my whole family members were diagnosed with COVID-19, we were unable to get medical treatment in a hospital because Myanmar migrant workers were rejected. I was terrified, depressed, and anxious about what might happen and how I would feel. There had been a lot of sadness, since we are not in our home country’—FDG 2 participant.

‘We take several medications on our own during the COVID-19 infection. Due to a lack of access to appropriate medical treatment, I suffered from insomnia, mental depression, and irritation’—FDG 2 participant.

3.3.4. Lockdown and Daily Living Crisis

‘I was also frustrated by the travel restrictions that prohibited going anywhere including to work. In my mind, there are times when I wanted to take my life. I was unable to sleep for a month and was felt like insane’—P9 (F).

‘There are days when there was nothing to eat because I have no money and receive no assistance’—P7 (M).

3.3.5. Worries about Family Members’ Safety from COVID-19 Infection

‘My family is in Myanmar, and I am in Thailand. My mental health has deteriorated dramatically since I worried whether family members at home can handle or protect from COVID-19 infection’—FGD1 participant.

‘In Thailand, I am alone, and my mother is also at home alone. As a consequence, I am concerned for my mother during COVID-19. I sometimes wonder if I have a wing to return home. Sometimes I wish I could go somewhere where no one could hear me scream and cry. I am missing my mother’—FGD1 participant.

3.3.6. Fear of Detention

‘I am worried and afraid of the police rather than contacting COVID-19. I am frightened, and I feel like crazy when I think. Now, the police raid homes and arrest irregular migrant workers, and I cannot sleep because I am afraid of being arrested’—FGD1 participant.

3.3.7. Fear of Next Waves

‘I have been out of work since the COVID-19 outbreak. I am concerned about the next wave if another lockdown would be imposed’—FGD1 participant.

3.4. Coping Strategies of UMMWs for Mental Health Adaptation

3.4.1. Coping Strategies to Avoid Infection and Mental Distress

‘I avoid going to crowded or public places by wearing a mask and washing my hands’—FGD2 participant.

3.4.2. Using Social Media Platforms

‘I was motivated by some motivational Facebook posts. Despite the fact that I did not receive encouragement from others, I improved my mental health by listening to them’—P6 (M).

3.4.3. Chatting with Family Members and Friends

‘I was able to develop my mental health with the encouragement and inspiration from others since I had heard that some individuals were in worse condition than I was’—P8 (F).

‘There were many people at the quarantine center, and we were motivated to be strong and support one another’—FGD1 participant.

3.4.4. Religious Coping

‘I pray every night to overcome depression caused by COVID-19. I occasionally sang a religious song to heal my worries’—P10 (F).

‘I might be able to protect myself. But I am still concerned about whether my family will be secure or infected with COVID-19. I cope with all my trouble through praying to God’—FGD2 participant.

‘I suffered moments of sadness and felt hopeless about my life in many ways. I cannot find employment in Thailand because of the COVID-19. I do not intend to return to Myanmar because the situation worsens following the military coup. Sometimes I felt utterly helpless about how to survive, what to eat, and where to live. So, I spend the entire day praying to God. God has heard my prayer, and I can still manage from various donations for food and shelter’—P3 (M).

‘I pray to God to take away my worries. Since I cannot attend church in person due to social gathering restrictions, I call the pastor and request them to pray for me. We motivate one another and chat about God. As a reason, I do not find it so challenging to handle COVID-19, and I believe it will be over soon’—FGD1 participant.

‘This is the nature of life: something will arrive, and something will depart. By taking care of my health, I can only pray that this pandemic will be ended soo’—FGD1 participant.

3.4.5. Self-Motivation

‘I am not alone facing this pandemic. Other people too. Such thinking allows to overcome my mental health’—FGD2 participant.

‘Because of COVID-19, I experienced depression, frustration, and insomnia. However, I realized that this pandemic affects the entire world, not just myself or my country. If I cannot resist, how can other people too? I am motivating myself to endure this epidemic’—FGD2 participant.

‘As a mother, I keep myself from sinking into depression. We all have a future, and my children do as well. Time will cure this epidemic. So, I try to overcome as much as I can’—P2 (F).

‘Although I was depressed and wanted to commit suicide, I encouraged myself to be strong since I have children, and they must live. I convinced myself that I could do it and not give up no matter what condition’—P9 (F).

‘I was depressed, but not so much to end my life condition. I encouraged myself to survive by telling myself that no one would feed my family if I could not work or survive’—FGD2 participant.

3.4.6. Listening to Music and Playing Mobile Game

‘I listen to music to cope with my mental problem. I also pray to be free soon from COVID-19’—P7 (M).

‘Compared to the early phases of COVID-19, my mental health is improving now. I listen to music, play mobile games, and watch movies to get rid of my depression although I could not go out and interact with my friends’—P6 (M).

4. Discussion

4.1. Coping at a Personal Level

4.2. Coping at a Social Level

4.3. Limitations

5. Practical Policy Implication

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nations, U. International Migrant Stock 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Lancet, T. India under COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet 2020, 395, 1315. [Google Scholar]

- ECDC. Reducing COVID-19 Transmission and Strengthening Vaccine Uptake among Migrant Populations in the EU/EEA; Technical Report; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Moroz, H.; Shrestha, M.; Testaverde, M. Potential Responses to the COVID-19 Outbreak in Support of Migrant Workers; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, N.M.; Friedrichs, M.; Wagstaff, S.; Sage, K.; LaCross, N.; Bui, D.; McCaffrey, K.; Barbeau, B.; George, A.; Rose, C. Disparities in COVID-19 incidence, hospitalizations, and testing, by area-level deprivation—Utah, March 3–July 9, 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liem, A.; Wang, C.; Wariyanti, Y.; Latkin, C.A.; Hall, B.J. The neglected health of international migrant workers in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- News, U. WHO Calls for Action to Provide Migrant and Refugee Healthcare. 2022. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/07/1122872 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- World Health Organization (WHO). COVID-19 Immunization in Refugees and Migrants: Principles and Key Considerations: Interim Guidance; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chantavanich, S.; Vungsiriphisal, P. Myanmar migrants to Thailand: Economic analysis and implications to Myanmar development. In Economic Reforms in Myanmar: Pathways and Prospects; Bangkok Research Center: Bangkok, Thailand, 2012; pp. 213–280. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Thematic Working Group on Migration in Thailand. Thailand Migration Report 2019. Available online: https://thailand.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-06/Thailand-Migration-Report-2019.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- International Organization for Migration. Migration Context 2021. Available online: https://thailand.iom.int/migration-context (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Thepgumpanat, P. Thai Lockdown Sparks Exodus of 60,000 Migrant Workers: Ministry Official. 2020. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-thailand-exodus-idUSKBN21C0ZI (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Pross, C. Migrant Workers in Times of COVID-19: An Empathetic Disaster Response for Myanmar Workers in Thailand. 2021. Available online: https://www.sei.org/perspectives/migrant-workers-covid-disaster-response/ (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Tangsathaporn, P. Migrants Get Rough Deal under COVID. 2021. Available online: https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/2238135/migrants-get-rough-deal-under-covid (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). COVID-19: Impact on Migrant Workers and Country Response in Thailand. 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/asia/publications/issue-briefs/WCMS_741920/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Wiriyapong, N. Don’t Leave Migrant Workers Behind. 2021. Available online: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/2154731/dont-leave-migrant-workers-behind (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Wipatayotin, A. Delta Strain to Dominate in the Capital. 2021. Available online: https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/2140051/delta-strain-to-dominate-in-the-capital (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- IOM. Effects of COVID-19 on Migrants- Survey in Central America and Mexico (June 2020). 2020. Available online: https://dtm.iom.int/reports/effects-covid-19-migrants-survey-central-america-and-mexico-june-2020 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Baloran, E.T. Knowledge, attitudes, anxiety, and coping strategies of students during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Loss Trauma 2020, 25, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara, M.B.; Noom, S.H. Acculturative stress and coping among Burmese women migrant workers in Thailand. AU J. Manag. 2014, 12, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, K.K.; Johnston, J.M. Depression and health-seeking behaviour among migrant workers in Shenzhen. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2015, 61, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.R.; Decker, M.R.; Tol, W.A.; Abshir, N.; Mar, A.A.; Robinson, W.C. Workplace and security stressors and mental health among migrant workers on the Thailand–Myanmar border. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadim, W.; AlOtaibi, A.; Al-Mohaimeed, A.; Ewid, M.; Sarhandi, M.; Saquib, J.; Alhumdi, K.; Alharbi, A.; Taskin, A.; Migdad, M. Depression among migrant workers in Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 206, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Khaled, S.M.; Gray, R. Depression in migrant workers and nationals of Qatar: An exploratory cross-cultural study. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2019, 65, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucci, N.; Traversini, V.; Giorgi, G.; Tommasi, E.; De Sio, S.; Arcangeli, G. Migrant workers and psychological health: A systematic review. Sustainability 2019, 12, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, S.I.; Yee, A.; Rinaldi, A.; Azham, A.A.; Mohd Hairi, F.; Amer Nordin, A.S. Prevalence of common mental health issues among migrant workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htay, M.N.N.; Latt, S.S.; Maung, K.S.; Myint, W.W.; Moe, S. Mental well-being and its associated factors among Myanmar migrant workers in Penang, Malaysia. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2020, 32, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Mehra, A.; Sahoo, S.; Nehra, R.; Grover, S. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on the migrant workers: A cross-sectional survey. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 53, 102252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesornsri, S.; Sitthimongkol, Y.; Punpuing, S.; Vongsirimas, N.; Hegadoren, K.M. Mental health and related factors among migrants from Myanmar in Thailand. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. [JPSS] 2019, 27, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, P.; Islam, B.; Hussain, M.A. COVID-19 lockdown and penalty of joblessness on income and remittances: A study of inter-state migrant labourers from Assam, India. J. Public Aff. 2021, 21, e2470. [Google Scholar]

- Chavan, B.; Sidana, A.; Arun, P.; Rohilla, R.; Singh, G.P.; Solanki, R.; Aneja, J.; Murara, M.K.; Verma, M.; Chakraborty, S. Factors leading to reverse migration among migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multicenter study from Northwest India. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2021, 23, 30398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, J. COVID-19: Migrants face barriers accessing healthcare during the pandemic, report shows. Br. Med. J. 2021, 374, n2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Lindenmeyer, A.; Phillimore, J.; Lessard-Phillips, L. Vulnerable migrants’ access to healthcare in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Public Health 2022, 203, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knights, F.; Carter, J.; Deal, A.; Crawshaw, A.F.; Hayward, S.E.; Jones, L.; Hargreaves, S. Impact of COVID-19 on migrants’ access to primary care and implications for vaccine roll-out: A national qualitative study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2021, 71, e583–e595. [Google Scholar]

- Spiritus-Beerden, E.; Verelst, A.; Devlieger, I.; Langer Primdahl, N.; Botelho Guedes, F.; Chiarenza, A.; De Maesschalck, S.; Durbeej, N.; Garrido, R.; Gaspar de Matos, M. Mental health of refugees and migrants during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of experienced discrimination and daily stressors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UCANews. Thai Authorities Deport Desperate Migrants from Myanmar. 2022. Available online: https://www.ucanews.com/news/thai-authorities-deport-desperate-migrants-from-myanmar/96852 (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Irrawaddy, T. Thai Prisons Crowded with Illegal Myanmar Migrants. 2022. Available online: https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/thai-prisons-crowded-with-illegal-myanmar-migrants.html (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Weller, S.J.; Crosby, L.J.; Turnbull, E.R.; Burns, R.; Miller, A.; Jones, L.; Aldridge, R.W. The negative health effects of hostile environment policies on migrants: A cross-sectional service evaluation of humanitarian healthcare provision in the UK. Wellcome Open Res. 2019, 4, 109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- IOM. Despite Positive Efforts, Too Many Migrants Face Challenges Accessing COVID-19 Vaccines. 2021. Available online: https://www.iom.int/news/despite-positive-efforts-too-many-migrants-face-challenges-accessing-covid-19-vaccines (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Desie, Y.; Habtamu, K.; Asnake, M.; Gina, E.; Mequanint, T. Coping strategies among Ethiopian migrant returnees who were in quarantine in the time of COVID-19: A center-based cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 192. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 46, 5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H.; Li, X. Acculturation and HIV-related sexual behaviours among international migrants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2015, 9, 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, B.C. Coping, acculturation, and psychological adaptation among migrants: A theoretical and empirical review and synthesis of the literature. Health Psychol. Behav. Med.: Open Access J. 2014, 2, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancourt, D.; Finn, S. What Is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Johannes, N.; Vuorre, M.; Przybylski, A.K. Video game play is positively correlated with well-being. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 202049. [Google Scholar]

- Melodia, F.; Canale, N.; Griffiths, M.D. The role of avoidance coping and escape motives in problematic online gaming: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 20, 996–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change1. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westcott, R.; Ronan, K.; Bambrick, H.; Taylor, M. Expanding protection motivation theory: Investigating an application to animal owners and emergency responders in bushfire emergencies. BMC Psychol. 2017, 5, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd, D.L.; Prentice-Dunn, S.; Rogers, R.W. A meta-analysis of research on protection motivation theory. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 407–429. [Google Scholar]

- Weishaar, H.B. Consequences of international migration: A qualitative study on stress among Polish migrant workers in Scotland. Public Health 2008, 122, 1250–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weishaar, H.B. “You have to be flexible”—Coping among polish migrant workers in Scotland. Health Place 2010, 16, 820–827. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S.; Li, X. Responding to the pandemic as a family unit: Social impacts of COVID-19 on rural migrants in China and their coping strategies. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Arya, Y.K.; Joshi, S.; Singh, T.; Kaur, H.; Chauhan, H.; Das, A. Major stressors and coping strategies of internal migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative exploration. Front. Psychol. 2021, 1441. [Google Scholar]

- Magis, K. Community resilience: An indicator of social sustainability. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-L.; Zhang, D.-J.; Zimmerman, M.A. Resilience theory and its implications for Chinese adolescents. Psychol. Rep. 2015, 117, 354–375. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S. Personal control and stress and coping processes: A theoretical analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Olukotun, O.; Gondwe, K.; Mkandawire-Valhmu, L. The mental health implications of living in the shadows: The lived experience and coping strategies of undocumented African migrant women. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Nakonz, J.; Shik, A.W.Y. And all your problems are gone: Religious coping strategies among Philippine migrant workers in Hong Kong. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2009, 12, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tschirhart, N.; Straiton, M.; Ottersen, T.; Winkler, A.S. “Living like I am in Thailand”: Stress and coping strategies among Thai migrant masseuses in Oslo, Norway. BMC Women’s Health 2019, 19, 139. [Google Scholar]

- Dull, V.T.; Skokan, L.A. A cognitive model of religion’s influence on health. J. Soc. Issues 1995, 51, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, J.; Chia, C.; Koh, C.; Chua, B.; Narayanaswamy, S.; Wijaya, L. Healthcare-seeking behaviour, barriers and mental health of non-domestic migrant workers in Singapore. BMJ Glob. Health 2017, 2, e000213. [Google Scholar]

- Slootjes, J.; Keuzenkamp, S.; Saharso, S. Narratives of meaningful endurance–how migrant women escape the vicious cycle between health problems and unemployment. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2018, 6, 21. [Google Scholar]

| Sample Characteristic | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 188 | 47.2 |

| Female | 210 | 52.8 |

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 139 | 34.9 |

| 30–39 | 145 | 36.4 |

| 40–49 | 80 | 20.1 |

| 50 and above | 34 | 8.5 |

| Current employment status | ||

| Unemployed | 156 | 39.2 |

| Employed | 242 | 60.8 |

| Current employment sector (top 5 answers only) | ||

| Construction | 56 | 23.1 |

| Agriculture sector | 49 | 20.2 |

| Domestic work | 34 | 14.0 |

| Factory/garment production | 26 | 10.7 |

| Retail trade and vendor | 14 | 4.8 |

| List of Participants | Gender | Age | Education Background | Religion | COVID-19 Infection | Employment Status during Interview | The Last and Current Employment Sector | Years of Stay in Thailand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In depth interview (n = 11) | ||||||||

| P1 | M | 22 | Primary | Buddhist | No | Unemployed | Seafood processing | 2 |

| P2 | F | 33 | Bachelor | Buddhist | No | Unemployed | Teacher in migrant school | 16 |

| P3 | M | 26 | High school | Christian | No | Unemployed | Garment factory | 11 |

| P4 | F | 46 | Monastic | Muslim | No | Unemployed | Domestic work | 17 |

| P5 | F | 29 | Secondary | Buddhist | Yes | Unemployed | Daily basis | 13 |

| P6 | M | 22 | Secondary | Buddhist | No | Part time | Restaurant | 12 |

| P7 | M | 22 | Primary | Buddhist | No | Part time | Construction | 8 |

| P8 | F | 40 | High school | Buddhist | No | Unemployed | Vendor/self employed | 5 |

| P9 | F | 25 | High school | Buddhist | No | Unemployed | Vendor/self employed | 6 |

| P10 | F | 37 | Secondary | Buddhist | No | Unemployed | Factory | 20 |

| P11 | M | 21 | Primary | Buddhist | No | Part time | Construction | 10 |

| Focus group discussion (n = 2) | ||||||||

| FGD-1 | F | 65 | High school | Christian | Yes | Unemployed | Self-business | 10 |

| FGD-1 | F | 29 | High school | Buddhist | No | Unemployed | Beauty parlor | 6 |

| FGD-1 | M | 50 | Secondary | Buddhist | No | Employed | Agriculture sector/farm | 27 |

| FGD-1 | F | 35 | Monastic | Christian | No | Unemployed | Cleaner at public school | 9 |

| FGD-1 | M | 27 | Secondary | Christian | Yes | Unemployed | Garment factory | 9 |

| FGD-1 | M | 28 | High school | Buddhist | No | Unemployed | Daily basis | 14 |

| FGD-2 | F | 24 | High school | Buddhist | No | Unemployed | Cleaner at hotel | 5 |

| FGD-2 | M | 44 | Secondary | Buddhist | Yes | Employed | Multiple jobs/care workshop | 9 |

| FGD-2 | F | 38 | High school | Buddhist | Yes | Self-business | Convenience store | 15 |

| FGD-2 | M | 54 | Bachelor | Buddhist | Yes | Legal advisor | Legal advisor | 13 |

| FGD-2 | M | 19 | High school | Buddhist | No | Unemployed | Factory | 3 |

| FGD-2 | F | 19 | High school | Buddhist | No | Employed | Factory | 10 |

| Coping Strategies | Percentage | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Follow strict personal protective measures (e.g., masking, handwashing, etc.) | 84.2 | 335 |

| Avoid going out in public places to minimize exposure to COVID-19 | 74.9 | 298 |

| ||

| Do relaxing activities, such as listening to music | 25.1 | 100 |

| Play online games | 12.8 | 51 |

| Avoid media news about COVID-19 and related fatalities | 6.5 | 26 |

| Vent emotions by crying, screaming, etc. | 5.3 | 21 |

| ||

| Praying, worshipping, reading bible, etc. | 29.1 | 116 |

| ||

| Use social media such as Facebook | 37.7 | 150 |

| ||

| Chat with family members and friends to relieve stress and obtain support | 31.9 | 127 |

| ||

| Talk to and motivate myself to face the COVID-19 outbreak with a positive outlook | 21.6 | 86 |

| Try to be busy at work to keep your mind off of COVID-19 | 7.0 | 28 |

| ||

| Consult doctors to reduce stress | 1.0 | 4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khai, T.S.; Asaduzzaman, M. ‘I Doubt Myself and Am Losing Everything I Have since COVID Came’—A Case Study of Mental Health and Coping Strategies among Undocumented Myanmar Migrant Workers in Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215022

Khai TS, Asaduzzaman M. ‘I Doubt Myself and Am Losing Everything I Have since COVID Came’—A Case Study of Mental Health and Coping Strategies among Undocumented Myanmar Migrant Workers in Thailand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):15022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215022

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhai, Tual Sawn, and Muhammad Asaduzzaman. 2022. "‘I Doubt Myself and Am Losing Everything I Have since COVID Came’—A Case Study of Mental Health and Coping Strategies among Undocumented Myanmar Migrant Workers in Thailand" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 15022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215022

APA StyleKhai, T. S., & Asaduzzaman, M. (2022). ‘I Doubt Myself and Am Losing Everything I Have since COVID Came’—A Case Study of Mental Health and Coping Strategies among Undocumented Myanmar Migrant Workers in Thailand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215022