Research on the Influence of Non-Cognitive Ability and Social Support Perception on College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

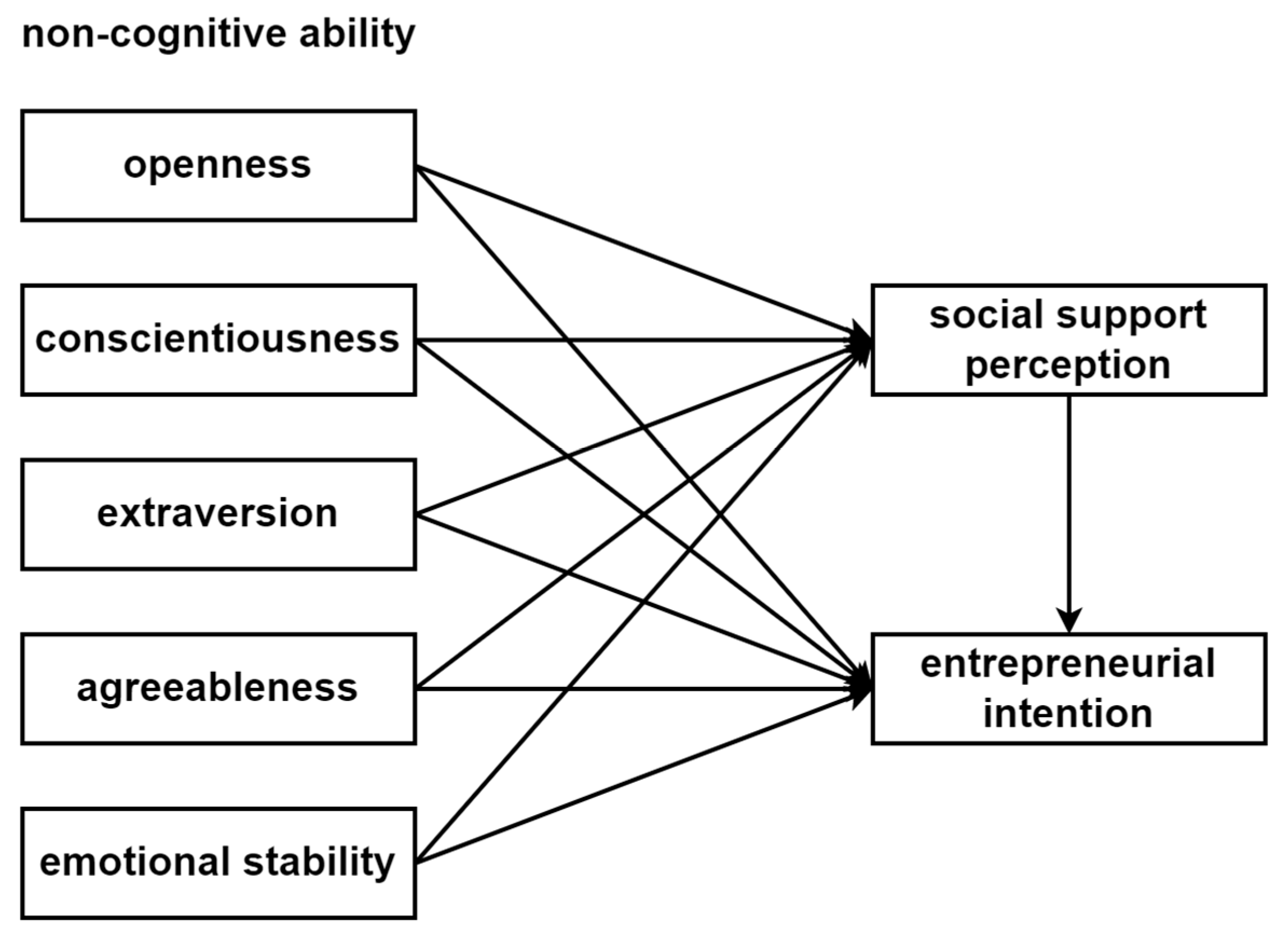

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Concept Definition

2.1.1. The Definition of Non-Cognitive Ability

2.1.2. The Definition of Entrepreneurial Intention

2.1.3. Definition of Social Support Perception

2.2. Theoretical Analysis

2.2.1. The Direct Influence of Various Dimensions of Non-Cognitive Ability on Entrepreneurial Intention

2.2.2. The Mediating Effect of Social Support Perception on Non-Cognitive Ability Dimensions and Entrepreneurial Intention

- 1.

- The direct influence of non-cognitive ability on social support perception

- 2.

- The direct impact of social support perception on entrepreneurial intention

- 3.

- Mediating effect between perception of social support and the influence of non-cognitive ability on entrepreneurial intention

3. Method

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Independent Variable: Non-Cognitive Ability

3.2.2. Mediating Variable: Perception of Social Support

3.2.3. Dependent Variable: College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Empirical Test and Result Analysis

4.1. Analysis of Group Differences

4.1.1. Analysis of Variance

- 1.

- Differences in entrepreneurial intention of different grades

- 2.

- Differences in entrepreneurial intention with frequent participation in entrepreneurial forum lectures

4.1.2. T-test

- 1.

- Analysis of differences in entrepreneurial intention in different school types

- 2.

- Analysis of differences in entrepreneurial intention at the university level and above regarding participation in college student entrepreneurial competitions and winning awards

4.2. Reliability and Validity Test

4.2.1. Reliability Test

4.2.2. Validity Test

4.3. Correlation Analysis

4.4. Structural Equation Model Fitting Index

4.5. Analysis of Data Results

4.5.1. Path Analysis of the Impact of Various Dimensions of Non-Cognitive Ability on Entrepreneurial Intention

4.5.2. Analysis of the Impact Path of Each Dimension of Non-Cognitive Ability on Perception of Social Support

4.5.3. Path Analysis of the Impact of Social Support Perception on Entrepreneurial Intention

4.5.4. Analysis of the Mediating Effect of Social Support Perception

- 1.

- The mediating effect of social support perception on the effect of openness on entrepreneurial intention

- 2.

- The mediating effect of social support perception on the effect of conscientiousness on entrepreneurial intention

- 3.

- The mediating effect of social support perception between extraversion and entrepreneurial intention

- 4.

- The mediating effect of social support perception between agreeableness and entrepreneurial intention

- 5.

- The mediating effect of social support perception on the influence of emotional stability on entrepreneurial intention

5. Discussion

5.1. Openness, Conscientiousness, Extroversion, and Emotional Stability Have Significant Positive Effects on Entrepreneurial Intention

5.2. All Five Dimensions Have a Significant Positive Impact on Perception of Social Support

5.3. Perception of Social Support Has a Positive Impact on Entrepreneurial Intention

5.4. Social Support Perception Acts as a Mediator in the Influence of Non-Cognitive Ability on Entrepreneurial Intention

6. Conclusions

6.1. College Students Should Cultivate the Characteristics of Innovation and Entrepreneurship and Improve Their Entrepreneurial Ability

6.2. Colleges and Universities Should Improve the Quality of Entrepreneurship Education and Promote Entrepreneurial Actions

6.3. Create a Good Entrepreneurial Environment for College Students to Start a Business and Improve Their Willingness to Start a Business

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, G.H. Role of Innovation and Entrepreneurship Education in Improving Employability of Medical University Students. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2017, 13, 8149–8154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.B.; Li, Q.Q.; Zhou, T.; Li, C.; Gu, C.H.; Zhao, X.L. Social Creativity and Entrepreneurial Intentions of College Students: Mediated by Career Adaptability and Moderated by Parental Entrepreneurial Background. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 893351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzaffar, H. Does passion ignite intentions? Understanding the influence of entrepreneurial passion on the entrepre-neurial career intentions of higher education students. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2021, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, W.J. Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Distructive. J. Polit. Econ. 1990, 98, 893–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.H. An Extended Model of the Theory of Planned Behavior: An Empirical Study of Entrepreneurial Intention and Entrepreneurial Behavior in College Students. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 627818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.F.; Huang, J.H.; Gao, S.Y. Relationship Between Proactive Personality and Entrepreneurial Intentions in College Students: Mediation Effects of Social Capital and Human Capital. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 627818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, H.; Kim, H. Does National Gender Equality Matter? Gender Difference in the Relationship between Entrepreneurial Human Capital and Entrepreneurial Intention. Sustainability 2022, 14, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debarliev, S.; Janeska-Iliev, A.; Stripeikis, O.; Zupan, B. What can education bring to entrepreneurship? Formal versus non-formal education. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2022, 60, 219–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, J.J.; Rubinstein, Y. The importance of noncognitive skills: Lessons from the GED testing program. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, J.J.; Stixrud, J.; Urzua, S. The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior. J. Labor Econ. 2006, 24, 411–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schick, A.; Steckel, R.H. Height, Human Capital, and Earnings: The Contributions of Cognitive and Noncognitive Ability. J. Hum. Cap. 2015, 9, 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.D. From Poverty to Prosperity: College Education, Noncognitive Abilities, and First-Job Earnings. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 2018, 50, 53–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopelliti, M.; Tiberio, L. Homesickness in University Students: The Role of Multiple Place Attachment. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAndrea, D.C.; Ellison, N.B.; LaRose, R.; Steinfield, C.; Fiore, A. Serious social media: On the use of social media for improving students’ adjustment to college. Internet High. Educ. 2012, 15, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert, R.F.; Link, A.N. In Search of the Meaning of Entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 1989, 1, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbard, M.N. Professor Hébert on Entrepreneurship. J. Libert. Stud. 1985, 2, 281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Pana, M.-C.; Fanea-Ivanovici, M. Institutional Arrangements and Overeducation: Challenges for Sustainable Growth. Evidence from the Romanian Labour Market. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, Q.E. The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. J. Econ. Lit. 2000, 38, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettke, P.J.; Coyne, C.J.; Leeson, P.T. Institutional stickiness and the new development economics. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2008, 67, 331–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucel, A.; Vilalta-Bufi, M. University Program Characteristics and Education-Job Mismatch. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2019, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, L. Not the right job, but a secure one: Over-education and temporary employment in France, Italy and Spain. Work. Employ. Soc. 2010, 24, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, R.S. Testing Baumol: Institutional quality and the productivity of entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2008, 23, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettke, P.; Fink, A. Institutions first. J. Inst. Econ. 2011, 7, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turmo-Garuz, J.; Bartual-Figueras, M.T.; Sierra-Martinez, F.-J. Factors Associated with Overeducation Among Recent Graduates During Labour Market Integration: The Case of Catalonia (Spain). Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 144, 1273–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J. Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth. In Handbook of Economic Growth; Aghion, P., Durlauf, S.N., Eds.; North Holland Publishing Co.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 1A, pp. 386–464. ISBN 9780444520418. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Understanding the Process of Economic Change; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 103–115. ISBN 0-691-11805-1. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, L.X.; Liu, J.; Ding, C.; Hollon, S.D.; Shao, B.T.; Zhang, Q. The relation of self-supporting personality, enacted social support, and perceived social support. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, E.M.; Mutum, D.S.; Javadi, H.H. The impact of the institutional environment and experience on social entrepre-neurship: A multi-group analysis. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 1329–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol. Monogr. 1966, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchione, M.; Alessandri, G.; Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G. Higher-order factors of the big five and basic values: Empirical and theoretical relations. Br. J. Psychol. 2011, 102, 478–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, N.; Joseph, S. Big 5 correlates of three measures of subjective well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2003, 34, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; Bartram, D. Aggregate personality and organizational competitive advantage. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 90, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Lin, C.P.; Zhao, G.X.; Zhao, D.L. Research on the Effects of Entrepreneurial Education and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy on College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Duysters, G.; Cloodt, M. The role of entrepreneurship education as a predictor of university students’ entre-preneurial intention. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2014, 10, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoi, N.H.; Tuu, H.H.; Olsen, S.O.; Le, A.N.H. Patterns of Forming Entrepreneurial Intention: Evidence in Vietnam. Entrep. Res. J. 2021, 11, 20180184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asoh, D.A.; Rivers, P.A.; McCleary, K.J.; Sarvela, P. Entrepreneurial propensity in health care: Models and propositions for empirical research. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, A.; Ashourizadeh, S.; Sheikhi, S.; Rexhepi, G. Entrepreneurial propensity for market analysis in the time of COVID-19: Benefits from individual entrepreneurial orientation and opportunity confidence. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; House, J.S. Stress, social support, control and coping: A social epidemiological view. WHO Reg. Publ. Eur. Ser. 1991, 37, 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Nestadt, D.F.; Alicea, S.; Petersen, I.; John, S.; Myeza, N.P.; Nicholas, S.W.; Cohen, L.G.; Holst, H.; Bhana, A.; McKay, M.M.; et al. HIV+ and HIV- youth living in group homes in South Africa need more psychosocial support. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud. 2013, 8, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Heung, K.O.U. A Study on the Relationship between Psychological Resilience and Social Support of Chinese College Students. J. Learn. -Cent. Curric. Instr. 2020, 20, 663–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.P.; Lien, M.C.; Jaw, B.S.; Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, Y.S.; Kung, S.H. Interrelationship of expatriate employees’ person-ality, cultural intelligence, cross-cultural adjustment, and entrepreneurship. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2019, 47, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoncic, B.; Kregar, T.B.; Singh, G.; DeNoble, A.F. The Big Five Personality-Entrepreneurship Relationship: Evidence from Slovenia. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 819–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postigo, A.; Cuesta, M.; Garcia-Cueto, E.; Prieto-Diez, F.; Muniz, J. General versus specific personality traits for predicting entrepreneurship. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 182, 111094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.H.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Li, D.Y.; Zhang, J.Q.; Li, J.W. The Relationship between Big Five Personality and Social Well-Being of Chinese Residents: The Mediating Effect of Social Support. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 613659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, K.E.; Murano, D.; Burrus, J.; Casillas, A. Multimethod Support for Using the Big Five Framework to Organize Social and Emotional Skills. Assessment 2021, 72, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branje, S.J.T.; van Lieshout, C.F.M.; van Aken, M.A.G. Relations between Big Five personality characteristics and perceived support in adolescents’ families. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caines, V.; Earl, J.K.; Bordia, P. Self-Employment in Later Life: How Future Time Perspective and Social Support Influence Self-Employment Interest. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S. Prone to Progress: Using Personality to Identify Supporters of Innovative Social Entrepreneurship. J. Public Policy Mark. 2012, 31, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nga, J.K.H.; Shamuganathan, G. The Influence of Personality Traits and Demographic Factors on Social Entrepreneurship Start Up Intentions. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo, R.J.M.; Abella, M.C. Well-being and personality: Facet-level analyses. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.J.; Long, Y.Z.; Fu, M.H. Study on the influence of non-cognitive ability on the citizenship capability of peasant workers. Northwest Popul. J. 2020, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Dai, X.Y. Development of the chinese adjectives scale of big-five factor personality I: Theoretical framework and assessment reliability. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 23, 381–385. [Google Scholar]

- Neneh, B.N.B. From entrepreneurial intentions to behavior: The role of anticipated regret and proactive personality. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 112, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, J.A.; Burg, M.M.; Barefoot, J.; Williams, R.B.; Haney, T.; Zimet, G. Social support, type A behavior, and coronary artery disease. Psychosom. Med. 1987, 49, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Wang, Z. Ming. Confirmatory Factor Aanalysis of Entrepreneurial Intention’s Dimension Structure. Chin. J. Ergon. 2006, 1, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Park, I.J. Influence of proactive personality on career self-efficacy. J. Employ. Couns. 2017, 54, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Project | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 234 | 52 |

| Female | 216 | 48 | |

| Grade | Freshman | 93 | 20.7 |

| Sophomore | 105 | 23.3 | |

| Junior year | 99 | 22 | |

| Senior year | 153 | 34 | |

| Type of School | Undergraduate | 354 | 78.7 |

| Specialist | 96 | 21.3 |

| Dimension | Subdimension | Index | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Openness | Curiosity | C1: Interested in many different things | 3.69 | 1.118 |

| C2: A thoughtful person | 3.78 | 1.145 | ||

| C3: Hope to experience a new way of life | 3.75 | 1.052 | ||

| Action force | C4: Likes to take on challenges | 3.74 | 1.049 | |

| C5: Activities organized by participating units | 3.71 | 1.082 | ||

| C6: Have their own hobbies and be able to stick to them | 3.73 | 1.055 | ||

| Imagination | C7: Can find smart ways to do things | 3.68 | 1.073 | |

| C8: Imaginative people | 3.69 | 1.023 | ||

| C9: Be creative and come up with new ideas | 3.7 | 1.085 | ||

| Conscientiousness | Sense of responsibility | C10: I can concentrate on completing the work | 3.88 | 0.929 |

| C11: Trustworthy | 4.03 | 0.964 | ||

| C12: People around me praise me for being responsible | 3.98 | 0.999 | ||

| Organized | C13: Be organized | 4.05 | 1.087 | |

| C14: Habit of keeping things neat and orderly | 3.98 | 0.947 | ||

| C15: Have a plan | 3.94 | 0.915 | ||

| Effort level | C16: At work, I try my best to do everything | 4.01 | 0.963 | |

| C17: Efficient, work from beginning to end | 4.11 | 1.105 | ||

| C18: Perseverance and perseverance to get things done | 3.97 | 0.964 | ||

| C19: Work hard to achieve your goals | 4.03 | 0.971 | ||

| C20: People who constantly demand improvement | 3.97 | 0.966 | ||

| Extraversion | Social contact | C20: I like to make friends | 3.69 | 1.192 |

| C21: Talkative | 3.62 | 1.021 | ||

| C22: I will not reject attending gatherings with many people | 3.7 | 1.116 | ||

| Decisive | C23: Dare to express one’s opinion | 3.67 | 1.131 | |

| C24: Strong and confident character | 3.61 | 1.029 | ||

| C25: Affect others | 3.69 | 1.105 | ||

| Vitality | C26: When I’m around, I’m usually not cold | 3.67 | 1.088 | |

| C27: Energetic | 3.65 | 1.105 | ||

| C28: Passionate | 3.69 | 1.141 | ||

| Agreeableness | Altruism | C29: Willing to pay time cost for others | 3.85 | 1.106 |

| C30: Make people around you feel at ease | 3.79 | 1.089 | ||

| C31: Do my best to help others | 3.71 | 1.01 | ||

| Compliance | C32: Obey social order | 3.75 | 1.146 | |

| C33: Willing to make friends with locals | 3.73 | 1.038 | ||

| C34: Always be polite to others | 3.77 | 1.101 | ||

| Trust | C35: If others have bad experiences, I will be very sympathetic | 3.72 | 1.079 | |

| C36: Think of people in the best way | 3.78 | 1.085 | ||

| C37: Easy to get close to others | 3.73 | 1.062 | ||

| Emotional Stability | Anxiety | C38: Rarely feel anxious | 3.86 | 1.076 |

| C39: Calm and good at dealing with pressure | 3.78 | 1.008 | ||

| C40: Don’t worry too much | 3.73 | 0.97 | ||

| Depression | C41: Be satisfied with yourself | 3.9 | 1.122 | |

| C42: Feel safe in life | 3.79 | 1.077 | ||

| C43: Rarely unhappy in life | 3.83 | 1.022 | ||

| C44: Stay positive despite setbacks | 3.8 | 0.986 | ||

| Vulnerability | C45: Mood is not easy to swing | 3.81 | 1.106 | |

| C46: Rarely gets angry with others | 3.78 | 1.133 | ||

| C47: Can control one’s emotions | 3.8 | 1.038 |

| Dimension | Index | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Support | B1: My family can help me in a concrete way | 3.69 | 1.118 |

| B2: I am able to get emotional help and support from my family when needed | 3.78 | 1.145 | |

| B3: I can talk to my family about my problems | 3.75 | 1.052 | |

| B4: My family is willing to help me make decisions | 3.74 | 1.049 | |

| Friends Support | B5: My friends can really help me | 3.88 | 0.929 |

| B6: I can count on my friends in times of trouble | 4.03 | 0.964 | |

| B7: My friends can share happiness and sadness with me | 3.98 | 0.999 | |

| B8: I can discuss my problems with my friends | 4.05 | 1.087 | |

| Other Support | B9: Some people (teachers, relatives, classmates) will be by my side when I have a problem | 3.69 | 1.192 |

| B10: I can share happiness and sadness with some people (teachers, relatives, classmates) | 3.62 | 1.021 | |

| B11: Some people (teachers, relatives, classmates) are a real source of comfort when I’m in trouble | 3.7 | 1.116 | |

| B12: There are people in my life (teachers, relatives, classmates) who care about my feelings | 3.67 | 1.131 |

| Dimension | Index | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Feasibility | A1: I started a business because it gave me the opportunity to make a difference | 3.69 | 1.118 |

| A2: I already have the interpersonal skills needed to start a business | 3.78 | 1.145 | |

| A3: I feel energized when working in a creative, passionate and dynamic environment | 3.75 | 1.052 | |

| A4: I have the self-confidence needed to start a business | 3.74 | 1.049 | |

| A5: I already have the organizational and management skills needed to start a business | 3.71 | 1.082 | |

| A6: I already have the ideas needed to start a business | 3.73 | 1.055 | |

| Entrepreneurial Propensity | A7: I like to do challenging work | 3.88 | 0.929 |

| A8: I think my experience can meet the needs of future work | 4.03 | 0.964 | |

| A9: I have now started to prepare to start a business | 3.98 | 0.999 | |

| A10: The current entrepreneurial environment is suitable for me to start a business | 4.05 | 1.087 | |

| A11: I am excited when there are unusual solutions to work problems | 3.98 | 0.947 | |

| Entrepreneurial Desirability | A12: I have communicated my intention to start a business with my family or friends | 3.69 | 1.192 |

| A13: I already have the teamwork skills needed to start a business | 3.62 | 1.021 | |

| A14: I’m already spending time learning about entrepreneurship | 3.7 | 1.116 | |

| A15: I already have the perseverance needed to start a business | 3.67 | 1.131 | |

| A16: I already have the financial conditions needed to start a business | 3.61 | 1.029 | |

| A17: I already have the learning skills needed to start a business | 3.69 | 1.105 |

| Variable | Category | N | Mean | Standard Deviation | F | Salience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Intention | Freshman | 93 | 3.262 | 0.588 | 4.687 | 0.003 |

| Sophomore | 105 | 3.355 | 0.557 | |||

| Junior year | 99 | 3.356 | 0.578 | |||

| Senior year | 153 | 3.520 | 0.519 |

| Variable | Category | N | Mean | Standard Deviation | F | Salience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Intention | Never participate | 88 | 3.283 | 0.604 | 3.362 | 0.01 |

| Participate occasionally | 198 | 3.358 | 0.545 | |||

| Uncertain | 45 | 3.366 | 0.504 | |||

| Participate often | 63 | 3.493 | 0.602 | |||

| Always participate | 56 | 3.591 | 0.508 |

| Category | N | Mean | Standard Deviation | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Intention | Undergraduate | 354 | 3.3544 | 0.56121 | −2.741 | 0.006 |

| Specialist | 96 | 3.5306 | 0.5491 |

| Category | N | Mean | Standard Deviation | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Intention | Yes | 164 | 3.487 | 0.546 | 2.733 | 0.007 |

| NO | 286 | 3.338 | 0.566 |

| Variable/Dimension | Number of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Intention | 17 | 0.88 |

| Entrepreneurial Feasibility | 6 | 0.904 |

| Entrepreneurial Propensity | 5 | 0.883 |

| Entrepreneurial Desirability | 6 | 0.914 |

| Social Support | 12 | 0.921 |

| Family Support | 4 | 0.882 |

| Friends Support | 4 | 0.9 |

| Other Support | 4 | 0.877 |

| Non-Cognitive Abilities | 48 | 0.956 |

| Openness | 9 | 0.944 |

| Conscientiousness | 11 | 0.943 |

| Extraversion | 9 | 0.915 |

| Agreeableness | 9 | 0.928 |

| Emotional Stability | 10 | 0.948 |

| Variable | KMO | Bartlett’s Sphericity Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate Chi-Square | df | Sig. | ||

| Entrepreneurial Intention | 0.917 | 4434.751 | 136 | 0.000 |

| Social Support | 0.921 | 3502.37 | 66 | 0.000 |

| Non-Cognitive Abilities | 0.961 | 15285.919 | 1128 | 0.000 |

| Overall Questionnaire | 0.952 | 24583.693 | 2926 | 0.000 |

| Measurement Item | Ingredients | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| A1 | 0.778 | ||||||||||

| A2 | 0.791 | ||||||||||

| A3 | 0.8 | ||||||||||

| A4 | 0.745 | ||||||||||

| A5 | 0.786 | ||||||||||

| A6 | 0.775 | ||||||||||

| A7 | 0.703 | ||||||||||

| A8 | 0.747 | ||||||||||

| A9 | 0.745 | ||||||||||

| A10 | 0.759 | ||||||||||

| A11 | 0.751 | ||||||||||

| A12 | 0.757 | ||||||||||

| A13 | 0.78 | ||||||||||

| A14 | 0.755 | ||||||||||

| A15 | 0.784 | ||||||||||

| A16 | 0.801 | ||||||||||

| A17 | 0.802 | ||||||||||

| B1 | 0.714 | ||||||||||

| B2 | 0.75 | ||||||||||

| B3 | 0.753 | ||||||||||

| B4 | 0.773 | ||||||||||

| B5 | 0.741 | ||||||||||

| B6 | 0.686 | ||||||||||

| B7 | 0.748 | ||||||||||

| B8 | 0.748 | ||||||||||

| B9 | 0.708 | ||||||||||

| B10 | 0.734 | ||||||||||

| B11 | 0.703 | ||||||||||

| B12 | 0.724 | ||||||||||

| C1 | 0.795 | ||||||||||

| C2 | 0.79 | ||||||||||

| C3 | 0.773 | ||||||||||

| C4 | 0.769 | ||||||||||

| C5 | 0.764 | ||||||||||

| C6 | 0.778 | ||||||||||

| C7 | 0.817 | ||||||||||

| C8 | 0.785 | ||||||||||

| C9 | 0.81 | ||||||||||

| C10 | 0.736 | ||||||||||

| C11 | 0.723 | ||||||||||

| C12 | 0.716 | ||||||||||

| C13 | 0.719 | ||||||||||

| C14 | 0.696 | ||||||||||

| C15 | 0.729 | ||||||||||

| C16 | 0.734 | ||||||||||

| C17 | 0.755 | ||||||||||

| C18 | 0.748 | ||||||||||

| C19 | 0.727 | ||||||||||

| C20 | 0.743 | ||||||||||

| C21 | 0.772 | ||||||||||

| C22 | 0.757 | ||||||||||

| C23 | 0.706 | ||||||||||

| C24 | 0.723 | ||||||||||

| C25 | 0.682 | ||||||||||

| C26 | 0.761 | ||||||||||

| C27 | 0.731 | ||||||||||

| C28 | 0.731 | ||||||||||

| C29 | 0.792 | ||||||||||

| C30 | 0.74 | ||||||||||

| C31 | 0.714 | ||||||||||

| C32 | 0.661 | ||||||||||

| C33 | 0.707 | ||||||||||

| C34 | 0.717 | ||||||||||

| C35 | 0.709 | ||||||||||

| C36 | 0.682 | ||||||||||

| C37 | 0.727 | ||||||||||

| C38 | 0.783 | ||||||||||

| C39 | 0.776 | ||||||||||

| C40 | 0.782 | ||||||||||

| C41 | 0.757 | ||||||||||

| C42 | 0.748 | ||||||||||

| C43 | 0.758 | ||||||||||

| C44 | 0.732 | ||||||||||

| C45 | 0.748 | ||||||||||

| C46 | 0.774 | ||||||||||

| C47 | 0.779 | ||||||||||

| C48 | 0.771 | ||||||||||

| Eigenvalues | 21.93 | 4.71 | 4.61 | 4.12 | 3.61 | 3.50 | 3.0 | 2.42 | 1.98 | 1.55 | 1.06 |

| Variance Explained Rate | 28.48% | 6.11% | 5.99% | 5.35% | 4.68% | 4.54% | 3.89% | 3.15% | 2.57% | 2.01% | 1.38% |

| Total Explanation Rate | 68.16% | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Openness | 1 | ||||||

| Conscientiousness | 0.389 ** | 1 | |||||

| Extraversion | 0.226 ** | 0.337 ** | 1 | ||||

| Agreeableness | 0.412 ** | 0.527 ** | 0.313 ** | 1 | |||

| Emotional Stability | 0.341 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.287 ** | 0.464 ** | 1 | ||

| Social Support Perception | 0.373 ** | 0.438 ** | 0.349 ** | 0.466 ** | 0.444 ** | 1 | |

| Entrepreneurial Intention | 0.398 ** | 0.497 ** | 0.422 ** | 0.441 ** | 0.496 ** | 0.563 ** | 1 |

| Way | Standardized Path Coefficient | S.E. | C.R. | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Support Perception | <--- | Openness | 0.142 | 0.043 | 2.738 | 0.006 ** |

| Social Support Perception | <--- | Conscientiousness | 0.148 | 0.052 | 2.478 | 0.013 * |

| Social Support Perception | <--- | Extraversion | 0.17 | 0.041 | 3.362 | *** |

| Social Support Perception | <--- | Agreeableness | 0.214 | 0.055 | 3.493 | *** |

| Social Support Perception | <--- | Emotional Stability | 0.212 | 0.045 | 3.799 | *** |

| Entrepreneurial Intention | <--- | Openness | 0.176 | 0.028 | 2.941 | 0.003 ** |

| Entrepreneurial Intention | <--- | Conscientiousness | 0.185 | 0.033 | 2.707 | 0.007 ** |

| Entrepreneurial Intention | <--- | Extraversion | 0.28 | 0.028 | 4.548 | *** |

| Entrepreneurial Intention | <--- | Agreeableness | 0.018 | 0.034 | 0.266 | 0.79 * |

| Entrepreneurial Intention | <--- | Emotional Stability | 0.216 | 0.03 | 3.318 | *** |

| Entrepreneurial Intention | <--- | Social Support Perception | 0.446 | 0.048 | 5.24 | *** |

| Parameter | Estimate | Lower | Upper | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Openness-Social Support Perception-Entrepreneurial Intention | 0.063 | 0.018 | 0.12 | 0.004 |

| Conscientiousness-Social Support Perception-Entrepreneurial Intention | 0.066 | 0.012 | 0.129 | 0.01 |

| Extraversion-Social Support Perception-Entrepreneurial Intention | 0.076 | 0.032 | 0.145 | 0.001 |

| Agreeableness-Social Support Perception-Entrepreneurial Intention | 0.095 | 0.037 | 0.176 | 0.001 |

| Emotional Stability-Social Support Perception-Entrepreneurial Intention | 0.094 | 0.047 | 0.171 | 0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Si, W.; Yan, Q.; Wang, W.; Meng, L.; Zhang, M. Research on the Influence of Non-Cognitive Ability and Social Support Perception on College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911981

Si W, Yan Q, Wang W, Meng L, Zhang M. Research on the Influence of Non-Cognitive Ability and Social Support Perception on College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):11981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911981

Chicago/Turabian StyleSi, Wentao, Qi Yan, Wenshu Wang, Lin Meng, and Maocong Zhang. 2022. "Research on the Influence of Non-Cognitive Ability and Social Support Perception on College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 11981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911981