Access and Participation of Students with Disabilities: The Challenge for Higher Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptualisation

3. Results, State of Play, Access, and Participation of Students with Disabilities in Higher Education

4. Method

4.1. Search Strategy

4.2. Selection Criteria

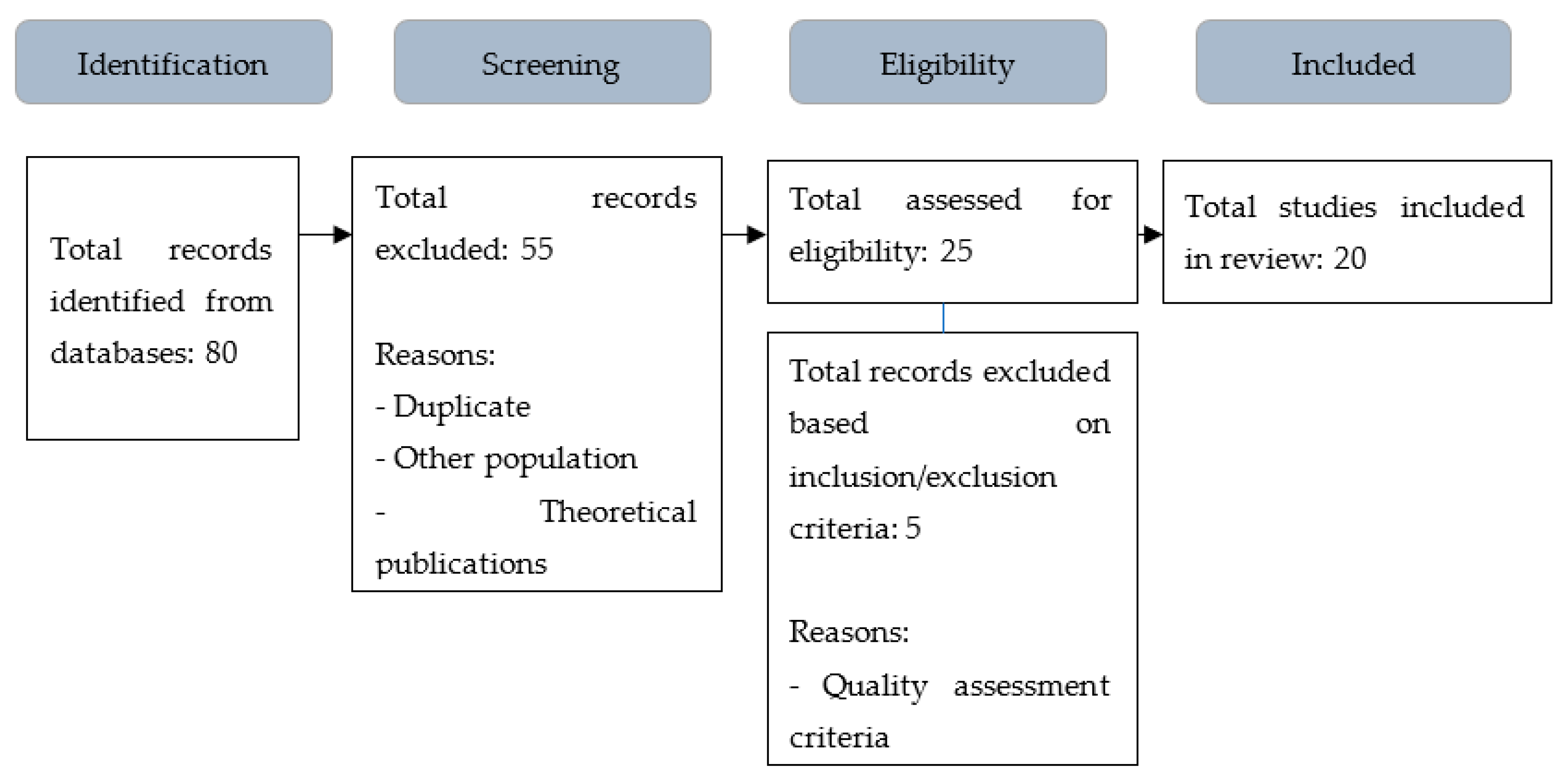

4.3. Literature Selection

4.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

5. Results

6. Discussion

- -

- Infrastructure: Students with disabilities present educational needs that must be addressed for them to successfully access education, as the existence of these barriers can impede accessibility for these students [35,45,51]. Architectural or infrastructural barriers are the most common access barriers for students with disabilities. This may be since university facilities are mostly old buildings, therefore, their spaces are not adapted to the needs of students [50], affecting their mobility.

- -

- Teaching–learning process: Studies highlight several barriers to learning. Among them, the lack of preparation of teachers to use a methodology that promotes inclusion in the classroom according to the needs of their students stands out [39]. These results coincide with other studies that have been carried out on the lack of teacher training to cater for these students in higher education [52,53]. They also mention the difficulties of access to material resources, since in most cases they are not adapted to their needs or are limited [34,40,46,54].

- -

- -

- In this line, and to answer the third research question posed, the way to facilitate a successful access to university education for these students, the following aspects must be addressed:

- -

- Infrastructure: Students with disabilities demand multiple supports related to access to higher education, mainly related to access and mobility on campus. The elimination of the different architectural barriers, such as the absence of spaces reserved for people with disabilities, the absence of ramps, inadequate signage, or acoustic barriers in classrooms, will facilitate the movement and permanence of these students at the university [30,42,48].

- -

- Teaching–learning process: It is necessary to generate a new organisational response in the attention to diversity and in teacher training [33,49]. Current trends in education point out that all students can be included in education through inclusion programmes, despite their educational needs, offering different opportunities to these students [55], promoting methodological changes in university institutions, and fostering inclusive education. Among these, the incorporation of Universal Design for Learning stands out to increase the participation of these students [50], as most of the resources and materials are not adapted to their needs. This would allow them to work with the rest of their classmates. Recent studies highlight the incorporation of information and communication technologies as potentially beneficial tools for the inclusion and participation of students with disabilities [36].

- -

- On the other hand, to promote the training of teaching staff in the acquisition of competences to cater for the diversity of their students, training courses, and the modification of the specific training plans that are developed in the different universities are necessary [56], which are usually scarce or nonexistent.

- -

- Institutional management: All students present difficulties during the educational process, therefore, it is necessary to provide assistance services for students with disabilities, in order to offer specialised support and guidance to these students [44]. Thus, assistance services for students with disabilities should be created in all university institutions, or at least, the possibility for all students who need it to have a person or scholar to help them with their integration into the university [31,47].

7. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ainscow, M.; Slee, R.; Best, M. Editorial: The Salamanca statement: 25 years on. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 23, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. Evidence of the Link between Inclusive Education and Social Inclusion: A Review of the Literature; European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education: Odense, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Empowering Children with Disabilities for the Enjoyment of Their Human Rights, Including through Inclusive Education; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ramberg, J.; Watkins, A. Exploring inclusive education across Europe: Some insights from the European agency statistics on inclusive education. Fire Forum Int. Res. Educ. 2020, 6, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacono, T.; Keefe, M.; Kenny, A.; Mckinstry, C. A document review of exclusio-Tnary practices in the context of australian school education policy. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2019, 16, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2001: Mental Health: New Understanding, New hope; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Darrow, A. Barriers to effective inclusion and strategies to overcome them. Gen. Music Today 2009, 22, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, C.; Moriña, A. Barriers and Facilitators for the Educational Inclusion of Persons with Intellectual Disabilities. Siglo Cero 2021, 52, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivik, J.; McComas, J.; Laflamme, M. Barriers and facilitators to inclusive education as reported by students with physical disabilities and their parents. Except. Child. 2002, 61, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez, C.; Sandoval, M.; Sánchez, S.; Simón, C.; Moriña, A.; Morgado, B.; Moreno-Medina, I.; García, J.A.; Díaz-Gandasegui, V.; Elizalde San Miguel, B. Evaluación de la inclusión en educación superior mediante indicadores. REICE. Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Y Cambio En Educ. 2021, 19, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Castro, J. Between barriers and enablers: The experiences of university students with disabilities. Sinéctica 2019, 53, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yssel, N.; Pak, N.; Beilke, J. A Door Must Be Opened: Perceptions of Students with Disabilities in Higher Education. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2016, 63, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcain, E.; Medina, M. Hacia una educación universitaria inclusiva: Realidad y retos. Rev. Digit. Investig. Docencia Univ. 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, L.; Preyde, M. The lived experience of students with an invisible disability at a Canadian university. Disabil. Soc. 2013, 28, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriña, A.; Cotán Fernández, A. Educación Inclusiva y Enseñanza Superior desde la Mirada de Estudiantes con Diversidad Funcional. Rev. Digit. Investig. Docencia Univ. 2017, 11, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L. Developing inclusive learning to improve the engagement, belonging, retention, and success of students from diverse groups. In Widening Higher Education Participation. A Global Perspective; Shah, E.M., Bennett, A., Southgate, E., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 135–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hewett, R.; Douglas, G.; McLinden, M.; Keil, S. Developing an inclusive learning environment for students with visual impairment in higher education: Progressive mutual accommodation and learner experiences in the United Kingdom. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2017, 32, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.; Loreman, T.; Simi, J. Stakeholder perspectives on barriers and facilitators of inclusive education in the solomon islands. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2017, 17, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesech, J.; Nayar, S. Teacher strategies for promoting acceptance and belonging in the classroom: A New zealand study. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 25, 1140–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Batanero, J.M. TIC y Discapacidad: Investigación e Innovación Educativa; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Boynton, l.; Mahon, J. Secondary teachers’ experiences with students with disabi-lities: Examining the global landscape. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2018, 22, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, A.; Carballo, R.; López-Gavira, R. Improving the academic experience of students with disabilities in higher education: Faculty members of Social Sciences and Law speak out. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2021, 34, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunbury, S. Disability in higher education do reasonable adjustments contribute to an inclusive curriculum? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 964–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriña, A.; Perera, V.H.; Melero, N. Difficulties and reasonable adjustments carried out by Spanish faculty members to include students with disabilities. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2020, 47, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moswela, E.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Asking for too much? The voices of students with disabilities in Botswana. Disabil. Soc. 2011, 26, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manterola, C.; Astudillo, P.; Arias, E.; Claros, N. Revisiones sistemáticas de la literatura. Qué se debe saber acerca de ellas. Cirugía Española 2013, 91, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoke, D.; Yang, S. Social Network Analysis; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moriña Díez, A.; Molina Romo, V. La universidad a análisis: Las voces del alumnado con discapacidad. Rev. Enseñanza Univ. 2011, 37, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nava-Caballero, E.M. The Access and the integration of the students with disability of Leon’s University. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2011, 23, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J. Access and participation in higher education of students with disabilities: Access to what? Aust. Educ. Res. 2011, 38, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo González, A. Inclusion of students with disabilities into the university. Challenges and opportunities. Rev. Latinoam. Educ. Inclusiva 2012, 6, 227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Opini, B. Barriers to Participation of Women Students with Disabilities in University Education in Kenya. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 2012, 25, 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- McEwan, R.C.; Downie, R. College Success of Students with Psychiatric Disabilities: Barriers of Access and Distraction. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 2013, 26, 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Zubilllaga del Río, A.; Alba Pastor, C.; Sánchez Hípola, M.P. Technology as a tool to respond to diversity in the university: Analysis of disability as a differentiating factor in the access and use of ICT among college students. Rev. Fuentes 2013, 13, 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, L. Higher education and disability: Exploring student experiences. Cogent Educ. 2016, 3, 1256142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, O.; Soto, X.; Barría, C.; Lucero, X.; Mella, D.; Santana, Y.; Seguel, E. An qualitative study of the adaptation process and inclusion of a group of students with disabilities from higher education at University of Magallanes. Magallania 2016, 44, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Heiman, T.; Fichten, C.S.; Olenik-Shemesh, D.; Keshet, N.S.; Jorgensen, M. Access and perceived ICT usability among students with disabilities attending higher education institutions. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2017, 22, 2727–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsalem, G.M.; Abu Doush, I. Access Education: What is needed to have accessible higher education for students with disabilities in Jordan? Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2018, 33, 541–561. [Google Scholar]

- Majoko, T.; Dunn, M.W. Participation in higher education: Voices of students with disabilities. Cogent Educ. 2018, 5, 1542761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Molina, G.A.; Valenzuela Zambrano, B. Access and continuity of students with disability in Chilean universities. Sinéctica 2019, 53, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansay, N.N.; Moreira, L.C. Policies for access to higher education for students with disabilities in Chile and Brazil. Rev. Ibero-Am. Estud. Educ. Araraquara 2020, 15, 539–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, Y.; Chan, C.C.; Hillaluddin, A.H.; Ramli, F.Z.A.; Saad, Z.M. Improving inclusion of students with disabilities in Malaysian higher education. Disabil. Soc. 2019, 35, 1145–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, A.M.B.; Naami, A. Access to Higher education in Ghana: Examining experiences through the lens of students with mobility disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2019, 68, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, L.M. Specific learning disabilities: Challenges for meaningful access and participation at higher education institutions. J. Educ. 2021, 85, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, L.A.; Madaus, J.W.; Lalor, A.R.; Javitz, H.S. Effect of accessing supports on higher education persistence of students with disabilities. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2021, 14, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpigelman, C.N.; Mor, S.; Sachs, D.; Schreuer, N. Supporting the development of students with disabilities in higher education: Access, stigma, identity, and power. Stud. High. Educ. 2021, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle-Flórez, R.E.; de Caso Fuentes, A.M.; Baelo, R.; García-Martín, S. Faculty of education professors’ perception about the inclusion of university students with disabilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Maldonado, E. Educational inclusion of students in situation of disability in higher education: A systematic review. Rev. Interuniv. 2020, 31, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales, A.; Soto, V.; Villafañe, G. Learning barriers for students with disabilities in a chilean university. Student demands—Institutional challenges. Actual. Investig. Educ. 2016, 16, 67–96. [Google Scholar]

- Nimante, D.; Baranova, S.; Stramkale, L. The university administrative staff perception of inclusion in higher education. Acta Pedagog. Vilnesia 2021, 46, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Batanero, J.M.; Montenegro Rueda, M.; Fernández Cerero, J.; Tadeu, P. Formación del Profesorado y TIC para el Alumnado Con Discapacidad: Una Revisión Sistemática. Rev. Bras. Educ. Espec. 2020, 26, 711–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, G.S.; Bouck, E.C. Examining Postsecondary Education Predictors and Participation for Students with Learning Disabilities. J. Learn. Disabil. 2015, 50, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnsdóttir, K. Belonging to higher education: Inclusive education for students with intellectual disabilities. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2017, 32, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.H.; Borges, M.L.; Gonçalves, T. Attitudes towards inclusion in higher education in a Portuguese university. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2018, 22, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, P.R.; Gasset, D.I.; Garcia, A.C. Inclusive education at a Spanish university: The voice of students with intellectual disability. Disabil. Soc. 2020, 36, 376–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, C.X.; Gómez, V.; Cañedo, C.M. Access and retention in higher education of students with disabilities in Ecuador. Form. Univ. 2012, 5, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

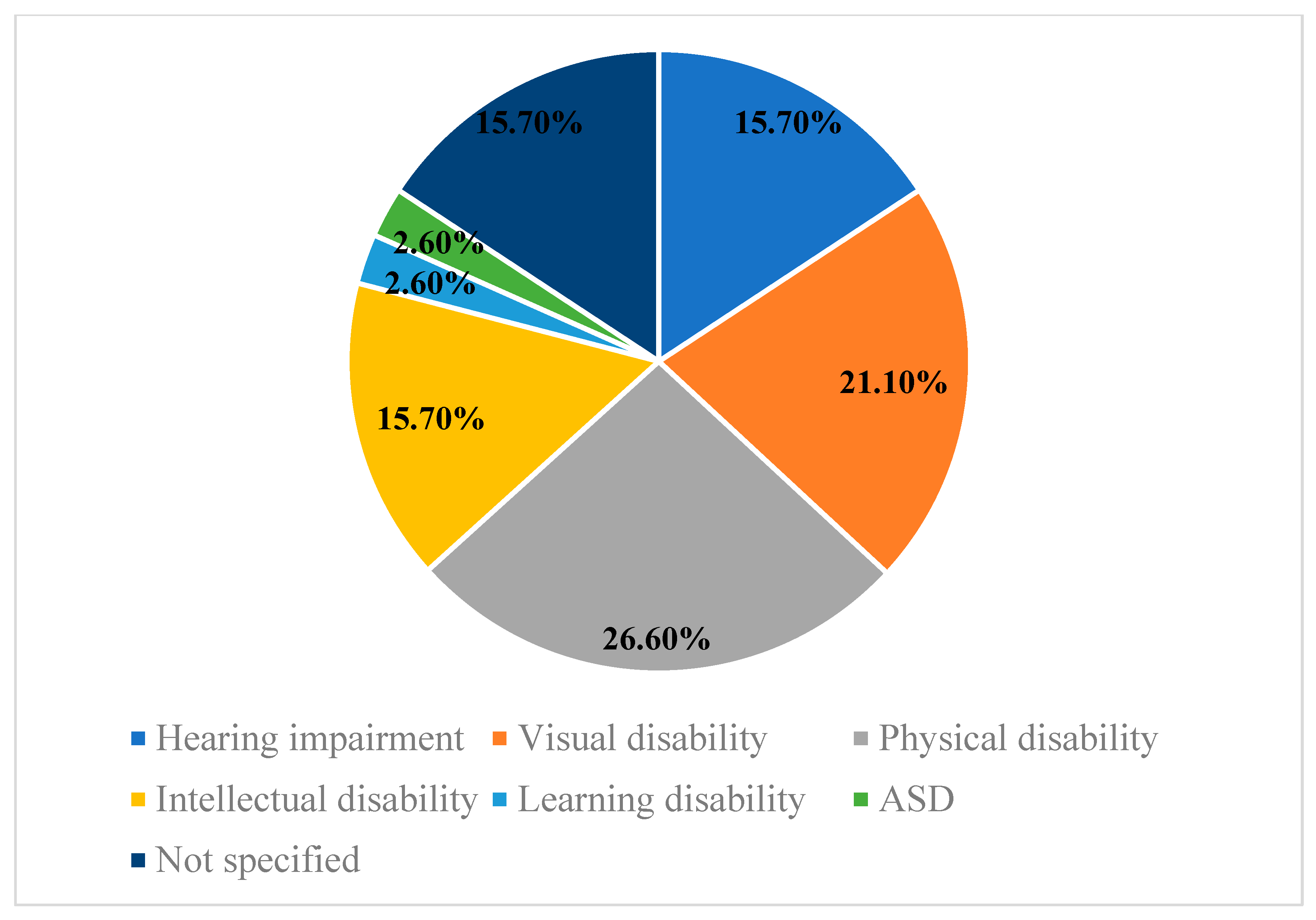

| Study | Year | Method | Disability Type | Country | Main Topic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moriña Díez and Molina Romo [30] | 2011 | Qualitative | Hearing, visual, physical, and intellectual disabilities | Spain | Barriers to university access |

| Nava-Caballero [31] | 2011 | Qualitative | Hearing, visual, physical, and intellectual disabilities | Spain | Facilitating factors in access and adaptation |

| Ryan [32] | 2011 | Qualitative | Not specified | Australia | Facilitating factors in access and adaptation |

| Ocampo González [33] | 2012 | Quantitative | Not specified | Chile | Barriers to university access |

| Opini [34] | 2012 | Qualitative | Not specified | Canada | Barriers to university access |

| McEwan and Downie [35] | 2013 | Quantitative | Intellectual disability | Canada | Barriers to university access |

| Zubillaga del Río et al. [36] | 2013 | Quantitative | Not specified | Spain | Facilitating factors in access and adaptation |

| Kendall and Tarman [37] | 2016 | Qualitative | Hearing impaired | UK | Facilitating factors in access and adaptation |

| Palma et al. [38] | 2016 | Qualitative | Hearing, visual, physical, and intellectual disability | Chile | Facilitating factors in access and adaptation |

| Heiman et al. [39] | 2017 | Quantitative | Not specified | Israel | Facilitating factors in access and adaptation |

| Alsalem and Abu Doush [40] | 2018 | Qualitative | Not specified | Jordan | Barriers to university access |

| Majoko and Dunn [41] | 2018 | Qualitative | ASD, physical, hearing, and visual disability. | South Africa | Facilitating factors in access and adaptation |

| Rodríguez Molina & Valenzuela Zambrano [42] | 2019 | Qualitative | Physical, visual disability, and ASD | Chile | Barriers in access to university |

| Ansay and Moreira [43] | 2020 | Qualitative | Physical disability | Chile | Barriers in access to university |

| Yusof et al. [44] | 2020 | Qualitative | Physical and visual disability | Malaysia | Barriers to access and adaptation |

| Braun & Naami [45] | 2021 | Qualitative | Physical disability | USA | Barriers in access to university |

| Dreyer [46] | 2021 | Qualitative | Learning disability | South Africa | Barriers in access to university |

| Newman et al. [47] | 2021 | Quantitative | Intellectual disability and hearing impairments | USA | Barriers in access to university |

| Shpigelman et al. [48] | 2021 | Qualitative | Physical, visual, hearing, and intellectual disabilities. | Israel | Barriers in access to university |

| Valle-Flórez et al. [49] | 2021 | Quantitative | Hearing, visual, physical, and intellectual disabilities. | Spain | Facilitating factors in access and adaptation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández-Batanero, J.M.; Montenegro-Rueda, M.; Fernández-Cerero, J. Access and Participation of Students with Disabilities: The Challenge for Higher Education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11918. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911918

Fernández-Batanero JM, Montenegro-Rueda M, Fernández-Cerero J. Access and Participation of Students with Disabilities: The Challenge for Higher Education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):11918. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911918

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-Batanero, José María, Marta Montenegro-Rueda, and José Fernández-Cerero. 2022. "Access and Participation of Students with Disabilities: The Challenge for Higher Education" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 11918. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911918

APA StyleFernández-Batanero, J. M., Montenegro-Rueda, M., & Fernández-Cerero, J. (2022). Access and Participation of Students with Disabilities: The Challenge for Higher Education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 11918. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911918