Breastfeeding, Community Vulnerability, Resilience, and Disasters: A Snapshot of the United States Gulf Coast

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

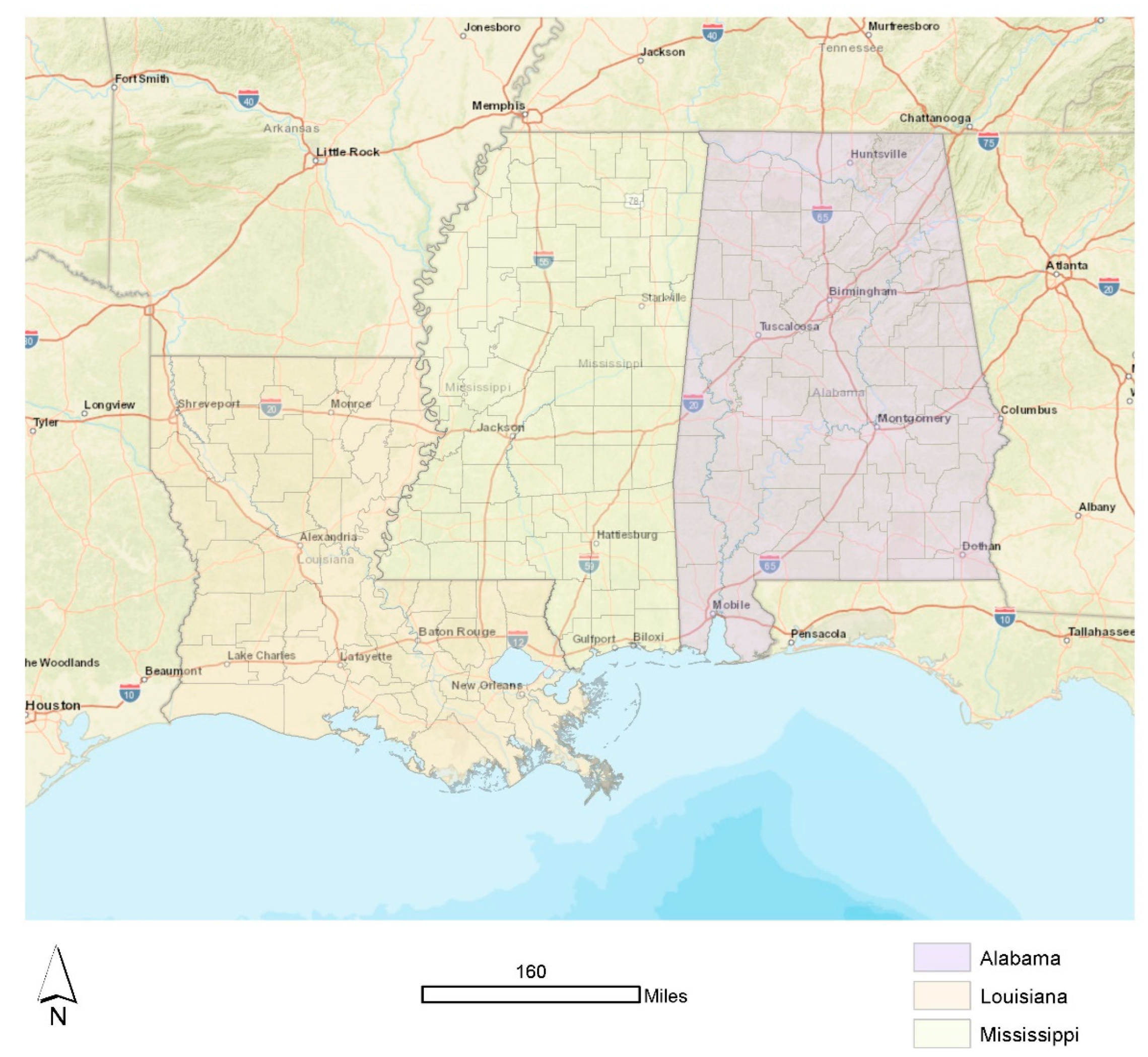

2.1. Setting and Relevant Context

2.2. Sample

2.3. Measurement and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Data Analysis

3.2. Confirmatory Data Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cappelli, F.; Costantini, V.; Consoli, D. The Trap of Climate Change-Induced “Natural” Disasters and Inequality. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 70, 102329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnayake Mudiyanselage, S.; Davis, D.; Kurz, E.; Atchan, M. Infant and Young Child Feeding during Natural Disasters: A Systematic Integrative Literature Review. Women Birth 2022, S1871519221001992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gribble, K. Supporting the Most Vulnerable Through Appropriate Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergencies. J. Hum. Lact. 2018, 34, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gribble, K.D.; Berry, N.J. Emergency Preparedness for Those Who Care for Infants in Developed Country Contexts. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2011, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, F.; Schultink, W. Breastfeeding in Emergencies: A Question of Survival; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. Available online: https://apps.who.int/mediacentre/commentaries/breastfeeding-in-emergencies/en/index.html (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Childs, J. 7 Million Texas Without Clean Water Due to Winter Storms. Weather Channel. 19 February 2021. Available online: https://weather.com/news/news/2021-02-18-winter-storm-water-outages-power-outages-ice-snow-south (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Underwood, L. H.R.6555—DEMAND Act of 2022; GovTrack: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Kavilanz, P. Baby Formula Shortage Has Some Families Scrambling. CNN. 8 February 2021. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2022/02/08/business/baby-formula-shortages/index.html (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Kavilanz, P. Parents Are Desperate after Baby Formula Recall Wipes out Supply. CNN. 24 February 2021. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2022/02/24/business/baby-formula-parents-desperate/index.html (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Davies, I.P.; Haugo, R.D.; Robertson, J.C.; Levin, P.S. The Unequal Vulnerability of Communities of Color to Wildfire. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, M.; Flores-Haro, G.; Zucker, L. The (in)Visible Victims of Disaster: Understanding the Vulnerability of Undocumented Latino/a and Indigenous Immigrants. Geoforum 2020, 116, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, K.; Steinhäuser, J.; Wilfling, D.; Goetz, K. Quality of Health Care for Refugees—A Systematic Review. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2019, 19, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, W.M.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Jamieson, D.J.; Ventura, S.J.; Farr, S.L.; Sutton, P.D.; Mathews, T.J.; Hamilton, B.E.; Shealy, K.R.; Brantley, D.; et al. Health Concerns of Women and Infants in Times of Natural Disasters: Lessons Learned from Hurricane Katrina. Matern. Child Health J. 2007, 11, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadkovic, S.; Lombardo, N.; Cole, D.C. Breastfeeding and Climate Change: Overlapping Vulnerabilities and Integrating Responses. J. Hum. Lact. 2021, 37, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, S.E.; Chase, J.; Branco, M.P.; Park, B. The Effect of Mass Evacuation on Infant Feeding: The Case of the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfire. Matern. Child Health J. 2018, 22, 1826–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, S.; Suji, M.; Southall, H.G. Maternal Perceptions of Infant Feeding and Health in the Context of the 2015 Nepal Earthquake. J. Hum. Lact. 2018, 34, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirani, S.A.A.; Richter, S.; Salami, B.O.; Vallianatos, H. Breastfeeding in Disaster Relief Camps: An Integrative Review of Literature. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 42, E1–E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MirMohamadaliIe, M.; Khani Jazani, R.; Sohrabizadeh, S.; Nikbakht Nasrabadi, A. Barriers to Breastfeeding in Disasters in the Context of Iran. Prehospital Dis. Med. 2019, 34, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Oglio, I.; Marchetti, F.; Mascolo, R.; Amadio, P.; Gawronski, O.; Clemente, M.; Dotta, A.; Ferro, F.; Garofalo, A.; Salvatori, G.; et al. Breastfeeding Protection, Promotion, and Support in Humanitarian Emergencies: A Systematic Review of Literature. J. Hum. Lact. 2020, 36, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. Percent of Total Population in Poverty; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-poverty-well-being/ (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Census. Census Quick Facts; United States Census Bureau: Suitland, MD, USA, 2022.

- Garnier, R.; Bento, A.I.; Rohani, P.; Omer, S.B.; Bansal, S. Feeding the Disparities: The Geography and Trends of Breastfeeding in the United States; preprint. Epidemiology 2018, 451435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubesic, T.H.; Durbin, K.M. A Spatial Analysis of Breastfeeding and Breastfeeding Support in the United States: The Leaders and Laggards Landscape. J. Hum. Lact. 2019, 35, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Breastfeeding Report Card: United States 2020; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/pdf/2020-breastfeeding-report-card-h.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- NOAA. Historical Hurricane Storm Tracks; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Seattle, WA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://coast.noaa.gov/hurricanes/#map=4/32/-80 (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Hotez, P.J.; Murray, K.O.; Buekens, P. The Gulf Coast: A New American Underbelly of Tropical Diseases and Poverty. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, G.; Shapley, D.; Yang, T.-C.; Wang, D. Lost in the Black Belt South: Health Outcomes and Transportation Infrastructure. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191 (Suppl. S2), 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esri. USA Counties; Environmental Systems Research Institute: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Breastfeeding Initiation Rates and Maps by County; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/county/breastfeeding-initiation-rates.html (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- BFUSA. Find a Baby-Friendly Hospital or Birthing Center near You; Baby-Friendly USA: Claremore, OK, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.babyfriendlyusa.org/for-parents/find-a-baby-friendly-facility/ (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- FEMA. The National Risk Index; Federal Emergency Management Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.fema.gov/flood-maps/products-tools/national-risk-index (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- FEMA. National Risk Index Technical Documentation; Federal Emergency Management Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_national-risk-index_technical-documentation.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- HVRI. Social Vulnerability Index (SOVI); University of South Carolina Hazards and Vulnerability Research Institute: Columbia, SC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://tinyurl.com/2z6xdp2z (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Cutter, S.L.; Boruff, B.J.; Shirley, W.L. Social Vulnerability to Environmental Hazards *: Social Vulnerability to Environmental Hazards. Soc. Sci. Q. 2003, 84, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HVRI. Baseline Resilience Indicators for Communities. University of South Carolina Hazards and Vulnerability Research Institute. 2019. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/yc4ztrz5 (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- MacQueen, J. Some Methods for Classification and Analysis of Multivariate Observations. Berkeley Symp. Math. Stat. Probab. 1967, 1, 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, R.; Rey, S.; Grubesic, T.H. A Probabilistic Approach to Address Data Uncertainty in Regionalization. Geogr. Anal. 2021, 54, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. Under the Hood Issues in the Specification and Interpretation of Spatial Regression Models. Agric. Econ. 2002, 27, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleifstein, M. A Hurricane Katrina Today Could Cause $175–200 Billion in Damages, Major Insurer Says; NOLA.com: New Orleans, LA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Anstey, E.H.; Chen, J.; Ela m-Evans, L.D.; Perrine, C.G. Racial and Geographic Differences in Breastfeeding—United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 66, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, E.C.; Damio, G.; LaPlant, H.W.; Trymbulak, W.; Crummett, C.; Surprenant, R.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Promoting Equity in Breastfeeding through Peer Counseling: The US Breastfeeding Heritage and Pride Program. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiodu, I.V.; Bugg, K.; Palmquist, A.E.L. Achieving Breastfeeding Equity and Justice in Black Communities: Past, Present, and Future. Breastfeed. Med. 2021, 16, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Pérez, S.; Hromi-Fiedler, A.; Adnew, M.; Nyhan, K.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Impact of Breastfeeding Interventions among United States Minority Women on Breastfeeding Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grubesic, T.H.; Durbin, K.M. Breastfeeding Support: A Geographic Perspective on Access and Equity. J. Hum. Lact. 2017, 33, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubesic, T.H.; Durbin, K.M. The Complex Geographies of Telelactation and Access to Community Breastfeeding Support in the State of Ohio. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapinos, K.; Kotzias, V.; Bogen, D.; Ray, K.; Demirci, J.; Rigas, M.A.; Uscher-Pines, L. The Use of and Experiences With Telelactation Among Rural Breastfeeding Mothers: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Min | Mean | Max | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breastfeeding initiation | 213 | 25.70 | 60.96 | 89.30 | 11.87 |

| Social vulnerability score | 213 | 3.15 | 38.67 | 69.45 | 9.88 |

| Community resilience score | 213 | 48.82 | 53.93 | 64.67 | 2.713.93 |

| Estimated annual loss score | 213 | 3.93 | 14.74 | 52.55 | 7.16 |

| Overall risk score | 213 | 0.70 | 11.76 | 49.29 | 5.41 |

| Baby-Friendly hospitals (dummy) | 44 | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- |

| Cluster | Average Risk Score | Average Breastfeeding Initiation Rate | Within-Cluster Sum of Squares |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 (Low Risk, Moderate Initiation) [n = 77] | 9.689 | 58.98 | 21.674 |

| Cluster 2 (Moderate Risk, Low Initiation) [n = 45] | 11.945 | 44.213 | 26.65 |

| Cluster 3 (Moderate Risk, Moderate Initiation) [n = 43] | 15.93 | 68.379 | 25.585 |

| Cluster 4 (Low Risk, High Initiation) [n = 43] | 7.703 | 73.49 | 19.936 |

| Cluster 5 (High Risk, High Initiation) [n = 7] | 31.605 | 71.471 | 17.902 |

| Within-Cluster Sum of Squares | 111.749 | ||

| Between Cluster Sum of Squares | 312.251 | ||

| Ratio of Between to Total Sum of Squares | 0.736 | ||

| Total Sum of Squares | 424 |

| Independent Variable | Model 1 (Vulnerability, Resilience, and Support) | Model 2 (Vulnerability, Resilience, Risk, and Support |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | 21.5889 (0.103) | 39.002 (0.005) * |

| Social vulnerability | −0.6085 (0.000) * | −0.6248 (0.000) * |

| Community resilience | 1.1568 (0.000) * | 0.7642 (0.004) * |

| Baby-Friendly hospitals (dummy) | 3.6437 (0.005) * | 1.6677 (0.246) |

| Estimated annual loss | ----- | 0.3184 (0.001) * |

| Lambda | 0.5950 (0.000) * | 0.5578 (0.000) * |

| R-squared | 0.6763 | 0.6869 |

| AIC | 1443.61 | 1436.08 |

| Degrees of freedom | 209 | 208 |

| Breusch–Pagan test | 7.7159 (0.052) | 14.0037 (0.021) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grubesic, T.H.; Durbin, K.M. Breastfeeding, Community Vulnerability, Resilience, and Disasters: A Snapshot of the United States Gulf Coast. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11847. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911847

Grubesic TH, Durbin KM. Breastfeeding, Community Vulnerability, Resilience, and Disasters: A Snapshot of the United States Gulf Coast. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):11847. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911847

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrubesic, Tony H., and Kelly M. Durbin. 2022. "Breastfeeding, Community Vulnerability, Resilience, and Disasters: A Snapshot of the United States Gulf Coast" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 11847. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911847

APA StyleGrubesic, T. H., & Durbin, K. M. (2022). Breastfeeding, Community Vulnerability, Resilience, and Disasters: A Snapshot of the United States Gulf Coast. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 11847. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911847