Exploring the Suicide Mechanism Path of High-Suicide-Risk Adolescents—Based on Weibo Text Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

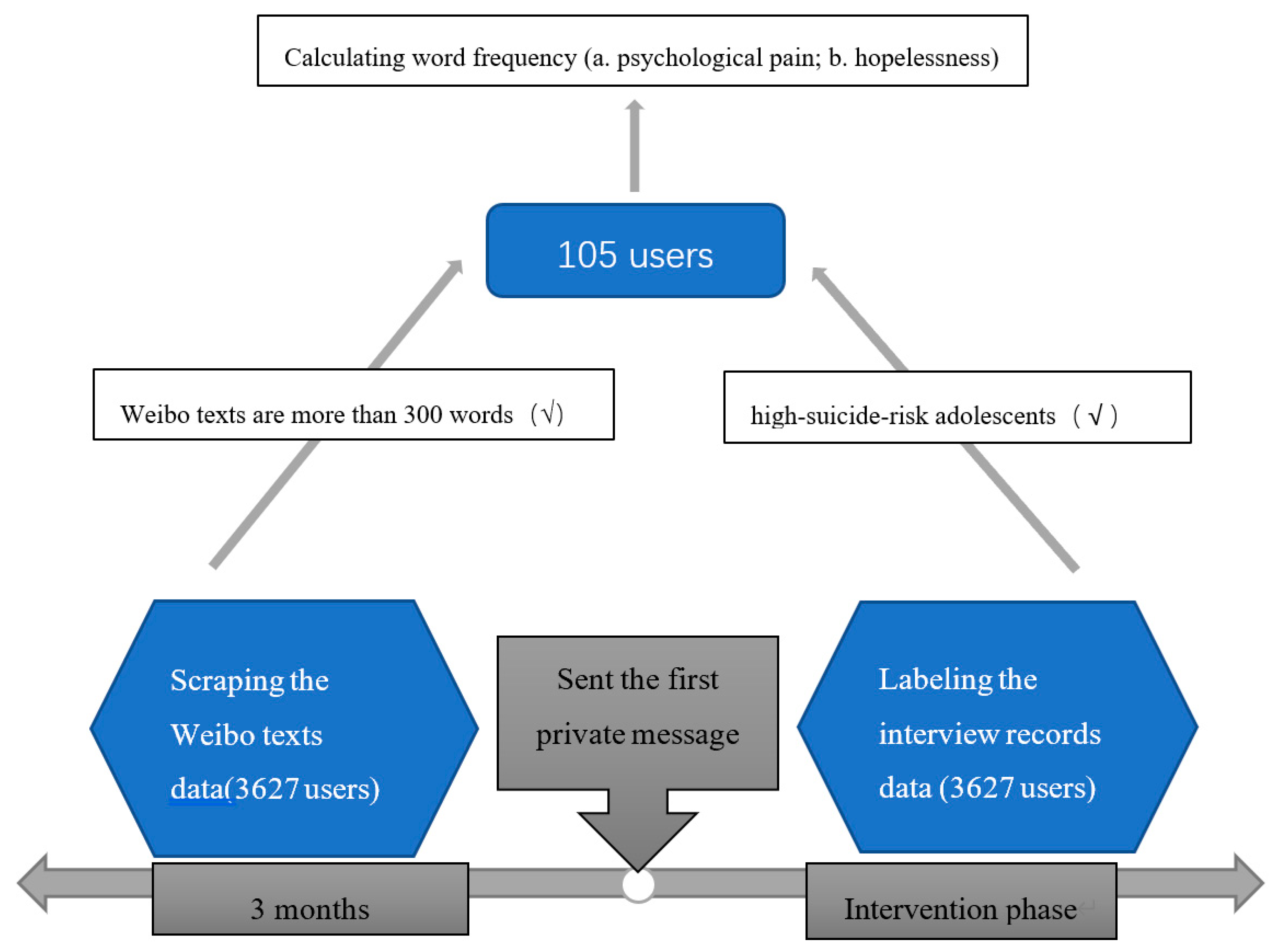

2.1. Participants

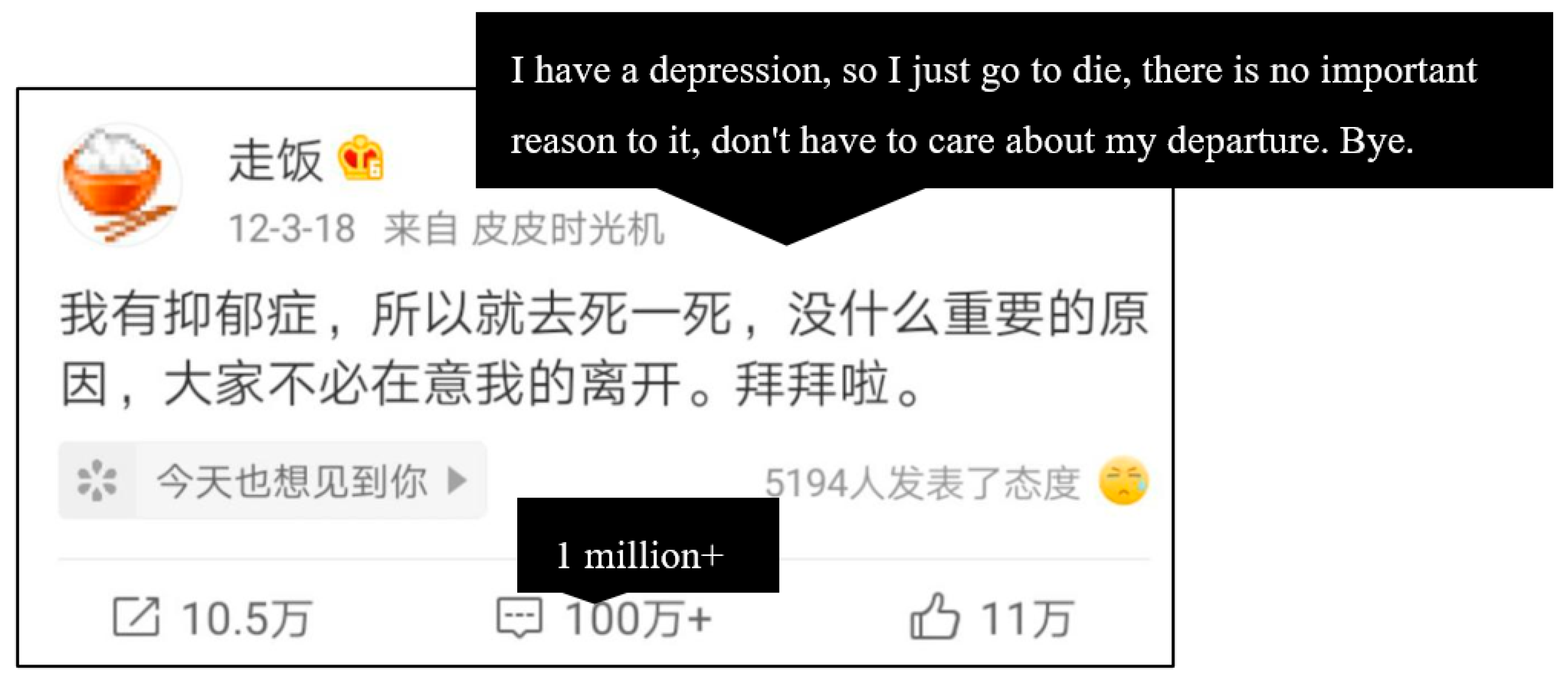

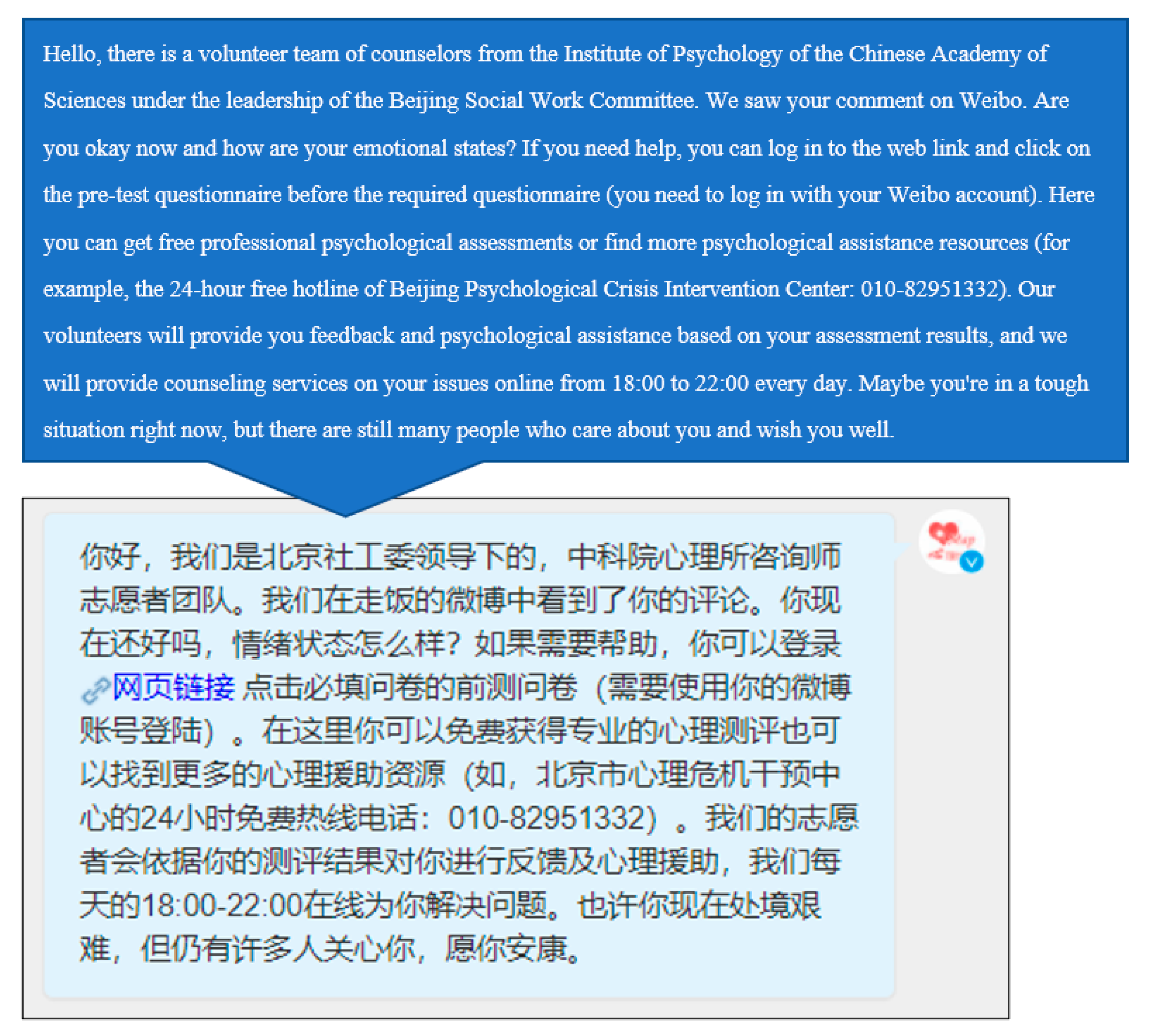

2.2. Online Psychological Assistance Project

2.3. Data Collection and Processing

2.3.1. Labeling the Interview Records Data

- (1)

- Determining whether the user was in adolescent stages (junior high school, high school, college), and retaining the data labeled as the adolescents.

- (2)

- Determining whether the user was diagnosed with mental illness by a psychiatrist, had a history of mental illness, or was taking medication for mental illness, and labeling a user had a mental illness or not as a 0/1 dummy variable.

- (3)

- Coding the suicide stages (depressed mood, suicide ideation, suicide plan, suicide attempt) of adolescents, and marking the suicide stages as 1, 2, 3 and 4, an ordered categorical variable.

2.3.2. Getting the Weibo Text Data

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Qualitative Analysis

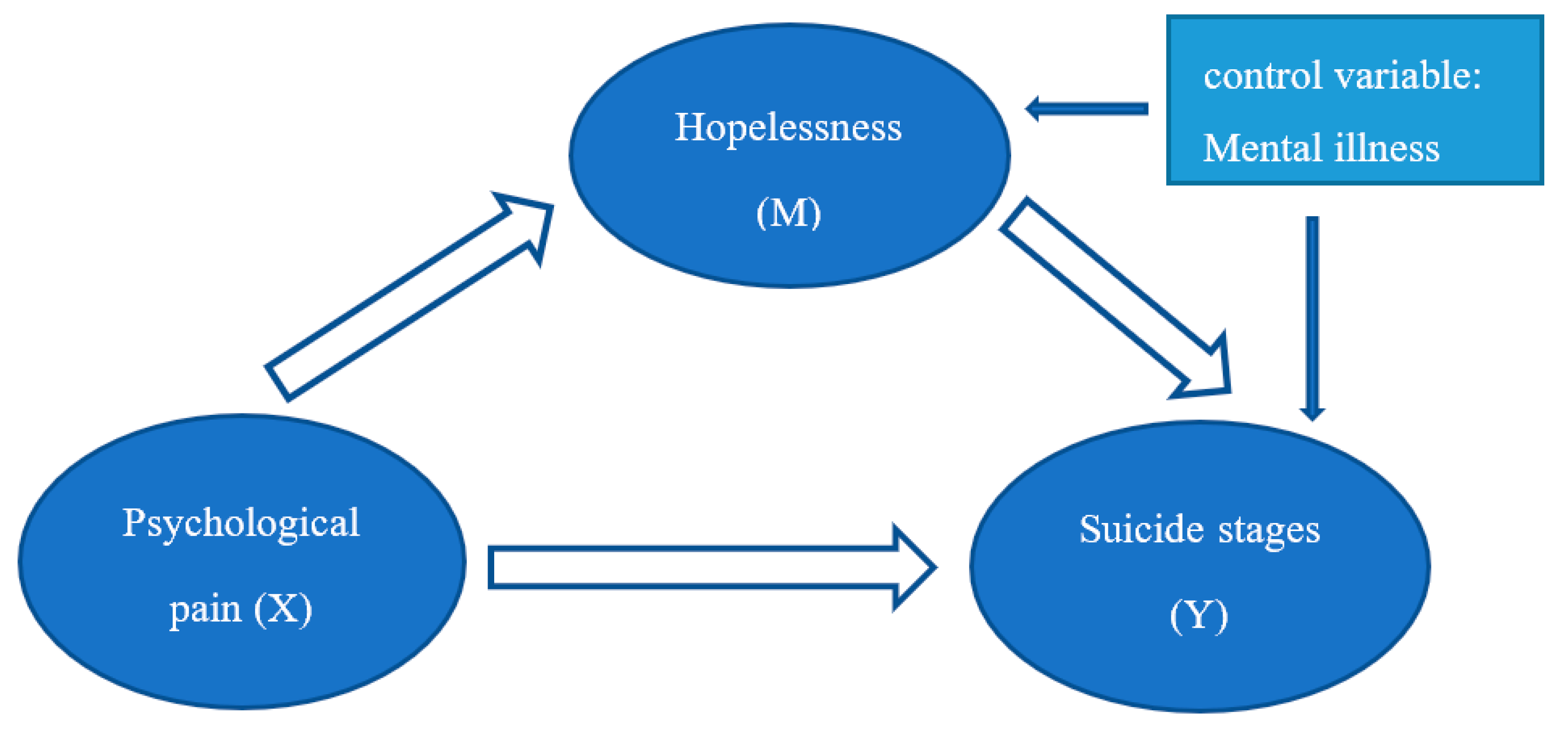

2.4.2. Analysis of Suicide Path

3. Results

3.1. Group Characteristics Reflected by Qualitative Analysis

3.2. Path Analysis of Psychological Pain, Hopelessness and Suicide Stages

4. Discussion

4.1. The Qualitative Analysis Results

4.2. The Mediating Effect of Hopelessness

4.3. The Hopelessness Expressions and the Suicide Stages

5. Limitations and Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Suicide [Fact sheet]. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs398/en/ (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Wang, C.W.; Chan, C.L.; Yip, P.S. Suicide rates in China from 2002 to 2011: An update. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weibo Development Report. Available online: https://data.weibo.com/report/reportDetail?id=456&sudaref=cn.bing.com (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Bridge, J.A.; Goldstein, T.R.; Brent, D.A. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2006, 47, 372–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursztein, C.; Apter, A. Adolescent suicide. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2009, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlow, S.J.; Rosenberg, J.; Moore, J.D.; Haas, A.P.; Koestner, B.; Hendin, H.; Nemeroff, C.B. Depression, desperation, and suicidal ideation in college students: Results from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention College Screening Project at Emory University. Depress. Anxiety 2008, 25, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korczak, D.J.; Finkelstein, Y.; Barwick, M.; Chaim, G.; Cleverley, K.; Henderson, J.; Monga, S.; Moretti, M.E.; Willan, A.; Szatmari, P. A suicide prevention strategy for youth presenting to the emergency department with suicide related behaviour: Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonker, J.E.; Schnabelrauch, C.A.; Dehaan, L.G. The relationship between spirituality and religiosity on psychological outcomes in adolescents and emerging adults: A meta-analytic review. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, L.Y.; Alloy, L.B.; Hogan, M.E.; Whitehouse, W.G.; Gibb, B.E.; Hankin, B.L.; Cornette, M.M. The Hopelessness Theory of Suicidality. In Suicide Science: Expanding the Boundaries; Joiner, T., Rudd, M.D., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Conejero, I.; Olié, E.; Calati, R.; Ducasse, D.; Courtet, P. Psychological Pain, Depression, and Suicide: Recent Evidences and Future Directions. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2018, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Fu, R.; Zou, Y.; Cui, Y. Predictive Roles of Three-Dimensional Psychological Pain, Psychache, and Depression in Suicidal Ideation among Chinese College Students. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, A.M.; Klonsky, E.D. Assessing motivations for suicide attempts: Development and psychometric properties of the inventory of motivations for suicide attempts. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2013, 43, 532–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneidman, E.S. Suicide as psychache. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1993, 181, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneidman, E.S. Perspectives on suicidology. Further reflections on suicide and psychache. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 1998, 28, 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Pompili, M.; Lester, D.; Leenaars, A.A.; Tatarelli, R.; Girardi, P. Psychache and suicide: A preliminary investigation. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2008, 38, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verrocchio, M.C.; Carrozzino, D.; Marchetti, D.; Andreasson, K.; Fulcheri, M.; Bech, P. Mental Pain and Suicide: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducasse, D.; Holden, R.R.; Boyer, L.; Artéro, S.; Calati, R.; Guillaume, S.; Courtet, P.; Olié, E. Psychological Pain in Suicidality: A Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2018, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xie, W.; Luo, X.; Fu, R.; Shi, C.; Ying, X.; Wang, N.; Yin, Q.; Wang, X. Clarifying the role of psychological pain in the risks of suicidal ideation and suicidal acts among patients with major depressive episodes. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2014, 44, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, E.D.; May, A. The Three-Step Theory (3ST): A New Theory of Suicide Rooted in the “Ideation-to-Action” Framework. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2015, 8, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazdin, A.E.; Rodgers, A.; Colbus, D. The hopelessness scale for children: Psychometric characteristics and concurrent validity. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 54, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Kovacs, M.; Garrison, B. Hopelessness and eventual suicide: A 10-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation. Am. J. Psychiatry 1985, 142, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Brown, G.K.; Steer, R.A. Prediction of eventual suicide in psychiatric inpatients by clinical ratings of hopelessness. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1989, 57, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, K.L.; Nakonezny, P.A.; Owen, V.J.; Rial, K.V.; Moorehead, A.P.; Kennard, B.D.; Emslie, G.J. Hopelessness as a Predictor of Suicide Ideation in Depressed Male and Female Adolescent Youth. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyaga, S.; Landén, M.; Boman, M.; Hultman, C.M.; Långström, N.; Lichtenstein, P. Mental illness, suicide and creativity: 40-year prospective total population study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Barona, E.; Guerrero-Molina, M.; Chambel, M.J.; Moreno-Manso, J.M.; Bueso-Izquierdo, N.; Barbosa-Torres, C. Suicidal Ideation and Mental Health: The Moderating Effect of Coping Strategies in the Police Force. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z. Psychological Factors Prediction and Application of Social Network Users; University of Jinan: Jinan, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, M.; Li, A.; Liu, T.; Zhu, T. Creating a Chinese suicide dictionary for identifying suicide risk on social media. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemkau, P.V. A Study in Manic-Depressive Psychosis. Am. J. Public Health Nations Health 1954, 44, 268–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, V.; Sainsbury, P. Suicide in London: An Ecological Study. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A (Gen.) 1956, 119, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenault-Lapierre, G.; Kim, C.; Turecki, G. Psychiatric diagnoses in 3275 suicides: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2004, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randall, J.R.; Walld, R.; Finlayson, G.; Sareen, J.; Martens, P.J.; Bolton, J.M. Acute risk of suicide and suicide attempts associated with recent diagnosis of mental disorders: A population-based, propensity score-matched analysis. Can. J. Psychiatry Rev. Can. Psychiatr. 2014, 59, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Xu, H.; Xie, S.; Chen, Q.; Jiang, L. A survey and analysis of suicidal ideation, suicide plan and suicide attempts in Dalian. Sichuan Ment. Health 2014, 3, 218–220. [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky, E.D.; May, A.M. Differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators: A critical frontier for suicidology research. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2014, 44, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Borges, G.; Bromet, E.J.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Beautrais, A.L.; Bruffaerts, R.; Chiu, W.T.; de Girolamo, G.; Gluzman, S.F.; et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br. J. Psychiatry 2008, 192, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charpentier, C.; Neve, J.-E.; Li, X.; Roiser, J.; Sharot, T. Models of Affective Decision Making: How Do Feelings Predict Choice? Psychol. Sci. 2016, 27, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharot, T.; Sunstein, C.R. How people decide what they want to know. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, B.W.; Hom, M.A.; Karnick, A.T.; Charpentier, C.J.; Keefer, L.A.; Capron, D.W.; Rudd, M.D.; Bryan, C.J. Does Hopelessness Accurately Predict How Bad You Will Feel in the Future? Initial Evidence of Affective Forecasting Errors in Individuals with Elevated Suicide Risk. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2022, 46, 686–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yihong, G.; Ling, M. Analysis of Suicidal Tendencies in Microblog Discourse: The Case of “Zoufan”. Foreign Lang. Teach. 2019, 1, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Ringel, E. The presuicidal syndrome. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 1976, 6, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.; Rodrigues, M.; Fisher, S.; Bailey, E.; Herrman, H. Social media and suicide prevention: Findings from a stakeholder survey. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, S.; Robinson, J.; Bendall, S.; Hetrick, S.; Cox, G.; Bailey, E.; Gleeson, J.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M. Online and Social Media Suicide Prevention Interventions for Young People: A Focus on Implementation and Moderation. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 25, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kokkevi, A.; Rotsika, V.; Arapaki, A.; Richardson, C. Adolescents’ self-reported suicide attempts, self-harm thoughts and their correlates across 17 European countries. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2012, 53, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swahn, M.H.; Bossarte, R.M.; Choquet, M.; Hassler, C.; Falissard, B.; Chau, N. Early substance use initiation and suicide ideation and attempts among students in France and the United States. Int. J. Public Health 2012, 57, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canetto, S.S.; Sakinofsky, I. The gender paradox in suicide. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 1998, 28, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, C.I.; Cotton, S.M.; Badcock, P.B.; Hetrick, S.E.; Berk, M.; Dean, O.M.; Chanen, A.M.; Davey, C.G. Relationships between Different Dimensions of Social Support and Suicidal Ideation in Young People with Major Depressive Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 281, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, D.; Wang, S.; Zhao, T.; Zang, Y.; Su, Y. Limitation on activities of daily living, depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among nursing home residents: The moderating role of resilience. Geriatr. Nurs. 2020, 41, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher Rabon, J.; Sirois, F.; Barton, A.; Hirsch, J. Self-compassion and suicidal behavior: Indirect effects of depression, anxiety, and hopelessness across increasingly vulnerable samples. Self Identity 2021, 21, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Definition | Number of words | Representative words |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide ideation | Words reflecting suicidal thoughts | 586 | want to die (想死) escape (逃离) |

| Suicide behavior | Words reflecting self-harm behaviors | 88 | jump down (跳楼) hang(吊死) |

| Psychological pain | Words reflecting psychological distress | 403 | want to cry (想哭) loneliness (孤单) |

| Mental illness | Words reflecting poor mental health status | 48 | depression (抑郁) hallucination (幻觉) |

| Hopelessness | Words reflecting a feeling of despair | 188 | dead end (死胡同) despair (绝望) |

| Somatic complaints | Words reflecting somatic symptoms | 183 | headache (头疼) shortness of breath (透不过气) |

| Self-regulation | Words reflecting an attempt to push oneself hard | 36 | repression (压抑) force oneself to smile (强颜欢笑) |

| Personality | Words reflecting negative personality | 72 | inferiority complex (自卑) hate oneself (讨厌自己) |

| Stress | Words reflecting pressure in daily life | 83 | failure (输) pressure (压力) |

| Trauma/hurt | Words reflecting traumatic or unpleasant experiences | 182 | get dumped (失恋) infidelity (出轨) |

| Talk about others | Words reflecting one’s relatives and friends | 47 | partner (妻子) son (儿子) |

| Shame/guilt | Words reflecting a feeling of shame and guilt | 72 | lose status (丢脸) making an apology (赔罪) |

| Anger/hostility | Words reflecting a feeling of being angry and hostile against others | 180 | damn it (他妈的) curse (诅咒) |

| Depression Mood | Suicide Ideation | Suicide Plan | Suicide Attempt |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) |

| 57 (54.3%) | 21 (20.0%) | 19 (18.1%) | 8 (7.6%) |

| RMSEA (<0.08) | CFI (>0.9) | TLI (>0.9) |

| 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Path | Total Effect (c) | X-M (a) | M-Y (b) | Direct Effects (c’) |

| Psychological pain → hopelessness → suicide stages | −0.154 * | 0.571 *** | −0.271 * | 0.052 |

| Mental illness → hopelessness | 0.006 | |||

| Mental illness → suicide stages | 0.398 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mo, L.; Li, H.; Zhu, T. Exploring the Suicide Mechanism Path of High-Suicide-Risk Adolescents—Based on Weibo Text Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811495

Mo L, Li H, Zhu T. Exploring the Suicide Mechanism Path of High-Suicide-Risk Adolescents—Based on Weibo Text Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811495

Chicago/Turabian StyleMo, Liuling, He Li, and Tingshao Zhu. 2022. "Exploring the Suicide Mechanism Path of High-Suicide-Risk Adolescents—Based on Weibo Text Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811495

APA StyleMo, L., Li, H., & Zhu, T. (2022). Exploring the Suicide Mechanism Path of High-Suicide-Risk Adolescents—Based on Weibo Text Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811495