Voluntary Carbon Disclosure (VCD) Strategy under the Korean ETS: With the Interaction among Carbon Performance, Foreign Sales Ratio and Media Visibility

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Carbon Performance and Voluntary Carbon Disclosure (VCD)

2.1.1. Two Competing Theories

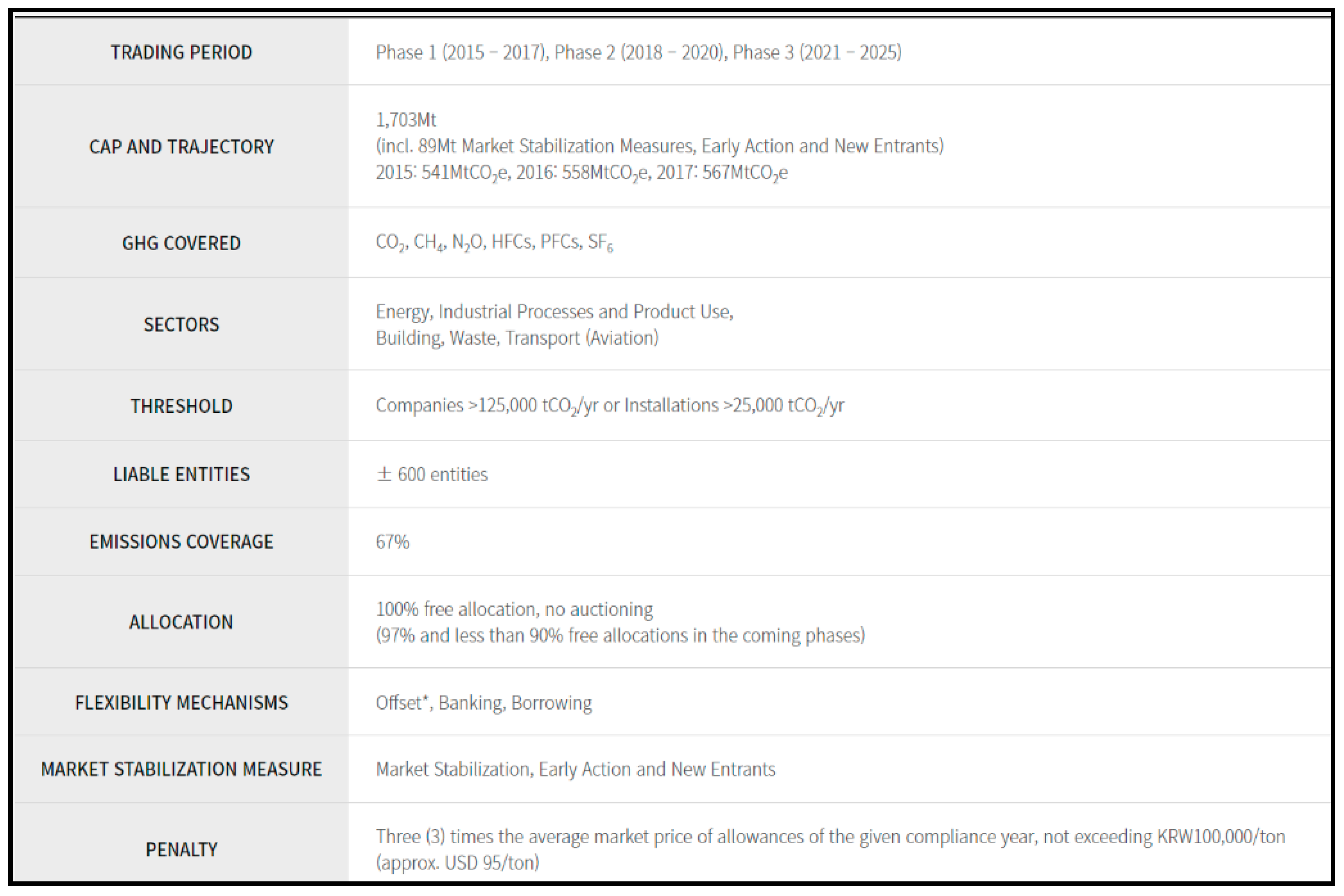

2.1.2. Nexus between ETS and VCD

2.1.3. Complementary Theory

2.2. Carbon Disclosure Strategy: How Internal Factors Interact with External Factors

2.2.1. Foreign Sales Ratio, Carbon Performance and Disclosure

2.2.2. Media Visibility, Carbon Performance, and Disclosure

3. Research Design and Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection

3.2. Data Measures

3.2.1. Voluntary Carbon Disclosure

3.2.2. Carbon Performance

3.2.3. Foreign Sales Ratio

3.2.4. Media Visibility

3.2.5. Control Variables

4. Result and Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Regression Analysis

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Sectors | Years | n | Mean | SD | Min | Median | Max | t-Test Diff. (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer discretionary | 2015 | 6 | 16.7 | 3.54 | 10 | 17 | 22 | 0.021 |

| 2016 | 5 | 18.4 | 2.06 | 16 | 18 | 22 | (0.984) | |

| 2017 | 6 | 16.5 | 4.31 | 8 | 17 | 22 | ||

| 2018 | 6 | 16.8 | 3.34 | 11 | 17 | 21 | ||

| 2019 | 7 | 16.7 | 3.88 | 11 | 19 | 21 | ||

| Consumer staples | 2015 | 2 | 12.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 12.5 | 15 | −0.465 |

| 2016 | 3 | 11.67 | 2.05 | 9 | 12 | 14 | (0.688) | |

| 2017 | 4 | 11.75 | 3.19 | 7 | 12 | 16 | ||

| 2018 | 4 | 11.75 | 2.95 | 7 | 12.5 | 15 | ||

| 2019 | 2 | 10.5 | 3.5 | 7 | 10.5 | 14 | ||

| Energy | 2015 | 4 | 9.75 | 1.3 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 3.617 |

| 2016 | 4 | 14 | 2.92 | 12 | 12.5 | 19 | (0.009) | |

| 2017 | 4 | 14.25 | 2.86 | 12 | 13 | 19 | ||

| 2018 | 5 | 15 | 2.45 | 12 | 14 | 19 | ||

| 2019 | 5 | 15.4 | 2.5 | 13 | 14 | 20 | ||

| Finance | 2015 | 4 | 13.25 | 2.77 | 11 | 12 | 18 | 2.064 |

| 2016 | 4 | 14.5 | 2.29 | 12 | 14 | 18 | (0.078) | |

| 2017 | 3 | 14.67 | 3.3 | 11 | 14 | 19 | ||

| 2018 | 5 | 16.6 | 4.41 | 12 | 15 | 25 | ||

| 2019 | 5 | 19 | 4.24 | 14 | 17 | 25 | ||

| Health care | 2015 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 1.391 |

| 2016 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 11 | (0.258) | |

| 2017 | 3 | 10.67 | 0.47 | 10 | 11 | 11 | ||

| 2018 | 3 | 11.67 | 0.94 | 11 | 11 | 16 | ||

| 2019 | 3 | 15.33 | 0.94 | 14 | 16 | 16 | ||

| Industrials | 2015 | 19 | 15.05 | 4.32 | 8 | 16 | 23 | 0.501 |

| 2016 | 23 | 14.43 | 4.37 | 6 | 14 | 26 | (0.619) | |

| 2017 | 26 | 13.65 | 4.57 | 7 | 13 | 28 | ||

| 2018 | 26 | 14 | 3.42 | 7 | 14 | 24 | ||

| 2019 | 26 | 15.69 | 3.99 | 9 | 15.5 | 27 | ||

| IT | 2015 | 10 | 15.8 | 5.19 | 7 | 15.5 | 26 | −0.118 |

| 2016 | 11 | 15 | 6.78 | 4 | 15 | 29 | (0.907) | |

| 2017 | 12 | 14.92 | 6.54 | 6 | 14 | 30 | ||

| 2018 | 12 | 15.08 | 6.3 | 6 | 14 | 29 | ||

| 2019 | 12 | 15.5 | 5.99 | 8 | 15 | 29 | ||

| Materials | 2015 | 17 | 16.06 | 4.26 | 8 | 15 | 29 | −0.439 |

| 2016 | 20 | 15.4 | 4.52 | 7 | 15.5 | 29 | (0.663) | |

| 2017 | 23 | 14.43 | 5 | 5 | 15 | 30 | ||

| 2018 | 23 | 15.35 | 5.26 | 7 | 15 | 33 | ||

| 2019 | 23 | 15.39 | 4.89 | 6 | 16 | 30 | ||

| Telecommunications | 2015 | 2 | 18.5 | 2.5 | 16 | 18.5 | 21 | −0.066 |

| 2016 | 2 | 18 | 1 | 17 | 18 | 19 | (0.952) | |

| 2017 | 3 | 17.69 | 1.89 | 15 | 19 | 19 | ||

| 2018 | 3 | 16.67 | 2.36 | 15 | 15 | 20 | ||

| 2019 | 3 | 18.33 | 1.89 | 17 | 17 | 21 |

| Categories | (%) 2015 | (%) 2016 | (%) 2017 | (%) 2018 | (%) 2019 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Change risks and opportunities | CC1 | assessment of risks and opportunities | 60% | 70% | 83% | 84% | 85% |

| CC2 | financial implications | 24% | 27% | 32% | 34% | 38% | |

| GHG emissions | GHG1 | methodology for calculation | 23% | 26% | 26% | 29% | 33% |

| GHG2 | external verification | 24% | 24% | 27% | 31% | 39% | |

| GHG3 | total emissions | 70% | 79% | 90% | 93% | 91% | |

| GHG4 | disclosure by scope | 64% | 73% | 84% | 86% | 86% | |

| GHG5 | disclosure by source | 14% | 15% | 14% | 15% | 16% | |

| GHG6 | disclosure by facility or segment | 31% | 32% | 34% | 33% | 31% | |

| GHG7 | historical comparison of emissions | 68% | 76% | 85% | 89% | 88% | |

| Energy consumption | EC1 | total consumed | 68% | 77% | 86% | 88% | 88% |

| EC2 | disclosure consumption from renewable source | 13% | 14% | 15% | 24% | 30% | |

| EC3 | disclosure by type, facility or segment | 52% | 59% | 65% | 67% | 66% | |

| GHG reduction and cost | RC1 | plans to reduce GHG emissions | 55% | 61% | 70% | 76% | 76% |

| RC2 | targets for GHG emissions | 32% | 38% | 38% | 44% | 53% | |

| RC3 | reductions achieved to date | 41% | 46% | 44% | 48% | 52% | |

| RC4 | costs of future emissions factored in capital expenditure planning | 2% | 4% | 2% | 4% | 2% | |

| GHG emission accountability | ACC1 | explanation of where responsibility lies for climate change policy and action 48% | 53% | 61% | 63% | 62% | |

| ACC2 | mechanism by which Board reviews company progress on climate change actions 26% | 30% | 31% | 30% | 35% | ||

References

- Pinkse, J.; Kolk, A. Business and Climate Change: Key Challenges in the Face of Policy Uncertainty and Economic Recession, Management Online Review. 2009. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1433037 (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Ward, A. Big Investors to Put More Money into Tackling Climate Change. Financial Times, 12 September 2017. Available online: https://www.ft.com(accessed on 3 September 2021).

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tuwaijri, S.; Christensen, T.; Hughes, I. The relations among environmental disclosure, environmental performance, and economic performance: A simultaneous equations approach. Account. Organ. Soc. 2004, 29, 447–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, V.N. Determinants of Carbon Accounting and Carbon Disclosure Practices: An Exploratory Study on Firms Affected under Emission Trading Schemes. Ph.D. Thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Comyns, B. Determinants of GHG Reporting: An Analysis of Global Oil and Gas companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 136, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Khan, T.; Siriwardhane, P. Sustainable development carbon pricing initiative and voluntary environmental disclosures quality. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1072–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depoers, F. Gouvernance et qualité de l’information sur les gaz à effet de serre publiée par les sociétés cotées. Comptab. Contrôle Audit 2010, 16, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L. The influence of institutional contexts on the relationship between voluntary carbon disclosure and carbon emission performance. Account. Finance 2019, 59, 1235–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Guidry, R.P.; Patten, D.M. Do actions speak louder than words? An empirical investigation of corporate environmental reputation. Account. Organ. Soc. 2012, 37, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, M.; Jaggi, B. Global warming and corporate disclosures: A comparative analysis of companies from the European Union, Japan and Canada. Sustain. Environ. Perform. Discl. 2010, 40, 129–160. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, M.; Jaggi, B. Carbon dioxide emissions and disclosures by electric utilities. Adv. Public Interest Account. 2004, 10, 105–129. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, C.H.; Patten, D.M. The role of environmental disclosures as tools of legitimacy: A research note. Account. Organ. Soc. 2007, 32, 630–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Account. Organ. Soc. 2008, 33, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, L. Opening up the firm: What explains participation and effort in voluntary carbon disclosure by global businesses? An analysis of internal firm factors and dynamics. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1302–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrazi, B.; de Villiers, C.; van Staden, C.J. The environmental disclosures of the electricity generation industry: A global perspective. Account. Bus. Res. 2016, 46, 665–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, S.; Deegan, C. Corporate disclosure reactions to Australia’s first national emission reporting scheme. Account. Finance 2011, 51, 409–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, C.; Fraas, J.W. Coming clean: The impact of environmental performance and visibility on corporate climate change disclosure. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.H.; Zeng, S.X.; Shi, J.J.; Qi, G.Y.; Zhang, Z.B. The relationship between corporate environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical study in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 145, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C. Introduction: The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures-A theoretical foundation. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O. Sustainability reports as simulacra? A counter-account of A and A+ GRI reports. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2013, 26, 1036–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Walmsley, A.; Cogotti, S.; McCombes, L.; Häusler, N. Corporate social responsibility: The disclosure–performance gap. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1544–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, C.; Fraas, J.W. Erratum to: Beyond acclamations and excuses: Environmental performance, voluntary environmental disclosure and the role of visibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 99, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, A.; Mackey, T.B.; Barney, J.B. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Performance: Investor Preferences and Corporate Strategies. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependency Perspective; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- State and Trends Carbon Pricing 2020, World Bank. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/33809 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Lee, S.Y.; Ahn, Y.H. Climate-entrepreneurship in response to climate change: Lessons from the Korean emissions trading scheme (ETS). Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2018, 11, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECOEYE. 2021. Available online: http://www.ecoeye-int.com/m21.php (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Kolk, A.; Levy, D.; Pinkse, J. Corporate responses in an emerging climate regime: The institutionalization and commensuration of carbon disclosure. Eur. Account. Rev. 2008, 17, 719–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Abhayawansa, S.; Jubb, C.; Perera, L. Regulatory impact on voluntary climate change–related reporting by Australian government owned corporations. Financ. Account. Manag. 2017, 33, 264–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, A. Corporate social responsibility reporting in professional accounting firms. Br. Account. Rev. 2016, 48, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, M.; Windsor, C.; Wahyuni, D. An investigation of voluntary corporate greenhouse gas emissions reporting in a market governance system: Australian evidence. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2011, 24, 1037–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Organizations: Rational, Natural and Open Systems, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H. The social construction of reputation: Certification contests, legitimation, and the survival of organizations in the American automobile industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 15, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, W.; Moon, J. Corporate social responsibility in Asia: A seven country study of CSR website reporting. Bus. Soc. 2005, 44, 415–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, T.E. Voluntary corporate disclosure by Swedish companies. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 1989, 1, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Li, H. Corporate social responsibility communication of Chinese and global corporations in China. Public Relat. Rev. 2009, 35, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, S.W.G.; Single, L.E.; Zarzeski, M.T. Nonfinancial disclosures across Anglo-American countries. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2001, 10, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanny, E. Voluntary Disclosures of Emissions by US Firms. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanny, E.; Ely, K. Corporate environmental disclosures about the effects of climate change. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Roth, K. Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 717–736. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, W.W.; DiMaggio, P.J. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, B.; Lee, D.; Psaros, J. An analysis of Australian company carbon emission disclosures. Pac. Account. Rev. 2013, 25, 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X. Determinants and features of voluntary disclosure in the Chinese stock market. China J. Account. Res. 2013, 6, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutantoputra, A.W.; Lindorff, M.; Jonson, E.W.P. The relationship between environmental performance and environmental disclosure. Aust. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Does it really pay to be green? Determinants and consequences of proactive environmental strategies. J. Account. Public Policy 2011, 30, 122–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiousis, S. Explicating Media Salience: A Factor Analysis of New York Times Issue Coverage During the 2000 U.S. Presidential Election. J. Commun. 2004, 54, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromiley, P. Corporate Capital Investment: A Behavioral Approach; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, E.; Toffel, M.W. Responding to Public and Private Politics: Corporate Disclosure of Climate Change Strategies. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 1157–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Gordon, I. An examination of social and environmental reporting strategies. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2001, 14, 587–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemma, T.T.; Feedman, M.; Mlilo, M.; Park, J.D. Corporate carbon risk, voluntary disclosure, and cost of capital: South African evidence. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, J.; Najah, M.M. Institutional investors influence on global climate change disclosure practices. Aust. J. Manag. 2012, 37, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Schaltegger, S. Revisiting carbon disclosure and performance: Legitimacy and management views. Br. Account. Rev. 2017, 49, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddock-Fraser, J.; Fraser, I. Assessing corporate environmental reporting motivations: Differences between ‘close-to market’ and ‘business-to-business’ companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meznar, M.B.; Johnson, J.H., Jr.; Mizzi, P.J. No News is Good News? Press Coverage and Corporate Public Affairs Management. J. Public Aff. 2006, 6, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartick, S.L.; Mahon, J.F. Toward a Substantive Definition of the Corporate Issue Construct. Bus. Soc. 1994, 33, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hypothesis | Description |

|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1 (H1) | Carbon performance will not be associated with voluntary carbon disclosure under the Korean ETS. |

| Hypothesis 2 (H2) | Foreign sales ratio will be positively associated with voluntary carbon disclosure. |

| Hypothesis 3 (H3) | Foreign sales will moderate the relationship between carbon performance and voluntary carbon disclosure such that companies will be more likely to provide disclosure (improve the quality of disclosure) when foreign sales is higher. |

| Hypothesis 4 (H4) | Media visibility will be positively associated with voluntary carbon disclosure. |

| Hypothesis 5 (H5) | Media visibility will moderate the relationship between carbon performance and voluntary carbon disclosure such that companies will be more likely to provide disclosure (improve the quality of disclosure) when media visibility is higher. |

| Categories | Items | |

|---|---|---|

| 1.Climate Change risks and opportunities | CC1 | assessment/description of the risks (regulatory, physical or general) relating to climate change and actions taken or to be taken to manage the risks |

| CC2 | assessment/description of current (and future) financial implications, business implications and opportunities of climate change | |

| 2. GHG emissions | GHG1 | description of the methodology used to calculate GHG emissions (e.g., GHG protocol or ISO) |

| GHG2 | existence external verification of quantity of GHG emission—if so by whom and on what basis | |

| GHG3 | total GHG emissions—metric tonnes CO-e emitted | |

| GHG4 | disclosure of Scopes 1 and 2, or Scope 3 direct GHG emissions | |

| GHG5 | disclosure of GHG emissions by source (e.g., coal, electricity, etc.) | |

| GHG6 | disclosure of GHG emissions by facility or segment level | |

| GHG7 | comparison of GHG emissions with previous years | |

| 3. Energy consumption | EC1 | total energy consumed (e.g., tera-joules or peta-joules) |

| EC2 | quantification of energy used from renewable source | |

| EC3 | disclosure by type, facility or segment | |

| 4. GHG reduction and cost | RC1 | detail plans or strategies to reduce GHG emissions |

| RC2 | specification of GHG emissions reduction target level and target year | |

| RC3 | emission reductions and associated costs or savings achieved to date as a result of the reduction plan | |

| RC4 | costs of future emissions factored into capital expenditure planning | |

| 5. GHG emission accountability | ACC1 | indication of which board committee (or other executive body) has overall responsibility for actions related to climate change |

| ACC2 | description of mechanism by which the board (or other executive body) reviews the company’s progress regarding climate change actions | |

| Descriptive Stats | Carbon Emission Intensity | Disclosure score |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.48865 | 14.974 |

| Std.dev. | 1.52388 | 4.668 |

| Min | 0.002 | 4 |

| Q1 | 0.02211 | 12 |

| Median | 0.06231 | 15 |

| Q3 | 0.24877 | 17 |

| Max | 11.076 | 33 |

| Sample Number | 421 | 397 |

| Variables | Mean | Std.dev. | Min | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEILog | −2.6511 | 1.86311 | −6.11 | −3.805 | −2.775 | −1.385 | 2.11 |

| Disclosure quality | 1.0154 | 0.30458 | 0.27 | 0.8421 | 1 | 1.1429 | 2.2 |

| Foreign sales | 0.3916 | 0.28009 | 0.0003 | 0.12 | 0.36 | 0.61 | 0.95 |

| Media Visibility | 155.842 | 254.35565 | 0 | 21 | 69.5 | 180.25 | 1450 |

| Size | 15.564 | 1.5573 | 12.08 | 14.58 | 15.49 | 16.5025 | 19.88 |

| Leverage | 0.491 | 0.20825 | 0.03253 | 0.35562 | 0.5063 | 0.6164 | 0.93928 |

| CapEX | 2.2365 | 3.3538 | 0.039 | 0.91 | 1.25 | 1.84 | 18.79 |

| ROE | 5.8247 | 30.6914 | −1251.9 | 0.9775 | 5.95 | 10.1125 | 210.85 |

| EMI | 1,977,710 | 6,827,176 | 5980 | 54,471 | 157,533 | 802,266 | 59,573,482 |

| N = 343 | |||||||

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. VCD_qual | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Size | 0.386 *** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Lev | −0.169 ** | 0.035 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 4. CapEX | 0.161 ** | 0.359 *** | 0.077 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 5. ROE | 0.020 | −0.036 | −0.031 | 0.123 * | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 6. EMI | 0.373 *** | 0.250 *** | −0.252 *** | −0.063 | −0.008 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 7. CDPper | 0.211 *** | 0.342 *** | −0.167 ** | 0.047 | −0.012 | 0.109 * | 1 | ||||||||||

| 8. IND Group1 | −0.021 | −0.324 *** | −0.009 | −0.194 *** | −0.203 *** | 0.115 * | −0.027 | 1 | |||||||||

| 9. IND Group2 | −0.095 * | −0.060 | −0.096 * | −0.115 * | 0.041 | −0.1 * | 0.052 | −0.542 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| 10. IND Group3 | 0.093 * | 0.168 ** | −0.156 ** | −0.118 * | 0.043 | −0.009 | 0.010 | −0.588 *** | −0.149 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 11. Y2015 | −0.025 | 0.037 | 0.050 | 0.011 | −0.013 | 0.018 | 0.024 | −0.020 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 1 | ||||||

| 12. Y2016 | 0.039 | 0.034 | 0.011 | 0.026 | −0.011 | 0.008 | 0.044 | 0.009 | 0.000 | −0.025 | −0.207 *** | 1 | |||||

| 13. Y2017 | 0.001 | −0.047 | −0.038 | −0.01 | 0.011 | −0.010 | −0.027 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.008 | −0.231 *** | −0.244 *** | 1 | ||||

| 14. Y2018 | 0.013 | −0.033 | −0.004 | −0.032 | 0.009 | −0.012 | −0.034 | −0.001 | 0.007 | −0.001 | −0.237 *** | −0.251 *** | −0.279 *** | 1 | |||

| 15. CEILog(CP) | 0.016 | −0.225 *** | −0.279 *** | −0.039 | 0.017 | 0.454 *** | 0.033 | 0.294 *** | −0.218 *** | −0.009 | 0.026 | 0.019 | 0.016 | −0.020 | 1 | ||

| 16. F_sales | 0.255 *** | 0.113 * | −0.277 *** | −0.269 *** | −0.058 | 0.053 | 0.208 *** | 0.083 | −0.141 | 0.258 *** | −0.008 | −0.017 | −0.025 | 0.006 | 0.152 ** | 1 | |

| 17. M_visi | 0.324 *** | 0.503 *** | −0.124 * | −0.042 * | −0.001 | 0.116 * | 0.208 *** | −0.398 *** | 0.185 *** | 0.375 *** | 0.031 | 0.018 | −0.021 | −0.024 | −0.119 * | 0.197 *** | 1 |

| Variables | Dependent Variable: VCD_qual | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| [Model 1] | [Model 2] | [Model 3] | |

| Coeff. t-Value | Coeff. t-Value | Coeff. t-Value | |

| CEILog | −0.203 ** (−3.249) | −0.273 ***(−4.362) | −0.171 * (−2.273) |

| F_sales | 0.229 *** (4.135) | 0.218 *** (3.978) | |

| CEILog * F_sales | −0.129 * (−2.419) | −0.114 * (−2.111) | |

| M_Visi | 0.245 *** (3.594) | ||

| CEILog * M_visi | 0.156 * (2.281) | ||

| Size | 0.304 *** (4.279) | 0.216 ** (2.994) | 0.128 (1.540) |

| Leverage | −0.005 (−0.089) | 0.024 (0.416) | 0.019 (0.346) |

| CapEx | 0.341 *** (4.496) | 0.377 *** (5.097) | 0.395 *** (5.427) |

| ROE | 0.114 * (2.161) | 0.067 (1.275) | 0.057 (1.094) |

| Emission Amount | 0.365 *** (5.972) | 0.420 *** (6.972) | 0.321 *** (4.270) |

| CDPper | 0.051 (0.957) | 0.029 (0.567) | 0.049 (0.962) |

| Industry: | |||

| IND Group 1 | 0.818 *** (4.382) | 0.549 ** (2.903) | 0.468 * (2.487) |

| IND Group 2 | 0.483 ** (3.494) | 0.343 * (2.502) | 0.261 (1.867) |

| IND Group 3 | 0.631 *** (4.403) | 0.420 ** (2.893) | 0.299 * (2.021) |

| Year: | |||

| Y2015 | −0.011 (−0.188) | 0.004 (0.065) | 0.004 (0.081) |

| Y2016 | 0.048 (0.836) | 0.066 (1.176) | 0.059 (1.084) |

| Y2017 | 0.036 (0.612) | 0.062 (1.081) | 0.065 (1.158) |

| Y2018 | 0.052 (0.879) | 0.066 (1.151) | 0.067 (1.192) |

| Constant | −0.672 * (−2.262) | −0.381 (−1.298) | −0.024 (−0.074) |

| adju R² | 0.317 | 0.367 | 0.394 |

| F-static | 10.232 *** | 11.074 *** | 10.980 *** |

| N | 343 | 343 | 343 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.A.; Kim, J.D. Voluntary Carbon Disclosure (VCD) Strategy under the Korean ETS: With the Interaction among Carbon Performance, Foreign Sales Ratio and Media Visibility. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811268

Kim SA, Kim JD. Voluntary Carbon Disclosure (VCD) Strategy under the Korean ETS: With the Interaction among Carbon Performance, Foreign Sales Ratio and Media Visibility. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811268

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Sun Ae, and Jong Dae Kim. 2022. "Voluntary Carbon Disclosure (VCD) Strategy under the Korean ETS: With the Interaction among Carbon Performance, Foreign Sales Ratio and Media Visibility" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811268

APA StyleKim, S. A., & Kim, J. D. (2022). Voluntary Carbon Disclosure (VCD) Strategy under the Korean ETS: With the Interaction among Carbon Performance, Foreign Sales Ratio and Media Visibility. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811268