The Perception of the Patient Safety Climate by Health Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic—International Research

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

- What attitudes toward factors related to hospitalized patient safety are presented by nurses, physicians and paramedics?

- What were the differences in attitudes toward safety in the study groups?

- To what extent did the place of residence differentiate the attitudes toward safety of nurses, physicians, and paramedics?

- What was the relationship between the time of employment of the respondents and their attitudes toward safety?

2.2. Characteristics of the Research Tool

2.3. Data Collection, Setting and Procedure

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the People Participating in the Study

3.2. Results of Safety Attitude Questionnaire (SAQ-SF) in Research Group

3.3. Correlation and Multiple Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

- Participant perceptions about the patient safety climate were not at a particularly satisfactory level, and there is still a need for the development of patient safety culture in healthcare in Europe.

- The results are valuable to identify areas for improvement related to patient safety. Positive working conditions, effective teamwork and better perception of management can contribute to improving employee attitudes toward patient safety.

- Healthcare leaders should take into account more suggestions from their workers to improve the safety climate in the workplace.

- This study was carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic and should be repeated after its completion, and comparative studies will allow for a more precise determination of the safety climate in the assessment of employees.

7. Implications for Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malinowska-Lipień, I.; Micek, A.; Gabryś, T.; Kózka, M.; Gajda, K.; Gniadek, A.; Brzostek, T.; Squires, A. Nurses and physicians attitudes towards factors related to hospitalized patient safety. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrani, A.; Hoxha, A.; Simaku, A.; Gabrani, J.C. Application of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ) in Albanian hospitals: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gabrani, J.C.; Knibb, W.; Petrela, E.; Hoxha, A.; Gabrani, A. Provider Perspectives on Safety in Primary Care in Albania. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2016, 48, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzer, J.K.; Meterko, M.; Singer, S.J. The patient safety climate in healthcare organizations (PSCHO) survey: Short-form development. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2017, 23, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrente, G.; Barbosa, S.F.F. Questionnaire for assessing patient safety culture in emergency services: An integrative review. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2021, 74, e20190693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azyabi, A.; Karwowski, W.; Davahli, M.R. Assessing Patient Safety Culture in Hospital Settings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Scott, L.D.; Dahinten, V.S.; Vincent, C.; Lopez, K.D.; Park, C.G. Safety Culture, Patient Safety, and Quality of Care Outcomes: A Literature Review. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2017, 41, 279–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, S.J.; Vogus, T.J. Reducing hospital errors: Interventions that build safety culture. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2013, 34, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Profit, J.; Etchegaray, J.; Petersen, L.A.; Sexton, J.B.; Hysong, S.J.; Mei, M.; Thomas, E.J. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire as a tool for benchmarking safety culture in the NICU. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012, 97, F127–F132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Xi, X.; Zhang, J.; Feng, J.; Deng, X.; Li, A.; Zhou, J. The safety attitudes questionnaire in Chinese: Psychometric properties and benchmarking data of the safety culture in Beijing hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sexton, J.B.; Helmreich, R.L.; Neilands, T.B.; Rowan, R.; Vella, K.; Boyden, J.; Roberts, P.R.; Thomas, E.J. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: Psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2006, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Statistica 13. Available online: http://statistica.io (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Turkmen, E.; Baykal, U.; Intepeler, S.S.; Altuntas, S. Nurses’ perceptions of and factors promoting patient safety culture in Turkey. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2013, 28, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalçın Akgül, G.; Aksoy, N. The Relationship Between Organizational Stress Levels and Patient Safety Attitudes in Operating Room Staff. J. Perianesth. Nurs. 2021, 36, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozer, S.; Sarsilmaz Kankaya, H.; Aktas Toptas, H.; Aykar, F.S. Attitudes Toward Patient Safety and Tendencies to Medical Error Among Turkish Cardiology and Cardiovascular Surgery Nurses. J. Patient Saf. 2019, 15, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, S.; Önler, E. Turkish surgical nurses’ attitudes related to patient safety: A questionnaire study. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2020, 23, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünver, S.; Yeniğün, S.C. Patient Safety Attitude of Nurses Working in Surgical Units: A Cross-Sectional Study in Turkey. J. PeriAnesth. Nurs. 2020, 35, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aletras, V.H.; Kallianidou, K. Performance obstacles of nurses in intensive care units of Greek National Health System hospitals. Nurs. Crit. Care 2016, 21, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raftopoulos, V.; Pavlakis, A. Safety climate in 5 intensive care units: A nationwide hospital survey using the Greek-Cypriot version of the safety attitudes questionnaire. J. Crit. Care 2013, 28, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, S.; Hammer, A.; Bartels, P.; Suñol, R.; Groene, O.; Thompson, C.A.; Arah, O.A.; Kutaj-Wasikowska, H.; Michel, P.; Wagner, C. Quality management and perceptions of teamwork and safety climate in European hospitals. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2015, 27, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Tian, L.; Yan, C.; Li, Y.; Fang, H.; Peihang, S.; Li, P.; Jia, H.; Wang, Y.; Kang, Z.; et al. A cross-sectional survey on patient safety culture in secondary hospitals of Northeast China. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, N.; Jones, R.; Abdel-Latif, M.E. Attitudes of Doctors and Nurses toward Patient Safety within Emergency Departments of a Saudi Arabian Hospital: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2019, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schwendimann, R.; Zimmermann, N.; Küng, K.; Ausserhofer, D.; Sexton, B. Variation in safety culture dimensions within and between US and Swiss Hospital Units: An exploratory study. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2013, 22, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, C.J.; Cooper, S.; Endacott, R. Measuring the safety climate in an Australian emergency department. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2021, 58, 101048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tondo, J.C.A.; Guirardello, E.B. Perception of nursing professionals on patient safety culture. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2017, 70, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milton, J.; Chaboyer, W.; Åberg, N.D.; Erichsen Andersson, A.; Oxelmark, L. Safety attitudes and working climate after organizational change in a major emergency department in Sweden. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2020, 53, 100830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondevik, G.T.; Hofoss, D.; Husebø, B.S.; Deilkås, E.C.T. Patient safety culture in Norwegian nursing homes. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, E.; Porter, J.E.; Morphet, J. An exploration of emergency nurses’ perceptions, attitudes and experience of teamwork in the emergency department. Australas. Emerg. Nurs. J. 2017, 20, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Källberg, A.S.; Ehrenberg, A.; Florin, J.; Östergren, J.; Göransson, K.E. Physicians’ and nurses’ perceptions of patient safety risks in the emergency department. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2017, 33, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigobello, M.C.G.; Carvalho, R.E.F.L.; Guerreiro, J.M.; Motta, A.P.G.; Atila, E.; Gimenes, F.R.E. The perception of the patient safety climate by professionals of the emergency department. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2017, 33, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, N.; Jones, R.; Rizwan, A.; Abdel-Latif, M.E. Safety attitudes in hospital emergency departments: A systematic review. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2019, 32, 1042–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female Male | 828 233 | 78 22 |

| Age (years) | Under 26 26 to 35 years 36 to 45 years 46 to 55 years 56 years or older | 149 357 352 110 93 | 14 34 33 10 9 |

| Position | Nurse Paramedic Physicians | 561 253 247 | 53 24 23 |

| Years in specialty | Less than 6 months 6–11 months 1 to 2 yrs 3 to 4 yrs 5–10 yrs 11 or more | 141 127 208 267 190 128 | 13 12 20 25 18 12 |

| Country | France Greece Poland Spain Turkey | 230 116 125 332 258 | 20 19 19 20 22 |

| % Neutral | % Disagree | % Agree | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teamwork Climate | |||||

| 1. Nurse input is well received in this clinical area | 0.8% | 7.8% | 91.4% | 4.75 | 0.82 |

| 2. In this clinical area, it is difficult to speak up if I perceive a problem with patient care | 0.0% | 10.9% | 89.1% | 4.64 | 1.05 |

| 3. Disagreements in this clinical area are resolved appropriately (i.e., not who is right, but what is best for the patient) | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 1.88 | 0.33 |

| 4. I have the support I need from other personnel to care for patients | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 5.00 | |

| 5. It is easy for personnel here to ask questions when there is something that they do not understand | 17.3% | 15.0% | 67.7% | 3.53 | 0.74 |

| 6. The physicians and nurses here work together as a well-coordinated team | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 1.75 | 0.43 |

| Safety Climate | |||||

| 7. I would feel safe being treated here as a patient | 0.0% | 10.2% | 89.8% | 4.59 | 1.21 |

| 8. Medical errors are handled appropriately in this clinical area | 0.0% | 5.7% | 94.3% | 4.77 | 0.93 |

| 9. I know the proper channels to direct questions regarding patient safety in this clinical area | 13.3% | 5.2% | 81.5% | 4.57 | 0.93 |

| 10. I receive appropriate feedback about my performance | 17.7% | 0.0% | 82.3% | 4.65 | 0.76 |

| 11. In this clinical area, it is difficult to discuss errors | 0.0% | 92.2% | 7.8% | 1.31 | 1.07 |

| 12. I am encouraged by my colleagues to report any patient safety concerns I may have | 11.0% | 5.1% | 83.9% | 4.62 | 0.89 |

| 13. The culture in this clinical area makes it easy to learn from the errors of others | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 1.77 | 0.42 |

| Job Satisfaction | |||||

| 14. My suggestions about safety would be acted upon if I expressed them to management | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 1.46 | 0.50 |

| 15. I like my job. | 13.2% | 2.8% | 84.0% | 4.65 | 0.82 |

| 16. Working here is like being part of a large family | 20.5% | 0.0% | 79.5% | 4.59 | 0.81 |

| 17. This is a good place to work | 17.2% | 0.0% | 79.5% | 4.66 | 0.76 |

| 18. I am proud to work in this clinical area | 50.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 4.00 | 1.00 |

| Stress Recognition | |||||

| 19. Morale in this clinical area is high | 22.0% | 0.0% | 78.0% | 4.56 | 0.83 |

| 20. When my workload becomes excessive, my performance is impaired | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 5.00 | |

| 21. I am less effective at work when fatigued | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 5.00 | |

| 22. I am more likely to make errors in tense or hostile situations | 15.3% | 0.0% | 84.7% | 4.69 | 0.72 |

| Perceptions of Management | |||||

| 23. Fatigue impairs my performance during emergency situations (e.g., emergency resuscitation, seizure) | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 5.00 | |

| 24. Management supports my daily efforts at unit | 46.0% | 20.9% | 33.1% | 3.24 | 1.45 |

| 25. Management does not knowingly compromise pt safety at unit | 33.6% | 50.0% | 16.5% | 2.33 | 1.49 |

| 26. Management is doing a good job in the unit | 33.5% | 49.5% | 17.1% | 2.35 | 1.50 |

| 27. Problem personnel are dealt with constructively by our unit | 28.8% | 57.0% | 14.1% | 2.14 | 1.45 |

| 28. I get adequate, timely info about events that might affect my work from the unit | 31.8% | 0.0% | 68.2% | 4.36 | 0.93 |

| 29. Management supports my daily efforts at hospital | 31.1% | 50.2% | 18.7% | 2.37 | 1.54 |

| 30. Management does not knowingly compromise pt safety at the hospital | 71.1% | 14.6% | 14.3% | 2.99 | 1.08 |

| 31. Management is doing a good job at the hospital | 39.6% | 0.0% | 60.4% | 4.21 | 0.98 |

| 32. Problem personnel are dealt with constructively at our hospital | 30.8% | 52.4% | 16.8% | 2.29 | 1.50 |

| 33. I get adequate, timely info about events that might affect my work from the hospital | 23.6% | 9.8% | 66.6% | 4.14 | 1.33 |

| Working Conditions | |||||

| 34. The levels of staffing in this clinical area are sufficient to handle the number of patients | 30.6% | 47.6% | 21.8% | 2.48 | 1.58 |

| 35. This hospital does a good job of training new personnel | 37.7% | 43.5% | 18.8% | 2.50 | 1.50 |

| 36. All the necessary information for diagnostic and therapeutic decisions is routinely available to me | 29.2% | 0.0% | 70.8% | 4.42 | 0.91 |

| Position | Teamwork Climate (TC) | Safety Climate (SC) | Job Satisfaction (JS) | Stress Recognition (SR) | Perceptions of Management (PM) | Working Conditions (WC) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Women | 51.64 | 4.27 | 80.74 | 7.46 | 86.70 | 9.41 | 97.77 | 4.79 | 50.65 | 10.95 | 48.72 | 16.50 |

| Men | 49.27 | 4.85 | 81.58 | 9.54 | 89.31 | 8.57 | 99.25 | 2.98 | 52.58 | 10.31 | 47.00 | 10.90 |

| Total | 51.12 | 4.51 | 80.92 | 7.97 | 87.28 | 9.29 | 98.09 | 4.50 | 51.07 | 10.84 | 48.34 | 15.45 |

| p | M < F *** | F < M *** | F < M *** | F < M ** | ||||||||

| Professional group | ||||||||||||

| Nurse-A | 51.57 | 4.05 | 79.40 | 8.15 | 87.67 | 9.82 | 98.77 | 3.72 | 53.31 | 11.50 | 47.19 | 15.83 |

| Paramedic-B | 50.69 | 4.63 | 83.26 | 6.54 | 84.90 | 8.47 | 96.39 | 5.67 | 46.44 | 7.61 | 54.15 | 15.75 |

| Physician-C | 50.51 | 5.24 | 81.98 | 8.15 | 88.81 | 8.39 | 98.28 | 4.32 | 50.73 | 10.59 | 44.99 | 12.48 |

| Total | 51.12 | 4.51 | 80.92 | 7.97 | 87.28 | 9.29 | 98.09 | 4.50 | 51.07 | 10.84 | 48.34 | 15.45 |

| p | A > B, C ** | A < B, C *** | B < A, C *** | B < A, C *** | B < A, C ***, C < A ** | B > A, C *** | ||||||

| Seniority | ||||||||||||

| less than 6 months A | 50.89 | 6.12 | 84.80 | 5.60 | 90.57 | 7.25 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 50.11 | 10.80 | 48.76 | 18.92 |

| 6–11 month B | 51.08 | 4.70 | 83.86 | 7.03 | 90.24 | 9.15 | 99.41 | 2.66 | 49.33 | 11.62 | 47.64 | 13.34 |

| 1 to 2 yrs C | 51.20 | 3.60 | 77.20 | 9.65 | 85.63 | 8.59 | 97.00 | 5.35 | 51.90 | 10.55 | 46.81 | 16.92 |

| 3 to 4 yrs D | 51.26 | 5.32 | 82.12 | 5.88 | 85.62 | 9.21 | 97.47 | 5.03 | 51.78 | 11.43 | 51.12 | 12.11 |

| 5–10 yrs E | 50.86 | 3.55 | 79.30 | 8.53 | 88.32 | 8.61 | 98.03 | 4.57 | 52.63 | 9.96 | 45.20 | 14.57 |

| 11 or more F | 51.33 | 2.66 | 79.69 | 7.55 | 85.31 | 11.62 | 97.85 | 4.73 | 48.71 | 9.99 | 49.90 | 17.15 |

| Total | 51.12 | 4.51 | 80.92 | 7.97 | 87.28 | 9.29 | 98.09 | 4.50 | 51.07 | 10.84 | 48.34 | 15.45 |

| p | A > C, D, E, F B > C, D, E C < D, E, F D > E, F | A > C, D, F, A > E B > C, D, F C < E, D > E E < F | A > C, D, E, F B > C, D, E C < E D > E, F | A > E B < C, D, E C < F D < F E < F | A > E B < D C < D D < E E > F | |||||||

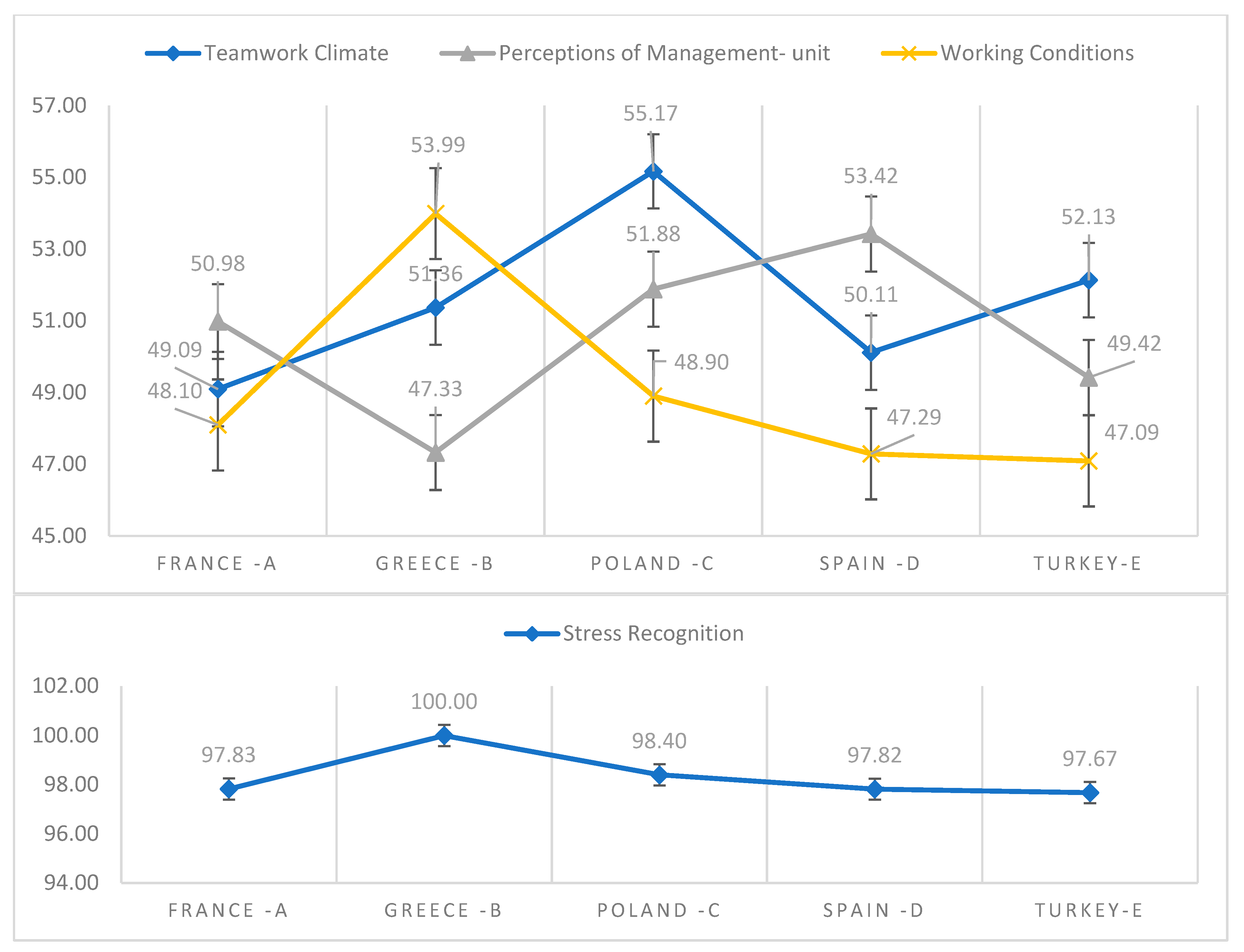

| Country | ||||||||||||

| France-A | 49.09 | 4.17 | 80.22 | 7.59 | 86.83 | 9.14 | 97.83 | 4.75 | 50.98 | 11.57 | 48.10 | 12.52 |

| Greece-B | 51.36 | 3.19 | 80.73 | 5.59 | 87.50 | 6.93 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 47.33 | 9.77 | 53.99 | 16.78 |

| Poland-C | 55.17 | 5.85 | 81.60 | 8.53 | 88.40 | 8.99 | 98.40 | 4.19 | 51.88 | 11.35 | 48.90 | 17.25 |

| Spain-D | 50.11 | 4.18 | 81.36 | 7.73 | 87.21 | 9.85 | 97.82 | 4.75 | 53.42 | 9.01 | 47.29 | 14.22 |

| Turkey-E | 52.13 | 3.29 | 80.74 | 9.13 | 87.11 | 9.77 | 97.67 | 4.87 | 49.42 | 11.80 | 47.09 | 17.26 |

| Total | 51.12 | 4.51 | 80.92 | 7.97 | 87.28 | 9.29 | 98.09 | 4.50 | 51.07 | 10.84 | 48.34 | 15.45 |

| p | A < B, C, D, E ***, B < C, B > D C > D < E D < E | B > A, D, E B > C | B < A, C, D A < D | B > A, D, E B > C | ||||||||

| SAQ | Nurse-A (N = 561) | Paramedic-B (N = 253) | Physician-C (N = 247) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | n | % | n | % | n | % | p | |

| Teamwork Climate | <75 | 561 | 100% | 253 | 100% | 247 | 98% | |

| ≥75 | ||||||||

| Safety Climate | <75 | 120 | 21.39% | 15 | 5.93% | 32 | 12.65% | 0.000001 |

| ≥75 | 441 | 78.61% | 238 | 94.07% | 215 | 84.98% | ||

| Job Satisfaction | <75 | 60 | 10.70% | 24 | 9.49% | 10 | 3.95% | 0.004 |

| ≥75 | 501 | 89.30% | 229 | 90.51% | 237 | 93.68% | ||

| Stress Recognition | <75 | |||||||

| ≥75 | 561 | 100% | 253 | 100.00% | 247 | 97.63% | ||

| Perceptions of Management | <75 | 549 | 0.000001 | 253 | 100.00% | 247 | 97.63% | 0.0005 |

| ≥75 | 12 | 2.14% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | ||

| Working Conditions | <75 | 527 | 93.94% | 212 | 83.79% | 241 | 95.26% | |

| ≥75 | 34 | 6.06% | 41 | 16.21% | 6 | 2.37% | ||

| SAQ | France-A (N = 230) | Greece-B (N = 116) | Poland-C (N = 125) | Spain-D (N = 332) | Turkey-E (N = 258) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | p | |

| Teamwork Climate | <75 | 230 | 100% | 116 | 100% | 125 | 100% | 332 | 100% | 258 | 100% | |

| ≥75 | ||||||||||||

| Safety Climate | <75 | 40 | 17.39% | 8 | 6.90% | 24 | 19.20% | 47 | 14.16% | 48 | 18.60% | 0.02 |

| ≥75 | 190 | 82.61% | 108 | 93.10% | 101 | 80.80% | 285 | 85.84% | 210 | 81.40% | ||

| Job Satisfaction | <75 | 15 | 6.52% | 5 | 4.31% | 5 | 4.00% | 43 | 12.95% | 26 | 10.08% | 0.003 |

| ≥75 | 215 | 93.48% | 111 | 95.69% | 120 | 96.00% | 289 | 87.05% | 232 | 89.92% | ||

| Stress Recognition | <75 | |||||||||||

| ≥75 | 230 | 100.00% | 116 | 100.00% | 125 | 100.00% | 332 | 100.00% | 258 | 100.00% | ||

| Perceptions of Management | <75 | 230 | 100.00% | 116 | 100.00% | 119 | 95.20% | 332 | 100.00% | 252 | 97.67% | 0.00003 |

| ≥75 | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 6 | 4.80% | 0 | 0.00% | 6 | 2.33% | ||

| Working Conditions | <75 | 230 | 100.00% | 85 | 73.28% | 113 | 90.40% | 318 | 95.78% | 234 | 90.70% | 0.000001 |

| ≥75 | 0 | 0.00% | 31 | 26.72% | 12 | 9.60% | 14 | 4.22% | 24 | 9.30% | ||

| SAQ | M | SD | K | A | Teamwork Climate | Safety Climate | Job Satisfaction | Stress Recognition | Perceptions of Management | Working Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teamwork Climate | 51.12 | 4.51 | 0.0 | 1.3 | ||||||

| Safety Climate | 80.92 | 7.97 | −0.8 | 0.0 | 0.03 | |||||

| Job Satisfaction | 87.28 | 9.29 | −0.4 | −0.3 | 0.02 | 0.04 | ||||

| Stress Recognition | 98.09 | 4.50 | −1.4 | 1.4 | −0.01 | 0.10 | 0.27 | |||

| Perceptions of Management | 51.07 | 10.84 | −0.1 | −0.8 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.02 | −0.01 | ||

| Working Conditions | 48.34 | 15.45 | 0.0 | −0.6 | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.25 | 0.02 | −0.06 |

| Multiple R-Spearman | Multiple R Square [%] | R Square Change | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teamwork Climate | R2 = 0.19, p < 0.000 | |||

| Poland | 0.328 | 11% | 11% | 0.000 |

| Turkey | 0.385 | 15% | 4% | 0.000 |

| France | 0.401 | 16% | 1% | 0.000 |

| 5–10 yrs | 0.415 | 17% | 1% | 0.000 |

| 11 or more | 0.426 | 18% | 1% | 0.001 |

| Spain | 0.437 | 19% | 1% | 0.000 |

| Safety Climate | R2 = 0.15, p < 0.000 | |||

| 1 to 2 yrs | 0.231 | 5% | 5% | 0.000 |

| Nurse | 0.301 | 9% | 4% | 0.000 |

| less than 6 months | 0.344 | 12% | 3% | 0.000 |

| 6–11 month | 0.367 | 13% | 2% | 0.000 |

| 3 to 4 yrs | 0.388 | 15% | 2% | 0.000 |

| Physician | 0.393 | 15% | 0% | 0.025 |

| Job Satisfaction | R2 = 0.07, p < 0.000 | |||

| Paramedic | 0.143 | 2% | 2% | 0.000 |

| less than 6 months | 0.204 | 4% | 2% | 0.000 |

| 6–11 month | 0.237 | 6% | 1% | 0.000 |

| 5–10 yrs | 0.256 | 7% | 1% | 0.001 |

| Stress Recognition | R2 = 0.11, p < 0.000 | |||

| Paramedic | 0.211 | 4% | 4% | 0.000 |

| less than 6 months | 0.274 | 8% | 3% | 0.000 |

| Greece | 0.305 | 9% | 2% | 0.000 |

| 6–11 month | 0.322 | 10% | 1% | 0.000 |

| France | 0.330 | 11% | 1% | 0.013 |

| Perceptions of Management | R2 = 0.10, p < 0.000 | |||

| Paramedic | 0.239 | 6% | 6% | 0.000 |

| Spain | 0.277 | 8% | 2% | 0.000 |

| Greece | 0.297 | 9% | 1% | 0.000 |

| Physician | 0.314 | 10% | 1% | 0.000 |

| Working Conditions | R2 = 0.07, p < 0.000 | |||

| Paramedic | 0.211 | 4% | 4% | 0.000 |

| Greece | 0.254 | 6% | 2% | 0.000 |

| 3 to 4 yrs | 0.272 | 7% | 1% | 0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kosydar-Bochenek, J.; Krupa, S.; Religa, D.; Friganović, A.; Oomen, B.; Brioni, E.; Iordanou, S.; Suchoparski, M.; Knap, M.; Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W. The Perception of the Patient Safety Climate by Health Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic—International Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159712

Kosydar-Bochenek J, Krupa S, Religa D, Friganović A, Oomen B, Brioni E, Iordanou S, Suchoparski M, Knap M, Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska W. The Perception of the Patient Safety Climate by Health Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic—International Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159712

Chicago/Turabian StyleKosydar-Bochenek, Justyna, Sabina Krupa, Dorota Religa, Adriano Friganović, Ber Oomen, Elena Brioni, Stelios Iordanou, Marcin Suchoparski, Małgorzata Knap, and Wioletta Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska. 2022. "The Perception of the Patient Safety Climate by Health Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic—International Research" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 9712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159712

APA StyleKosydar-Bochenek, J., Krupa, S., Religa, D., Friganović, A., Oomen, B., Brioni, E., Iordanou, S., Suchoparski, M., Knap, M., & Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W. (2022). The Perception of the Patient Safety Climate by Health Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic—International Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159712