Re-Envisioning an Early Years System of Care towards Equity in Canada: A Critical, Rapid Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. An Intersectional Framing of Children’s Early Years

a way of understanding and analyzing the complexity in the world, in people, and in human experiences. The events and conditions of social and political life and the self can seldom be understood as shaped by one factor. They are generally shaped by many factors in diverse and mutually influencing ways. When it comes to social inequality, people’s lives and the organization of power in a given society are better understood as being shaped not by a single axis of social division, be it race or gender or class, but by many axes that work together and influence each other. Intersectionality as an analytical tool gives people better access to the complexity of the world and of themselves.[4]

3. Child Health Inequities in Canada

Structural Inequities and Violence

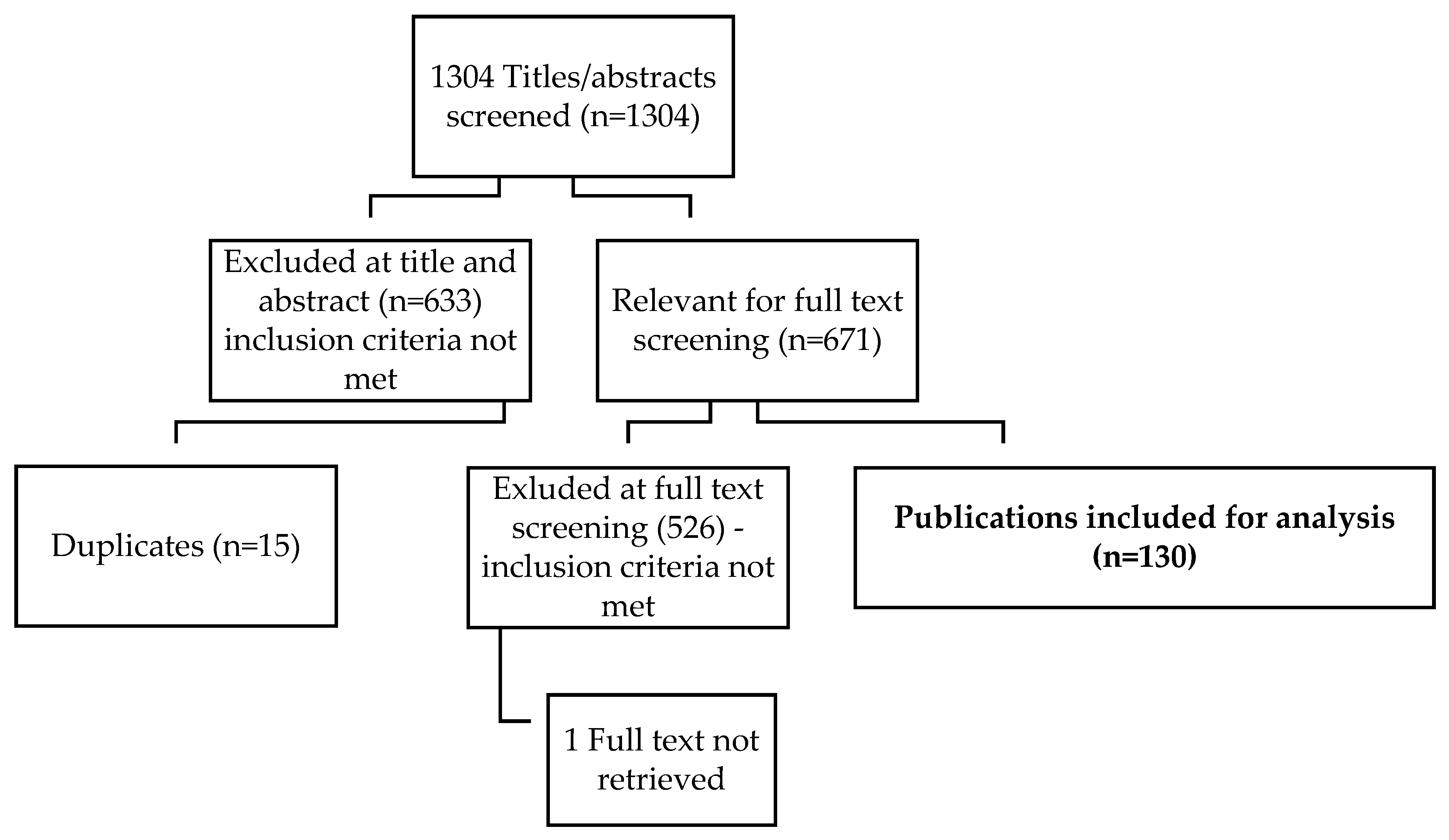

4. Methods

4.1. Step 1. Defining the Research Question

4.2. Step 2. Searching for Research Evidence

4.3. Step 3. Data Extraction

4.4. Step 4. Analyzing the Findings

5. Findings

5.1. Top-Down Political Leadership—Upstream Accountability and Macro-System Actions

5.2. A Comprehensive and Responsive System for Community, Family and Maternal Wellness

5.3. Coordinated and Funded Intersectoral Alliances and Actions

5.4. Embedding Equity in Data Collection and Accountability Systems

5.5. Bottom-Up Demand—Community Driven Co-Design and Tailoring

5.6. Relational Approaches

6. Discussion of Policy and Research Recommendations

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Slopen, N.; Williams, D.R. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the impacts of racism on the foundations of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, H.; Coll-Seck, A.; Banerjee, A.; Peterson, S.; Dalglish, S.L.; Ameratunga, S.; Balabonova, D. A future for the world’s children? A WHO-UNICEF-Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 395, 605–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shonkoff, J.P. Re-Envisioning Early Childhood Policy and Practice in a World of Striking Inequality and Uncertainty; Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hill Collins, P.; Bilge, S. Intersectionality; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, P.H. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, b. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, 2nd ed.; South End Press Classics: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K.W. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ. Chic. Leg. Forum 1989, 140, 138–167. [Google Scholar]

- Hankivsky, O.; de Leeuw, S.; Lee, J.-A.; Bilkis, V.; Khanlou, N. Health Inequities in Canada: Intersectional Frameworks and Practices; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Plamondon, K.; Caxaj, C.S.; Graham, I.D.; Botorff, J.L. Connecting knowledge with action for health equity: A critical interpretive synthesis of promising practices. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gerlach, A.J.; Teachman, G.; Laliberte Rudman, D.; Huot, S.; Aldrich, R. Expanding beyond individualism: Engaging critical perspectives on occupation. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 25, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlach, A.J.; Browne, A.J.; Greenwood, M. Engaging Indigenous families in a community-based early childhood program in British Columbia, Canada: A cultural safety perspective. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, S.; Greenwood, M. Beyond borders and boundaries: Addressing Indigenous health inequities in Canada through theories of social determinants of health and intersectionality. In Health Inequities in Canada: Intersectional Frameworks and Practices; Hankivsky, O., Ed.; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011; pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, A.; Erikson, S.L. How nurses come to race: Racialization in public health breastfeeding promotion. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 43, E11–E24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janus, M.; Reid-Westoby, C.; Raiter, N.; Forer, B.; Guhn, M. Population-level data on child development at school entry reflecting social determinants of health: A narrative review of studies using the early developmental instrument. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shramko, M.; Pfluger, L.; Harrison, B. Intersectionality and Trauma-Informed Applications for Maternal and Child Health Research and Evaluation: An Initial Summary of the Literature; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach, A.J.; Browne, A.J.; Suto, M.J. Relational approaches to fostering health equity for Indigenous children through early childhood intervention. Health Sociol. Rev. 2018, 27, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadan, Y.; Spilsbury, J.C.; Korbin, J.E. Culture and context in understanding child maltreatment: Contributions of intersectionality and neighborhood-based research. Child Abus. Negl. 2015, 41, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin Khan, M.; Kobayashi, K. No one should be left behind: Identifying appropriate health promotion practices for immigrants. In Health Promotion in Canada: New Perspectives On Theory, Practice, Policy, and Research, 4th ed.; Rootman, I., Pederson, A., Frohlich, K.L., Deupere, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017; pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health. Glossary of Essential Health Equity Terms; National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health: Antigonish, NS, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health. Let’s Talk Advocacy and Health Equity; National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health: Antigonish, NS, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael, D.; Bryant, T.; Mikkonen, J.; Raphael, A. Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts, 2nd ed.; Ontario Tech University Faculty of Health Sciences: Oshawa, ON, Canada; York University School of Health Policy and Management: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF Canada. Worlds Apart: Canadian Companion to UNCEF Report Card 16; UNICEF Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Health Promot. Int. 1991, 6, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, D. The health of Canada’s children. Part iii: Public policy and the social determinants of children’s health. Paediatr. Child Health 2010, 15, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gurstein, P.; Vilches, S. Re-envisioning the environment of support for lone mothers in extreme poverty. In Public Policy for Women: The State, Income Security, and Labour Market Issues; Griffin Cohen, M., Pulkingham, J., Eds.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011; pp. 226–247. [Google Scholar]

- Representative for Children and Youth. Not Fully Invested: A Follow-Up Report on the Representative’s Past Recommendations to Help Vulnerable Children in B.C. 2014. Available online: https://www.rcybc.ca/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/reports_publications/rcy-recreport2014-revisedfinal.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2014).

- Pan American Health Organization. Just Societies: Health Equity and Dignified Lives. Report of the Commission of the Pan American Health Organization on Equity and Health Inequalities in the Americas; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Representative for Children and Youth. Alone and Afraid: Lessons Learned from the Ordeal of a Child with Special Needs and His Family; Representative for Children and Youth: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock, C. Toward the full and proper implementation of Jordan’s Principle: An elusive goal to date. Paediatr. Child Health 2016, 21, 245–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dunn, J.R.; Dyck, I. Social determinants of health in Canada’s immigrant population: Results from the National Population Health Survey. Soc. Sci. Med. Med. Anthropol. 2000, 51, 1573–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Representative for Children and Youth & Office of the Provincial Health Officer. Growing Up in B.C. Available online: https://www.rcybc.ca/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/reports_publications/guibc-2015-finalforweb_0.pdf?utm_source=E-News+Contacts&utm_campaign=ac1527cea9-BCACCS+E-News+for+June+23%2C+2015&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_0bdd35ef3a-ac1527cea9-88221037 (accessed on 23 June 2015).

- Lamb, C.S. Constructing early childhood services as culturally credible trauma-recovery environments: Participatory barriers and enablers for refugee families. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2020, 28, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhas, R.S.; Graham, H.; Jegathesan, T.; Huber, J.; Young, E.; Barozzino, T. Supporting the developmental health of refugee children and youth. Paediatr. Child Health 2017, 22, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campaign 2000. 2021 Report Card on Child and Family Poverty in Canada. No One Left Behind: Strategies for An Inclusive Recovery; Campaign 2000: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Key Health Inequalities in Canada: A National Portrait; Public Health Agency of Canada: Nepean, ON, Canada, 2018.

- Loppie, C.; Wien, F. Understanding Indigenous Health Inequalities Through a Social Determinants Model. National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health: Prince George, BC, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Commission on Social Determinants of Health Final Report. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43943/1/9789241563703_eng.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2010).

- Plamondon, K.; Bottorff, J.L.; Caxaj, S.C.; Graham, I.D. The integration of evidence from the Commission on Social Determinants of Health in the field of health equity: A scoping review. Crit. Public Health 2018, 30, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Closing the Health Equity Gap: Policy Options and Opportunities for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, A.J.; Varcoe, C.; Ford-Gilboe, M. Equity-Oriented Primary Health Care Interventions for Marginalized Populations: Addressing Structural Inequities and Structural Violence; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, P.E.; Nizeye, B.; Stulac, S.; Keshavjee, S. Structural violence and clinical medicine. PLoS Med. 2007, 3, 1686–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanna, B.; Kleinman, A. Unpacking global health. In Reimagining Global Health: An Introduction; Farmer, P.E., Kim, Y.J., Kleinman, A., Basilico, M., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA; Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Galtung, J. Violence, peace and peace research. J. Peace Res. 1969, 6, 167–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone Blanchard, S.; Ryan Newton, J.; Didericksen, K.W.; Daniels, M.; Glosson, K. Confronting racism and bias within early intervention: The responsibility of systems and individuals to influence change and advance equity. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2021, 41, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health. Let’s Talk: Racism and Health Equity; National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health: Antigonish, NS, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, A.F. Whanau ora: A culturally-informed, social policy innovation. N. Z. Sociol. 2019, 34, 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, A.F.; Gifford, H.H. Whānau ora; he whakaaro Ā whānau: Māori family views of family wellbeing. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2014, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gee, G.C.; Walsemann, K.M.; Brondolo, E. A life course perspective on how racism may be related to health inequities. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braveman, P.; Barclay, C. Health disparities beginning in childhood: A life-course. Pediatrics 2009, 124 (Suppl 3), S163–S175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barlow, A.; Mullany, B.; Neault, N.; Compton, S.; Carter, A.; Hastings, R.; Billy, T.; Coho-Mescal, V.; Lorenzo, S.; Walkup, J. Effect of a paraprofessional home-visiting intervention on American Indian teen mothers’ and infants’ behavioral risks: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, R.; Bowes, J.; Elcombe, E. Child participation and family engagement with early childhood education and care services in disadvantaged Australian communities. Int. J. Early Child. 2014, 46, 271–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.; Jack, S.; Ballantyne, M.; Gabel, C.; Bomberry, R.; Wahoush, O. How Indigenous mothers experience selecting and using early childhood development services to care for their infants. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2019, 14, 1601486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKenzie, H.A.; Varcoe, C.; Browne, A.J.; Day, L. Disrupting the continuities among residential schools, the Sixties Scoop, and child welfare: An analysis of colonial and neocolonial discourses. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2016, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada; Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ganann, R.; Cilliska, D.; Thomas, H. Expediting systematic reviews: Methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hare, J.; Anderson, J. Transitions to early childhood education and care for indigenous children and families in Canada: Historical and social realities. Australas. J. Early Child. 2010, 35, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. Rapid Review Guidebook: STEPS for Conducting a Rapid Review; National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Antony, J.; Zarin, W.; Strifler, L.; Ghassemi, M.; Ivory, J.; Perrier, L.; Hutton, B.; Moher, D.; Straus, S.E. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gerlach, A.J.; Browne, A.J. Interrogating play as a strategy to foster child health equity and counteract racism and racialization. J. Occup. Sci. 2020, 28, 414–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, A.J.; McFadden, A. Orienting an Early Years System of Care Towards Equity: A Research Brief for the Office of the Representative of Children and Youth in British Columbia; University of Victoria: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, A.J.; Varcoe, C. Orienting child- and family-centred care towards equity. J. Child Health Care 2020, 25, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, A.J. Steps in the Right Direction: Connecting and Collaboration in Early Intervention Therapy with Aboriginal Families and Communities in British Columbia. 2007. Available online: http://www.acc-society.bc.ca/files_new/documents/StepsintheRightDirectionConnectingandCollaboratinginEarlyInterventionTherapywithAb.Familiesa.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Gerlach, A.J. Sharpening our critical edge: Occupational therapy in the context of ‘marginalized populations’ Canadian. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 82, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlach, A.J.; Browne, A.J.; Sinha, V.; Elliott, D. Navigating structural violence with Indigenous families: The contested terrain of early childhood intervention and the child welfare system in Canada. Int. Indige-Nous Policy J. 2017, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, R. Implications of inequities in health for health promotion practice. In Health Promotion in Canada: New Perspectives on Theory, Practice, Policy, and Research, 4th ed.; Rootman, I., Pederson, A., Frohlich, K.L., Deupere, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017; pp. 146–166. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, T.G.; Fry, R. Place-Based Approaches to Child and Family Services—A Literature Review; Murdoch Childrens Research Institute and The Royal Children’s Hospital Centre for Community Child Health: Parkville, Victoria, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, N.; Raman, S.; O’Hare, B.; Tamburlini, G. Addressing inequities in child health and development: Towards social justice. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2019, 3, e000503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, F.; Townsend, B.; Fisher, M.; Browne-Yung, K.; Freeman, T.; Ziersch, A.; Harris, P.; Friel, S. Creating political will for action on health equity: Practical lessons for public health policy actors. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2022, 11, 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archambault, J.; Côté, D.; Raynault, M. Early childhood education and care access for children from disadvantaged backgrounds: Using a framework to guide intervention. Early Child. Educ. J. 2020, 48, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mahon, R. Governable spaces of early childhood education and care: The Canadian case. In The Policies of Childcare and Early Childhood Education: Does Equal Access Matter? Repo, K., Alasuutari, M., Karita, K., Lammi-Taskula, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friendly, M. Early Childhood Education and Care in Canada 2016; Childcare Resource and Research Unit: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, M.; Jones, E. Being at the interface: Early childhood as a determinant of health. In Determinants of Indigenous Peoples’ Health in Canada: Beyond the Social; Greenwood, M., de Leeuw, S., Lindsay, N.M., Eds.; Canadian Scholars’ Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018; pp. 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, S.; Roe, Y.; Ireland, S.; Kildea, S.; Haora, P.; Gao, Y.; Maypilama, E.L.; Kruske, S.; Campbell, S.; Moore, S.; et al. A call for action that cannot go to voicemail: Research activism to urgently improve indigenous perinatal health and wellbeing. J. Aust. Coll. Midwives 2021, 34, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ineese-Nash, N.; Bomberry, Y.; Underwood, K.; Hache, A. Raising a child with early childhood dis-ability supports Shakonehya:ra’s ne shakoyen’okon:’a G’chi-gshkewesiwad binoonhyag ᑲᒥᓂᑯᓯᒼ ᑭᑫᑕᓱᐧᐃᓇ ᐊᐧᐊᔕᔥ ᑲᒥᓂᑯᓯᒼ ᑲᐧᐃᔕᑭᑫᑕᑲ: Ga-Miinigoowozid Gikendaagoosowin Awaazigish, Ga-Miinigoowozid Ga-Izhichigetan. Indig. Policy J. 2018, XXVIII. [Google Scholar]

- Halseth, R.; Greenwood, M. Indigenous Early Childhood Development in Canada: Current State of Knowledge and Future Directions; The National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health (NCCAH): Prince George, BC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada; Assembly of First Nations; Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami; Métis National Council. Indigenous early Learning and Child care Framework; Employment and Social Development Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018.

- United Nations. UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Available online: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2012).

- Parliament of Canada. An Act Respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis Children, Youth and Families, Revised Statutes of Canada (C-92); Parliament of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020.

- Pan American Health Organization. Advancing the Health in All Policies Approach in the Americas: What Is the Health Sector’s Role? A Brief Guide and Recommendations for Promoting Intersectoral Collaboration; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Greszczuk, C. Implementing Health in All Policies: Lessons from Around the World; Health Foundation: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tonelli, M.; Tang, K.; Forest, P. Canada needs a ‘health in all policies’ action plan now. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2020, 192, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wettergren, B.; Blennow, M.; Hiern, A.; Soder, O.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Child health systems in Sweden. J. Pediatr. 2016, 177, S187–S202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marmot, M. Achieving health equity: From root causes to fair outcomes, Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Lancet 2007, 370, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, A.J.; Jenkins, E.J.; Hodgson, K. Disrupting assumptions of risky play in the context of structural marginalization: A community engagement project in a Canadian inner-city neighbourhood. Health Place 2019, 55, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Nexus & Health Equity Council. Addressing Health Inequities for Racialized Communities: A Resource Guide; Health Nexus & Health Equity Council: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014.

- Early Intervention Foundation Adverse Childhood Experiences: What We Know, What We Don’t Know, and What Should Happen Next; Early Intervention Foundation: London, UK, 2020.

- Raphael, J.L. Pediatric health disparities and place-based strategies. In Disparities in Child Health: A Solutions-Based Approach; Lopez, M.A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ritte, R.; Panozza, S.; Johnston, L.; Agerholm, J.; Kvernmo, S.E.; Rowley, K.; Arabena, K. An Australian model of the First 1000 days: An Indigenous-led process to turn an international initiative into an early-life strategy benefiting Indigenous families. Glob. Health Epidemiol. Genom. 2016, 1, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gerlach, A.J.; Gignac, J. Continuities between family engagement and wellbeing in Aboriginal Head Start Programs in Canada: A qualitative inquiry. Infants Young Child. 2019, 32, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, M.; de Leeuw, S. Social determinants of health and the future wellbeing of Aboriginal children in Canada. Paediatr. Child Health 2012, 17, 381–384. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach, A.J.; Gulamhusein, S.; Varley, L.; Perron, M. Structural challenges and inequities in operating urban Indigenous early learning and child care programs in British Columbia. J. Child. Stud. 2021, 46, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J. Early childhood care and development programs as hook and hub for inter-sectoral service delivery in First Nations communities. J. Aborig. Health 2005, 1, 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam, J.; Scott, L.; Loock, C.; Wong, S. The RICHER social pediatrics model: Fostering access and reducing inequities in children’s health. Healthc. Q. 2011, 14, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loock, C.; Moore, E.; Vo, D.; Friesen, R.G.; Warf, C.; Lynam, J. Social pediatrics: A model to confront family poverty, adversity and housing instability and foster healthy child and adolescent development and resilience. In Clinical Care for Homeless, Runaway and Refugee Youth: Intervention Approaches, Education and Research Directions; Curren, W., Grant, C., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 117–141. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, I.; Lynam, J.; O’Campo, P.; Manson, H.; Lynch, M.; Dashti, B.; Turner, N.; Feller, A.; Ford-Jones, E.L.; Makin, S.; et al. It takes a village: A realist synthesis of social pediatrics program. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 64, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beck, A.F.; Anderson, K.L.; Rich, K.; Taylor, S.C.; Iyer, S.B.; Kotagal, U.R.; Kahn, R.S. Cooling the hot spots where child hospitalization rates are high: A neighborhood approach to population health. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meek, S.; Smith, L.T.; Allen, R.; Catherine, E.; Edyburn, K.; Williams, C.; Fabes, R.; McIntosh, K.; Garcia, E. Start with Equity: From the Early Years to the Early Grades: Data, Research and An Actionable Child Equity Policy Agenda; Arizona State University: Tempe, AZ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Leveraging the Best Available Evidence; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019.

- Knoche, L.L.; Witte, A.L. Home-School Partnerships in support of young children’s development: The intersection of relationships, rurality, and race. In African American Children in Early Childhood Education: Making the Case for Policy Investments in Families, Schools, and Communities; IIruka, U., Curenton, S.M., Durden, T.R., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bentley, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J. Improving School Transitions for Health Equity; IHE International: Oak Brook, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Early Intervention Foundation. Adverse Childhood Experiences: Building Consensus on What Should Happen Next; Early Intervention Foundation: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bhopti, A.; Brown, T.; Lentin, P. Family quality of life: A key outcome in early childhood intervention services—A scoping review. J. EarlyInterv. 2016, 4, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuna, N.; Summers, J.A.; Turnbull, A.P.; Hu, X.; Xu, S. Theorizing about family quality of life. In Enhancing the Quality of Life of People with Intellectual Disabilities; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 241–278. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, O.O.; Londoño Tobón, A.; Njoroge, W.F.M. Social determinants of health: The impact of racism on early childhood mental health. Child Adolesc. Disord. 2021, 23, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health. A Gaps Analysis to Improve Health Equity Knowledge and Practices; National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health: Antigonish, NS, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lewing, B.; Standford, M.; Redmond, T. Planning Early Childhood Services in 2020: Learning from Practice and Research on Children’s Centres and Family Hubs; Early Intervention Foundation: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach, A.J.; Gordon, J.; Elliott, D. Exploring the Influence of Organizational & Structural Factors on the Delivery of Early Intervention with Indigenous Families & Children in British Columbia; University of Victoria: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- VicHealth. Promoting Equity in Early Childhood Development for Health Equity through the Life Course; VicHealth: Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, M.; Larstone, R.; Lindsay, N.; Halseth, R.; Foster, P. Exploring the Data Landscapes of First Nations, Inuit, and Metis Children’s Early Learning and Childcare; National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health: Prince George, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McBride, D.; Widley, K. Family Hubs, Stockton-On-Tees: Early Childhood Services Case Example; Early Intervention Foundation: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, K.A. Toward population impact from early childhood psychological interventions. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 1117–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.G.; McDonald, M.; McHugh-Dillon, H. Early Childhood Development and The Social Determinants of Health Inequities: A Review of the Evidence. 2014. Available online: http://www.rch.org.au/uploadedFiles/Main/Content/ccch/151014_Evidence-review-early-childhood-development-and-the-social-determinants-of-health-inequities_Sept2015.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2015).

- Vargas-Baron, E. Early childhood policy planning and implementation: Community and provincial participation. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2019, 89, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Community Child Health. Policy Brief: Place-Based Approaches to Supporting Children and Families; Centre for Community Child Health: Parkville, Victoria, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, T.G.; McHugh-Dillon, H.; Bull, K.; Fry, R.; Laidlaw, B.; West, S. The Evidence: What We Know about Place-Based Approaches to Support Children’s Wellbeing. Collaborate for Children Scoping Project; The Royal Children’s Hospital: Melbourne, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach, A.J.; Gordon, J.; Elliott, D. Exploring Structural Constraints & Opportunities in A Hard-to-Reach System Using a Lens of Trauma- and Violence-Informed Care: Early Child Development & Intervention with Indigenous Families and Children in British Columbia; University of Victoria: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, C.; Morgan, C.; Holly, J. Counteracting dysconscious racism and abelism through fieldwork: Applying discrit classroom ecology in early childhood personnel preparation. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2021, 41, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, M.; Lindsay, N.; King, J.; Loewen, D. Ethical spaces and places: Indigenous cultural safety in British Columbia health care. AlterNative Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2017, 13, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.D.; Smith, S.; Bringewatt, E. Helping Young Children Who Have Experienced Trauma: Policies and Strategies for Early Care and Education; National Center for Children in Poverty, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, C.M.; Ndumbe-Eyoh, S.; Clement, C. Critical examination of knowledge to action models and implications for promoting health equity. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richter, L.M.; Daelmans, B.; Lombardi, J.; Heymann, J.; Boo, F.L.; Behrman, J.R.; Lu, C.; Lucas, J.E.; Perez-Escamilla, R.; Dua, T.; et al. Investing in the foundation of sustainable development: Pathways to scale up for early childhood development. Lancet 2017, 389, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dalglish, S.L. Future directions for reducing inequity and maximising impact of child health strategies. Br. Med. J. 2018, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whitley, J.; Beauchamp, M.H.; Browne, C. The impact of COVID-19 on the learning and achievement of vulnerable Canadian children and youth. FACETS 2021, 6, 1693–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inclusion BC. Kids Can’t Wait: The Case for Investing in Early Childhood Intervention Programs in British Columbia; Inclusion BC: New Westminster, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government of British Columbia. New Anti-Racism Data Act Will Help Fight Systemic Racism. 2022. Available online: https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2022PREM0027-000673 (accessed on 12 May 2021).

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Prenatal period Children aged 0–8 years (In the authors’ home province of BC, the early years is currently conceptualized from birth to 8 years of age) | The literature that exclusively focused on individuals over the age of 8 (e.g., youth, non-pregnant women) |

| Global Setting | High-income countries | Low- or middle-income countries |

| Research | Explicit equity focus Critical and intersectional framing of health in/equity Prenatal to age 8 years Written in English language Any study type | Lack of equity focus No evidence of critical or intersectional framing of health in/equity Children over 8 years of age Written in language other than English |

| Author(s) (Year) and Title | Location | Publication Type and Research Method(s) | Target Population | Findings | Elements of Equity Orientation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archambault, J., et al., (2020). Early childhood education and care access for children from disadvantaged backgrounds: Using a framework to guide intervention | Canada | Peer-reviewed publication reporting on literature synthesis | Children 0–5 years and families from “disadvantaged backgrounds” | Authors propose a framework identifying factors influencing access to quality early childhood education and care for children from “disadvantaged backgrounds”. | Multi-purpose and co-located; intersectoral and multisectoral partners and actions; integrated service; relational and responsive programming; government buy-in and support, neighborhood-level programs; outreach; family as partners; training support for staff. |

| Ball, J. (2005). Early childhood care and development programs as hook and hub for inter-sectoral service delivery in First Nations communities | Canada | Peer-reviewed publication reporting on multi-site, mixed methods study | First Nations families and young children | Author proposes a conceptual model of early childhood care and development programs as a hook for mobilizing community involvement in supporting young children and families and as a hub for meeting a range of service and social support needs of community members. | Co-location of child care with other services in multi-purpose, community-based service centres to improve access to health monitoring and care, screening for special services and early interventions. |

| Baum, F., et al., (2020). Creating political will for action on health equity: practical lessons for public health policy actors. | Australia | Peer-reviewed publication reporting on qualitative case study methodology | Policy stakeholders | Paper provides evidence of the factors that work for or against action to reduce health inequities by addressing the social determinants of health inequities. | Political framing of inequities away from a medical and behavioral framing and towards human right to health. |

| Beck, A. F., et al., (2019). Cooling the hot spots where child hospitalization rates are high: A neighborhood approach to population health | United States | Peer-reviewed publication on quality improvement initiative | Hospitalized children from lower-income families | Hospitalizations reduced by 20% through intersectoral action, multi-disciplinary teams, and community participation; and use of actionable, real-time data. | Intersectional action; community participation and tailoring; neighborhood level; data-driven action. |

| Berry, O. O., et al., (2021). Social determinants of health: The impact of racism on early childhood mental health | United States | Peer-reviewed publication synthesizing published literature and longitudinal studies | Racialized children ages 0–5 and their caregivers | Young children’s socio-emotional development is highly influenced by exposure to multiple and interconnecting levels of racism and discrimination. | Relational and anti-racist prevention and intervention strategies targeting young children and parents. |

| Boulton, A. F., et al., (2014). Whānau ora; he whakaaro Ā whānau: Māori family views of family wellbeing | Aotearoa New Zealand | Peer-reviewed publication reporting on qualitative study and policy analysis | Māori families | Whānau ora (family well-being) is a multidimensional concept that is time and context specific. Requires Māori self-determination, long-term relationships and financial investments. | Holistic, wrap-around, intersectoral services for whole family. A “one-size fits all” approach is ineffective. Flexibility needed for service providers to work across sectors to manage complex social problems. |

| Boone Blanchard, S., et al., (2021). Confronting racism and bias within early intervention: The responsibility of systems and individuals to influence change and advance equity | United States | Discussion paper in peer-reviewed publication | Children 0–5 years | Policies needs go beyond maternal-infant health policies and include the early years of life. Need a health in all policies framework that includes employment, family leave, social systems and health care. Focus on fixing the system and not the child. | Participation and partnerships; anti-racism and anti-oppression practices and policies; trauma-informed approaches; anti-racism and anti-bias training; accountability systems; governance and leadership in social and public policies. |

| Dodge, K. A. (2018). Toward population impact from early childhood psychological interventions | United States | Peer-reviewed publication synthesizing published literature and empirical research | Children 0–5 years | Services need to align with children’s needs and evidence-based services need to be readily available with improved continuity between services. Need to catalogue community programs to find where gaps exist. | Political buy-in and ownership; accountability systems through data collection and action; Place-based approach; combine top-down approach to improve determinants of health and neighborhood or local level targeted community resources; tailor to local contexts; data tracking and accountability systems. |

| Gerlach, A. J., et al., (2018). Relational approaches to fostering health equity for Indigenous children through early childhood intervention | Canada | Peer-reviewed publication reporting on qualitative study | Indigenous parents and early child development providers in urban centres | Relational perspective of family well-being and relational approaches to early child development programming | Inseparability between family well-being and child health equity; socially-responsive and tailored relational approaches and broader scope of practice. |

| Early Intervention Foundation (2020). Adverse childhood experiences: What we know, what we don’t know, and what should happen next | United Kingdom | Research report | Children, young people and families | Ongoing misconceptions about adverse childhood experiences. There are no quick fixes and need for comprehensive public health approaches in local communities. | Comprehensive system to support healthy communities and families; early years needs to extend into educational system. |

| Janus, M., et al., (2021). Population-level data on child development at school entry reflecting social determinants of health: A narrative review of studies using the early developmental instrument | International | Peer-reviewed publication reporting on narrative review | Children 0–5 years | The Early Development Instrument (EDI) is an effective tool for monitoring children’s developmental health and increasing understanding on impacts of adverse social determinants. Universal interventions may not be effective at meeting the needs of children with increased neighborhood-level adversity and/or in socio-economically marginalized families. | Holistic and neighborhood-level, intersectoral interventions to address social determinants of health. |

| Hickey, S., et al., (2021). A call for action that cannot go to voicemail: Research activism to urgently improve indigenous perinatal health and wellbeing | Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand, United States, Canada | Discussion paper in peer-reviewed publication | Indigenous families | Urgent need for adequately funded Indigenous-led solutions to address perinatal health inequities for Indigenous families in high-income settler-colonial countries. | Privileging of Indigenous knowledges and solutions; Indigenous governance; continuity of care; focus on family well-being; strengths-based; improving “cultural capabilities of non-Indigenous staff”. |

| Loock, C., et al., (2020). Social pediatrics: A model to confront family poverty, adversity, and housing instability and foster healthy child and adolescent development and resilience | Canada | Book chapter on social pediatrics model | Children and families from structurally vulnerable, low-income communities | Social pediatrics model involves primary care clinic, specialty outreach and legal aid through place- and strengths-based, localized care with emphasis on horizontal partnerships and communication. Effective at providing holistic care from prenatal to child to youth to families within the context of the community. | Integrated management and team approach; responsive and relational care; neighborhood-level access; intersectoral support; shared decision making; bottom-up demand; place-based approaches; validation of community-based knowledge and expertise; child-led, community-driven responses. |

| McBride, D., et al., (2021). Family hubs, Stockton-on-Tees: Early childhood services case example | United Kingdom | Report on case study example | Children 0–19 years and families | Family hubs require strong leadership and visioning to provide whole-family support that builds on existing relationships and communication and embody core values such as respect, inclusiveness, honesty, compassion, cooperation and humility. | Wholistic family hub model (integrated care, community-level needs, tailored programs); case management; universal programming and targeted programming; outreach services; systems navigation; relational and reflective practices; strong leadership and vision; strengths-based; build upon existing relationships and intersectoral partners. |

| Richter, L. M., et al., (2017). Investing in the foundation of sustainable development: pathways to scale up for early childhood development | International | Discussion paper in peer-reviewed publication | Young children and families | Data is needed to monitor the implementation of policies and requires multiple forms of knowledge and expertise, intersectoral partnerships with government and policy makers and mobilization of parents, families and communities. Calls for United Nations Special Advisor for Early Childhood Development as a way to put the issue high on political agendas, facilitate coordination and promote accountability. | Intersectoral action; community-led and driven; political buy-in and top-down leadership and governance; holistic continuum of care from prenatal to adolescent and women’s health; outreach; political buy-in and need better research and data-driven evaluations; flexibly adapted at the local level with sharing of responsibility; health in all policies; monitor adoption of and implementation of policies and funding; build local capacity. |

| Ritte, R., et al., (2016). An Australian model of the First 1000 days: An Indigenous-led process to turn an international initiative into an early-life strategy benefiting Indigenous families | Australia | Discussion paper in peer-reviewed publication | Preconception to early years | Empirical evidence needed for the future well-being of future generations. Need for community-informed, strengths-based data and decolonizing research and methodologies, community governance; cultural responsiveness and cultural safety. Need to build capacity of families and healthcare and allied workforce. | Intersectoral action; community participation and co-creation and leading; integrated services; health promotion holistic focus on health and wellness including a focus on families and communities; strengths-based approaches; community leaderships; whole-service approaches; microfinancing; local adaptation; improvement of quality indicators and measures and accountability systems. |

| Tyler, I., et al., (2018). It takes a village: a realist synthesis of social pediatrics program. | Canada, USA, Europe, Australia | Peer-reviewed publication reporting on realist review | Children and families from structurally vulnerable, low-income communities | Child is viewed in context of society, neighborhood, and family. Four consistent patterns of care that may be effective in social pediatrics: (1) horizontal partnerships based on willingness to share status and power; (2) bridged trust initiated through previously established third party relationships; (3) knowledge support increasing providers’ confidence and skills for engaging community; and (4) increasing vulnerable families’ self-reliance through empowerment strategies. | Holistic focus; community participation and partnerships; intersectoral actions. Trauma-informed and strengths-based approaches, acknowledgement of family and community expertise; intersectoral collaboration and partnerships with providers, children, and families; sharing of power; relational approaches to care. |

| VicHealth. (2015). Promoting equity in early childhood development for health equity through the life course | Australia | Report synthesizing “current evidence” | Prenatal-8 years | Health and social policies that support health of parents, young children and the conditions in which families work and live; equitable access to healthcare and social care for families; interventions should be universal, but the level of support needs to be proportionate to need. | Collective approach to leadership and governance; community development; targeted neighborhood or geographic locations; universalistic with targeted interventions; intersectoral and cross sectoral actions; social participation and engagement and trust; universal primary care services alongside local-tailored and responsive service provision. |

| Wettergren, B., et al., (2016). Child health systems in Sweden | Sweden | Discussion paper in peer-reviewed publication | Prenatal to 18 years | Children and families involved in decision making, information systems and quality improvements. Integrated system of maternity, child, preschool and school health care that is mid-wife or nurse-led. National public health policies are supportive of parenting role, health promotion and universal outreach with extra support for structurally vulnerable families. | Comprehensive, integrated and responsive system integrating prenatal care with early years and early grades in school; focus on health promotion |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gerlach, A.J.; McFadden, A. Re-Envisioning an Early Years System of Care towards Equity in Canada: A Critical, Rapid Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9594. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159594

Gerlach AJ, McFadden A. Re-Envisioning an Early Years System of Care towards Equity in Canada: A Critical, Rapid Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9594. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159594

Chicago/Turabian StyleGerlach, Alison Jayne, and Alysha McFadden. 2022. "Re-Envisioning an Early Years System of Care towards Equity in Canada: A Critical, Rapid Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 9594. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159594

APA StyleGerlach, A. J., & McFadden, A. (2022). Re-Envisioning an Early Years System of Care towards Equity in Canada: A Critical, Rapid Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9594. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159594