Health Status and Access to Healthcare for Uninsured Migrants in Germany: A Qualitative Study on the Involvement of Public Authorities in Nine Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

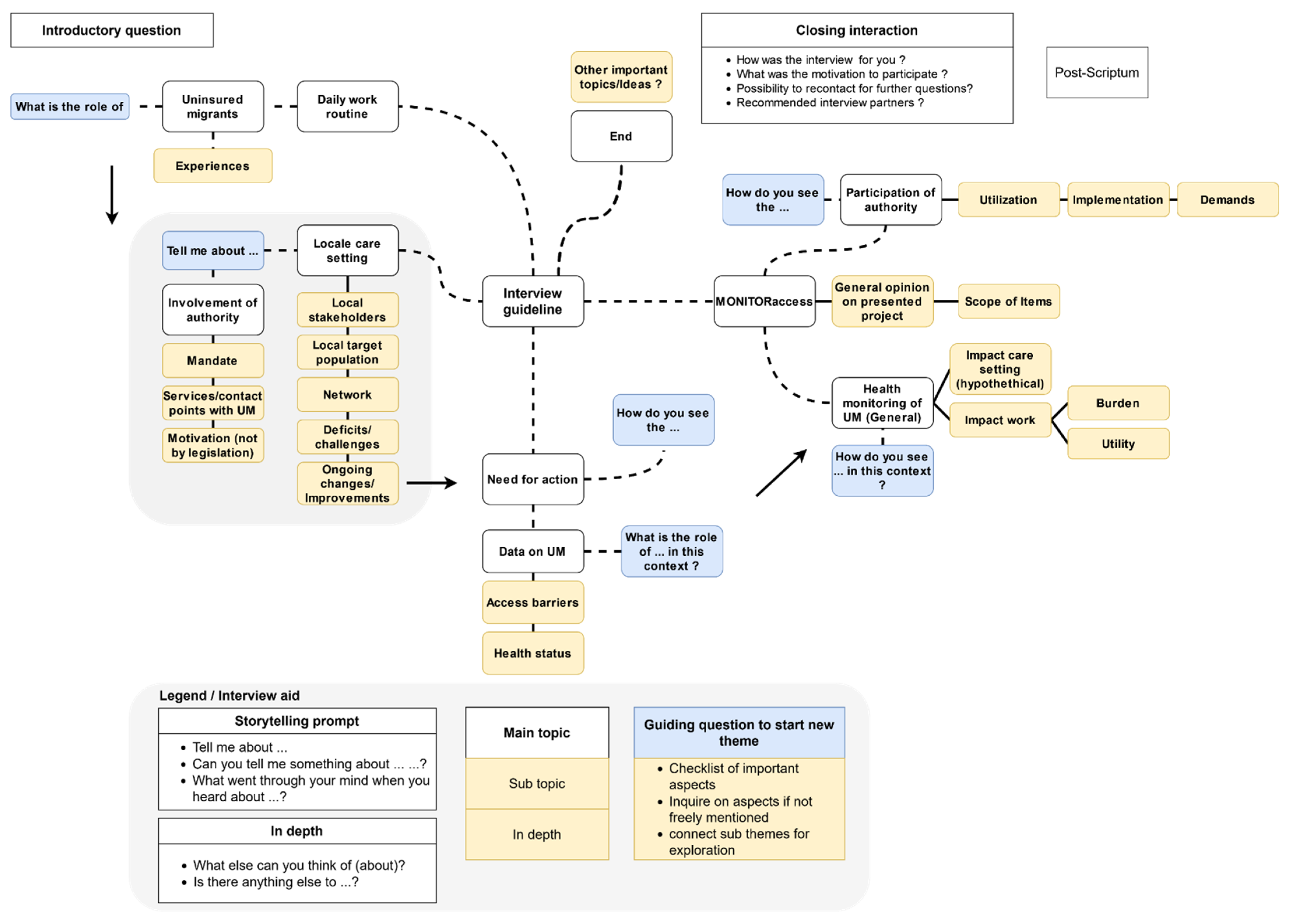

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sampling and Data Collection Methods

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Interviews and Participants

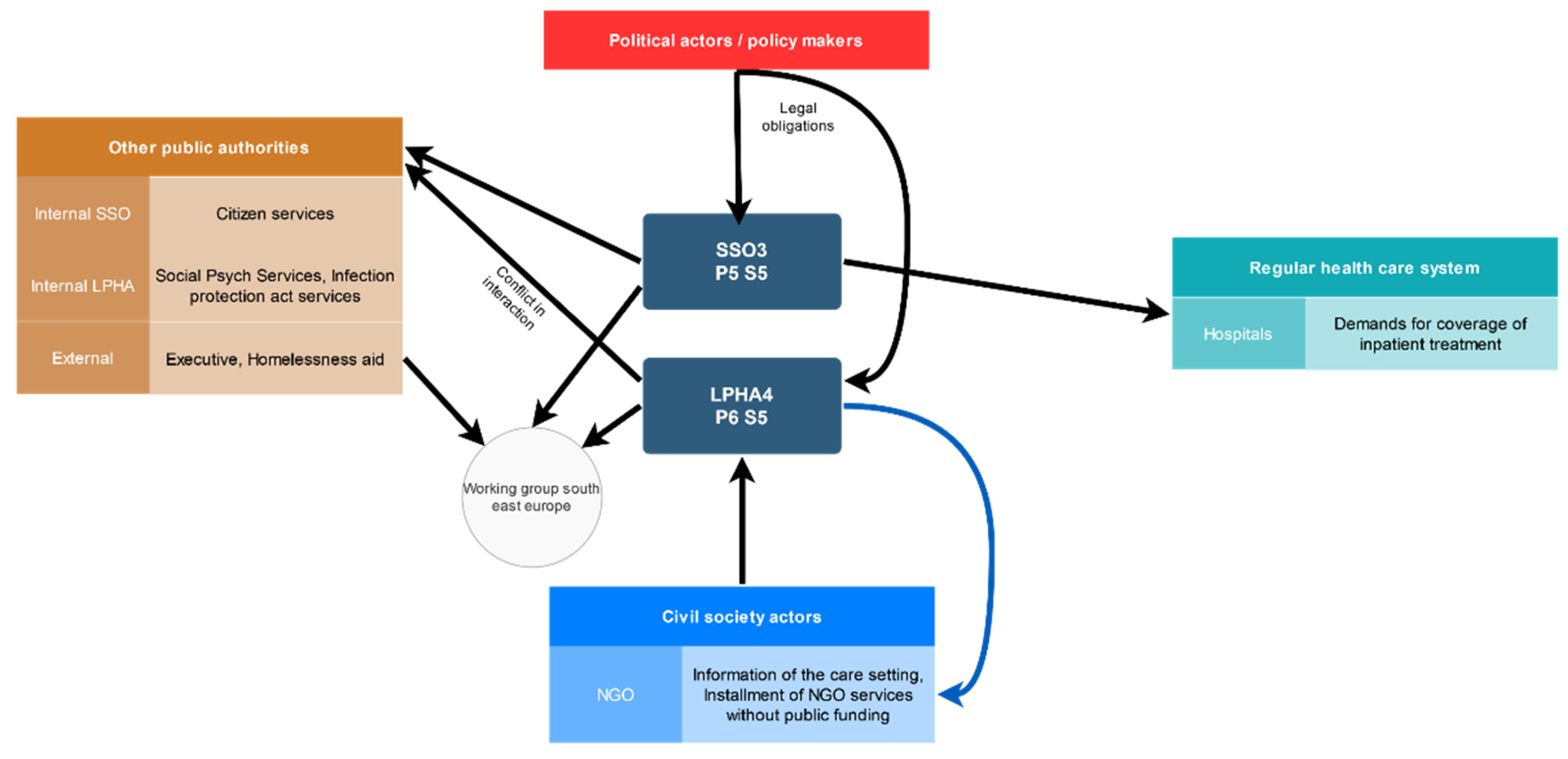

3.2. Role and Involvement of Local Health Authorities in Individual Health Services

3.3. Role and Involvement of Social Serive

“Of course, we can’t say that much about illegal immigrants, who are usually people who have applied for asylum at some point and have been rejected, who must actually leave the country or be expelled, and who then go into hiding. Of course, they don’t dare to come to us as authority because they know that the moment they arrive here, we would have to inform the immigration authority that someone is here illegally.”(P5)

“The theory is that, if you believe the politicians, everyone is theoretically insured, that’s how it looks at first, but in practice, unfortunately, it looks quite different because the assumption that people from abroad bring [a health] insurance with them and therefore have this EHIC [European Health Insurance Card] is often not true. So for us this is a big problem, first of all that we are confronted again and again with the people and of course we know exactly if we do not grant any benefits there is usually no insurance coverage.”(P5)

“So there are all kinds of parallel structures that should actually lead to everyone being insured, which are first of all totally complicated, and besides, it’s not like everyone is insured, so there are still enough uninsured. And I think that the German state can’t afford to make such a mess <laughs>.”(P5)

3.4. Reported Themes of Challenges

3.4.1. Services in the Framework of the Infection Protection Act

“Who pays for the medication costs, which can reach hundreds of euros? My colleague also has certain collaborations with doctors where it is always possible to care for someone, but these are really very small, isolated solutions. If we had more, I don’t know how it would be. […] You cannot pay for HIV medication as an NGO or as a city for the entire life.”(P2)

3.4.2. Pregnancy

“Every woman who comes here for antenatal care has a gynaecologist who is responsible for her and, in parallel, a social worker. Her job is to make sure that the woman is safe. To secure the delivery, that they, if they are undocumented women, can legalise themselves through an exceptional leave to remain. That they have a place to live, that they have financial security and, of course, that the costs for childbirth are covered by the social welfare office”(P8)

“[Uninsured] women had to be referred to the hospital during pregnancy, because they had been treated by our outpatient gynaecologists with whom we cooperate, who at some point were no longer able to assume medical responsibility […] This was not considered an emergency, although it would have led to one for the child and the mother, if not treated. Accordingly, women often discharged themselves from the hospital early. Nevertheless, they received a huge bill for several thousand euros. A consequence of this, one does not know whether it arose despite or because of the shortened stay, a stillbirth occurred. And sometimes the stillbirth was considered an emergency for curettage or stillbirth, sometimes not.”(P2)

3.4.3. Chronic Disease and In-Patient Treatment

“So the fact that the two drop-in centres are very well connected with doctors, who then also work free of charge, is certainly not bad, but of course it is still unsatisfactory when sick people are dependent on good will. We would prefer to have it regulated in an orderly manner. Not to belittle this commitment or saying that it is not necessary, I would say that it is a stopgap (“Notnagel”) that works quite well.”(P11)

“And the other day there was an enquiry about treatment costs for an operation on a tumour of 12,000 euros. And then of course you must think, okay, that would somehow take 5% of my budget away in one swoop. And then you try to somehow find a solution with the [NGOs] by saying: okay, we also have services that are financed by donations, and on the other hand, you say we will contribute half of the costs and the civil society will pay the other half.”(P4)

3.4.4. Mental Health

“Au pairs were a big problem in the pregnancy counselling centre. Au pairs with unbelievably bad health insurance that excluded everything that was not acute, but who were mostly pregnant or sometimes also needed psychotherapeutic treatment, so that this inadequate care should perhaps also be taken into account.”(P10)

3.4.5. Socio-Legal Clearing

“There is an employee who is responsible from the immigration authority, with whom there are meetings and agreements. Nevertheless, all that is discussed there is then actually different again and the women must run repeatedly to hearings, for example, and are sent away, are treated badly, are put down, the situation is always different from what was actually agreed on.”(P8)

“Homelessness, that is a very big issue with [women from the EU]. They are actually worse off than women without a residence permit. I know that 12 weeks before they give birth they will be cared for and if the father of the child has been found by then and they can secure their stay here through the father of the child, then I know that their lives will continue. So then they will be able to stay here and build up their lives. Unfortunately, it’s quite different for people from EU countries. They are here with a legal residence permit and are allowed to live here, but it is very difficult for them to acquire a claim to social benefits or health insurance.”(P8)

3.5. Development of Local Care Settings

3.5.1. Role of Public Authorities

“And with that [case] we then went out and contacted churches. I think this woman’s case has moved a lot in some people’s minds, I would say. There were a few others, but it also led to churches and hospital chaplains joining in and doing something. But the local authority was actually much of a driving force in the whole story.”(P3)

“Ultimately, this target group needs a political lobby, and someone has to make a strong case for this. We can promote this by advocating offers such as the [drop-in centre for uninsured migrants].”(P6)

3.5.2. Outsourcing

“We are still trying to expand a network of specialists, because we only have general practitioners and a paediatrician here at the office. That means we try to cover all other specialties through cooperation with registered doctors with corresponding agreements where it then costs less or is partly done free of charge.”(P2)

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Results

4.2. Discussion of Results

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blümel, M.; Spranger, A.; Achstetter, K.; Maresso, A.; Busse, R. Germany: Health system review. In Health Systems in Transition; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, S.; Clarke, D.; Gottlieb, N.; Quentin, W. Legal Access Rights to Health Care: Country Profile: Germany; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/uhc-law-in-practice-legal-access-rights-to-health-care-country-profile-germany (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Angaben zur Krankenversicherung—Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus; Statistisches Bundesamt: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Service/Bibliothek/_publikationen-fachserienliste-13.html (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Offe, J.; Bozorgmehr, K.; Dieterich, A.; Trabert, G. Parallel Report to the CESCR on the Right to Health for Non-Nationals: On the 6th Periodic Report of the Federal Republic of Germany on the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; Prepared for the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 64th Session. 2018. Available online: https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CESCR/Shared%20Documents/DEU/INT_CESCR_CSS_DEU_32476_E.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Loi, S.; Vilhena, D.V.D. Exclusion through statistical invisibility. An exploration on what can be known through publicly available datasets on irregular migration and the health status of this population in Germany. In MPIDR Working Paper; Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research: Rostock, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razum, O.; Bozorgmehr, K. Restricted entitlements and access to health care for refugees and immigrants: The example of Germany. Glob. Soc. Policy 2016, 16, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundestag. Gesetz über die allgemeine Freizügigkeit von Unionsbürgern. 2004. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/freiz_gg_eu_2004/BJNR198600004.html (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Bundestag. Gesetz zur Regelung von Ansprüchen ausländischer Personen in der Grundsicherung für Arbeitsuchende nach dem Zweiten Buch Sozialgesetzbuch und in der Sozialhilfe nach dem Zwölften Buch Sozialgesetzbuch. 2016. Available online: https://dip.bundestag.de/vorgang/.../77237 (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Bozorgmehr, K.; Dieterich, A.; Offe, J. UN concerned about the right to health for migrants in Germany. Lancet 2019, 393, 1202–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, C.; Offe, J.; McMeekin, K. Deprived of the Right to Health. Sick and without Medical Care in Germany; Ärzte der Welt e.V.: Munich, Germany, 2018; Available online: https://issuu.com/arztederwelt/docs/aedw_observatory_2018_kurzfassung_f (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Lotty, E.Y.; Hammerling, C.; Mielck, A. Gesundheitszustand von Menschen ohne Krankenversicherung und von Menschen ohne legalen Aufenthaltsstatus: Analyse von Daten der Malteser Migranten Medizin (MMM) in München. Gesundheitswesen 2015, 77, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitschke, H.; Oliveira, F.; Knappik, A.; Bunte, A. Seismograf für Migration und Versorgungsdefizite—STD-Sprechstunde im Gesundheitsamt Köln. Gesundheitswesen 2011, 73, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schade, M.; Heudorf, U.; Tiarks-Jungk, P. Die Humanitare Sprechstunde in Frankfurt am Main: Inanspruchnahme nach Geschlecht, Alter und Herkunftsland. Gesundheitswesen 2015, 77, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallmann, M. Bericht Baustein 3: Auswertung zu Klient*innen-Daten und Kostenübernahmen (Routinedaten); Institut Für Innovation und Beratung an der Evangelischen Hochschule Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mylius, M.; Frewer, A. Medizinische Versorgung von Migrantinnen und Migranten ohne legalen Aufenthaltsstatus—Eine Studie zur Rolle der Gesundheitsamter in Deutschland. Gesundheitswesen 2014, 76, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylius, M.; Frewer, A. Access to healthcare for undocumented migrants with communicable diseases in Germany: A quantitative study. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 582–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bommes, M.; Wilmes, M. Menschen ohne Papiere in Köln; Institut für Migrationsforschung und Interkulturelle Studien (IMIS): Osnabrück, Germany, 2007; Available online: https://www.imis.uni-osnabrueck.de/en/research/1_migration_regimes/completed_research_projects_1/menschen_ohne_papiere_in_koeln.html (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Vogel, D.; Aßner, M.; Mitrović, E.; Kühne, A. Leben ohne Papiere: Eine Empirische Studie zur Lebenssituation von Menschen ohne Gültige Aufenthaltspapiere in Hamburg; Diakonisches Werk Hamburg: Hamburg, Germany, 2009; Available online: https://www.ew.uni-hamburg.de/ueber-die-fakultaet/personen/neumann/files/diakonie-endfassung.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Anderson, P.; Chevenas, M.; Gavranidou, M.; Hämmerling, C.; Knickenberg, J.; Monat, M.; Spohn, M.; Poppert, B.; Vollmer, C. “Wir haben Sie nicht vergessen …” 10 Jahre Umgang mit Menschen ohne gesicherten Aufenthaltsstatus in der Landeshauptstadt München: Das Münchner Modell; Sozialreferat, Stelle für Interkulturelle Arbeit: Munich, Germany, 2010; Available online: https://www.forum-illegalitaet.de/mediapool/99/993476/data/Muenchen_Ergebnisse_2010.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Gesetz zur Verhütung und Bekämpfung von Infektionskrankheiten beim Menschen (Infektionsschutzgesetz, IfSG, Infection Protection Act) § 19 Aufgaben des Gesundheitsamtes in besonderen Fällen. 2000. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/ifsg/__19.html (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Platform for international cooperation on undocumented Migrant (PICUM). Guaranteeing Access to Health Care for Undocumented Migrants in Europe: What Role Can Local and Regional Authorities Play? Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrant (PICUM): Brussels, Belgium, 2013; Available online: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/pdf/cor_report_access_to_healthcare_en_fr_it_es_2013.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Noest, S.; Jahn, R.; Bader, C.; Martis-Cisic, R.; Moser, V.; Kratzsch, L.; Bozorgmehr, K. Monitoring care of uninsured migrants in Germany. A feasibility study. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, A. Wer ist ein Experte? Wissenssoziologische Grundlagen des Expertinneninterviews. In Interviews mit Experten: Eine Praxisorientierte Einführung; Bogner, A., Littig, B., Menz, W., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Meuser, M.; Nagel, U. Das Experteninterview—Konzeptionelle Grundlagen und methodische Anlage. In Methoden der vergleichenden Politik- und Sozialwissenschaft; Pickel, S., Pickel, G., Lauth, H.-J., Jahn, D., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2005; pp. 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, F.; Kalantaryan, S.; Scipioni, M.; Alessandrini, A.; Pasa, A. Migration in EU Rural Areas; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausarbeitung: Die Gesundheitsdienstgesetze der Länder; Wissenschaftliche Dienste Deutscher Bundestag: Berlin, Germany, 2015; Available online: https://docplayer.org/105654616-Deutscher-bundestag-ausarbeitung-die-gesundheitsdienstgesetze-der-laender-wissenschaftliche-dienste-deutscher-bundestag-wd-14.html (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Witzel, A. The problem-centered interview. Forum Qual. Soz. 2000, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gläser, J.; Laudel, G. Experteninterviews und Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse als Instrumente Rekonstruierender Untersuchungen, 3rd ed.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, R.; Schreyögg, J.; Gericke, C. Analyzing Changes in Health Financing Arrangements in High-Income Countries: A Comprehensive Framework Approach. 2007. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/13711 (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Schreyögg, J.; Stargardt, T.; Velasco-Garrido, M.; Busse, R. Defining the “health benefit basket” in nine european countries. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2005, 6, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gesetz über den Aufenthalt, die Erwerbstätigkeit und die Integration von Ausländern im Bundesgebiet (Residence act) § 87 Übermittlungen an Ausländerbehörden. 2008. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/aufenthg_2004/__87.html (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- MediFonds, E.V. Verzeichnis Anonyme Behandlungsscheine, Clearingstellen und Gesundheitsfonds. Available online: https://anonymer-behandlungsschein.de/ (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Linke, C.H.C.; Holzinger, F. ‘Managing scarcity’—A qualitative study on volunteer-based healthcare for chronically ill, uninsured migrants in Berlin, Germany. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiter, S.; Bermpohl, F.; Krausz, M.; Leucht, S.; Rossler, W.; Schouler-Ocak, M.; Gutwinski, S. The Prevalence of Mental Illness in Homeless People in Germany. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2017, 114, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mylius, M. Krankenhausaufenthalte von Migrantinnen und Migranten ohne Krankenversicherung—Eine explorative Studie zur stationaren Versorgung in Niedersachsen, Berlin und Hamburg. Gesundheitswesen 2016, 78, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda, H. Medical aid as protest: Acts of citizenship for unauthorized im/migrants and refugees. Citizensh. Stud. 2013, 17, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, M.; Nielsen, S.; Hamouda, O.; Bremer, V. Angebote der Beratungsstellen zu sexuell übertragbaren Infektionen und HIV und diesbezügliche Datenerhebung in deutschen Gesundheitsämtern im Jahr 2012. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2013, 56, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mullerschon, J.; Koschollek, C.; Santos-Hovener, C.; Kuehne, A.; Muller-Nordhorn, J.; Bremer, V. Impact of health insurance status among migrants from sub-Saharan Africa on access to health care and HIV testing in Germany: A participatory cross-sectional survey. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2019, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottie, K.; Lotfi, T.; Kilzar, L.; Howeiss, P.; Rizk, N.; Akl, E.A.; Dias, S.; Biggs, B.-A.; Christensen, R.; Rahman, P.; et al. The Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Screening for HIV in Migrants in the EU/EEA: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myran, D.T.; Morton, R.; Biggs, B.-A.; Veldhuijzen, I.; Castelli, F.; Tran, A.; Staub, L.P.; Agbata, E.; Rahman, P.; Pareek, M. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening for and vaccination against hepatitis B virus among migrants in the EU/EEA: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenner, D.; Hafezi, H.; Potter, J.; Capone, S.; Matteelli, A. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening migrants for active tuberculosis and latent tuberculous infection. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2017, 21, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, K.; Jarvis, C.; Munoz, M.; D’Souza, V.; Graves, L. Undocumented Pregnant Women: What Does the Literature Tell Us? J. Immigr. Minority Health 2013, 15, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, C.; Munoz, M.; Graves, L.; Stephenson, R.; D’Souza, V.; Jimenez, V. Retrospective review of prenatal care and perinatal outcomes in a group of uninsured pregnant women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2011, 33, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, L.R.; Cornelius, W.A.; Jones, O.W. Utilization of health services by Mexican immigrant women in San Diego. Women Health 1986, 11, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, P.; Haumont, D.; Degueldre, M. Devenir obstétrical et périnatal des patientes sans couverture sociale. Rev. Médicale De Brux. 1994, 15, 366–370. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.M.; Westfall, J.M.; Bublitz, C.; Battaglia, C.; Fickenscher, A. Birth outcomes in Colorado’s undocumented immigrant population. BMC Public Health 2005, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, H.; Epiney, M.; Lourenco, A.P.; Costanza, M.C.; Delieutraz-Marchand, J.; Andreoli, N.; Dubuisson, J.-B.; Gaspoz, J.-M.; Irion, O. Undocumented migrants lack access to pregnancy care and prevention. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, S.A.; Kenney, G.M.; Ellwood, M.R. Medicaid coverage of maternity care for aliens in California. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 1996, 28, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejeune, C.; Fontaine, A.; Crenn-Hebert, C.; Paolotti, V.; Foureau, V.; Lebert, A. Recherche-action sur la prise en charge médico-sociale des femmes enceintes sans couverture sociale. J. Gynécologie Obs. Biol. Reprod. 1998, 27, 772–781. [Google Scholar]

- Neupert, I.; Pieper, C. Menschen ohne Krankenversicherung—Prävalenz und Rückführung in die sozialen Sicherungssysteme durch den Sozialdienst am Beispiel des Universitätsklinikums Essen. Gesundheitswesen 2020, 82, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibelhofer, E.; Holzinger, C. ‘Damn It, I Am a Miserable Eastern European in the Eyes of the Administrator’: EU Migrants’ Experiences with (Transnational) Social Security. Soc. Incl. 2018, 6, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanari, D.B.O.; Minelli, L. Self-perceived health among Eastern European immigrants over 50 living in Western Europe. Int. J. Public Health 2015, 60, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)—Resolution 2200A (XXI). 16 December 1966. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cescr.aspx (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- United Nations Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights. Substantive Issues Arising in the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: General Comment No.14 (2000)—The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health. E/C.12/2000/4. 2000. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/425041 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Gesetz zu dem Internationalen Pakt vom 19. Dezember 1966 über Wirtschaftliche, Soziale und Kulturelle Rechte. 1973. Available online: http://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/start.xav?startbk=Bundesanzeiger_BGBl&jumpTo=bgbl273062.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Mylius, M.D.J.; Zuhlke, C.; Mertens, E. Hemmnisse abbauen, Gesundheit fordern—Die Gesundheitsversorgung von Migrierten ohne Papiere im Rahmen eines Modellprojektes in Niedersachsen, 2016–2018. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2019, 62, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozorgmehr, K.; Wenner, J.; Nöst, S.; Stock, C.; Razum, O. Germany: Financing health services provided to asylum seekers. In Compendium of Health System Responses to Large-Scale Migration in the WHO European Region; World Health Organization WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, A.W.; Weis, J.; Janho, L.; Biddle, L.; Bozorgmehr, K. Die elektronische Gesundheitskarte für Asylsuchende. Zusammenfassung der wissenschaftlichen Evidenz. In Health Equity Studies & Migration—Report Series (2021-02); heiDOK—The Heidelberg Document Repository: Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgmehr, K.; Razum, O. Effect of restricting access to health care on health expenditures among asylum-seekers and refugees: A quasi-experimental study in Germany, 1994–2013. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nöst, S.; Jahn, R.; Aluttis, F.; Drepper, J.; Preussler, S.; Qreini, M.; Breckenkamp, J.; Razum, O.; Bozorgmehr, K. Health and primary care surveillance among asylum seekers in reception centres in Germany: Concept, development, and implementation. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2019, 62, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgmehr, K.; Razum, O. Lost in Ambiguity: Facilitating access or upholding barriers to health care for asylum seekers in Germany. In Refugees in Canada and Germany: From Research to Policies and Practice; Social Science Open Access: Online, 2020; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Bozorgmehr, K.; Jahn, R. Adverse health effects of restrictive migration policies: Building the evidence base to change practice. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e386–e387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main topic | How is your authority connected to the care for uninsured people here in [name of city]? |

| Subtopic | Now you have just named a very concrete offer where the uninsured can theoretically go, are there other contact points? |

| In depth | Would you say that in general there are enough offers? |

| Authority | Interview Partner | Setting | Counselling—Infectious Disease | Counselling—Pregnancy | Social Psychiatric Service | Diagnostics—Infectious Disease | Diagnostics—Sexual Health/Gynaecology | Treatment—Infectious Disease | Treatment—General Medical | Birth Programme | Socio-Legal Clearing | No Data Work | Routine Data Work | Targeted Data Work | Publication of Data Work | Funding of NGO Services | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPHA1 | P1 | S1 | X | X 1 | X | X | X | X 2 | |||||||||

| LPHA2 | P2 | S3 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X 3 | X | X | X | X | X 4 | |||

| LPHA3 | P3 | S4 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X 5 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| LPHA4 | P6 | S5 | X | X | X | X | X 6 | ||||||||||

| LPHA5 | P8 | S6 | X | X | X | X | X | X 7 | X | X 7 | X | ||||||

| LPHA6 | P9 | S7 | X | X | X | X | X | X 8 | |||||||||

| LPHA7 | P10 | S2 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X 9 |

| Category | Reported Challenges |

|---|---|

| In-patient needs | Expensive and lengthy treatments: oncological diseases, high-risk pregnancies, surgery, budget decisions with ethical implications |

| Chronic disease | Costs for regular diagnostics, cost of regular medication, i.e., HIV, hepatitis and diabetes |

| EU Citizens | EU foreigners in old age who live with their children who work in Germany; Multi-vulnerability: Pregnancy and homelessness, addiction and homelessness, complex legal constellation preventing access to social welfare, repeated migration |

| Irregular migrants | UM who do not want to expose their irregular status when financing of treatment is needed cannot be helped by public authorities |

| Inter-authority | Conflicts of interest between health and immigration authorities, refusal of jurisdiction between authorities |

| Other | Cost coverage for treatment of diseases identified in IfSG services |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kratzsch, L.; Bozorgmehr, K.; Szecsenyi, J.; Nöst, S. Health Status and Access to Healthcare for Uninsured Migrants in Germany: A Qualitative Study on the Involvement of Public Authorities in Nine Cities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6613. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116613

Kratzsch L, Bozorgmehr K, Szecsenyi J, Nöst S. Health Status and Access to Healthcare for Uninsured Migrants in Germany: A Qualitative Study on the Involvement of Public Authorities in Nine Cities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6613. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116613

Chicago/Turabian StyleKratzsch, Lukas, Kayvan Bozorgmehr, Joachim Szecsenyi, and Stefan Nöst. 2022. "Health Status and Access to Healthcare for Uninsured Migrants in Germany: A Qualitative Study on the Involvement of Public Authorities in Nine Cities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 11: 6613. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116613

APA StyleKratzsch, L., Bozorgmehr, K., Szecsenyi, J., & Nöst, S. (2022). Health Status and Access to Healthcare for Uninsured Migrants in Germany: A Qualitative Study on the Involvement of Public Authorities in Nine Cities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6613. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116613