Evaluating Outdoor Nature-Based Early Learning and Childcare Provision for Children Aged 3 Years: Protocol of a Feasibility and Pilot Quasi-Experimental Design

Abstract

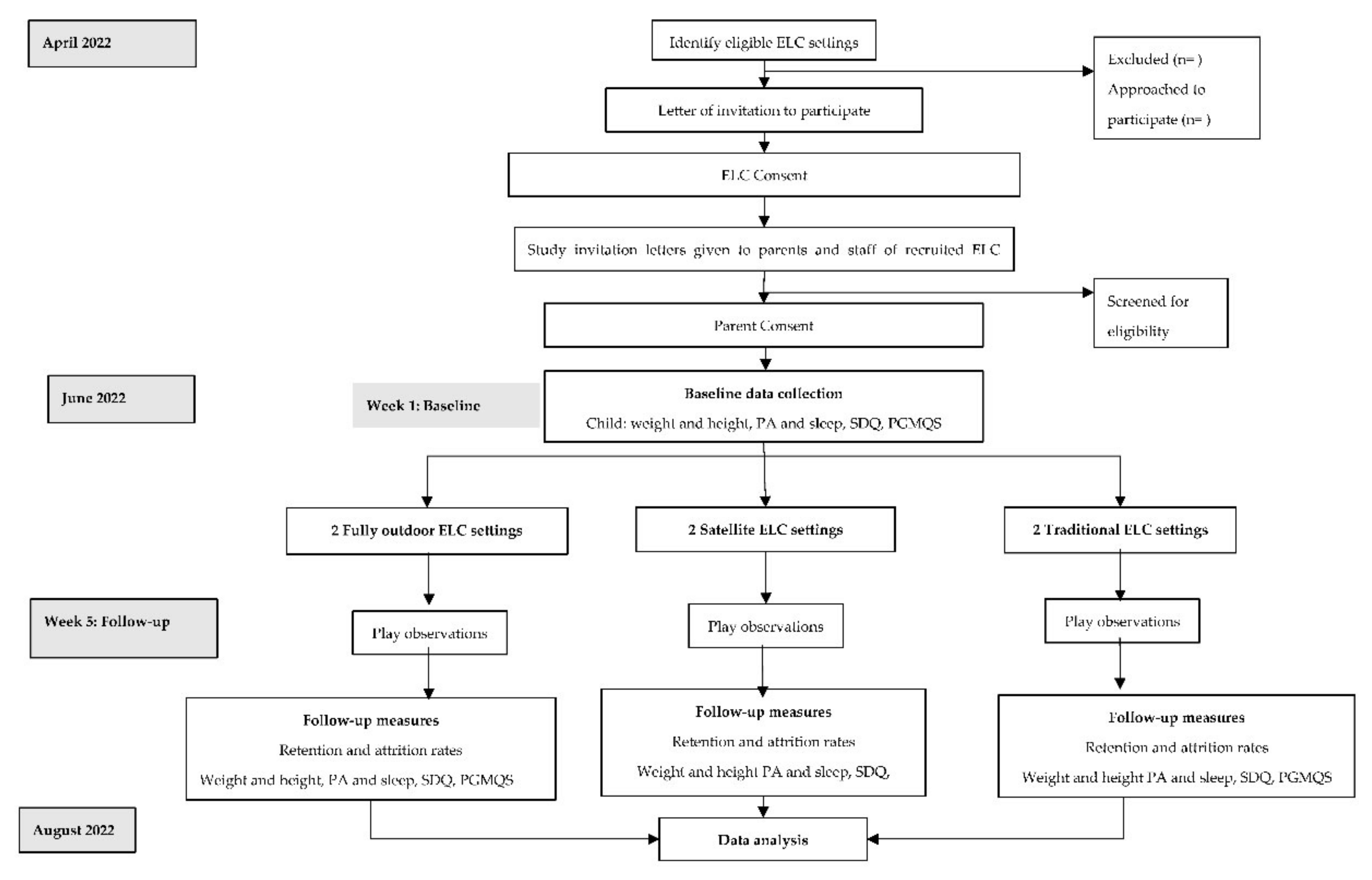

:1. Introduction

- (i).

- Fully outdoor setting, where children spend most of their time in a forest or park with many natural affordances;

- (ii).

- Indoor/outdoor, where children can move freely between the indoor and outdoor area of their ELC setting;

- (iii).

- (Satellite, where the ELC has a nature space (e.g., forest or park), but it is not on their physical premises;

- (iv).

- Traditional ELC setting, often attached to a primary school, where children spend most of their time indoors but with the opportunity to experience the outdoor environment (built and/or natural) as part of structured sessions or play breaks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Initial Phases

2.1.1. Phase One: Development of Logic Model

2.1.2. Phase Two: Evaluability Assessment with Key Stakeholders, Refinement of Logic Model, ToC, and Identification of Evaluation Goals

2.2. Study Design

Feasibility and Pilot Study

2.3. Ethics Approval

2.4. Setting

2.5. Participants

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.6. Sample Size

2.7. Recruitment

2.8. Measures

- Number of eligible ELC settings that were approached to participate in the study.

- Number of ELC settings that expressed an interest in taking part, number of ELC settings that declined an invitation to take part, and number of ELC settings that did not respond.

- Number of eligible children who were approached to participate in the study.

- Number of children whose parents consent for them to participate and number of children who did not have consent to participate.

- Number of participating children who leave the ELC setting after the study has begun.

- Attendance records of participating children will be collected throughout the study timeline to determine retention rates.

- Number of children assigned a propensity score.

- Number of successful matches using propensity score.

- The completeness of the measurement assessments from baseline to follow-up.

- Which measurement tools demonstrate a positive, negative, or null effect between exposure and comparison groups from baseline to follow-up.

- The acceptability of the measurement tools within the study population.

2.8.1. Progression Criteria

2.8.2. Measurement Tools

Demographic Questionnaire

Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

Height and Weight

Preschooler Gross Motor Quality Scale (PGMQS)

Physical Activity, Sedentary Time, and Sleep

Play Behaviour

Semi-Structured Interviews

Monitoring and Evaluation Tools

2.9. Analysis

2.9.1. Data Management

2.9.2. Recruitment

2.9.3. Statistical Analysis

2.9.4. Qualitative Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Guide for Semi-Structured Interviews

| Assessing the Acceptability of Programme and Trial Methods | Purpose of Question | Normalisation Process Theory Component |

|---|---|---|

| Address participant’s views regarding implementation of the programme, identify whether participant’s views match with those from the EA workshops and findings in the literature. Can help direct data collection for full-scale evaluation. | Coherence (e.g., how easy is the programme to describe, do participants believe the programme has a clear purpose, who does the programme benefit, how does it fit with the overall goals of early years provision?) |

| Address implementation aspects of the programme, what is working and what is not. Support recommendations to stakeholders regarding how programme can be improved. | Cognitive participation (e.g., are participants committed to providing the programme, do participants believe that providing the programme is a good use of their time?) Collective action (e.g., do participants believe they are sufficiently trained to provide the programme, do they have the resources they require, is it compatible with existing work practices?) |

| Identify contextual factors that influence the implementation of the programme. | Reflexive Monitoring (e.g., participants are able reflect and critique the programme.) |

| Assess the acceptability of the study methods. | Coherence (i.e., are educators understanding of why the trial design methods have been used?) Cognitive participation (i.e., were educators supportive of the recruitment methods?) Collective action (i.e., did the study design have any impact on usual practice?) Reflexive monitoring of the trial methods is ongoing throughout the study through educator feedback and as part of the interviews. |

| Assess the acceptability of data collection methods. Identify which methods can be taken forward to a full-scale evaluation. | Coherence (i.e., do participants understand why these data collection methods are being used, how they might contribute to future implementation of the programme?) Cognitive action (i.e., were educators prepared to assist in the data collection methods, were children happy to participate?) Collective action (i.e., did educators believe they were skilled enough to support data collection, were they happy to share current monitoring and evaluation practices?) Reflexive monitoring (i.e., did participants believe that the outcomes the measurement tools were assessing important for programme implementation?) |

Appendix B. Play Observation Protocol (Adapted from Loebach and Cox 2020; Litlle, 2010)

| Variable | Code |

|---|---|

| Event | Play event number |

| Participant | Unique ID |

| Play type | (1) Physical; (2) Exploratory; (3) Imaginative; (4) Play with rules; (5) Bio/nature; (6) Expressive; (7) Restorative; (8) Digital; (9) Non-play |

| Risky behaviour/play | (1) Heights; (2) Speed; (3) Dangerous tools (4) Dangerous elements (5) Rough and tumble (6) Exploring alone (7) Impact (8) Vicarious |

| Peer interaction | (1) Solitary; (2) Parallel; (3) Cooperative; (4) Onlooking; (5) Conflict; (6) Unoccupied |

| Adult interaction | (1) No adult presenting/observing; (2) Observing; (3) Participating; (4) Directing; (5) Restricting; (6) Other |

| Environmental interaction | (LN) Loose natural; (FN) Fixed natural; (LM) Loose manufactured; (FM) Fixed manufactured |

| Play communication | (1) Play; (2) Environment; (3) Peer-social; (4) Adult-social; (5) Cowabunga!; (6) Wayfinder; (7) Instructive; (8) Care; (9)Permission seeking; (10); Self-talk; (11) Conflict |

| Interaction with coder | Yes; No |

| Open Coding | Descriptive texts |

References

- Tremblay, M.; Gray, C.; Babcock, S.; Barnes, J.; Costas Bradstreet, C.; Carr, D.; Chabot, G.; Choquette, L.; Chorney, D.; Collyer, C.; et al. Position Statement on Active Outdoor Play. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6475–6505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Felix, E.; Silva, V.; Caetano, M.; Ribeiro, M.V.; Fidalgo, T.M.; Rosa Neto, F.; Sanchez, Z.M.; Surkan, P.J.; Martins, S.S.; Caetano, S.C. Excessive Screen Media Use in Preschoolers Is Associated with Poor Motor Skills. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandseter, E.B.H.; Cordovil, R.; Hagen, T.L.; Lopes, F. Barriers for Outdoor Play in Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) Institutions: Perception of Risk in Children’s Play among European Parents and ECEC Practitioners. Child Care Pract. 2020, 26, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussoni, M.; Olsen, L.L.; Pike, I.; Sleet, D.A. Risky play and children’s safety: Balancing priorities for optimal child development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3134–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.; Atherton, F.; McBride, M.; Calderwood, C. Physical Activity Guidelines: UK Chief Medical Officers’ Report. 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/physical-activity-guidelines-uk-chief-medical-officers-report (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- Hesketh, K.R.; McMinn, A.M.; Ekelund, U.; Sharp, S.J.; Collings, P.J.; Harvey, N.C.; Godfrey, K.M.; Inskip, H.M.; Cooper, C.; van Sluijs, E.M. Objectively measured physical activity in four-year-old British children: A cross-sectional analysis of activity patterns segmented across the day. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tinner, L.; Kipping, R.; White, J.; Jago, R.; Metcalfe, C.; Hollingworth, W. Cross-sectional analysis of physical activity in 2-4-year-olds in England with paediatric quality of life and family expenditure on physical activity. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.; Ridgers, N.D.; Howard, B.J.; Winkler, E.A.; Healy, G.N.; Owen, N.; Dunstan, D.W.; Salmon, J. Light-Intensity Physical Activity and Cardiometabolic Biomarkers in US Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doré, I.; Sylvester, B.; Sabiston, C.; Sylvestre, M.P.; O’Loughlin, J.; Brunet, J.; Bélanger, M. Mechanisms underpinning the association between physical activity and mental health in adolescence: A 6-year study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnstone, A.; McCrorie, P.; Thomson, H.; Wells, V.; Martin, A. Nature-Based Early Learning and Childcare—Influence on Children’s Health, Wellbeing and Development: Literature Review; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/systematic-literature-review-nature-based-early-learning-childcare-childrens-health-wellbeing-development/ (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Janssen, X.; Martin, A.; Hughes, A.R.; Hill, C.M.; Kotronoulas, G.; Hesketh, K.R. Associations of screen time, sedentary time and physical activity with sleep in under 5s: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2020, 49, 101226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, S.; Bruijns, B.A.; Vanderloo, L.M.; O’Brien, K.T.; Johnson, A.M.; Tucker, P. Physical activity and sedentary time during childcare outdoor play sessions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2018, 108, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mygind, L.; Kjeldsted, E.; Hartmeyer, R.; Mygind, E.; Bølling, M.; Bentsen, P. Mental, physical and social health benefits of immersive nature-experience for children and adolescents: A systematic review and quality assessment of the evidence. Health Place 2019, 58, 102136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrorie, P.; Olsen, J.R.; Caryl, F.M.; Nicholls, N.; Mitchell, R. Neighbourhood natural space and the narrowing of socioeconomic inequality in children’s social, emotional, and behavioural wellbeing. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2021, 2, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, A.; McCrorie, P.; Cordovil, R.; Fjørtoft, I.; Iivonen, S.; Jidovtseff, B.; Lopes, F.; Reilly, J.J.; Thomson, H.; Wells, V.; et al. Nature-Based Early Childhood Education and Children’s Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, Motor Competence, and Other Physical Health Outcomes: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. J. Phys. Act. Health 2022, 19, 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeland, J.; Moens, M.A.; Beute, F.; Assink, M.; Staaks, J.P.; Overbeek, G. A dose of nature: Two three-level meta-analyses of the beneficial effects of exposure to nature on children’s self-regulation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankiw, K.A.; Tsiros, M.D.; Baldock, K.L.; Kumar, S. The impacts of unstructured nature play on health in early childhood development: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnstone, A.; Martin, A.; Cordovil, R.; Fjørtoft, I.; Iivonen, S.; Jidovtseff, B.; Lopes, F.; Reilly, J.J.; Thomson, H.; Wells, V.; et al. Nature-Based Early Childhood Education and Children’s Social, Emotional and Cognitive Development: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebach, J.; Cox, A. Tool for observing play outdoors (Topo): A new typology for capturing children’s play behaviors in outdoor environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulset, V.; Vitaro, F.; Brendgen, M.; Bekkhus, M.; Borge, A.I. Time spent outdoors during preschool: Links with children’s cognitive and behavioral development. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulset, V.S.; Czajkowski, N.O.; Staton, S.; Smith, S.; Pattinson, C.; Allen, A.; Thorpe, K.; Bekkhus, M. Environmental light exposure, rest-activity rhythms, and symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity: An observational study of Australian preschoolers. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 73, 101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Benefits of Nature Contact for Children. J. Plan. Lit. 2015, 30, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Loebach, J.; Little, S. Understanding the Nature Play Milieu: Using Behavior Mapping to Investigate Children’s Activities in Outdoor Play Spaces. Child. Youth Environ. 2018, 28, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H. Characteristics of risky play. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2009, 9, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H.; Kleppe, R. Outdoor Risky Play. 2019. Available online: https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/outdoor-play/according-experts/outdoor-risky-play (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Kleppe, R.; Melhuish, E.; Sandseter, E.B.H. Identifying and characterizing risky play in the age one-to-three years. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 25, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussoni, M.; Gibbons, R.; Gray, C.; Ishikawa, T.; Sandseter, E.B.H.; Bienenstock, A.; Chabot, G.; Fuselli, P.; Herrington, S.; Janssen, I.; et al. What is the Relationship between Risky Outdoor Play and Health in Children? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6423–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Care Inspectorate. My World Outdoors; Care Inspectorate: Dundee, Scotland, 2016; Available online: https://hub.careinspectorate.com/how-we-support-improvement/care-inspectorate-programmes-and-publications/my-world-outdoors/ (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Howe, N.; Perlman, M.; Bergeron, C.; Burns, S. Scotland Embarks on a National Outdoor Play Initiative: Educator Perspectives. Early Educ. Dev. 2020, 32, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, M.; Howe, N.; Bergeron, C. How and Why Did Outdoor Play Become a Central Focus of Scottish Early Learning and Care Policy? Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2020, 23, 46–66. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, S.E.; Akhtar, S.; Jackson, C.; Bingham, D.D.; Hewitt, C.; Routen, A.; Richardson, G.; Ainsworth, H.; Moore, H.J.; Summerbell, C.D.; et al. Preschoolers in the Playground: A pilot cluster randomised controlled trial of a physical activity intervention for children aged 18 months to 4 years. Public Health Res. 2015, 3, 1–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kipping, R.; Langford, R.; Brockman, R.; Wells, S.; Metcalfe, C.; Papadaki, A.; White, J.; Hollingworth, W.; Moore, L.; Ward, D.; et al. Child-care self-assessment to improve physical activity, oral health and nutrition for 2- to 4-year-olds: A feasibility cluster RCT. Public Health Res. 2019, 7, 1–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malden, S.; Reilly, J.J.; Gibson, A.M.; Bardid, F.; Summerbell, C.; De Craemer, M.; Cardon, G.; Androutsos, O.; Manios, Y.; Hughes, A. A feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial of a preschool obesity prevention intervention: ToyBox-Scotland. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019, 5, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Scottish Government. Early Education and Care; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/policies/early-education-and-care/ (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- Scottish Government. Summary Statistics for Schools in Scotland 2021; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/summary-statistics-schools-scotland/pages/6/ (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Chan, A.W.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Altman, D.G.; Mann, H.; Berlin, J.A.; Dickersin, K.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Schulz, K.F.; Parulekar, W.R.; et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: Guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013, 346, e7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccaffrey, D.F.; Griffin, B.A.; Almirall, D.; Slaughter, M.E.; Ramchand, R.; Burgette, L.F. A Tutorial on Propensity Score Estimation for Multiple Treatments Using Generalized Boosted Models. Stat. Med. 2013, 32, 3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonell, C.; Warren, E.; Melendez-Torres, G. Methodological reflections on using qualitative research to explore the causal mechanisms of complex health interventions. Evaluation 2022, 28, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow Centre for Population Health. Money and Work 2021. Available online: https://www.gcph.co.uk/money_and_work. (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Care Inspectorate. Early Learning and Childcare: Delivering High Quality Play and Learning Environments Outdoors; Communications: Dundee, Scotland, 2018; Available online: https://www.careinspectorate.com/index.php/news/4681-early-learning-and-childcare-practice-note (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, P.C. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pirracchio, R.; Resche-Rigon, M.; Chevret, S. Evaluation of the Propensity score methods for estimating marginal odds ratios in case of small sample size. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, C.; Finch, T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: An outline of normalization process theory. Sociology 2009, 43, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, E.; Treweek, S.; Pope, C.; MacFarlane, A.; Ballini, L.; Dowrick, C.; Finch, T.; Kennedy, A.; Mair, F.; O’Donnell, C.; et al. Normalisation process theory: A framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med. 2010, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- May, C.R.; Cummings, A.; Girling, M.; Bracher, M.; Mair, F.S.; May, C.M.; Murray, E.; Myall, M.; Rapley, T.; Finch, T. Using Normalization Process Theory in feasibility studies and process evaluations of complex healthcare interventions: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, S.M.; Chan, C.L.; Campbell, M.J.; Bond, C.M.; Hopewell, S.; Thabane, L.; Lancaster, G.A. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016, 355, i5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hallingberg, B.; Turley, R.; Segrott, J.; Wight, D.; Craig, P.; Moore, L.; Murphy, S.; Robling, M.; Simpson, S.A.; Moore, G. Exploratory studies to decide whether and how to proceed with full-scale evaluations of public health interventions: A systematic review of guidance. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018, 4, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, N.; Naylor, P.J.; Ashe, M.C.; Fernandez, M.; Yoong, S.L.; Wolfenden, L. Guidance for conducting feasibility and pilot studies for implementation trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2020, 6, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/collections/scottish-index-of-multiple-deprivation-2020/ (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Sun, S.H.; Zhu, Y.C.; Shih, C.L.; Lin, C.H.; Wu, S.K. Development and initial validation of the Preschooler Gross Motor Quality Scale. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2010, 31, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. The strength and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theunissen, M.H.; Vogels, A.G.; de Wolff, M.S.; Crone, M.R.; Reijneveld, S.A. Comparing three short questionnaires to detect psychosocial problems among 3 to 4-year olds. BMC Pediatrics 2015, 15, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Branje, K.; Stevens, D.; Hobson, H.; Kirk, S.; Stone, M. Impact of an outdoor loose parts intervention on Nova Scotia preschoolers’ fundamental movement skills: A multi-methods randomized controlled trial. AIMS Public Health 2021, 9, 194–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, S.J.; Noonan, R.; Rowlands, A.V.; Van Hees, V.; Knowles, Z.R.; Boddy, L.M. Wear compliance and activity in children wearing wrist- and hip-mounted accelerometers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Liu, W.; McDonough, D.J.; Zeng, N.; Lee, J.E. The Dilemma of Analyzing Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior with Wrist Accelerometer Data: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeger-Aschmann, C.S.; Schmutz, E.A.; Zysset, A.E.; Kakebeeke, T.H.; Messerli-Bürgy, N.; Stülb, K.; Arhab, A.; Meyer, A.H.; Munsch, S.; Jenni, O.G.; et al. Accelerometer-derived physical activity estimation in preschoolers—Comparison of cut-point sets incorporating the vector magnitude vs. the vertical axis. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenburg, T.M.; de Vries, L.; op den Buijsch, R.; Eyre, E.; Dobell, A.; Duncan, M.; Chinapaw, M.J. Cross-validation of cut-points in preschool children using different accelerometer placements and data axes. J. Sports Sci. 2022, 40, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Craemer, M.; Decraene, M.; Willems, I.; Buysse, F.; Van Driessche, E.; Verbestel, V. Objective measurement of 24-h movement behaviors in preschool children using wrist-worn and thigh-worn accelerometers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migueles, J.H.; Cadenas-Sanchez, C.; Ekelund, U.; Delisle Nyström, C.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Löf, M.; Labayen, I.; Ruiz, J.R.; Ortega, F.B. Accelerometer Data Collection and Processing Criteria to Assess Physical Activity and Other Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Practical Considerations. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1821–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, E.; Ekelund, U.; Nero, H.; Marcus, C.; Hagströmer, M. Calibration and cross-validation of a wrist-worn Actigraph in young preschoolers. Pediatr. Obes. 2015, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hislop, J.; Palmer, N.; Anand, P.; Aldin, T. Validity of wrist worn accelerometers and comparability between hip and wrist placement sites in estimating physical activity behaviour in preschool children. Physiol. Meas. 2016, 37, 1701–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Axivity. AX3 User Manual; Axivity Ltd.: Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 2015; Available online: https://axivity.com/userguides/ax3/settings/ (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Van Hees, V.T.; Sabia, S.; Jones, S.E.; Wood, A.R.; Anderson, K.N.; Kivimäki, M.; Frayling, T.M.; Pack, A.I.; Bucan, M.; Trenell, M.I.; et al. Estimating sleep parameters using an accelerometer without sleep diary. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyall, L.M.; Sangha, N.; Wyse, C.; Hindle, E.; Haughton, D.; Campbell, K.; Brown, J.; Moore, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Inchley, J.C.; et al. Accelerometry-assessed sleep duration and timing in late childhood and adolescence in Scottish schoolchildren: A feasibility study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lewis, M.; Bromley, K.; Sutton, C.J.; McCray, G.; Myers, H.L.; Lancaster, G.A. Determining sample size for progression criteria for pragmatic pilot RCTs: The hypothesis test strikes back! Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heft, H. Affordances and the Body: An Intentional Analysis of Gibson’s Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 1989, 19, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Question | Criteria (How We Know We Have Achieved Objective) and Information Required | Data Collection Tools | Procedures | Study Population | Analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. To what extent are the intended participants recruited to the study and retained? | Data collected on eligible ELC settings, number that consent to take part, do not consent, and do not respond. Demographic characteristics, number that are retained or lost at follow-up | A map of ELC settings in GCC area will be used to identify eligible ELC settings. Email will be used for expression of interest. Setting demographics will be acquired via questionnaire. Parents will receive parent information sheet (PIS), consent form, and demographic characteristics questionnaire. | OT will approach eligible ELC settings via email with PIS, consent form, and letter of agreement, and a request for languages spoken at the nursery. These will be signed and returned if settings wish to take part. Flyers with QR codes will be distributed to parents. QR codes will give parents access to PIS, consent form, and surveys. Paper copies will also be available. The number of children who consent, do not consent, and do not respond will be recorded based on the number of returned consent forms. The number of retained participants and ELC settings will be recorded based on the number still participating at follow-up | Participating ELC settings in Glasgow and the children and staff attending them. | Calculate the number of consenting participants as a percentage of the total eligible ELC settings and children. |

| 2. To what extent can propensity score matching based on multiple treatment groups be suitably applied within this context? | Data collected on number of children successfully matched across all participating ELC settings. | Children’s demographic information used for matching. | Observed covariates are recorded in both groups. A propensity score is calculated based on these characteristics. Propensity score of children in fully outdoor settings and satellite settings will be matched with propensity score of children in traditional ELC settings. The difference in average outcomes of the matched pairs are compared and a local average treatment effect is estimated. To reduce the risk of bias, matching will be combined with difference-in-differences method, facilitates correction of differences between groups that are fixed over time (reduces the risk of bias in the estimation). | Participating children in all participating ELC settings in Glasgow. | Average treatment effect will be calculated based on the propensity scoring matching of participants from each group. |

| 3. What outcomes should be included in a future impact evaluation and how should they be measured? | Data collected on outcome measurements using, device worn measurements, questionnaires, and observations. Completeness of data collected and ease of use regarding measurement tools. Which outcome measurement tools identify a change in effect from baseline to follow-up (positive, negative, or null)? | Weight and height: portable standiometer and digital scales. Motor competence: Preschool Gross Motor Quality Scale (PGMQS)PA and sleep: Axivity device. Social and emotional outcomes: strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Play: Tool for Observing Play Outdoors (TOPO). Semi-structured interviews. | Baseline: weight and height, PGMQS, Axivity (7 days with a minimum of 3 full consecutive days), SDQ. TOPO will be implemented during exposure period. Follow-up: weight & height, PGMQS, SDQ, Axivity. Semi-structured interviews with managers and practitioners. Parents will be given a questionnaire at the end of the study asking how the SDQ and Axivity measurement tools were received. | Participating ELC settings in Glasgow, children, staff, and parents/carers. | Summary statistics will be presented for the outcome measures, means and standard deviations will be presented. |

| 4. To what extent are current monitoing and evaluation (M&E) tools used within, and standardised across, ELC settings? | Monitoring and evaluation tools currently used at participating ELC settings will be examined to determine whether they can support measurement of outcomes and if analysis can be standardised across settings. | Learning journals (see-saw) | A sample of journals from each participating ELC setting (journals of participating children) will be collected and analysed for similar themes (e.g., are the same outcomes recorded, how often is information recorded in the journals, does the same practitioner record for the same child each time). | Participating ELC settings and participating (consent) children. | Thematic analysis to determine with a standardised framework can be developed for analysing journals to support outcome monitoring in a full-scale evaluation. |

| 5. To what extent is the programme acceptable to ELC managers and practitioners? | Acceptability of programme implementation. | Semi-structured interviews with ELC managers and practitioners. | Purposive sample of managers and practitioners will be invited to interview, consent obtained, interviews recorded and transcribed. | Participating ELC settings, managers, and practitioners. | Qualitative interviews will be thematically analysed. |

| 6. To what extent is the study design acceptable to ELC managers and practitioners? | Acceptability of trial methods including recruitment process and data collection methods. | Semi-structured interviews with ELC managers and practitioners. | Purposive sample of managers and practitioners will be invited to interview, consent obtained, interviews recorded and transcribed. | Participating ELC settings, managers, and practitioners. | Qualitative interviews will be thematically analysed. |

| Participant | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| ELC settings |

|

|

| Children |

|

|

| ELC educators |

|

|

| Feasibility and Pilot Study Criteria for Progression to a Powered Effectiveness Evaluation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research Question | Traffic light progression criteria | Recommendation if Green, Amber, or Red | Method of assessment | Rationale |

| 1. To what extent are the intended participants recruited to the study and are they retained? | Recruitment: ELC Settings GREEN: at least 30% of contacted ELC settings express a willingness to participate. AMBER: 10 to 29%. RED: less than 10% of contacted ELC settings respond. Participants GREEN: fully outdoor ELC settings, at least 50% of eligible children return a signed consent form. At satellite and traditional ELC settings, at least 25% of eligible children return a signed consent form. AMBER: at least 50% of fully outdoor ELC settings achieve their 50% recruitment target. At least 50% of satellite and traditional ELC settings achieve their 25% recruitment target RED: Amber target is not achieved | GREEN: Strong indication to use the same recruitment process in full effectiveness evaluation. AMBER: Indication that recruitment process might work, but should be discussed with research steering group. RED: Indication that recruitment process needs serious revision before full effectiveness evaluation. | Data collected on eligible ELC settings and participants, response rates, and non-response rates. | Based on recruitment and retention rates of past feasibility studies in UK early years settings (Barber et al., 2019; Kipping et al., 2019; Malden et al., 2019). |

| Retention GREEN: 80% or more participant retention rate. AMBER: 50–79% participant retention rate. RED: less than 50% participant retention rate. | GREEN: Strong indication to use the same recruitment process in full effectiveness evaluation. AMBER: Indication that recruitment process might work, but should be discussed with research steering group. RED: Indication that recruitment process needs revision before full effectiveness evaluation. | |||

| 2. To what extent can propensity score matching based on multiple treatment groups be suitably applied within this context? | GREEN: 80% or more enrolled children suitably matched based on propensity scores. AMBER: 50–79% enrolled children matched. RED: less than 50% enrolled children matched. | GREEN: Strong indication that matching children based on their propensity score is a reliable comparison method to be used in a powered effectiveness evaluation. AMBER: Indication that the matching method might work in an effectiveness evaluation; however, it should be considered alongside other criteria such as the level of missing data. RED: The study design method needs careful consideration before being used again. | Determine the suitability of the covariates collected in the demographic survey are sufficient to calculate reliable propensity scores for matching. | We consider 80% to be achievable if the criteria regarding retention in RQ1 is successful. |

| 3. What outcomes should be included in a future impact evaluation and how should they be measured? | GREEN: 70% or more measures are returned fully completed at baseline and follow-up. Outcome measures are able to identify a change from baseline to follow-up and a difference in effect between intervention and comparison groups (positive or negative). No major acceptability issues during educator interviews or via parent feedback. AMBER: Outcome measure completion rate of 60% or more. An indication that there may be a difference in effect but insufficient data to determine definitively. Three or four major acceptability issues raised by interviewees or through parent feedback; however, mitigating strategy identified. RED: Less than 60% of outcome measures completed. Major acceptability issues raised regarding measurement methods with no possible mitigation strategy. | GREEN: Strong indication to proceed with the outcome measurement methods. AMBER: Medium indication to proceed. Recommend discussing the measurement methods with research steering group. RED: Indication of doubt as to whether to proceed. Measurement methods should be discussed with steering group, taking into consideration findings from RQ6 and whether different measurement tools might be better suited to detect an effect in outcomes. | Baseline and follow-up outcome measures. Feedback from parents in activity diary. Process evaluation interviews with ELC educators. | We consider 70% completion rate sufficient to carry out analysis. |

| 4. To what extent are current M&E tools used within, and standardised across, ELC settings? | GREEN: a standardised method of analysing M&E tools across ELC settings is identified and can be used for measuring specific outcomes in a powered effectiveness evaluation. AMBER: there is the potential to standardise the analysis of M&E tools across settings that would require minor changes within ELC practice. RED: there is considerable variation between ELC settings regarding the recording methods of outcomes and adapting practice would be counterproductive. | GREEN: Strong indication to proceed with M&E practices that are already in place to record and analyse some outcomes. AMBER: Medium indication to proceed. Recommend discussing the M&E methods with steering group and making a judgement on how to proceed. RED: Not likely to be an effective use of time or resources. Judgement as to how to proceed should be considered with steering group. | A sample of M&E practices from participating children at enrolled ELC settings. | Standardising the analysis of M&E practices already in place at ELC settings will reduce the burden on participating ELC settings in the next stage of evaluation. |

| 5. To what extent is the programme acceptable to ELC managers and practitioners? | GREEN: analysis of interviews identify little (minor) to no barriers mentioned on supporting the provision of outdoor play and learning within the constructs of the Normalisation Process Theory. AMBER: three or four modifiable barriers identified within the constructs of NPT. RED: several major and non-modifiable barriers identified regarding the acceptability of outdoor play and learning among interviewed participants within the constructs of NPT. | GREEN: Strong indication that outdoor play and learning is becoming a normal practice for ELC practitioners and evaluation of the programme can proceed. AMBER: Indication that outdoor play and learning provision is not yet a normal practice across ELC settings. Findings should be considered with research steering group before proceeding with next stage of evaluation. RED: Doubt regarding whether outdoor play and learning provision is considered a normal practice among ELC practitioners and managers. Steering group should be consulted regarding whether knowledge of outdoor play and learning needs to be promoted among ELC educators before proceeding to an evaluation (e.g., education intervention). | Acceptability of the programme will be assessed through interviews with ELC headteachers/managers and practitioners using the four constructs of NPT (Coherence, Cognitive Participation, Collective Action, Reflexive Monitoring) as part of the process evaluation. See Appendix A for the interview guide. | A focus on major issues associated with the constructs of NPT is considered acceptable for qualitative data rather than quantitative targets. |

| 6. To what extent is the study design acceptable to ELC managers and practitioners? | GREEN: analysis of interview data identifies little (minor) to no barriers on supporting the study design within the constructs of the NPT. AMBER: three or four modifiable barriers identified within the constructs of NPT. RED: several major and non-modifiable barriers identified regarding the acceptability of the study design among interviewed participants within the constructs of NPT. | GREEN: Strong indication that the study design methods are acceptable among early years educators and children and can be taken forward to a powered effectiveness evaluation. Recommendation as per green target of RQ2. AMBER: Indication that the interview responses should be discussed with the research steering group and a decision made on how the study design can be adapted to be less burdensome. Recommendation as per amber of RQ2. RED: Indication that study design is too labour intensive for participants and needs to be revised before progression to next stage of the evaluation. Recommendation as per red of RQ2. | Acceptability of the study design will be assessed through interviews with ELC headteachers/managers and practitioners using the four constructs of NPT (Coherence, Cognitive Participation, Collective Action, Reflexive Monitoring) as part of the process evaluation. See Appendix A for the interview guide. | A focus on major issues associated with the constructs of NPT is considered acceptable for qualitative data rather than quantitative targets. |

| Participant | Measurement Tool | Data Collection Timepoints at Participating ELC Settings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Week 0) | Mid-Point | Follow-Up (Week 5) | ||

| Child | Parent/carer Demographic Questionnaire | 🗴 | ||

| Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire | 🗴 | 🗴 | ||

| Height and weight | 🗴 | 🗴 | ||

| Preschool Gross Motor Quality Scale | 🗴 | 🗴 | ||

| Axivity (physical activity, sedentary time, sleep) | 🗴 | 🗴 | ||

| Headteachers/ practitioners | Play behaviours (TOPO) | 🗴 | 🗴 | |

| Semi-structured interviews | 🗴 | |||

| ELC Monitoring and evaluation tools | 🗴 | |||

| Task Code | Balance Task | Criterion Code |

|---|---|---|

| B1 | Single leg standing |

|

| B2 | Tandem standing |

|

| B3 | Walking line forward |

|

| B4 | Walking line backward |

|

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Play with great heights | Danger of injury from falling from a height relative to the child’s own height such as forms of climbing, jumping, balancing from heights |

| Play with high speed | Uncontrolled speed relative to the child that can lead to a collision with someone (or something) such as on a bicycle, sliding, or running uncontrollably |

| Play with dangerous tools | Tools that can lead to injuries such as knives, hammers, or ropes |

| Play near dangerous elements | Such as a body of water or fire pit |

| Rough-and-tumble play | Where children can harm each other such as wrestling or fencing with sticks |

| Play where children go exploring alone | With the possibility of getting lost such as without supervision and where there are no boundaries or barriers |

| Play with impact | Children crashing into something repeatedly for fun |

| Vicarious play | Children getting excited from watching others engaging in risk |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Traynor, O.; McCrorie, P.; Chng, N.R.; Martin, A. Evaluating Outdoor Nature-Based Early Learning and Childcare Provision for Children Aged 3 Years: Protocol of a Feasibility and Pilot Quasi-Experimental Design. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127461

Traynor O, McCrorie P, Chng NR, Martin A. Evaluating Outdoor Nature-Based Early Learning and Childcare Provision for Children Aged 3 Years: Protocol of a Feasibility and Pilot Quasi-Experimental Design. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(12):7461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127461

Chicago/Turabian StyleTraynor, Oliver, Paul McCrorie, Nai Rui Chng, and Anne Martin. 2022. "Evaluating Outdoor Nature-Based Early Learning and Childcare Provision for Children Aged 3 Years: Protocol of a Feasibility and Pilot Quasi-Experimental Design" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 12: 7461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127461

APA StyleTraynor, O., McCrorie, P., Chng, N. R., & Martin, A. (2022). Evaluating Outdoor Nature-Based Early Learning and Childcare Provision for Children Aged 3 Years: Protocol of a Feasibility and Pilot Quasi-Experimental Design. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127461