The Forgotten Age Phase of Healthy Lifestyle Promotion? A Preliminary Study to Examine the Potential Call for Targeted Physical Activity and Nutrition Education for Older Adolescents

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context

2.2. Participants and Their Schools

2.3. Online Questionnaire and Ethical Considerations

2.4. Data Analysis

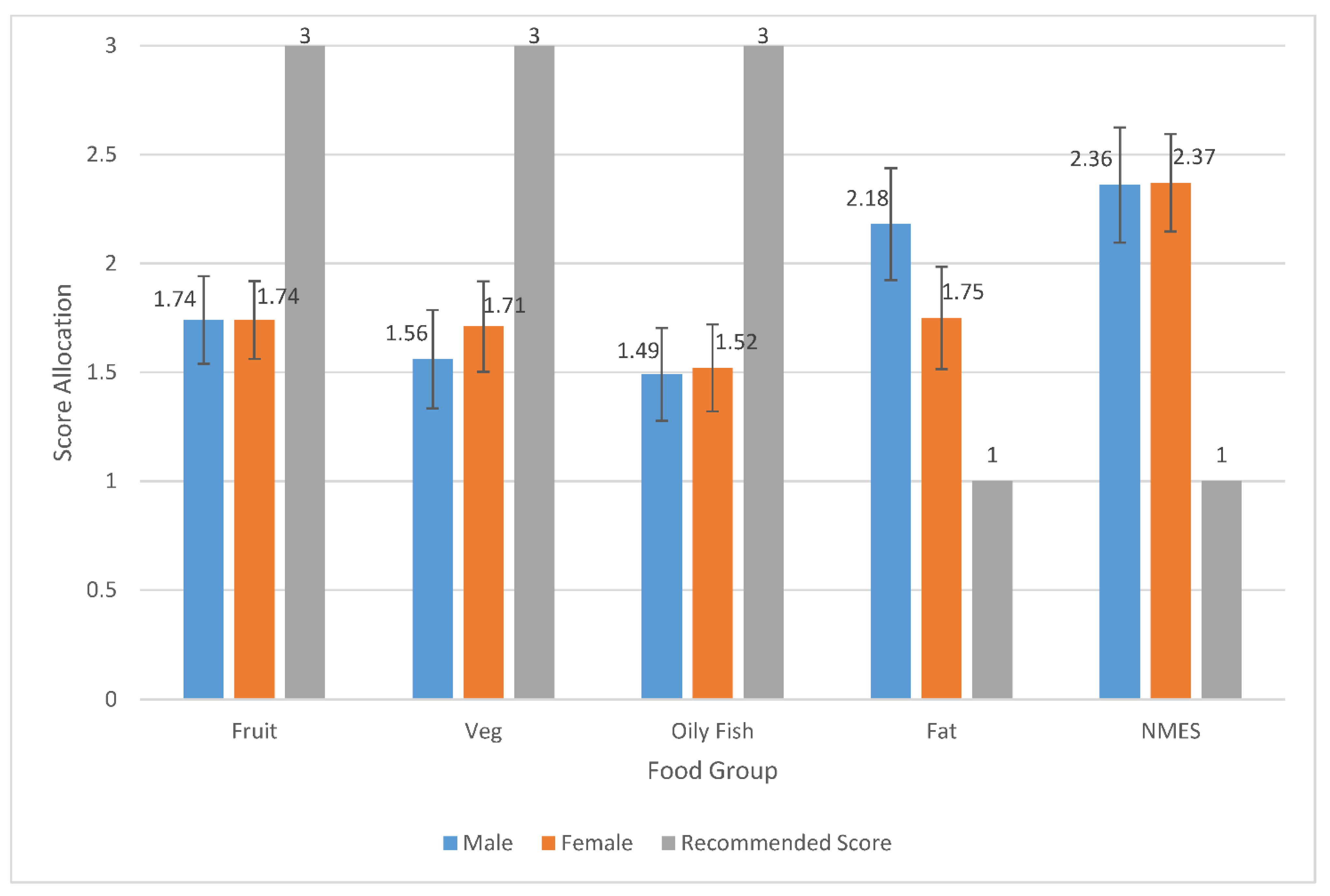

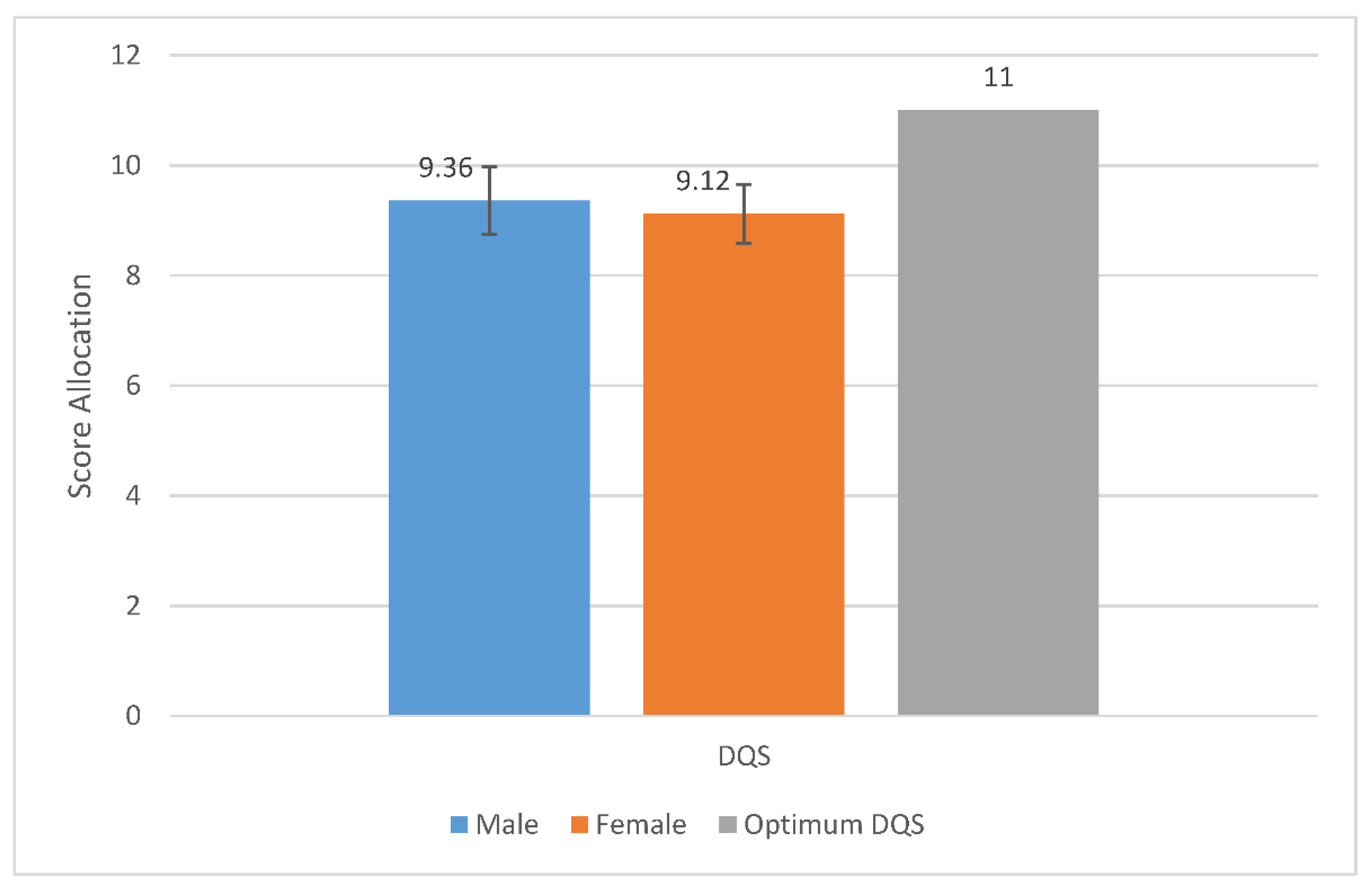

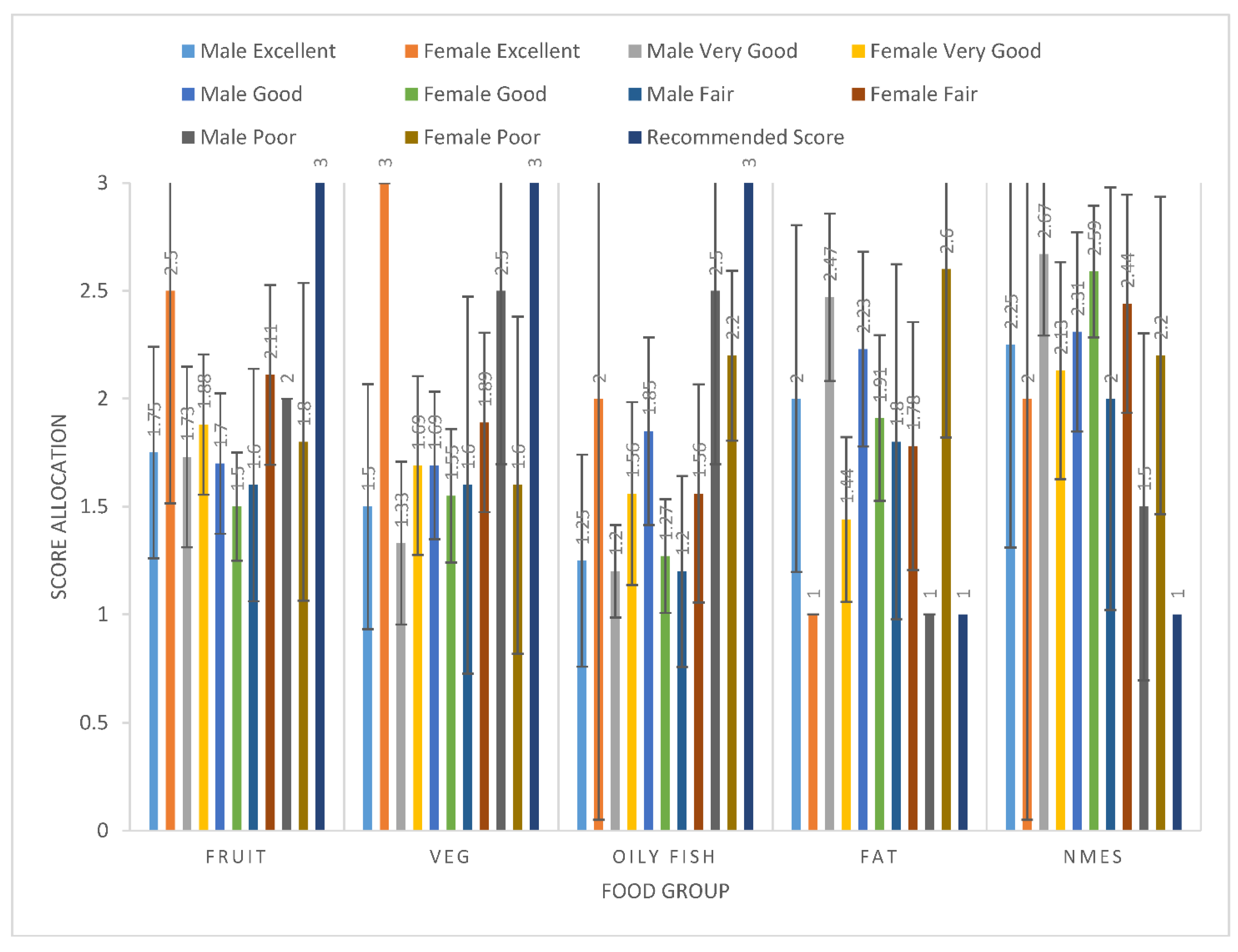

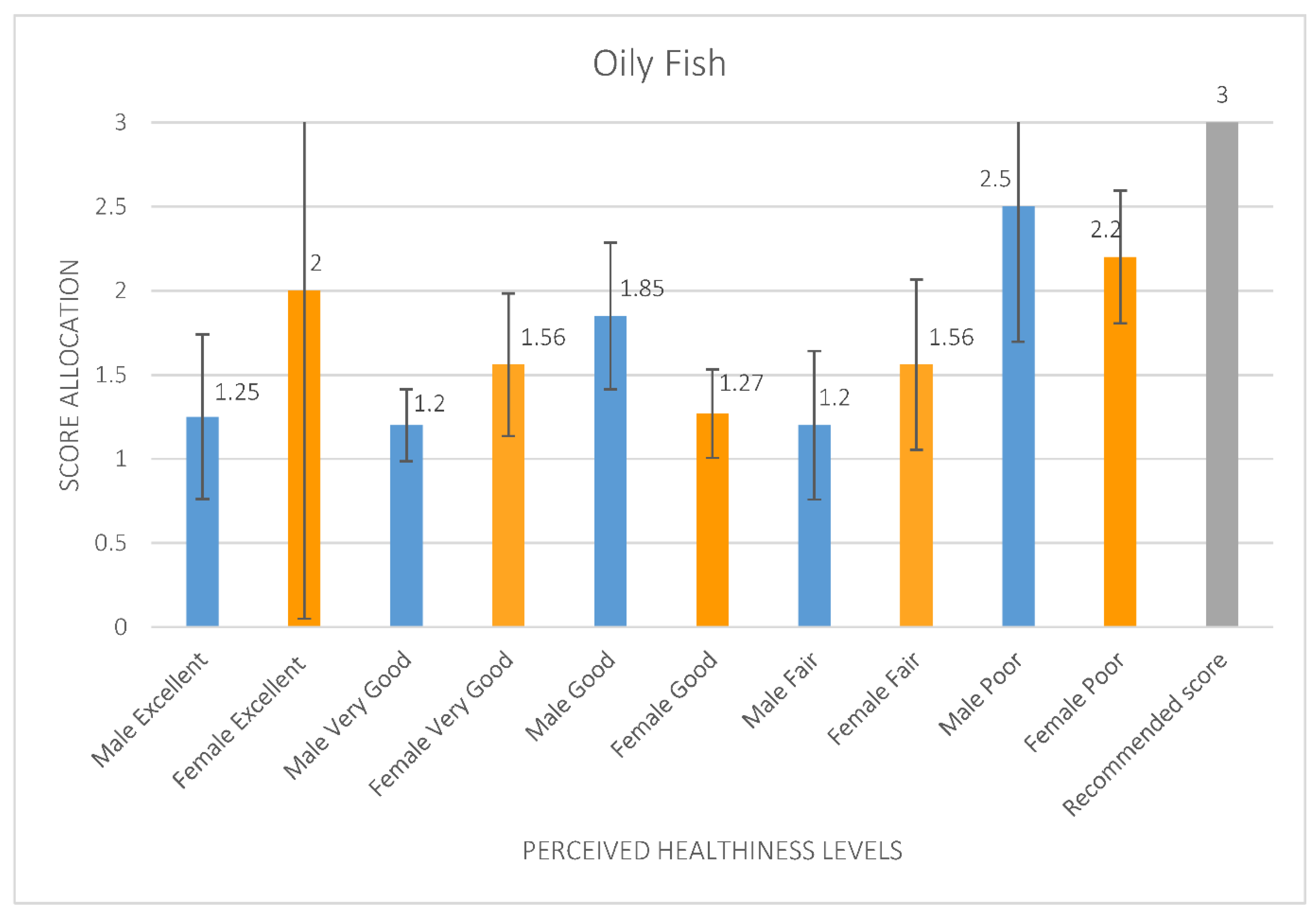

3. Results

3.1. Physical Activity and Sedentary Time

3.2. Promotion of Healthy Lifestyles

4. Discussion

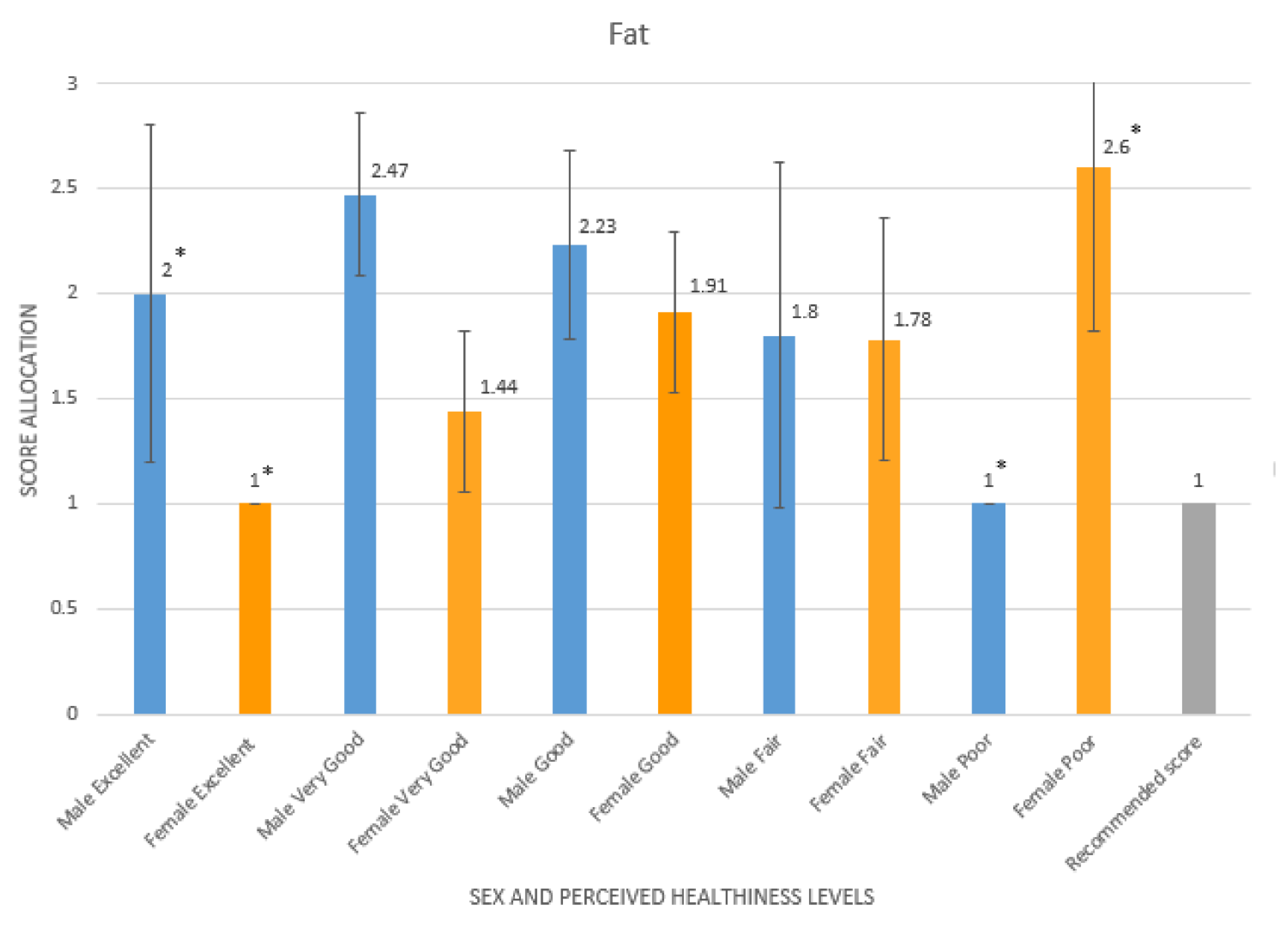

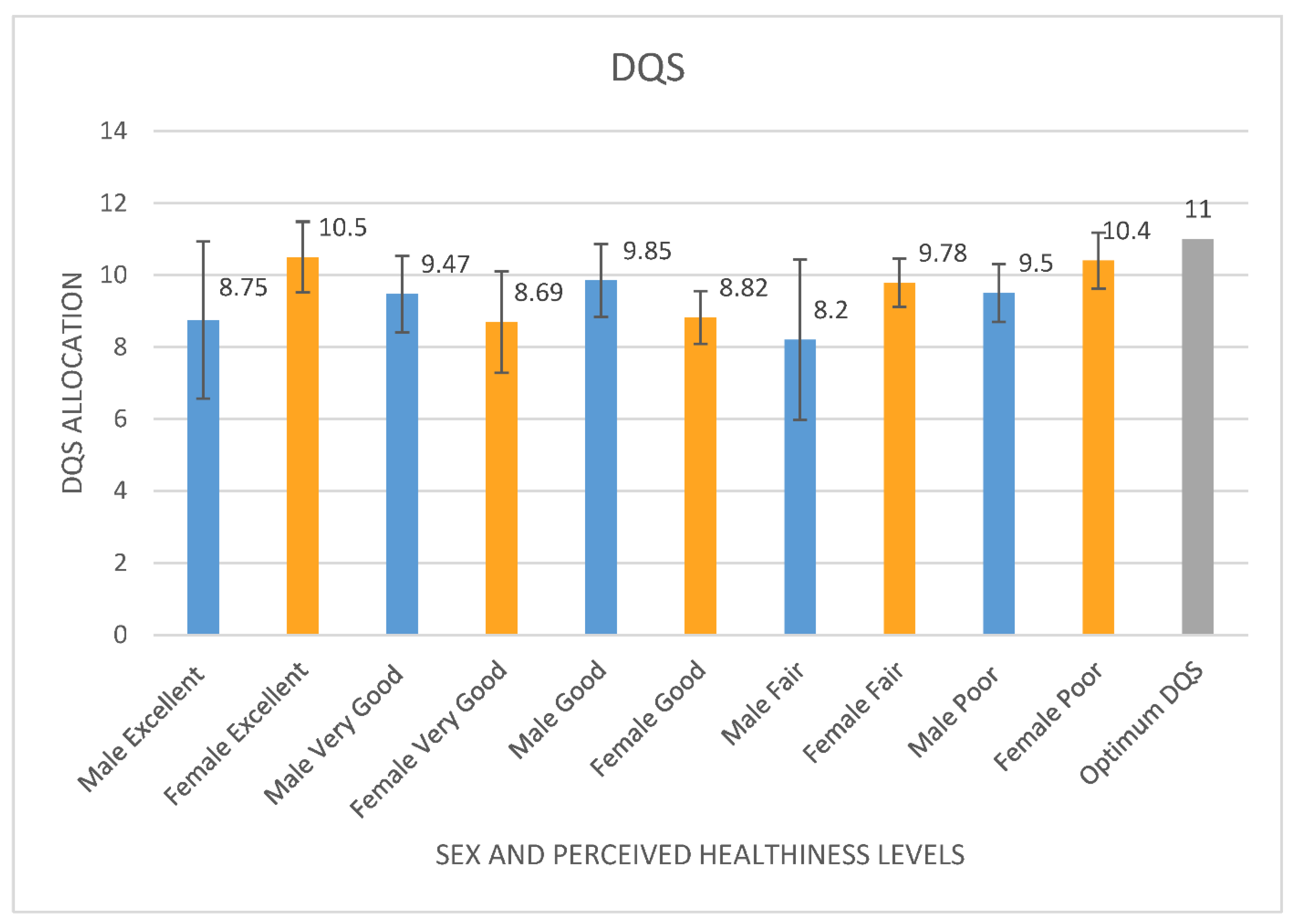

4.1. Food Frequencies

4.2. Physical Activity

4.3. Promoting Healthy Lifestyles

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Viner, R.; Macfarlane, A. Health promotion. Br. Med. J. 2005, 330, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tylee, A.; Haller, D.M.; Graham, T.; Churchill, R.; Sanci, L.A. Youth-friendly primary-care services: How are we doing and what more needs to be done? Lancet 2007, 369, 1565–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Europe. “Nothing About Us, without Us” Tips for Policy Makers on Child and Adolescent Participation in Policy Development; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education (DfE). Relationships Education, Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education. Statutory Guidance for Governing Bodies, Priorietors, Head Teachers, Principals, Senior Leadership Teams, Teachers; Crown Copyright: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.W.; Begoray, D.; MacDonald, M. A Social Ecological Conceptual Framework for Understanding Adolescent Health Literacy in the Health Education Classroom. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2009, 44, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.; Wells, R.; Hawkes, C. How Primary School Curriculums in 11 Countries around the World Deliver Food Education and Address Food Literacy: A Policy Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department for Education (DfE). Design and Technology Programmes of Study: Key Stages 1 and 2; National curriculum in England; Crown Copyright: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, N.D.; Davis, T.C.; McCormack, L. Health Literacy: What Is It? J. Health Commun. 2010, 15 (Suppl. S2), 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutbeam, D. Defining and measuring health literacy: What can we learn from literacy studies? Int. J. Public Health 2009, 54, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van der Heide, I.; Wang, J.; Droomers, M.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Rademakers, J.; Uiters, E. The relationship between health, education, and health literacy: Results from the Dutch Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18 (Suppl. S1), 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Health Service (NHS). Enabling People to Make Informed Health Decisions. 2015. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/patient-participation/health-decisions/ (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Schulenkorf, T.; Sørensen, K.; Okan, O. International Understandings of Health Literacy in Childhood and Adolescence—A Qualitative Explorative Analysis of Global Expert Interviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 2072–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröder, J.; Okan, O.; Bauer, U.; Bruland, D.; Schlupp, S.; Bollweg, T.M.; Saboga-Nunes, L.; Bond, E.; Sørensen, K.; Bitzer, E.M.; et al. Health literacy in childhood and youth: A systematic review of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinert, S. Adolescent health: An opportunity not to be missed. Lancet 2007, 369, 1057–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.S.; Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Danaei, G.; Shibuya, K.; Adair-Rohani, H.; AlMazroa, M.A.; Amann, M.; Anderson, H.R.; Andrews, K.G.; et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2224–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, G.; Bao, W.; Hu, F.B. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2014, 349, g4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Public Health England. National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Results from Years 5 and 6 (Combined) of the Rolling Programme (2012/2013–2013/2014); Public Health England: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Europe. Adolescents Taking the Lead. Multistakeholder Consultation to Promote Adolescent Well-Being in the WHO European Region; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M.; Toporov, E.; Himes, J.H.; Resnick, M.D.; Blum, R.W. Covariations of eating behaviors with other health-related behaviors among adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 1997, 20, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, R.A.; Burke, V.; Dunbar, D.L.; Spencer, M.; Balde, E.; Beilin, L.J.; Gracey, M.P. Associations between lifestyle and cardiovascular risk factors in 18-year-old Australians. J. Adolesc. Health 1997, 21, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senderowitz, J. Adolescent Health: Reassessing the Passage to Adulthood; World Bank Discussion Paper No. 272; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jessiman, P.E.; Campbell, R.; Jago RVan Sluijs, E.M.F.; Newbury-Birch, D. A qualitative study of health promotion in academy schools in England. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for National Statistics. Census for England and Wales; Office for National Statistics: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education (DfE) National Statistics. Schools, Pupils and Their Characteristics: January 2019; National Statistics. Information Policy Team, The National Archives; Crown Copyright: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Healthy Schools Initiative. Physical Activity Guidance Documents; NHS and Department for Children, Schools and Families; Crown Copyright: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England. Government Dietary Recommendations. Government Recommendations for Energy and Nutrients for Males and Females 1—18 Years and 19+ Year; Crown Copyright: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cleghorn, C.; Cade, J. Short Form Food Frequency Questionnaire. 2017. Available online: https://www.nutritools.org/tools/136#t1 (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Bull, F.C.; Maslin, T.S.; Armstrong, T. Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ) nine country reliability and validity study. J. Phys. Act. Health. 2009, 6, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wanner, M.; Hartmann, C.; Pestoni, G.; Winfried Martin, B.; Siegrist, M.; Martin-Diener, E. Validation of the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire for self-administration in a European context. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2017, 3, e000206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cleghorn, C.; Harrison, R.A.; Ransley, J.K.; Wilkinson, S.; Thomas, J.; Cade, J.E. Can a dietary quality score derived from a short-form FFQ assess dietary quality in UK adult population survey? Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 2915–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases; Technical Report Series 916; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, K.E.; Latin, R.W. Essentials of Research Methods in Health, PE, Exercise Science and Recreation, 3rd ed.; Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol. 2. Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) Analysis Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eldh, A.C.; Årestedt, L.; Berterö, C. Quotations in Qualitative Studies: Reflections on Constituents, Customs and Purpose. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, T.; Morris, S.S.; Tumilowicz, A. Global Patterns of Adolescent Fruit, Vegetable, Carbonated Soft Drink, and Fast-Food Consumption: A Meta-Analysis of Global School-Based Student Health Surveys. Food Nutr. Bull. 2019, 40, 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Implementing Effective Actions for Improving Adolescent Nutrition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Park, A.; Eckert, T.L.; Zaso, M.J.; Scott-Sheldon, L.A.J.; Vanable, P.A.; Carey, K.B.; Ewart, C.K.; Carey, M.P. Associations Between Health Literacy and Health Behaviors Among Urban High School Students. J. Sch. Health 2017, 87, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corfe, S. What Are the Barriers to Eating Healthily in the UK? Social Market Foundation: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Giacobone, G.; Tiscornia, M.V.; Guarnieri, L.; Castronuovo, L.; Mackay, S.; Allemandi, L. Measuring cost and affordability of current vs. healthy diets in Argentina: An application of linear programming and the INFORMAS protocol. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UK Chief Medical Officers. Physical Activity Guidelines. 2019. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1054282/physical-activity-for-children-and-young-people-5-to-18-years.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Sluijs, E.M.; Ekelund, U.; Crochemore-Silva, I.; Guthold, R.; Ha, A.; Lubans, D.; Oyeyemi ALDing, D.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Physical activity behaviours in adolescence: Current evidence and opportunities for intervention. Lancet 2021, 398, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet (2021) Physical Activity 2021 Executive Summary. 2021. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/series/physical-activity-2021 (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- World Health Organization Europe. 85% of Adolescent Gilrs Don’t Do Enough Physical Activity: A New WHO Study Calls for Action. 2022. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/physical-activity/news/news/2022/3/85-of-adolescent-girls-dont-do-enough-physical-activity-new-who-study-calls-for-action (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Rose, T.; Barker, M.; Jacob, C.; Morrison, L.; Lawrence, W.; Strömmer, S.; Vogel, C.; Woods-Townsend, K.; Farrel, D.; Inskip, H.; et al. A Systematic Review of Digital Interventions for Improving the Diet and Physical Activity Behaviors of Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peters, R.; Ee, N.; Peters, J.; Beckett, N.; Booth, A.; Rockwood, K.; Anstey, K.J. Common risk factors for major noncommunicable disease, a systematic overview of reviews and commentary: The implied potential for targeted risk reduction. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2019, 10, 2040622319880392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization Europe. WHO/Europe Urges Government to Include Young People in Decisions about Their Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/Life-stages/child-and-adolescent-health/news/news/2022/2/whoeurope-urges-governments-to-include-young-people-in-decisions-about-their-health (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- LaRouche, R.; Saunders, T.J.; Faulkner, G.; Colley, R.; Tremblay, M. Associations between active school transport and physical activity, body composition, and cardiovascular fitness: A systematic review of 68 studies. J. Phys. Act. Health 2014, 11, 206–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, S.A.; Aubert, S.; Barnes, J.D.; Larouche, R.; Tremblay, M.S. Profiles of Active Transportation among Children and Adolescents in the Global Matrix 3.0 Initiative: A 49-Country Comparison. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standage, M.; Sherar, L.; Curran, T.; Wilkie, H.J.; Jago, R.; Davis, A.; Foster, C. Results From England’s 2018 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, S347–S349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RAC. Driving Test Backlog Leaves Learners Facing 10-Month Wait. 2022. Available online: https://www.rac.co.uk/drive/news/infrastructure/driving-test-backlog-leaves-learners-facing-10-month-wait/ (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- World Health Organization. Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!) Guidance to Support Country Implementation. 2017. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255415/9789241512343-eng.pdf;jsessionid=7E005BA31D28787F81D706BFEBCD827F?sequence=1 (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Griffin, T.L.; Jackson, D.M.; McNeill, G.; Aucott, L.S.; Macdiarmid, J.I. A Brief Educational Intervention Increases Knowledge of the Sugar Content of Foods and Drinks but Does Not Decrease Intakes in Scottish Children Aged 10-12 Years. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upton, P.; Taylor, C.; Upton, D. The effects of the Food Dudes Programme on children’s intake of unhealthy foods at lunchtime. Perspect Public Health 2015, 135, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Telama, R. Tracking of physical activity from childhood to adulthood: A review. Obes. Facts. 2009, 2, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracey, D.; Stanley, N.; Burke, V.; Corti, B.; Beilin, L.J. Nutritional knowledge, beliefs and behaviour in teenage school students. Health Educ. Res. 1996, 11, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaterlaus, J.M.; Patten, E.V.; Roche, C.; You-ng, J.A. #Gettinghealthy: The perceived influence of social media on young adults health behaviours. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaisime, M.; Robertson-James, C.; Mejia, L.; Núñez, A.; Wolf, J.; Reels, S. Social Media and Teens: A Needs Assessment Exploring the Potential Role of Social Media in Promoting Health. Soc. Media Soc. 2020, 6, 2056305119886025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin-Zamier, D.; Lemish, D.; Gofin, R. Media Health Literacy (MHL): Development and measurement of the concept among adolescents. Health Educ. Res. 2011, 26, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandelanotte, C.; Kirwan, M.; Rebar, A.; Alley, S.; Short, C.; Fallon, L.; Buzza, G.; Schoeppe, S.; Mahar, C.; Duncan, M.J. Examining the use of evidence-based and social media supported tools in freely accessible physical activity intervention websites. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guse, K.; Levine, D.; Martins, S.; Lira, A.; Gaarde, J.; Westmorland, W.; Gilliam, M. Interventions using new digital media to improve adolescent sexual health: A systematic review. J. Adolesc. Health 2012, 51, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, E.; Aucott, L.; Poobalan, A. Are young adults appreciating the health promotion messages on diet and exercise? Z. Gesundh. 2018, 25, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Giles, E.L.; Brennan, M. Changing the lifestyles of young adults. J. Soc. Mark. 2015, 5, 206–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baker, H.J.; Butler, L.T.; Chambers, S.A.; Traill, W.B.; Lobb, A.E.; Herbert, G. An RCT study to evaluate a targeted, theory driving healthy eating leaflet. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 1916–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.F. Research Methods in Sport; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gorard, S. Quantitative Methods in Educational Research: The Role of Numbers Made Easy; Continuum: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education (DfE). State of the Nation 2020: Children and Young People’s Wellbeing; Research Report; Crown Copyright: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, P.L.; Crouter, S.E.; Bassett, D.R. Pedometer measures of free-living physical activity: Comparison of 13 models. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Food Group | Score Allocated | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Fruit | <=2 servings/wk | >2 servings/wk and <2 servings/day | >=2 servings/day |

| Vegetables | <=1 servings/day | 1–3 servings/day | >=3 servings/day |

| Oily Fish | No intake | 0–200 g/wk | >=200 g/wk |

| Fat | >=1 ½ × UK recommendations (127.5 g/day) | 1–1 ½ × UK recommendations | <=UK recommendations (85 g/day) |

| NMES | >=1 ½ × UK recommendations (90 g/day) | 1–1 ½ × UK recommendations | <=UK recommendations (60 g/day) |

| “They aren’t promoted enough for our age group and no time in school is given to educate us about health or nutrition.” |

| “I’m really sceptical about the healthy lifestyles that I’ve seen, they’re either selling some fake product that’ll burn your fat or try to make you do things that aren’t necessarily right.” |

| “I feel that healthy lifestyles are marketed towards young people my age in a very disillusioning way, as it makes us think we need to spend money to get fit.” |

| ‘I feel I have been left in the dark and left alone’ |

| Healthy lifestyles were promoted to them “as children….but as we’ve gotten older, it’s all stopped”. |

| “It’s presumed we all know how to eat better and be healthy” |

| “Healthy lifestyles are not promoted enough, so I don’t know a lot about my own health and fitness”, |

| “There are no healthy options to eat at school, not even an apple!” |

| “It’s not promoted, and it is hard to do any fitness on top of school or work as I have a 40 min walk to and from school and this leaves me drained” |

| “Not very well” |

| “Not promoted at all for our age group” |

| “I want to be able to eat chips and not feel fat” |

| “Unhealthy lifestyles are promoted in the form of size 0 models in magazines” |

| “Only promoted in ways that exacerbates body issues |

| “There is a lack of promotional material about healthy lifestyles of us, we need cheaper gym access.” |

| “Government recommended advice is always shared and schools gives us talks on how we can be healthier” |

| “Commonly promoted on social media” |

| “Promoted well” |

| “Spoken about within Physical Education lessons within school and emphasised repeatedly” |

| “By doctors” |

| “By drilling us with the importance of eating healthy and doing physical activity” |

| “By banning sugary drinks and snacks at school has tried to instil that it’s not good to be eating junk food every day at school” |

| “Via technology e.g. my apple watch” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Howells, K.; Coppinger, T. The Forgotten Age Phase of Healthy Lifestyle Promotion? A Preliminary Study to Examine the Potential Call for Targeted Physical Activity and Nutrition Education for Older Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5970. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105970

Howells K, Coppinger T. The Forgotten Age Phase of Healthy Lifestyle Promotion? A Preliminary Study to Examine the Potential Call for Targeted Physical Activity and Nutrition Education for Older Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(10):5970. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105970

Chicago/Turabian StyleHowells, Kristy, and Tara Coppinger. 2022. "The Forgotten Age Phase of Healthy Lifestyle Promotion? A Preliminary Study to Examine the Potential Call for Targeted Physical Activity and Nutrition Education for Older Adolescents" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 10: 5970. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105970

APA StyleHowells, K., & Coppinger, T. (2022). The Forgotten Age Phase of Healthy Lifestyle Promotion? A Preliminary Study to Examine the Potential Call for Targeted Physical Activity and Nutrition Education for Older Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 5970. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105970