Active Ageing in Italy: A Systematic Review of National and Regional Policies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Active Ageing and Societal Challenges

1.2. International Policy Frameworks

1.3. Aim of the Study

- To understand whether, which and how many AA policies had been designed and implemented at the national and regional level;

- To understand whether Italian AA policies are aligned, and to what extent they are, with key overarching international policy frameworks in order to identify areas of possible improvement.

1.4. The Italian Case

2. Materials and Methods

- The researcher carried out a desk review of policies and documentation publicly available through public web-repositories, literature, media and other channels;

- The researcher asked the main representative(s) at the policy maker’s responsible office for AA (a) to provide the relevant policies and documentation on AA and (b) to organise an interview or group interview with the officers who directly manage or were involved in the implementation and monitoring of AA policies;

- The researcher double-checked and screened the long list of policies and selected only the relevant ones, according to the study conceptual framework and exclusion criteria;

- An interview or group interview was conducted (in-site, or via phone when it was not possible) per each Region/AP in order to get more information and to assess the degree of implementation and proper operation of selected policies;

- The researcher organised all data and findings in a single report, using a common template, with the active contribution of the representatives interviewed.

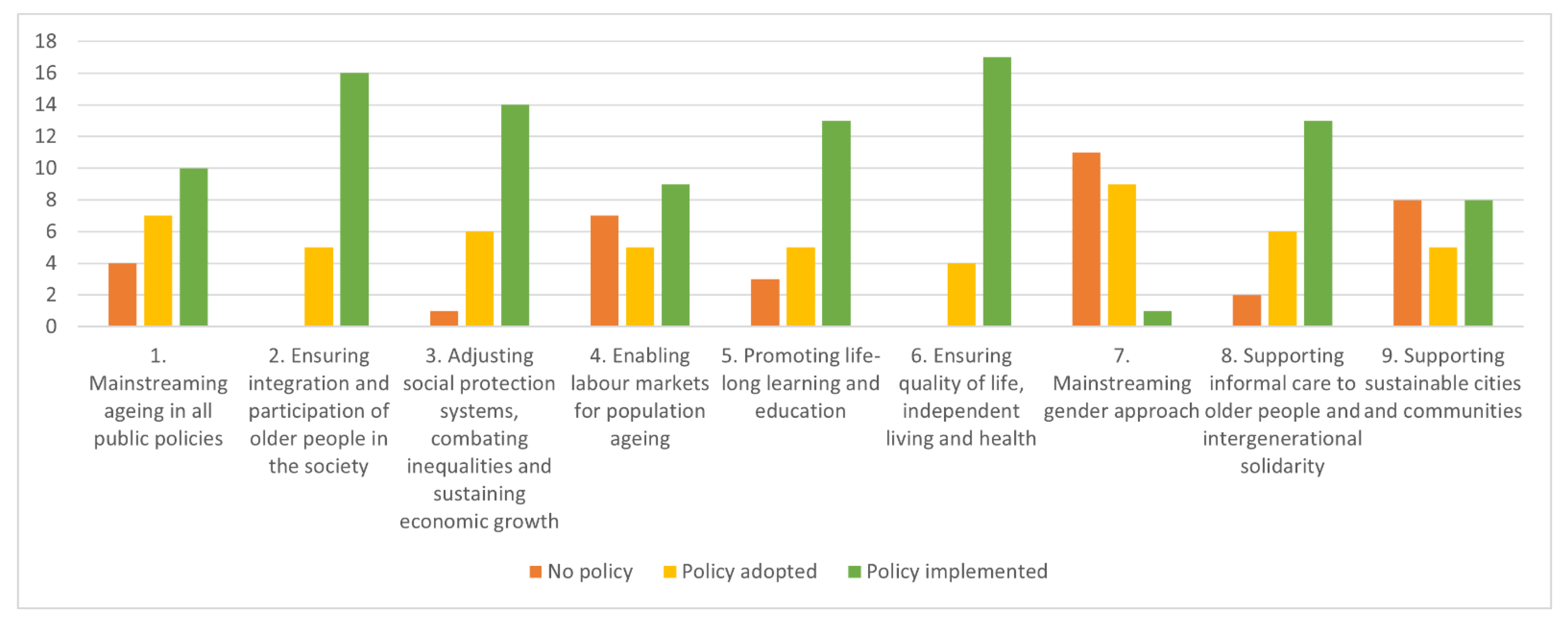

- Mainstreaming ageing in all public policies (MIPAA/RIS 1)

- Ensuring integration and participation of older people in the society (MIPAA/RIS 2, SDG 17, EPSR 19)

- Adjusting social protection systems, combating inequalities and sustaining economic growth (MIPAA/RIS 3, 4, SDG 1, 10, EPSR 3, 12, 13, 14, 15, 20)

- Enabling labour markets for population ageing (MIPAA/RIS 5, SDG 8, EPSR 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

- Promoting life-long learning and education (MIPAA/RIS 6, SDG 4, EPSR 1)

- Ensuring quality of life, independent living and health (MIPAA/RIS 7, SDG 3, EPSR 16, 17, 18)

- Mainstreaming gender approach (MIPAA/RIS 8, SDG 5, EPSR 2)

- Supporting informal care to older people and intergenerational solidarity (MIPAA/RIS 9, SDG 16, EPSR 11)

- Supporting sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11)

3. Results

3.1. Mainstreaming Ageing in All Public Policies

3.1.1. National Level

3.1.2. Regional Level

3.2. Ensuring Integration and Participation of Older People in the Society

3.2.1. National Level

3.2.2. Regional Level

3.3. Adjusting Social Protection Systems, Combating Inequalities and Sustaining Economic Growth

3.3.1. National Level

3.3.2. Regional Level

3.4. Enabling Labour Markets for Population Ageing

3.4.1. National Level

3.4.2. Regional Level

3.5. Promoting Life-Long Learning and Education

3.5.1. National Level

3.5.2. Regional Level

3.6. Ensuring Quality of Life, Independent Living and Health

3.6.1. National Level

3.6.2. Regional level

3.7. Mainstreaming Gender Approach

3.7.1. National Level

3.7.2. Regional Level

3.8. Supporting Informal Care to Older People and Intergenerational Solidarity

3.8.1. National Level

3.8.2. Regional Level

3.9. Supporting Sustainable Cities and Communities

3.9.1. National Level

3.9.2. Regional Level

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Active Ageing: A Policy Framework. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/67215/WHO_NMH_NPH_02.8.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Morrow-Howell, N. Volunteering in later life: Research frontiers. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. 2010, 65, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- A Road Map for European Ageing Research. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eip/ageing/file/314/download_en%3Ftoken=wjqyb0En (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Foster, L.; Walker, A. Active Ageing across the Life Course: Towards a Comprehensive Approach to Prevention. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmel, E.; Hamblin, K.; Papadopoulos, T. Governing the activation of older workers in the European Union: The construction of the “activated retiree”. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2007, 27, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timonen, V. Beyond Successful and Active Ageing: A Theory of Model Ageing; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, L.; Walker, A. Active and successful aging: A European policy perspective. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falanga, R.; Cebulla, A.; Principi, A.; Socci, M. The Participation of Senior Citizens in Policy-Making: Patterning Initiatives in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grenier, A.; Phillipson, C. Precarious Aging: Insecurity and Risk in Late Life. What Makes a Good Life in Late Life? Citizenship and Justice in Aging Societies, special report. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2018, 48, S15–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Standing, G. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class; Bloomsbury Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence; Verso: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Grenier, A.; Phillipson, C.; Laliberte Rudman, D.; Hatzifilalithis, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Marier, P. Precarity in late life: Understanding new forms of risk and insecurity. J. Aging Stud. 2017, 43, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Ageing, Older Persons and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). Political Declaration and Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing; UN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Regional Implementation Strategy for the MIPAA; UNECE: Berlin, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. Council Declaration on the European Year for Active Ageing and Solidarity between Generations: The Way Forward; Council of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Green Paper on Ageing; COM (2021) 50 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. European Pillar of Social Rights; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Agency for Human Rights (FRA). Fundamental Rights Report 2018; FRA: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Age Platform. Assessment of the European Semester 2018; Age Platform: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Age Platform. Social Rights for All Generations: Time to Deliver on the European Pillar of Social Rights; Age Platform: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kucharczyk, M. Social Exclusion in Older-Age and the European Pillar of Social Rights. In Social Exclusion in Later Life; Walsh, K., Scharf, T., Van Regenmortel, S., Wanka, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Resolution 70/1; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bertin, G.; Pantalone, M. Comparing Hybrid Welfare Systems: The Differentiation of Health and Social Care Policies at the Regional Level in Italy. Ital. Sociol. Rev. 2018, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Garavaglia, E.; Lodigliani, R. Active welfare state and active ageing. Inertia, innovations and paradoxes of the Italian case. Transformacje 2013, 3–4, 385–408. [Google Scholar]

- Gualmini, E.; Rizza, R. Attivazione, occupabilità e nuovi orientamenti nelle politiche del lavoro: Il caso italiano e tedesco a confronto [Activation, employability and new directions in labour market policies: A comparison of Italian and German cases]. Stato E Mercato 2011, 92, 195–221. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera, M. The “southern model” of social welfare in Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 1996, 6, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraceno, C. Varieties of familialism: Comparing four southern European and East Asian welfare regimes. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2016, 26, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barbabella, F.; Cela, E.; Di Matteo, C.; Socci, M.; Lamura, G.; Checcucci, P.; Principi, A. New Multilevel Partnerships and Policy Perspectives on Active Ageing in Italy: A National Plan of Action. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Stocktaking on Mainstreaming Ageing in the UNECE Region. Country Note–Italy; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Principi, A.; Di Rosa, M.; Domínguez-Rodríguez, A.; Varlamova, M.; Barbabella, F.; Lamura, G.; Socci, M. The Active Ageing Index and policy-making in Italy. Ageing Soc. 2021, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattrociocchi, L.; Tibaldi, M.; Marsili, M.; Fenga, L.; Caputi, M. Active Ageing and Living Condition of Older Persons Across Italian Regions. J. Popul. Ageing 2020, 14, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principi, A.; Carsughi, A.; Gagliardi, C.; Galassi, F.; Piccinini, F.; Socci, M. Linee Guida di Valenza Regionale in Materia di Invecchiamento Attivo [Regional Guidelines on Active Ageing]; IRCCS INRCA: Ancona, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Principi, A.; Carsughi, A.; Gagliardi, C.; Galassi, F.; Piccinini, F.; Socci, M. Appendice. Schede Leggi e Proposte di Legge su Invecchiamento Attivo [Appendix: Summaries of Laws and Law Proposals on Active Ageing]; IRCCS INRCA: Ancona, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli, U.; Pavolini, E. The Italian Welfare State in a European Perspective: A Comparative Analysis; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barbabella, F.; Principi, A. Le Politiche per L’Invecchiamento Attivo in Italia. Lo Stato Dell’Arte Nelle Regioni, nelle Provincie Autonome, nei Ministeri e nei Dipartimenti Presso la Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri: Raccolta dei Rapporti [Active Ageing Policies in Italy; The State-of-the-Art in Regions, Autonomous Provinces, Ministries and Departments of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers: Collection of Reports]; Dipartimento per le Politiche della Famiglia-IRCCS INRCA: Rome-Ancona, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barbabella, F.; Checcucci, P.; Aversa, M.L.; Scarpetti, G.; Fefè, R.; Socci, M.; Di Matteo, C.; Cela, E.; Damiano, G.; Villa, M.; et al. Le Politiche per L’Invecchiamento Attivo in Italia. Rapporto Sullo Stato Dell’arte [Active Ageing Policies in Italy. State-of-the-Art Report]; Dipartimento per le Politiche della Famiglia-IRCCS INRCA: Rome-Ancona, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weimer, D.L.; Vining, A.R. Policy Analysis: Concepts and Practice, 6th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tonkiss, F. Analysing text and speech: Content and discourse analysis. In Researching Society and Culture; Seale, C., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2004; pp. 368–382. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, R.P. Basic Content Analysis; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zannella, M.; Principi, A.; Lucantoni, D.; Barbabella, F.; Domínguez-Rodríguez, A.; Socci, M. Active ageing: The need to address gender and regional diversity. An evidence-based approach for Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Progetto di Coordinamento Nazionale Partecipato Multilivello delle Politiche Sull’Invecchiamento Attivo. Available online: http://famiglia.governo.it/it/politiche-e-attivita/invecchiamento-attivo/progetto-di-coordinamento-nazionale/ (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Davies, H.T.; Nutley, S.M. What Works? Evidence-Based Policy and Practice in Public Services; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Edelenbos, J. Design and management of participatory public policy making. Public Manag. Int. J. Res. Theory 1999, 1, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucantoni, D.; Checcucci, P.; Socci, M.; Fefè, R.; Lamura, G.; Barbabella, F.; Principi, A. Raccomandazioni per L’Adozione di Politiche in Materia di Invecchiamento Attivo [Recommendations for the Adoption of Active Ageing Policies]; Dipartimento per le Politiche della Famiglia-IRCCS INRCA: Rome-Ancona, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Commitments |

|---|---|

| 1 | To mainstream ageing in all policy fields with the aim of bringing societies and economies into harmony with demographic change to achieve a society for all ages |

| 2 | To ensure full integration and participation of older persons in society |

| 3 | To promote equitable and sustainable economic growth in response to population ageing |

| 4 | To adjust social protection systems in response to demographic changes and their social and economic consequences |

| 5 | To enable labour markets to respond to the economic and social consequences of population ageing |

| 6 | To promote life-long learning and adapt the educational system in order to meet the changing economic, social and demographic conditions |

| 7 | To strive to ensure quality of life at all ages and maintain independent living including health and well-being |

| 8 | To mainstream a gender approach in an ageing society |

| 9 | To support families that provide care for older persons and promote intergenerational and intragenerational solidarity among their members |

| 10 | To promote the implementation and follow-up of the regional implementation strategy through regional co-operation |

| No. | Principles |

|---|---|

| Chapter I: Equal opportunities and access to the labour market | |

| 1 | Education, training and life-long learning |

| 2 | Gender equality |

| 3 | Equal opportunities |

| 4 | Active support to employment |

| Chapter II: Fair working conditions | |

| 5 | Secure and adaptable employment |

| 6 | Wages |

| 7 | Information about employment conditions and protection in case of dismissals |

| 8 | Social dialogue and involvement of workers |

| 9 | Work-life balance |

| 10 | Healthy, safe and well-adapted work environment and data protection |

| Chapter III: Social protection and inclusion | |

| 11 | Childcare and support to children |

| 12 | Social protection |

| 13 | Unemployment benefits |

| 14 | Minimum income |

| 15 | Old age income and pensions |

| 16 | Health care |

| 17 | Inclusion of people with disabilities |

| 18 | Long-term care |

| 19 | Housing and assistance for the homeless |

| 20 | Access to essential services |

| No. | SDGs |

|---|---|

| 1 | End poverty in all its forms everywhere |

| 2 | End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture |

| 3 | Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages |

| 4 | Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all |

| 5 | Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls |

| 6 | Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all |

| 7 | Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all |

| 8 | Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all |

| 9 | Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation |

| 10 | Reduce inequality within and among countries |

| 11 | Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable |

| 12 | Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns |

| 13 | Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts |

| 14 | Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development |

| 15 | Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss |

| 16 | Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels |

| 17 | Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development |

| Ministries | Governmental Offices |

|---|---|

| Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies | Department for Equal Opportunities |

| Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism | Department for Family Policies |

| Ministry of Economic Development | Department for Youth Policies and Universal Civil Service |

| Ministry of Economy and Finances | Governmental Office for Sport |

| Ministry of Education | |

| Ministry of Environment, Land and Sea Protection | |

| Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Co-operation | |

| Ministry of Health | |

| Ministry of Internal Affairs | |

| Ministry of Labour and Social Policies |

| Regions |

|---|

| North-West |

| Piedmont |

| Valle d’Aosta |

| Liguria |

| Lombardy |

| North-East |

| AP of Bolzano |

| AP of Trento |

| Veneto |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia |

| Emilia-Romagna |

| Centre |

| Tuscany |

| Umbria |

| Marche |

| Latium |

| South |

| Abruzzo |

| Molise |

| Campania |

| Apulia |

| Basilicata |

| Calabria |

| Islands |

| Sicily |

| Sardinia |

| Region/AP | Law/Programme | Level of Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Piedmont | LR 17/2019 | Low |

| Liguria | LR 48/2009 | Low |

| Veneto | LR 23/2017 | High |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | LR 22/2014 | High |

| Emilia-Romagna | DGR 2299/2004 | High |

| Umbria | LR 11/2015 | High |

| Marche | LR 1/2019 | Low |

| Abruzzo | LR 16/2016 | Low |

| Campania | LR 2/2018 | Low |

| Basilicata | LR 29/2017 | Low |

| Calabria | LR 12/2018 | Low |

| Apulia | LR 16/2019 | Low |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barbabella, F.; Cela, E.; Socci, M.; Lucantoni, D.; Zannella, M.; Principi, A. Active Ageing in Italy: A Systematic Review of National and Regional Policies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010600

Barbabella F, Cela E, Socci M, Lucantoni D, Zannella M, Principi A. Active Ageing in Italy: A Systematic Review of National and Regional Policies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010600

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbabella, Francesco, Eralba Cela, Marco Socci, Davide Lucantoni, Marina Zannella, and Andrea Principi. 2022. "Active Ageing in Italy: A Systematic Review of National and Regional Policies" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010600

APA StyleBarbabella, F., Cela, E., Socci, M., Lucantoni, D., Zannella, M., & Principi, A. (2022). Active Ageing in Italy: A Systematic Review of National and Regional Policies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010600