Does Exposure to High Job Demands, Low Decision Authority, or Workplace Violence Mediate the Association between Employment in the Health and Social Care Industry and Register-Based Sickness Absence? A Longitudinal Study of a Swedish Cohort

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Sickness Absence in the Health and Social Care Industry

1.2. Job Demands and Decision Authority in the Health and Social Care Industry

1.3. Workplace Violence in the Health and Social Care Industry

1.4. Variation in Sickness Absence and Psychosocial Work Factors on Industry Level

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Sample

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Outcome Variable

Sickness Absence

2.3.2. Predictor Variable

2.3.3. Mediating Variables

2.3.4. Covariates

2.4. Analytical Strategy

2.4.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.4.2. Autoregressive Cross-Lagged Mediation Models within a Multilevel Structural Equation Modelling (MSEM) Framework

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. The Association between Employment in the Health and Social Care Industry and Sickness Absence (Model 1)

3.3. The Mediating Role of High Job Demands (Model 2)

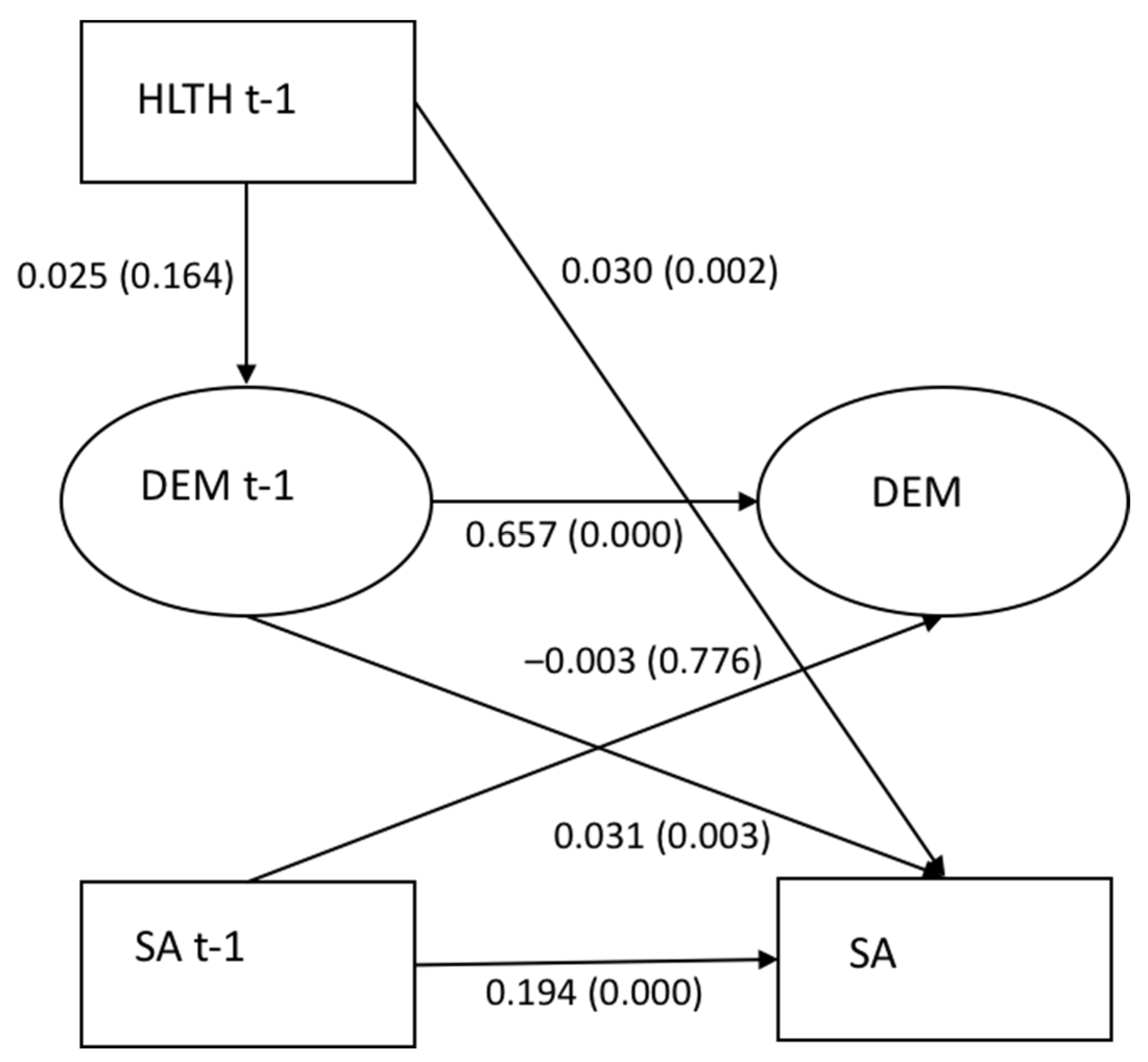

3.4. The Mediating Role of Low Decision Authority (Model 3)

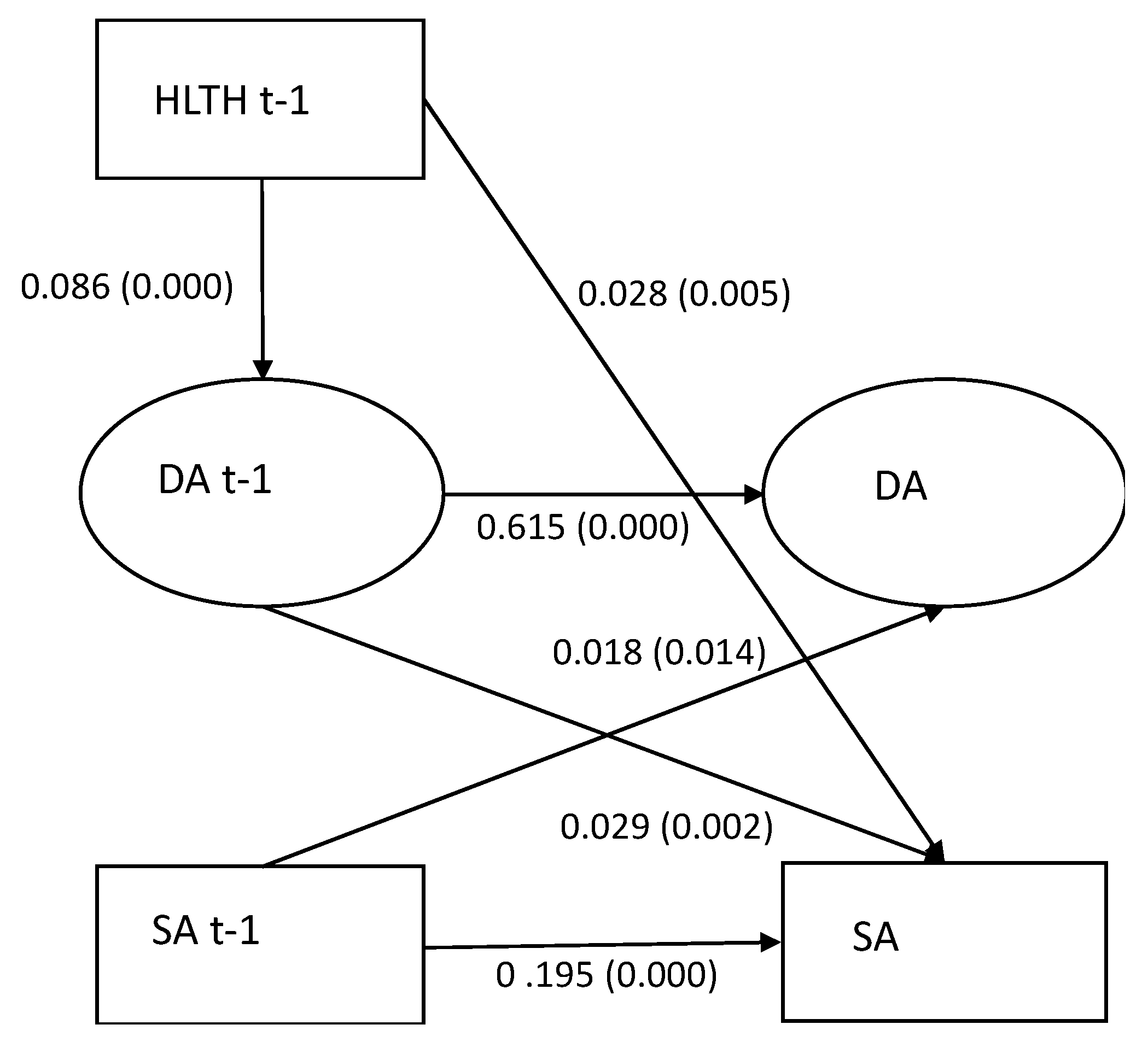

3.5. The Mediating Role of Exposure to Workplace Violence (Model 4)

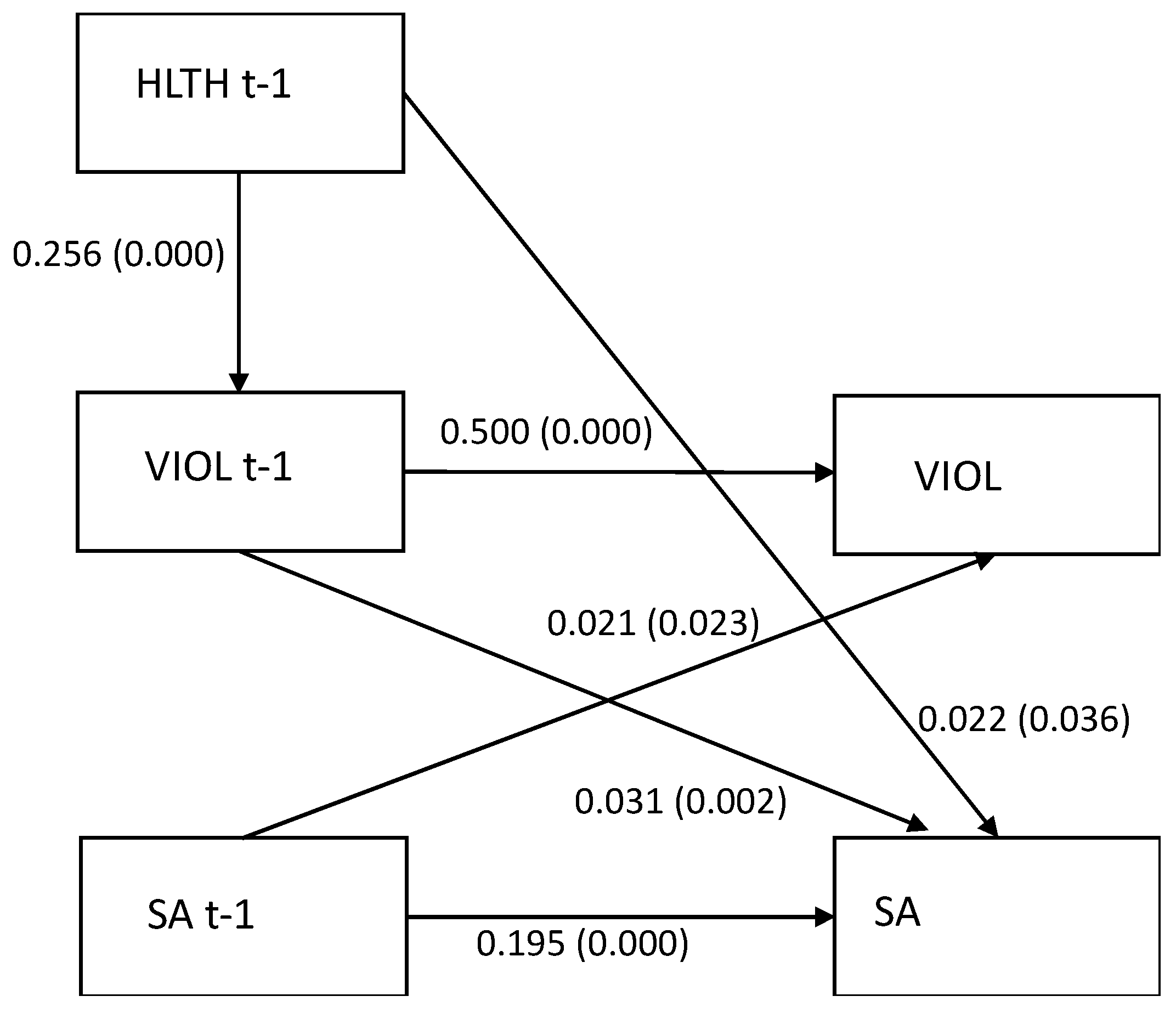

4. Discussion

4.1. The Association between Employment in the Health and Social Care Industry and Sickness Absence

4.2. The Mediating Role of High Job Demands

4.3. The Mediating Role of Low Decision Authority

4.4. The Mediating Role of Exposure to Workplace Violence

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Swedish Social Insurance Agency. Sick Leave at the Swedish Labour Market. Sick Leave Longer than 14 Days and Termination of Sick Leave within 180 Days by Industry and Occupation; Swedish Social Insurance Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, S.L.; Coon, J.T.; Fleming, L.E.; Carroll, L.; Bethel, A.; Wyatt, K. Whole-system approaches to improving the health and wellbeing of healthcare workers: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krane, L.; Johnsen, R.; Fleten, N.; Nielsen, C.V.; Stapelfeldt, C.M.; Jensen, C.; Braaten, T. Sickness absence patterns and trends in the health care sector: 5-year monitoring of female municipal employees in the health and care sectors in Norway and Denmark. Hum. Resour. Health 2014, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aagestad, C.; Tyssen, R.; Sterud, T. Do work-related factors contribute to differences in doctor-certified sick leave? A prospective study comparing women in health and social occupations with women in the general working population. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 235. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Social Insurance Agency. Social Insurance Report 2014:4. Sick Leave Due to Mental Disorders. A Study of the Swedish Population Aged 16–64; Swedish Social Insurance Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek, R.; Theorell, T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity and the Reconstruction of Working Life; Basic Books Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cerdas, S.; Härenstam, A.; Johansson, G.; Nyberg, A. Development of job demands, decision authority and social support in industries with different gender composition—Sweden, 1991–2013. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nyberg, A.; Härenstam, A.; Peristera, P.; Johansson, G. Organizational and social working conditions for women and men in industries with different types of production and gender composition. A comparative study of the development in Sweden between 1991 and 2017. In Gendered Norms at Work: New Perspectives on Work Environment and Health; Keisu, B.-I., Brodin, H., Tafvelin, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, S.B.; Modini, M.; Joyce, S.; Milligan-Saville, J.S.; Tan, L.; Mykletun, A.; Bryant, R.A.; Christensen, H.; Mitchell, P.B. Can work make you mentally ill? A systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 74, 301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, A.; Scovelle, A.J.; King, T.L.; Madsen, I. Exposure to work stress and use of psychotropic medications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2019, 73, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoman, Y.; el May, E.; Marca, S.C.; Wild, P.; Bianchi, R.; Bugge, M.D.; Caglayan, C.; Cheptea, D.; Gnesi, M.; Godderis, L.; et al. Predictors of Occupational Burnout: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theorell, T.; Hammarström, A.; Aronsson, G.; Bendz, L.T.; Grape, T.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Hall, C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aronsson, G.; Theorell, T.; Grape, T.; Hammarström, A.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Träskman-Bendz, L.; Hall, C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swedish Social Insurance Agency. Social Insurance Report 2020:8. Mental Disorder Sick Leave—A Register Study of the Swedish Working Population in Ages 20 to 69 Years; Swedish Social Insurance Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Duijts, S.F.; Kant, I.; Swaen, G.M.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Zeegers, M.P. A meta-analysis of observational studies identifies predictors of sickness absence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.L.; Rugulies, R.; Christensen, K.B.; Smith-Hansen, L.; Kristensen, T.S. Psychosocial work environment predictors of short and long spells of registered sickness absence during a 2-year follow up. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2006, 48, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stromholm, T.; Pape, K.; Ose, S.O.; Krokstad, S.; Bjorngaard, J.H. Psychosocial working conditions and sickness absence in a general population: A cohort study of 21,834 workers in Norway (The HUNT Study). J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015, 57, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens, H.; Clays, E.; de Clercq, B.; Casini, A.; de Bacquer, D.; Kittel, F.; Braeckman, L. The relation between psychosocial risk factors and cause-specific long-term sickness absence. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 24, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duchaine, C.S.; Aubé, K.; Gilbert-Ouimet, M.; Vézina, M.; Ndjaboué, R.; Massamba, V.; Talbot, D.; Lavigne-Robichaud, M.; Trudel, X.; Pena-Gralle, A.P.B.; et al. Psychosocial Stressors at Work and the Risk of Sickness Absence Due to a Diagnosed Mental Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slany, C.; Schütte, S.; Chastang, J.-F.; Parent-Thirion, A.; Vermeylen, G.; Niedhammer, I. Psychosocial work factors and long sickness absence in Europe. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2013, 20, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Clausen, T.; Nielsen, K.; Carneiro, I.G.; Borg, V. Job demands, job resources and long-term sickness absence in the Danish eldercare services: A prospective analysis of register-based outcomes. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roelen, C.; van Rhenen, W.; Schaufeli, W.; van der Klink, J.; Magerøy, N.; Moen, B.; Bjorvatn, B.; Pallesen, S. Mental and physical health-related functioning mediates between psychological job demands and sickness absence among nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 1780–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leineweber, C.; Marklund, S.; Gustafsson, K.; Helgesson, M. Work environment risk factors for the duration of all cause and diagnose-specific sickness absence among healthcare workers in Sweden: A prospective study. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 77, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Labour Conference. Convention 190. In Proceedings of the Convention Concerning the Elimination of Violence and Harassment in the World of Work, Geneva, Switzerland, 10 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg, A.; Rajaleid, K.; Kecklund, G.; Magnusson Hanson, L. Våld i Arbetslivet inom Hälso- och Sjukvård, Socialt Arbete och Utbildningssektorn. Kunskapsläge och Fortsatt Forskningsbehov [Work-Place Violence in Health and Social Care and Education. State of the Evidence and Research Gaps]. Available online: https://forte.se/app/uploads/2020/06/fort-0013-rapport-vald-i-arbetslivet-ta.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Lanctot, N.; Guay, S. The aftermath of workplace violence among healthcare workers: A systematic review of the consequences. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2014, 19, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aagestad, C.; Tyssen, R.; Johannessen, H.A.; Gravseth, H.M.; Tynes, T.; Sterud, T. Psychosocial and organizational risk factors for doctor-certified sick leave: A prospective study of female health and social workers in Norway. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hogh, A.; Clausen, T.; Borg, V. Acts of offensive behaviour and risk of long-term sickness absence in the Danish elder-care services: A prospective analysis of register-based outcomes. PsycEXTRA Dataset 2012, 85, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugulies, R.; Christensen, K.B.; Borritz, M.; Villadsen, E.; Bültmann, U.; Kristensen, T.S. The contribution of the psychosocial work environment to sickness absence in human service workers: Results of a 3-year follow-up study. Work. Stress 2007, 21, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nyberg, A.; Kecklund, G.; Hanson, L.M.; Rajaleid, K. Workplace violence and health in human service industries: A systematic review of prospective and longitudinal studies. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 78, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronsson, V.; Toivanen, S.; Leineweber, C.; Nyberg, A. Can a poor psychosocial work environment and insufficient organizational resources explain the higher risk of ill-health and sickness absence in human service occupations? Evidence from a Swedish national cohort. Scand. J. Public Health 2019, 47, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohar, B.; Larivière, M.; Lightfoot, N.; Wenghofer, E.; Nowrouzi-Kia, B. Meta-analysis of nursing-related organizational and psychosocial predictors of sickness absence. Occup. Med. 2020, 70, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson Hanson, L.L.; Leineweber, C.; Persson, V.; Hyde, M.; Theorell, T.; Westerlund, H. Cohort Profile: The Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health (SLOSH). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 691–692i. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanne, B.; Torp, S.; Mykletun, A.; Dahl, A.A. The Swedish Demand—Control—Support Questionnaire (DCSQ): Factor structure, item analyses, and internal consistency in a large population. Scand. J. Public Health 2005, 33, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransson, E.I.; Nyberg, S.T.; Heikkilä, K.; Alfredsson, L.; Bacquer, D.D.; Batty, G.D.; Bonenfant, S.; Casini, A.; Clays, E.; Goldberg, M.; et al. Comparison of alternative versions of the job demand-control scales in 17 European cohort studies: The IPD-Work consortium. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cole, D.A.; Maxwell, S.E. Testing Mediational Models with Longitudinal Data: Questions and Tips in the Use of Structural Equation Modeling. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Selig, J.; Preacher, K.J. Mediation Models for Longitudinal Data in Developmental Research. Res. Hum. Dev. 2009, 6, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J. Advances in Mediation Analysis: A Survey and Synthesis of New Developments. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 825–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Zhang, Z.; Zyphur, M.J. Alternative methods for assessing mediation in multilevel data: The advantages of multilevel SEM. Struct. Equ. Modeling 2011, 18, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Zyphur, M.J.; Zhang, Z. A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychol. Methods 2010, 15, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lockhart, G.; MacKinnon, D.P.; Ohlrich, V. Mediation Analysis in Psychosomatic Medicine Research. Psychosom. Med. 2011, 73, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Little, T.D. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pompeii, L.; Dement, J.; Schoenfisch, A.; Lavery, A.; Souder, M.; Smith, C.; Lipscomb, H. Perpetrator, worker and workplace characteristics associated with patient and visitor perpetrated violence (Type II) on hospital workers: A review of the literature and existing occupational injury data. J. Saf. Res. 2013, 44, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hox, J.J. Quantitative Methodology Series. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications, 2nd ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, B.O. Multilevel Covariance Structure Analysis. Sociol. Methods Res. 1994, 22, 376–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Women | Men | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/means | %/st.dev | n/means | %/st.dev | n/means | %/st.dev | |

| Predictor | ||||||

| Employment in Health and Social Care | ||||||

| Yes | 675 | 32.05 | 105 | 5.80 | 780 | 19.92 |

| No | 1431 | 67.95 | 1705 | 94.20 | 3136 | 80.08 |

| Putative mediators | ||||||

| Job Demands | 2.59 | 0.56 | 2.58 | 0.53 | 2.59 | 0.55 |

| Decision Authority | 1.72 | 0.48 | 1.68 | 0.49 | 1.70 | 0.49 |

| Workplace Violence | ||||||

| No | 1626 | 77.06 | 1601 | 88.36 | 3227 | 82.28 |

| Yes | 484 | 22.94 | 211 | 11.64 | 695 | 17.75 |

| Outcome variable | ||||||

| Sickness Absence | ||||||

| 0 days | 1801 | 84.79 | 1669 | 91.45 | 3470 | 87.87 |

| >0 days | 323 | 15.21 | 156 | 8.55 | 479 | 12.13 |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Women | - | - | - | - | 2126 | 53.78 |

| Men | - | - | - | - | 1826 | 46.22 |

| Age | ||||||

| 1 < 34 years | 249 | 11.94 | 225 | 12.53 | 474 | 12.21 |

| 2 35–44 years | 522 | 25.04 | 470 | 26.17 | 992 | 25.56 |

| 3 45–54 years | 729 | 34.96 | 542 | 30.18 | 1271 | 32.75 |

| 4 55–64 years | 580 | 27.82 | 537 | 29.90 | 1117 | 28.78 |

| 5 > 64 years | 5 | 0.24 | 22 | 1.22 | 27 | 0.70 |

| Education | ||||||

| 1 ≤ 9 years | 303 | 14.35 | 324 | 17.94 | 627 | 16 |

| 2 ≤ 12 years | 431 | 20.45 | 454 | 25.14 | 885 | 22.59 |

| 3 University < 3 years | 368 | 17.42 | 407 | 22.54 | 775 | 19.78 |

| 4 University ≥ 3years | 376 | 17.80 | 197 | 10.91 | 573 | 14.62 |

| 5 Research Education | 634 | 30.02 | 424 | 23.48 | 1058 | 27 |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| 0 Not Married/cohabited | 932 | 43.86 | 812 | 44.47 | 1744 | 44.14 |

| 1 married/cohabited | 1193 | 53.14 | 1014 | 55.53 | 2207 | 55.86 |

| Children living at home | ||||||

| 0 No | 1021 | 48.48 | 851 | 47.49 | 1872 | 48.02 |

| 1 Yes | 1085 | 51.52 | 941 | 52.51 | 2026 | 51.98 |

| B (SE) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Health and social care (HLTH)—Sickness Absence (SA) model | ||

| Sickness Absence (SA) t | ||

| Sickness Absence (SA) t-1 | 0.195 (0.013) | 0.000 |

| Health and social care (HLTH) t-1 | 0.032 (0.010) | 0.002 |

| Age | −0.033 (0.010) | 0.001 |

| Children living at home | −0.017 (0.010) | 0.109 |

| Married/co-habitant | −0.022 (0.009) | 0.015 |

| Education | −0.050 (0.009) | 0.000 |

| Gender | 0.069 (0.008) | 0.000 |

| Health and social care (HLTH) t | ||

| Health and social care (HLTH) t-1 | 0.918 (0.006) | 0.000 |

| Sickness Absence (SA) t-1 | 0.005 (0.004) | 0.225 |

| Age | 0.003 (0.004) | 0.514 |

| Children living at home | −0.003 (0.003) | 0.362 |

| Married/co-habitant | −0.002 (0.003) | 0.407 |

| Education | 0.000 (0.003) | 0.935 |

| Gender | 0.025 (0.003) | 0.000 |

| 2. Health and social care (HLTH)—High demands (DEM)—Sickness Absence (SA) model | ||

| Demands (DEM) t-1 | ||

| Health and social care (HLTH) t-1 | 0.025 (0.018) | 0.164 |

| Age | −0.060 (0.018) | 0.001 |

| Children living at home | 0.015 (0.016) | 0.360 |

| Married/co-habitant | 0.002 (0.016) | 1.351 |

| Education | 0.137 (0.018) | 0.000 |

| Gender | 0.068 (0.017) | 0.000 |

| Demands (DEM) t | ||

| Sickness Absence (SA) t-1 | −0.003 (0.009) | 0.776 |

| Demands (DA) t-1 | 0.657 (0.024) | 0.000 |

| Age | −0.060 (0.018) | 0.001 |

| Children living at home | 0.015 (0.016) | 0.360 |

| Married/co-habitant | 0.022 (0.016) | 0.177 |

| Education | 0.137 (0.018) | 7.728 |

| Gender | 0.068 (0.017) | 3.899 |

| Sickness absence (SA) t | ||

| Sickness absence (SA) t-1 | 0.194 (0.013) | 0.000 |

| Health and social care (HLTH) t-1 | 0.030 (0.010) | 0.002 |

| Demands (DEM) t-1 | 0.031 (0.010) | 0.003 |

| Age | −0.032 (0.010) | 0.001 |

| Children living at home | −0.017 (0.010) | 0.099 |

| Married/co-habitant | −0.023 (0.009) | 0.012 |

| Education | −0.054 (0.009) | 0.000 |

| Gender | 0.067 (0.008) | 0.000 |

| 3. Health and social care (HLTH)—Low decision authority (DA)—Sickness absence (SA) model | ||

| Decision Authority (DA) t-1 | ||

| Health and social care (HLTH) t-1 | 0.086 (0.014) | 0.000 |

| Age | −0.122 (0.014) | 0.000 |

| Children living at home | −0.021 (0.014) | 0.135 |

| Married/co-habitant | −0.041 (0.014) | 0.002 |

| Educ | −0.173 (0.013) | 0.000 |

| Sex | 0.084 (0.015) | 0.000 |

| Decision Authority (DA) t | ||

| Decision Authority (DA) t-1 | 0.615 (0.009) | 0.000 |

| Sickness absence (SA) t-1 | 0.018 (0.007) | 0.014 |

| Age | −0.030 (0.008) | 0.000 |

| Children living at home | −0.001 (0.007) | 0.924 |

| Married/co-habitant | −0.008 (0.007) | 0.231 |

| Education | −0.066 (0.007) | 0.000 |

| Gender | 0.048 (0.007) | 0.000 |

| Sickness absence (SA) t | ||

| Sickness absence (SA) t-1 | 0.195 (0.013) | 0.000 |

| Health and social care (HLTH) t-1 | 0.028 (0.010) | 0.005 |

| Decision Authority (DA) t-1 | 0.029 (0.009) | 0.002 |

| Age | −0.030 (0.010) | 0.005 |

| Children living at home | −0.016 (0.010) | 0.121 |

| Married/co-habitant | −0.021 (0.009) | 0.022 |

| Education | −0.045 (0.009) | 0.000 |

| Gender | 0.067 (0.008) | 0.000 |

| 4. Health and social care (HLTH)—Workplace violence (VIOL)—Sickness absence (SA) model | ||

| Workplace violence (VIOL) t-1 | ||

| Health and social care (HLTH) t-1 | 0.256 (0.016) | 0.000 |

| Age | −0.112 (0.014) | 0.000 |

| Children living at home | −0.001 (0.014) | 0.937 |

| Married/co-habitant | −0.022 (0.012) | 0.081 |

| Education | −0.011 (0.012) | 0.386 |

| Gender | 0.039 (0.012) | 0.001 |

| Workplace violence (VIOL) t | ||

| Workplace violence (VIOL) t-1 | 0.500 (0.015) | 0.000 |

| Sickness absence (SA) t-1 | 0.021 (0.009) | 0.023 |

| Age | −0.030 (0.010) | 0.002 |

| Children living at home | −0.017 (0.010) | 0.107 |

| Married/co-habitant | −0.021 (0.009) | 0.018 |

| Education | −0.050 (0.009) | 0.000 |

| Gender | 0.068 (0.008) | 0.000 |

| Sickness absence (SA) t | ||

| Sickness absence (SA) t-1 | 0.195 (0.013) | 0.000 |

| Health and social care (HLTH) t-1 | 0.022 (0.010) | 0.036 |

| Workplace violence (VIOL) t-1 | 0.031 (0.010) | 0.002 |

| Age | −0.030(0.010) | 0.036 |

| Children living at home | −0.017(0.010) | 0.107 |

| Married/co-habitant | −0.021(0.009) | 0.018 |

| Education | −0.050(0.009) | 0.000 |

| Gender | 0.068(0.008) | 0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nyberg, A.; Peristera, P.; Toivanen, S.; Johansson, G. Does Exposure to High Job Demands, Low Decision Authority, or Workplace Violence Mediate the Association between Employment in the Health and Social Care Industry and Register-Based Sickness Absence? A Longitudinal Study of a Swedish Cohort. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010053

Nyberg A, Peristera P, Toivanen S, Johansson G. Does Exposure to High Job Demands, Low Decision Authority, or Workplace Violence Mediate the Association between Employment in the Health and Social Care Industry and Register-Based Sickness Absence? A Longitudinal Study of a Swedish Cohort. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleNyberg, Anna, Paraskevi Peristera, Susanna Toivanen, and Gun Johansson. 2022. "Does Exposure to High Job Demands, Low Decision Authority, or Workplace Violence Mediate the Association between Employment in the Health and Social Care Industry and Register-Based Sickness Absence? A Longitudinal Study of a Swedish Cohort" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010053

APA StyleNyberg, A., Peristera, P., Toivanen, S., & Johansson, G. (2022). Does Exposure to High Job Demands, Low Decision Authority, or Workplace Violence Mediate the Association between Employment in the Health and Social Care Industry and Register-Based Sickness Absence? A Longitudinal Study of a Swedish Cohort. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010053