Psychomedical Interventions with Transgender People in Portugal and Brazil: A Critical Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis Assumptions: Constructionist and Feminist Thematic Analysis

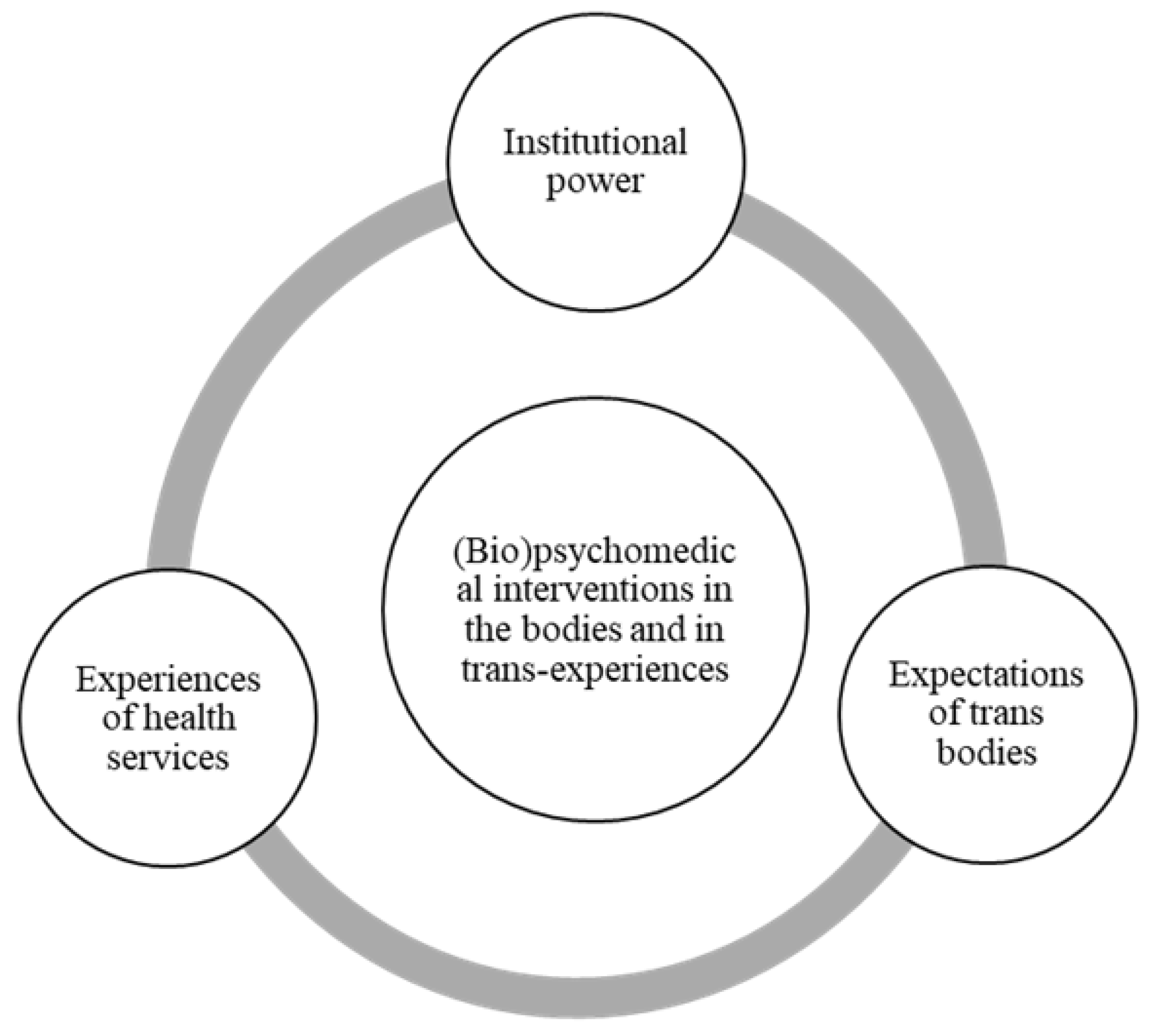

3. Results and Discussion

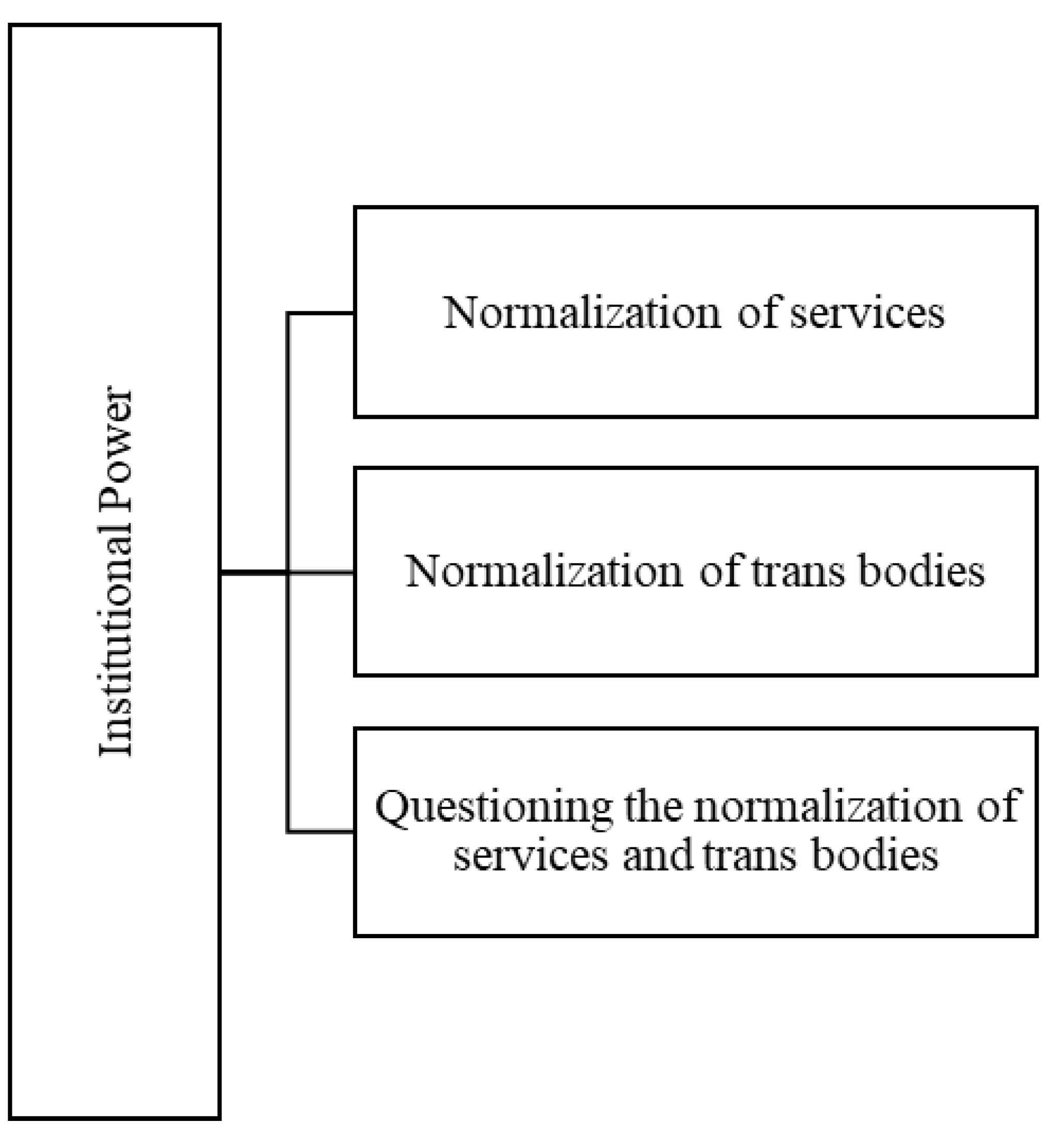

3.1. Institutional Power

“She goes to the center, requests care from the social worker, imagine that she talks to the social worker, look, I’m a transsexual, this and that, the social worker will forward it to the psychologist, she has to go through the psychologist and there will be all that chatter (…), they will indicate her to an endocrine, and it is a process that takes a long time. And then until it culminates in the surgery, in the surgery row, actually, not in the surgery, the surgery row”.(3-F.F.BR.SE)

“I’m aware that it’s based on standardizing assumptions, ok, so if it’s T. now and it’s been recognized that it’s T., we want it to be T. all the way, and from there they could base their support for me to do the surgeries. (…) although in my daily life I can base trans issues on other assumptions, and I am claiming that I understand that my parents have these assumptions and accept me according to these assumptions. But they are complete, they support me 100% and they make a point of giving their love 100%. And they are ok with all this. And very proud of me”.(3-T.F.PT.PL)

“(…) I know that each one has a desire, but I think it was a desire that was installed (…). I think it doesn’t exist unless the other has made it the norm (…). “All [trans woman] cannot touch your penis, all cannot, all had conflict, all from little ones”, (…) evidently there is a certain femininity, but not a rejection of the penis, even because it is an object of pleasure, in all the senses, and there are traumas that lead you to… it is not a child who has all the expertise of assembling these speeches, then one starts to really see things”.(1-PFBR.S)

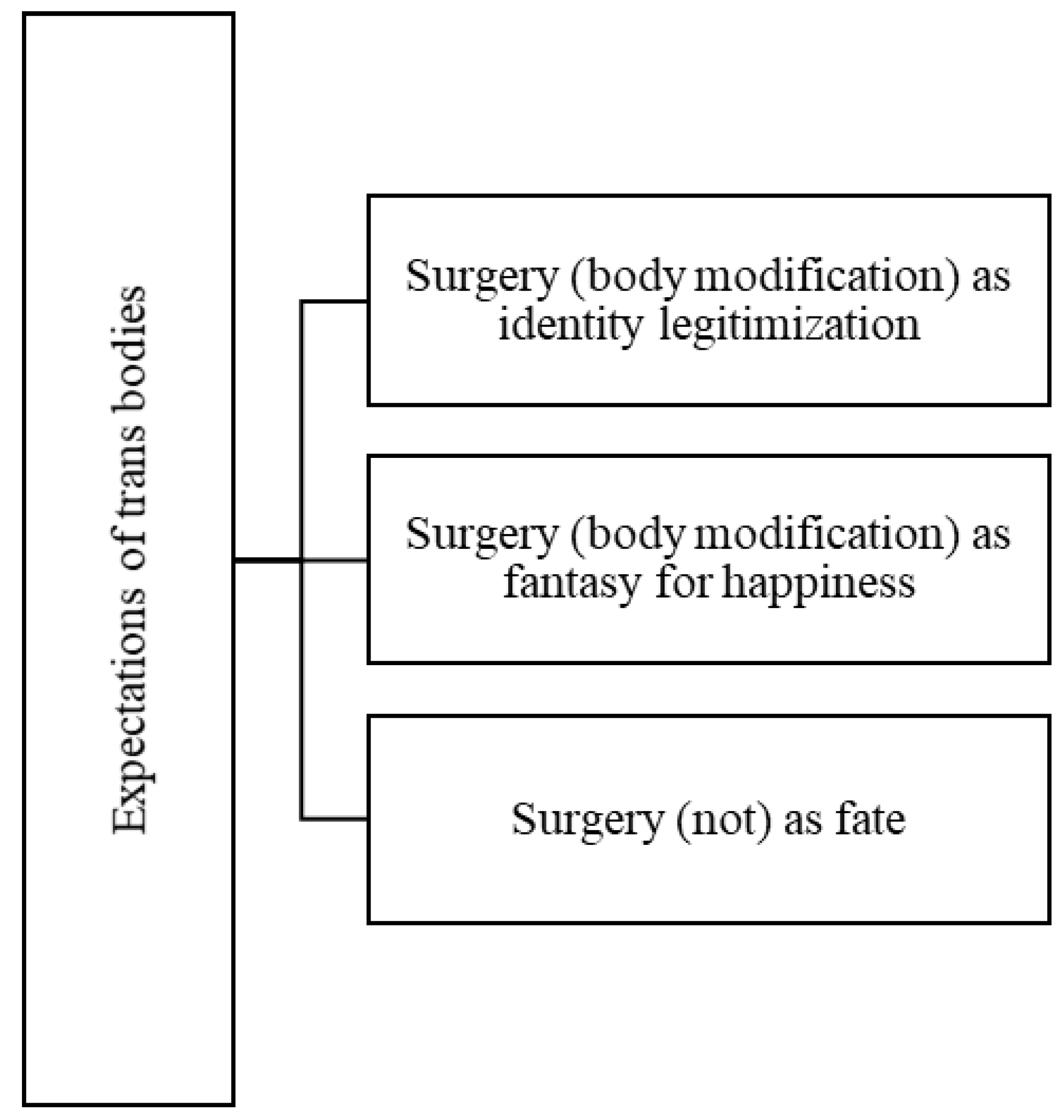

3.2. Expectations of Trans Bodies

“(…) so I end up going back to what I said that I was deprived of a basic right simply because I don’t have the surgery. (…) no one is seeing my genitalia, but my face, my construction as a person, everyone is seeing it. And my construction as a person does not match that name, often with that identity photo, but people prefer to see what is covered than what is in their face”.(23-L.F.BR.S)

“You have to have surgery so that you feel complete and this completeness is pure fantasy that she will never have, neither with this surgery nor with any other surgery in the world or only if you were to take her brain out and she would live without memory”.(1-P.F.BR.S)

“If I had very good, quality surgery, I would do it. I always felt like having a penis, but I don’t want to have a defective penis. I don’t want to have a defective penis and I also have no problem with my genitalia. (…) I would just like to have a penis that works and that is pleasant for me and also for other people that I relate to. I never wanted something strange, let’s say, nothing that would mutilate me. You know, I don’t have the courage to do that”.(20-C.M.BR.S)

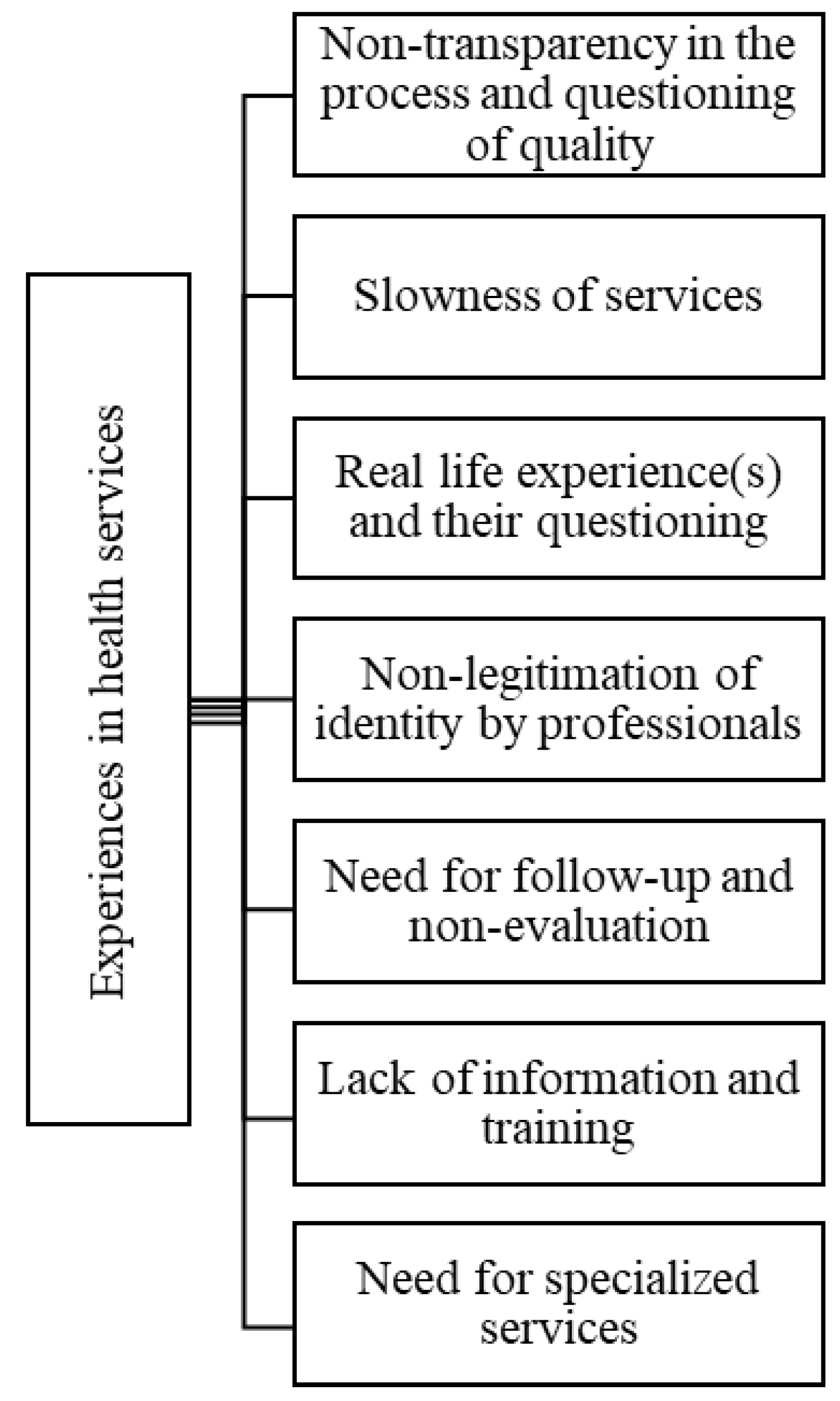

3.3. Experiences in Health Services

“(…) now in Coimbra, we don’t know. I know how few surgeries they are doing. I even did my augmentation mammoplasty there and everything went well, and I am satisfied with the result. I feel this validates the health service. However, doing my genital surgery there, I didn’t feel the slightest confidence in the service and didn’t want to risk it”.(3-T.F.PT.PL)

“(…) with a very long line, with abuses, medical arbitrariness, with very, let’s say, aesthetically negative surgical results, you can already find a series of complaints. (…) But one of the biggest complaints is really the waiting line. (…) It’s not for nothing that people go by other means, they won’t wait, it’s their life. Nobody wants to wait to be happy”.(21-L.M.BR.S)

“Sometimes people, and especially transsexual women who have not yet done any hormone therapy and cannot at all have a female aspect, are not physically prepared for this experience but are somehow forced to have it not as an experience but rather as a test and that is a situation that is packed with dangers and even from being physically on the street”.(6-R.F.PT.GL)

“But I’m interested in making the registration change and everything else, only we lose the will. It’s so many documents you have to take along and all the medical reports, you know. My word is not enough, you have to be the doctor, then…”.(18-B.F.BR.S)

“I think medical follow-up is of fundamental importance but not in the way it is approached today. In a pathological way, as if it were an illness, I don’t see it that way, but medical accompaniment is important, psychiatry, psychology, in short, are there to help us but not in this way of treating the person as sick”.(18-B.F.BR.S.)

“(…) doesn’t have a focus on trans health, much less on male trans, it doesn’t. So the trans man is still obliged to go and take care of himself in a gynaecologist. And suddenly a trans man arrives in front of her and she doesn’t know how to do it properly. But it’s the only option he has and even though he has a biologically feminine body that needs treatments directed to this area, he doesn’t have a professional prepared to deal with that, with this novelty, that there is a trans man with a feminine body, and from there, all kinds of moral, ethical, physical constraints happen to this man (…)”.(17-B.M.BR.CO)

“At the level of specific care in Portugal, we have much to do and develop. (…) there is a process of adaptation that is not taking place and that also has to be done, both for health professionals to be prepared to receive trans people, and for trans persons themselves as the health care is not the same. A trans person cannot access general health care in the same way as a cis woman. There are specificities that have to be respected and trans persons also require educating in”.(3-T.F.PT.PL)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Panteras, R. A Vergonha que se Esperava. 2006. Available online: http://www.panterasrosa.blogspot.pt/2006_07_01_archive.html (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Gómez, G.E.; de Antonio, I. Ser Transexual. Dirigido al Paciente, a su Familia, y al Entorno Sanitario, Judicial y Social; Editorial Glosa: Barcelona, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Money, J. Sex Reassignment as Related to Hermaprhoditism and Transsexualism. In Transsexualism and Sex reassignment; Green, R., Money, J., Eds.; The Johns Hopkins Press: Maryland, MD, USA, 1969; pp. 91–114. [Google Scholar]

- Coimbra, C. Guardiães da Ordem. Uma Viagem Pelas Práticas psi do Brasil do Milagre; Oficina do Autor: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Missé, M. Transexualidades: Outras Miradas Posibles, 2nd ed.; Egales Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Platero, R.L. Transexualidades: Acompañamiento, Factores de Salud y Recursos Educativos; Edicions Bellaterra: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, L. Viagens Trans(Género) em Portugal e no Brasil: Uma Aproximação Psicológica Feminista Crítica. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Preciado, P.B. Manifesto Contra-Sexual; Orfeu Negro: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, L.; Carneiro, N.S.; Nogueira, C. A history of scientific, medical and psychological approaches to transsexualities and their critical approach. Saúde E Soc. 2021, 30, e200768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilário, A.P. Rethinking trans identities within the medical and psychological community: A path towards the depathologization and self-definition of gender identification in Portugal? J. Gend. Stud. 2018, 29, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. ICD-11: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 2019. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Coll-Planas, G.; Missé, M. Me Gustaría ser Militar. Reproducción de la Masculinidad Hegemónica en la Patologización de la Transexualidad. Prism. Soc. 2014, 13, 407–432. [Google Scholar]

- Schwend, A.S. Trans health care from a depathologization and human rights perspective. Public Health Rev. 2020, 41, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garaizabal, C. Transexualidades, Identidades e Feminismos. In El Género Desordenado: Críticas en Torno a la Patologización de la Transexualidad; Missé, M., Coll-Planas, G., Eds.; Egales: Barcelona, Spain, 2010; pp. 125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.L. Os Homens Transexuais Brasileiros e o Discurso Pela (des)Patologização da Transexualidade. In Transfeminismo: Teorias e Práticas; Jesus, J.G., Ed.; Metanoia Editora: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2014; pp. 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Platero, R.L.; Rosón, M. De la parada de los monstruos a los monstruos de lo cotidiano: La diversidade funcional y sexualidad no normativa. Feminismos 2012, 19, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stryker, S. Prefacio. In Transrespeto versus Transfobia en el Mundo: Un Studio Comparativo de la Situación de los Derechos Humanos de las Personas Trans; Serie de Publicaciones de TVT Transgender Europe; Balzer, C., Hutta, J.S., Eds.; TGEU: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. Desdiagnosticando o Gênero. Physis Rev. Saúde Coletiva 2009, 19, 95–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soares, M.; Moreira, C.; Rodrigues, L.; Nogueira, C. (Des)construção de masculinidades de homens trans, entre Portugal e Brasil. Ex Aequo 2021, 43, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, L. Em defesa da dignidade: Moralidades e emoções nas demandas por direitos de pessoas transexuais. Mana 2020, 26, e262205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fraser, L. Depth psychotherapy with transgender people. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2009, 24, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, A. The ten tasks of the mental health provider: Recommendations for revision of the World Professional Association for transgender health’s standards of care. Int. J. Transgend. 2009, 11, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwickl, S.; Wong, A.; Bretherton, I.; Rainier, M.; Chetcuti, D.; Zajac, J.D.; Cheung, A.S. Health needs of trans and gender diverse adults in Australia: A qualitative analysis of a national community survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goffman, E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity; Peng: London, UK, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. Quadros de Guerra: Quando a Vida é Passível de Luto? Civilização Brasileira: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, J.M.; Costa, C.G.; Carneiro, N.S. Problematizando a Humanidade: Para uma Psicologia Crítica Feminista Queer. Annual Review of Critical Psychology. 2014. Available online: http://www.discourseunit.com/arcp11/4-problematizando.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Dezanove. Ministro da Saúde Questionado Sobre a Falta das Cirurgias de Reatribuição de Sexo. 2015. Available online: http://dezanove.pt/ministro-da-saude-questionado-sobre-a-767941 (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Fernández-Fígares, K. Historia de la Patologización y Despatologización de las Variantes de Género. In El Género Desordenado: Críticas en Torno a la Patologización de la Transexualidad; Missé, M., Coll-Planas, G., Eds.; Egales: Barcelona, Spain, 2010; pp. 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, I. Transexualidade: Vivência do Processo de Transição no Contexto dos Serviços de Saúde. Acta Med. Port. 2010, 23, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Butler, J. Transexualidad, Transformaciones. In El Género Desordenado: Críticas en Torno a la Patologización de la Transexualidad; Missé, M., Coll-Planas, G., Eds.; Egales: Barcelona, Spain, 2010; pp. 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Arán, M.; Murta, D. Do diagnóstico de transtorno de identidade de género às redescrições da experiência da transexualidade: Uma reflexão sobre género, tecnologia e saúde. Physis Rev. Saúde Coletiva 2009, 19, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, M.; Schramm, F. Limites e possibilidades do exercício da autonomia nas práticas terapêuticas de modificação corporal e alteração da identidade sexual. Physis Rev. Saúde Coletiva 2008, 19, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitelli, R.; Scandurra, C.; Pacifico, R.; Selvino, M.S.; Picariello, S.; Amodeo, A.L.; Valerio, P.; Giami, A. Trans identities and medical practice in Italy: Self-positioning towards gender affirmation surgery. Sexologies 2017, 26, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, F.; Barboza, H.; Guimarães, A. A moralidade da transexualidade: Aspectos bioéticos e jurídicos. Rev. Redbioética 2011, 1, 66–77. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, L.; Soares, M.; Nogueira, C. Psychomedical Interventions with Transgender People in Portugal and Brazil: A Critical Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010267

Rodrigues L, Soares M, Nogueira C. Psychomedical Interventions with Transgender People in Portugal and Brazil: A Critical Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010267

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues, Liliana, Matilde Soares, and Conceição Nogueira. 2022. "Psychomedical Interventions with Transgender People in Portugal and Brazil: A Critical Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010267

APA StyleRodrigues, L., Soares, M., & Nogueira, C. (2022). Psychomedical Interventions with Transgender People in Portugal and Brazil: A Critical Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010267