Workplace Incivility and Turnover Intention in Organizations: A Meta-Analytic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Workplace Incivility

1.2. Turnover Intention

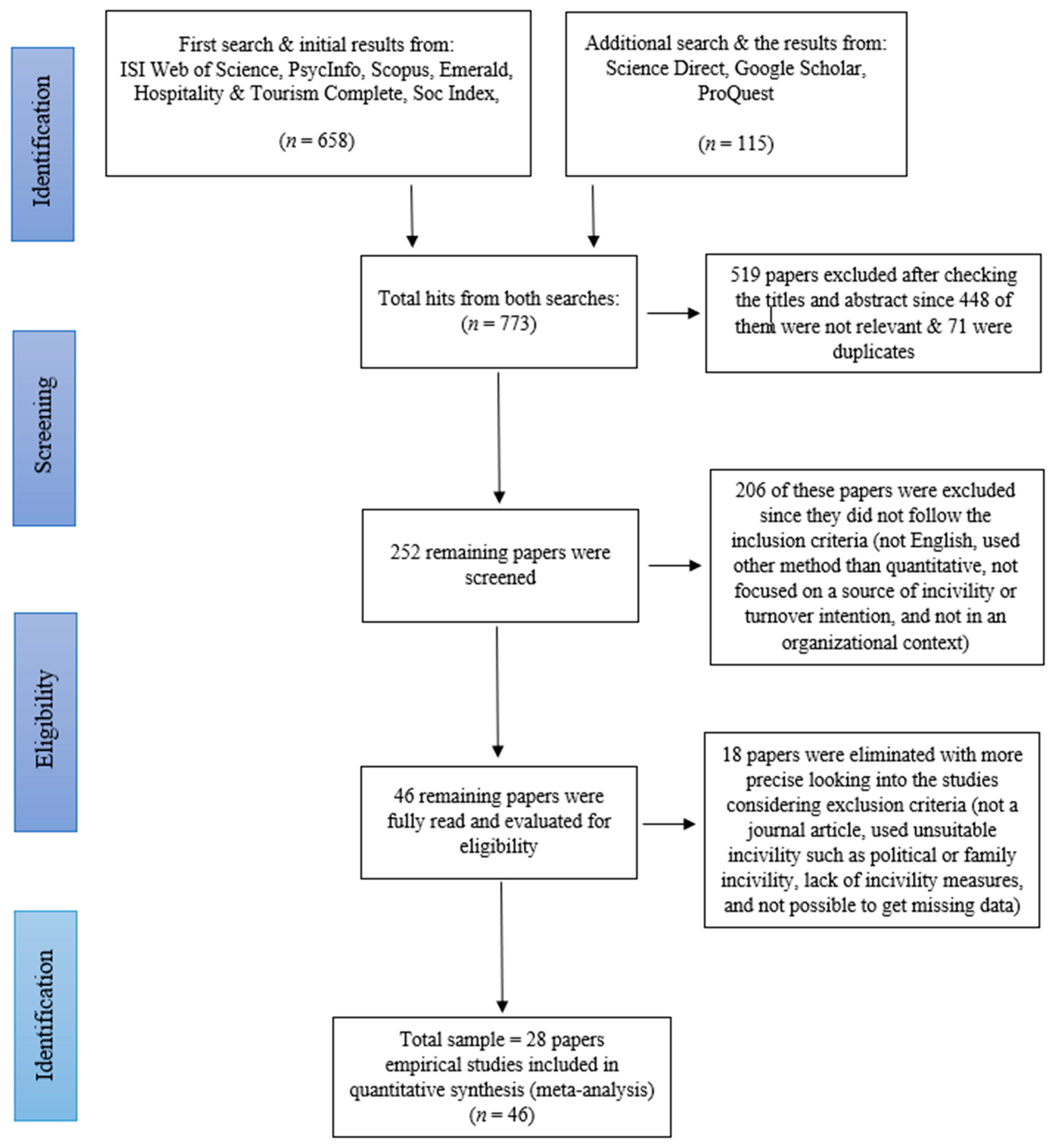

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Data Evaluation and Statistical Analyses

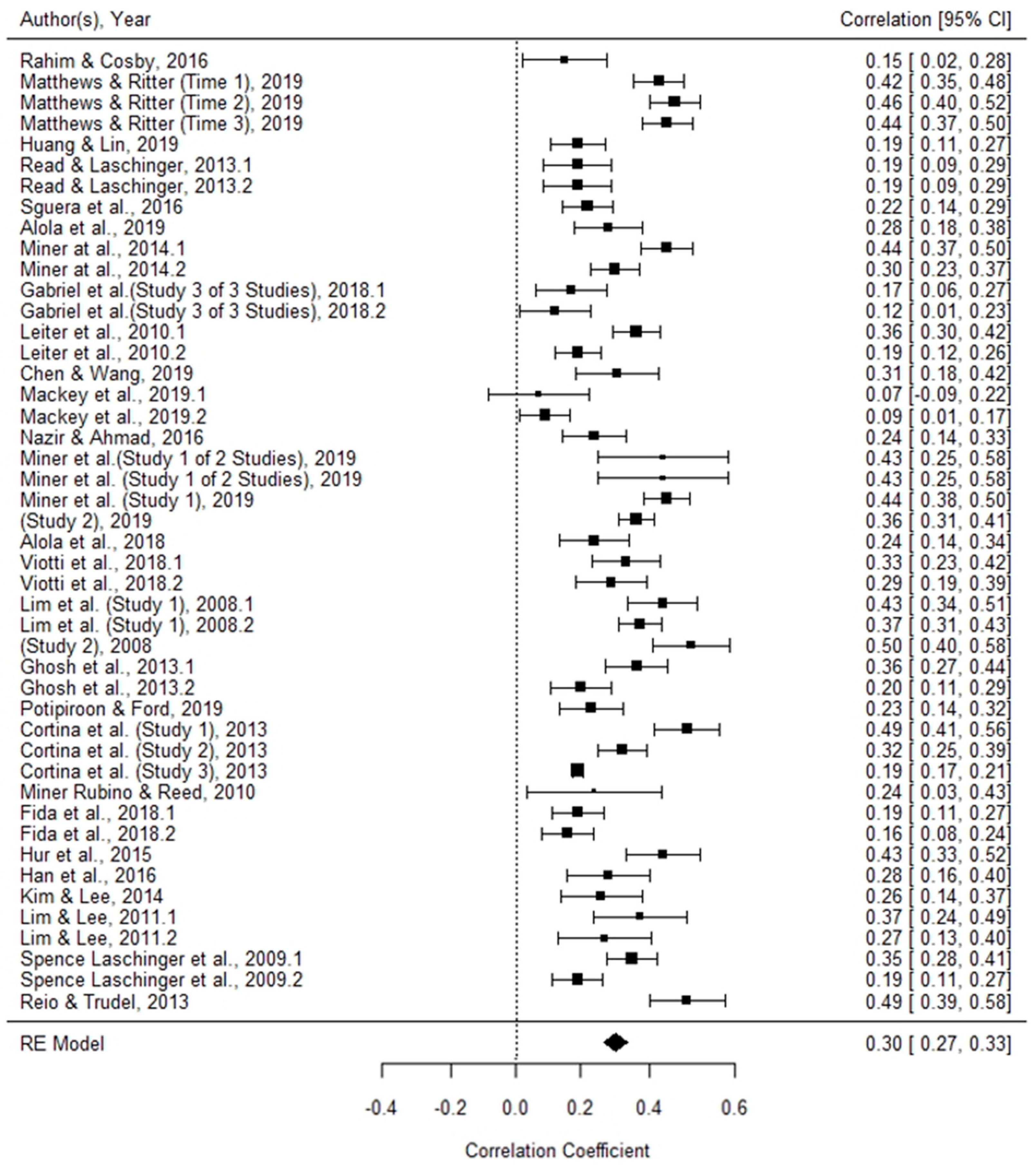

3. Results

3.1. Overall Effect

3.2. Sources of Incivility

3.3. Incivility Measures

3.4. Industries

3.5. Countries

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitation and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, H.-T.; Lin, C.-P. Assessing ethical efficacy, workplace incivility, and turnover intention: A moderated-mediation model. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2017, 13, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasli, H.; Namin, B.H.; Abubakar, A.M. Workplace incivility as a moderator of the relationships between polychronicity and job outcomes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1245–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Bonn, M.A.; Han, S.J.; Lee, K.H. Workplace incivility and its effect upon restaurant frontline service employee emotions and service performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2888–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A.; Ryan, A.M.; Lyons, B.J.; Ehrhart, M.G.; Wessel, J.L. The long road to employment: Incivility experienced by job seekers. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porath, C.; Pearson, C. The Price of Incivility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2013, 91, 114–121. Available online: https://hbr.org/2013/01/the-price-of-incivility (accessed on 20 August 2021). [PubMed]

- Cortina, L.M.; Kabat-Farr, D.; Leskinen, E.A.; Huerta, M.; Magley, V.J. Selective incivility as modern discrimination in organizations: Evidence and impact. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 1579–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, E.; Laschinger, H.K. Correlates of New Graduate Nurses’ Experiences of Workplace Mistreatment. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2013, 43, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiter, M.P.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Day, A.; Oore, D.G. The impact of civility interventions on employee social behavior, distress, and attitudes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1258–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortina, L.M. Unseen Injustice: Incivility as Modern Discrimination in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J. Personal and workgroup incivility: Impact on work and health outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, C.M.; Andersson, L.M.; Porath, C.L. Workplace incivility. In Counterproductive Workplace Behavior: Investigations of Actors and Targets; Fox, S., Spector, P.E., Eds.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.M.; Pearson, C.M. Tit for Tat? The Spiraling Effect of Incivility in the Workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Cortina, L.M. Interpersonal Mistreatment in the Workplace: The Interface and Impact of General Incivility and Sexual Harassment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J.; Williams, J.H.; Langhout, R.D. Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, C. The Cost of Bad Behavior: How Incivility Is Damaging Your Business and What to Do about It. Hum. Resour. Manag. Int. Dig. 2010, 18, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliter, M.; Jex, S.; Wolford, K.; McInnerney, J. How rude! Emotional labor as a mediator between customer incivility and employee outcomes. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner-Rubino, K.; Reed, W.D. Testing a Moderated Mediational Model of Workgroup Incivility: The Roles of Organizational Trust and Group Regard. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 3148–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.L.; Pearson, C.M. Emotional and Behavioral Responses to Workplace Incivility and the Impact of Hierarchical Status. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, E326–E357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, J.D.; Bishoff, J.D.; Daniels, S.R.; Hochwarter, W.A.; Ferris, G.R. Incivility’s Relationship with Workplace Outcomes: Enactment as a Boundary Condition in Two Samples. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 155, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, R.A.; Ritter, K.-J. Applying adaptation theory to understand experienced incivility processes: Testing the repeated exposure hypothesis. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alola, U.V.; Olugbade, O.A.; Avci, T.; Öztüren, A. Customer incivility and employees’ outcomes in the hotel: Testing the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 29, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M.; Kim, B.-S.; Park, S.-J. The Relationship between Coworker Incivility, Emotional Exhaustion, and Organizational Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. 2014, 25, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.; Cosby, D.M. A model of workplace incivility, job burnout, turnover intentions, and job performance. J. Manag. Dev. 2016, 35, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.J.; Bonn, M.A.; Cho, M. The relationship between customer incivility, restaurant frontline service employee burnout and turnover intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potipiroon, W.; Ford, M.T. Relational costs of status: Can the relationship between supervisor incivility, perceived support, and follower outcomes be exacerbated? J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 92, 873–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-T.; Wang, C.-H. Incivility, satisfaction and turnover intention of tourist hotel chefs. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2034–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, K.N.; Pesonen, A.D.; Smittick, A.L.; Seigel, M.L.; Clark, E.K. Does being a mom help or hurt? Workplace incivility as a function of motherhood status. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sguera, F.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Huy, Q.N.; Boss, R.W.; Boss, D.S. Curtailing the harmful effects of workplace incivility: The role of structural demands and organization-provided resources. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 95–96, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kim, W.G.; Zhao, X. Multilevel model of management support and casino employee turnover intention. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, A.; Lengler, J.; Aguzzoli, R. Staff turnover in hotels: Exploring the quadratic and linear relationships. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, J.D.; Kelly, F.; Arora, S.; Smith, H.L. The shocking cost of turnover in health care. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, J.I.; Allen, D.G.; Bosco, F.A.; McDaniel, K.R.; Pierce, C.A. Meta-Analytic Review of Employee Turnover as a Predictor of Firm Performance. J. Manag. 2011, 39, 573–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.P. High-Involvement Work Practices, Turnover, and Productivity: Evidence from New Zealand. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychol. Rev. 1985, 92, 548–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huesmann, L.R. Psychological Processes Promoting the Relation Between Exposure to Media Violence and Aggressive Behavior by the Viewer. J. Soc. Issues 1986, 42, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective Events Theory. Res. Organ. Behav. 1996, 18, 1–74. Available online: https://web.mit.edu/curhan/www/docs/Articles/15341_Readings/Affect/AffectiveEventsTheory_WeissCropanzano.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory, 1. Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs. 1977. Available online: http://www.asecib.ase.ro/mps/Bandura_SocialLearningTheory.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- Pearson, C.M.; Andersson, L.M.; Wegner, J.W. When Workers Flout Convention: A Study of Workplace Incivility. Hum. Relat. 2001, 54, 1387–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.L.; Erez, A. Does Rudeness Really Matter? The Effects of Rudeness on Task Performance and Helpfulness. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reio, T.G., Jr.; Ghosh, R. Antecedents and outcomes of workplace incivility: Implications for human resource development research and practice. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2009, 20, 237–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, C.M.; Andersson, L.M.; Porath, C.L. Assessing and attacking workplace incivility. Organ. Dyn. 2000, 29, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilpzand, P.; de Pater, I.E.; Erez, A. Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 37, S57–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.L.; Foulk, T.; Erez, A. How incivility hijacks performance. Organ. Dyn. 2015, 44, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliter, M.; Sliter, K.; Jex, S. The employee as a punching bag: The effect of multiple sources of incivility on employee withdrawal behavior and sales performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 33, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-Q.; Liu, C.; Nauta, M.M.; Caughlin, D.E.; Spector, P.E. Be Mindful of What You Impose on Your Colleagues: Implications of Social Burden for Burdenees’ Well-being, Attitudes and Counterproductive Work Behaviour. Stress Health 2014, 32, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, K.; Torkelson, E.; Bäckström, M. Models of Workplace Incivility: The Relationships to Instigated Incivility and Negative Outcomes. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 920239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M.P.; Price, S.L.; Laschinger, H.K.S. Generational differences in distress, attitudes and incivility among nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 970–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Leiter, M.; Day, A.; Gilin, D. Workplace empowerment, incivility, and burnout: Impact on staff nurse recruitment and retention outcomes. J. Nurs. Manag. 2009, 17, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoresen, C.J.; Kaplan, S.A.; Barsky, A.P.; Warren, C.R.; De Chermont, K. The Affective Underpinnings of Job Perceptions and Attitudes: A Meta-Analytic Review and Integration. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 914–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, W.H.; Horner, S.O.; Hollingsworth, A.T. An evaluation of precursors of hospital employee turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 1978, 63, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Min, H. Turnover intention in the hospitality industry: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, B. Multilevel relationships between organizational-level incivility, justice and intention to stay. Work. Stress 2010, 24, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.S. Job and career satisfaction and turnover intentions of newly graduated nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2011, 20, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J. Patterns and profiles of response to incivility in the workplace. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viotti, S.; Converso, D.; Hamblin, L.E.; Guidetti, G.; Arnetz, J.E. Organisational efficiency and co-worker incivility: A cross-national study of nurses in the USA and Italy. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 26, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Scollon, C.N. Beyond the Hedonic Treadmill: Revising the Adaptation Theory of Well-Being. In The Science of Well-Being; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S. Hedonic Adaptation to Positive and Negative Experiences. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping; Folkman, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 200–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Rothstein, H.R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furunes, T. Reflections on systematic reviews: Moving golden standards? Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 19, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.S.; Butts, M.M.; Yuan, Z.; Rosen, R.L.; Sliter, M.T. Further understanding incivility in the workplace: The effects of gender, agency, and communion. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 362–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, T.; Ungku, U.N.B. Interrelationship of incivility, cynicism and turnover intention. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2016, 6, 146–154. [Google Scholar]

- Miner, K.N.; January, S.C.; Dray, K.K.; Carter-Sowell, A.R. Is it always this cold? Chilly interpersonal climates as a barrier to the well-being of early-career women faculty in STEM. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2019, 38, 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, K.N.; Smittick, A.L.; He, Y.; Costa, P.L. Organizations Behaving Badly: Antecedents and Consequences of Uncivil Workplace Environments. J. Psychol. 2019, 153, 528–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alola, U.V.; Avci, T.; Ozturen, A. Organization Sustainability through Human Resource Capital: The Impacts of Supervisor Incivility and Self-Efficacy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Reio, T.G.; Bang, H. Reducing turnover intent: Supervisor and co-worker incivility and socialization-related learning. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2013, 16, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fida, R.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Leiter, M.P. The protective role of self-efficacy against workplace incivility and burnout in nursing. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2018, 43, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Lee, S. Women Sales Personnel’s Emotion Management: Do Employee Affectivity, Job Autonomy, and Customer Incivility Affect Emotional Labor? J. Asian Women 2014, 30, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Lee, A. Work and nonwork outcomes of workplace incivility: Does family support help? J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reio, T.G.; Trudel, J. Workplace Incivility and Conflict Management Styles: Predicting job performance, organizational com-mitment and turnover intent. International Journal of Adult Vocational Education and Technology (IJAVET). Int. J. Adult Vocat. Educ. Technol. 2013, 4, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting Meta-Analyses inRwith themetaforPackage. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, H.R.; Sutton, A.J.; Borenstein, M. (Eds.) Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, C.B.; Mazumdar, M. Operating Characteristics of a Rank Correlation Test for Publication Bias. Biometrics 1994, 50, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana, D.S. From pre-registration to publication: A non-technical primer for conducting a meta-analysis to synthesize correlational data. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2019; Available online: http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Sorge, A.; Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Adm. Sci. Q. 1983, 28, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S.W.; Hunter, J.E.; Schmidt, F.L. Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1991, 86, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliter, M.T.; Pui, S.Y.; Sliter, K.A.; Jex, S.M. The differential effects of interpersonal conflict from customers and coworkers: Trait anger as a moderator. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlaghimofrad, A.; Farmanesh, P. The association between interpersonal conflict, turnover intention and knowledge hiding: The mediating role of employee cynicism and moderating role of emotional intelligence. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernaus, T.; Aleksic, A.; Klindžić, M. Organizing for Competitiveness—Structural and Process Characteristics of Organizational Design. Contemp. Econ. 2013, 7, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Becher, T.; Trowler, P. Academic Tribes and Territories: Intellectual Enquiry and the Culture of Disciplines; McGraw-Hill International: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Serenko, A.; Bontis, N. Understanding counterproductive knowledge behavior: Antecedents and consequences of intra-organizational knowledge hiding. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 1199–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Raver, J.L.; Nishii, L.; Leslie, L.M.; Lun, J.; Lim, B.C.; Duan, L.; Almaliach, A.; Ang, S.; Arnadottir, J.; et al. Differences Between Tight and Loose Cultures: A 33-Nation Study. Science 2011, 332, 1100–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutgen-Sandvik, P.; Tracy, S.J.; Alberts, J.K. Burned by bullying in the American workplace: Prevalence, perception, degree and impact. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 837–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günsoy, C. Rude bosses versus rude subordinates: How we respond to them depends on our cultural background. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2019, 31, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J.; Heine, S.J.; Norenzayan, A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 2010, 33, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Peng, Y.; Geimer, J.; Sharp, O.; Jex, S. The multidimensionality of workplace incivility: Cross-cultural evidence. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2019, 26, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, R.; Ismail, I.R. Workplace incivility and knowledge hiding behavior: Does personality matter? J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2018, 5, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Xing, W.; Lizarondo, L.; Guo, M.; Hu, Y. Nursing students’ experiences with faculty incivility in the clinical education context: A qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, M.; Gelfand, M.J.; Hanges, P.J. Cultural Tightness–Looseness and Perceptions of Effective Leadership. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2015, 47, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

| Authors | Year | Journal | Country | Sample | Sample Size (n) | Correlation (r) | Type of Incivility | Incivility Measurement | Employees’ Outcome | Industry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rahim and Cosby | 2016 | Journal of Management Development | U.S. | Employed undergraduate Business students + Colleagues+ Supervisors | 223 | 0.15 | Coworker Incivility | WIS | Turnover Intention | Other |

| 2 | Matthews and Ritter (Time 1) | 2019 | Journal of occupational health psychology | U.S. | Working adults | 625 | 0.42 | Supervisor or Coworker Incivility | WIS | Turnover Intention | Other |

| 3 | (Time 2) | 0.46 | |||||||||

| 4 | (Time 3) | 0.44 | |||||||||

| 5 | Huang and Lin | 2019 | Review of Managerial Science | Taiwan | High-tech and Banking Ind. employees | 512 | 0.19 | Coworker Incivility | WIS | Turnover Intention | Other |

| 6 | Read and Laschinger | 2013 | The Journal of Nursing Administration (JONA) | Canada | New graduate nurses | 342 | 0.19 | Supervisor Incivility | WIS | Job Turnover | Healthcare Industry |

| 7 | 0.19 | Coworker Incivility | |||||||||

| 8 | Sguera et al. | 2016 | Journal of Vocational Behavior | U.S. | Nurses working in a public research hospital | 618 | 0.22 | Coworker Incivility | Modified WIS | Turnover Intention | Healthcare Industry |

| 9 | Alola et al. | 2019 | Tourism Management Perspectives | Nigeria | Customer-contact employees in 4- and 5-star hotels | 328 | 0.28 | Customer Incivility | 6 items from Cho, et al. (2016) | Turnover Intention | Hospitality Industry |

| 10 | Miner et al. | 2014 | Journal of Occupational Health Psychology | U.S. | Law school faculty members (Women) | 594 | 0.44 | Coworker Incivility | WIS | Turnover Intention | Academic work environment |

| 11 | Law school faculty members (Men) | 640 | 0.3 | ||||||||

| 12 | Gabriel et al. (Study 3) | 2018 | Journal of Applied Psychology | U.S. | Junior and senior undergraduate business students (Women) | 319 | 0.17 | Coworker Incivility | WIS | Turnover Intention | Other |

| 13 | Junior and senior undergraduate business students (Men) | 0.12 | |||||||||

| 14 | Leiter et al. | 2010 | Journal of Nursing management | Canada | Nurses | 729 | 0.36 | Supervisor Incivility | WIS | Turnover Intention | Healthcare Industry |

| 15 | 0.19 | Coworker Incivility | |||||||||

| 16 | Chen and Wang | 2019 | International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management | Taiwan | Tourist hotel chefs | 226 | 0.306 | Supervisor and Coworker Incivility | WIS | Turnover Intention | Hospitality Industry |

| 17 | Mackey et al. | 2019 | Journal of Business Ethics | U.S. | Manufacturing employees | 156 | 0.07 | Coworker incivility | Modified versionof Spector and Jex’s (1998) 4-item scale | Turnover Intention | Other |

| 18 | Full-time employees | 620 | 0.09 | ||||||||

| 19 | Nazir and Ungku | 2016 | International Review of Management and Marketing | Pakistan | Nurses in 10 selected healthcare settings | 395 | 0.24 | Supervisor and Coworker incivility | WIS | Turnover Intention | Healthcare Industry |

| 20 | Miner et al. (Study 1) | 2019a | Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion: An International Journal | U.S. | Early-career STEM faculty (Women) | 96 | 0.43 | Coworker Incivility | WIS | Turnover Intention | Academic work environment |

| 21 | Early-career STEM faculty (Men) | 0.43 | |||||||||

| 22 | Miner et al. (Study 1) | 2019b | The Journal of psychology | U.S. | Faculty members of different departments at a large university | 742 | 0.44 | Coworker Incivility | WIS | Turnover Intention | Academic work environment |

| 23 | (Study 2) | A nation-wide sample of Law School Faculty members | 1300 | 0.36 | |||||||

| 24 | Alola et al. | 2018 | Sustainability | Nigeria | Customer contact employees of 4- and 5-star Hotels | 329 | 0.24 | Supervisor Incivility | Five items from Cho et al. (2016) | Turnover Intention | Hospitality Industry |

| 25 | Viotti et al. | 2018 | Journal of nursing management | U.S. | Nurses | 341 | 0.33 | Coworker Incivility | Four-item scale adapted bySliter et al. (2012) | Intention to Leave | Healthcare Industry |

| 26 | Italy | 313 | 0.29 | ||||||||

| 27 | Lim et al. (Study 1) | 2008 | Journal of applied psychology | U.S. | All employees of the Federal Courts of one of the larger circuits (Men) | 325 | 0.43 | Supervisor and Coworker Incivility | WIS | Turnover Intention | Other |

| 28 | All employees of the Federal Courts of one of the larger circuits (Women) | 833 | 0.37 | ||||||||

| 29 | (Study 2) | Employees of a midwestern municipality | 271 | 0.5 | Coworker Incivility | Expanded 12 items WIS | |||||

| 30 | Ghosh et al. | 2013 | Human Resource Development International | U.S. | Full-time employees from different organizations | 420 | 0.36 | Supervisor Incivility | Modified version of Reio’s (2011) based on WIS | Turnover Intention | Other |

| 31 | 0.2 | Coworker Incivility | Expanded 15 items WIS | ||||||||

| 32 | Potipiroon and Ford | 2019 | Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology | Thailand | Employees and their supervisors at a large public agency | 401 | 0.23 | Supervisor Incivility | WIS | Turnover Intention | Other |

| 33 | Cortina et al. (Study 1) | 2013 | Journal of Management | U.S. | City government municipality employees | 369 | 0.49 | Supervisor and Coworker Incivility | Expanded WIS | Turnover Intention | Other |

| 34 | (Study 2) | Law enforcement agency | 653 | 0.32 | Coworker Incivility | Expanded 20 items WIS | |||||

| 35 | (Study 3) | Military “active-duty members of the army” | 15497 | 0.19 | 10 items from Aggressive Experiences Scale by Glomb and Liao (2003) | ||||||

| 36 | Miner-Rubino and Reed | 2010 | Journal of Applied Social Psychology | U.S. | Employees of a property-management company | 90 | 0.24 | Supervisor and Coworker Incivility | Modified 8 items WIS | Turnover Intention | Other |

| 37 | Fida et al. | 2018 | Health care management review | Canada | Nurses | 596 | 0.19 | Coworker Incivility | The Straightforward Incivility Scale by Leiter & Day (2013) | Job Turnover | Healthcare Industry |

| 38 | 0.16 | Supervisor Incivility | |||||||||

| 39 | Hur et al. | 2015 | Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing and Service Industries | South Korea | Retail bank frontline employees | 286 | 0.43 | Coworker Incivility | Four items adapted from Sliter, et al. (2012) | Turnover Intention | Other |

| 40 | Han et al. | 2016 | International Journal of Hospitality Management | U.S. | Frontline service employees in independent Florida-based restaurants | 228 | 0.28 | Customer Incivility | 14 items adopted from Burnfield et al. (2004) | Turnover Intention | Hospitality Industry |

| 41 | Kim and Lee | 2014 | Asian Women | South Korea | Women who work in sales service in clothing industry | 239 | 0.26 | Customer Incivility | Original scale developed by Wilson and Holmvall (2013) | Turnover Intention | Other |

| 42 | Lim and Lee | 2011 | Journal of Occupational Health Psychology | Singapore | Full-time employees from various organizations | 180 | 0.37 | Supervisor Incivility | Modified WIS | Intent to Quit | Other |

| 43 | 0.27 | Coworker Incivility | |||||||||

| 44 | Spence Laschinger et al. | 2009 | Journal of nursing management | Canada | Nurses | 612 | 0.347 | Supervisor Incivility | WIS | Turnover Intentions | Healthcare Industry |

| 45 | 0.19 | Coworker Incivility | |||||||||

| 46 | Reio and Trudel | 2013 | International Journal of Adult Vocational Education and Technology (IJAVET) | U.S. | Healthcare (143) + Manufacturing employees (127) | 270 | 0.49 | Supervisor and Coworker Incivility | WIS | Turnover Intention | Other |

| Type of Incivility | n | Estimate | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept/coworker incivility | 25 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.32 | <0.0001 |

| Supervisor incivility | 8 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.11 | 0.745 |

| Supervisor or coworker incivility | 1 | 0.17 | −0.05 | 0.40 | 0.136 |

| Supervisor and coworker incivility | 9 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.002 |

| Customer incivility | 3 | 0.005 | −0.14 | 0.15 | 0.946 |

| Type of Incivility | n | Estimate | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept/healthcare sector | 12 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.31 | <0.0001 |

| Academic sector | 6 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.005 |

| Hospitality sector | 4 | 0.03 | −0.10 | 0.17 | 0.618 |

| Other | 24 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.16 | 0.082 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Namin, B.H.; Øgaard, T.; Røislien, J. Workplace Incivility and Turnover Intention in Organizations: A Meta-Analytic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010025

Namin BH, Øgaard T, Røislien J. Workplace Incivility and Turnover Intention in Organizations: A Meta-Analytic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleNamin, Boshra H., Torvald Øgaard, and Jo Røislien. 2022. "Workplace Incivility and Turnover Intention in Organizations: A Meta-Analytic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010025

APA StyleNamin, B. H., Øgaard, T., & Røislien, J. (2022). Workplace Incivility and Turnover Intention in Organizations: A Meta-Analytic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010025