Parents’ Perceptions on Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity among Schoolchildren: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Ethical Issues

2.3. Selection of Schools and Informants

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

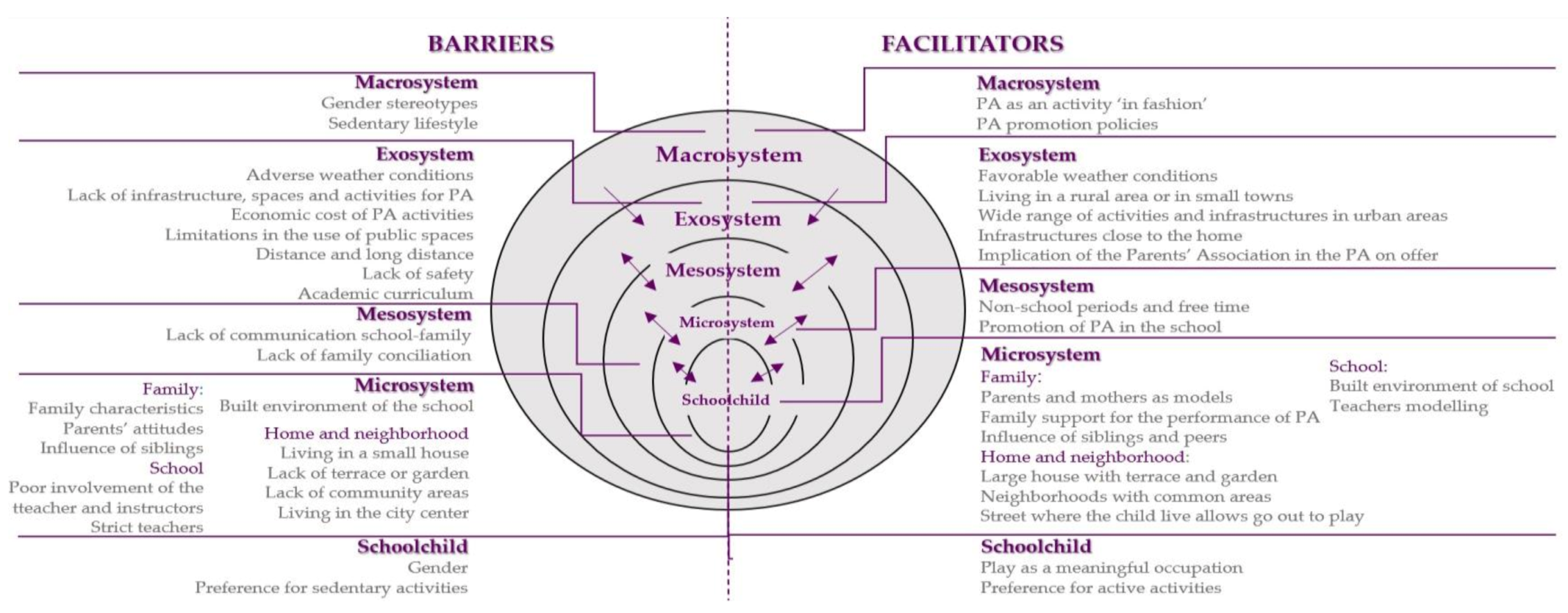

3. Results

3.1. Barriers to Physical Activity in Schoolchildren

3.1.1. Individual Factors

3.1.2. Microsystem

Family Factors Limiting Physical Activity

Educational Factors That Limit Physical Activity

Home and Neighborhood Factors That Make PA Difficult

3.1.3. Mesosystem

Lack of Communication between the School and the Family

Lack of Family Conciliation

3.1.4. Exosystem

Barriers in the Community and in the Physical and Built Environment That Made Physical Activity Difficult

Factors in the Academic Curriculum That Limited Physical Activity

Influence of the Media

3.1.5. Macrosystem

3.2. Physical Activity Facilitators for Schoolchildren

3.2.1. Individual Factors

3.2.2. Microsystem

Family Factors Promoting Physical Activity

Influence of Peers

School Factors Promoting Physical Activity

Household and Neighborhood Factors That Encouraged Physical Activity

3.2.3. Mesosystem

Holiday Periods and Free Time

The School as a Setting for Conveying Values

3.2.4. Exosystem

Community Facilitators and the Physical and Built Environment Promoting Physical Activity

Organization of after School Activities Related to Physical Activity

3.2.5. Macrosystem

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garrido-Miguel, M.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Álvarez-Bueno, C.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; Moreno, L.A.; Ruiz, J.R.; Ahrens, W.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity in European children from 1999 to 2016: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics 2019, 173, e192430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, S.; Lorenzo, L.; Ribes, C.; Homs, C. Informe Estudio PASOS 2019; Gasol Foundation: Sant Boi de Llobregat, Barcelona, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative: HIGHLIGHTS 2015–17. 2018. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/publications/2018/childhood-obesity-surveillance-initiative-cosi-factsheet.-highlights-2015-17-2018 (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Larrañaga, N.; Amiano, P.; Arrizabalaga, J.; Bidaurrazaga, J.; Gorostiza, E. Prevalence of obesity in 4–18-year-old population in the Basque Country, Spain. Obes. Rev. 2007, 8, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Miguel, M.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Herráiz-Adillo, Á.; Martínez-Hortelano, J.A.; Soriano-Cano, A.; Díez-Fernández, A.; Solera-Martínez, M.; Sánchez-López, M. Obesity and thinness prevalence trends in Spanish schoolchildren: Are they two convergent epidemics? Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, A.C.; Perrin, E.M.; Moss, L.A.; Skelton, J.A. Cardiometabolic Risks and Severity of Obesity in Children and Young Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1307–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardinha, L.B.; Santos, D.A.; Silva, A.M.; Grontved, A.; Andersen, L.B.; Ekelund, U. A Comparison between BMI, Waist Circumference, and Waist-To-Height Ratio for Identifying Cardio-Metabolic Risk in Children and Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Espinosa, N.; Diez-Fernandez, A.; Sanchez-Lopez, M.; Rivero-Merino, I.; Lucas-De La Cruz, L.; Solera-Martinez, M.; Martinez-Vizcaino, V.; Movi-Kids, G. Prevalence of high blood pressure and association with obesity in Spanish schoolchildren aged 4–6 years old. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kelly, A.S. Review of Childhood Obesity: From Epidemiology, Etiology, and Comorbidities to Clinical Assessment and Treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Bueno, C.; Pesce, C.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Sánchez-López, M.; Garrido-Miguel, M.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Academic Achievement and Physical Activity: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Bueno, C.; Pesce, C.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Sanchez-Lopez, M.; Martinez-Hortelano, J.A.; Martinez-Vizcaino, V. The Effect of Physical Activity Interventions on Children’s Cognition and Metacognition: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, H.A.; Dam, R.; Hassan, L.; Jenkins, D.; Buchan, I.; Sperrin, M. Post-2000 growth trajectories in children aged 4–11 years: A review and quantitative analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 14, 100834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland-Cachera, M.-F.; Deheeger, M.; Bellisle, F.; Sempe, M.; Guilloud-Bataille, M.; Patois, E. Adiposity rebound in children: A simple indicator for predicting obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1984, 39, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.W.; Grant, A.M.; Goulding, A.; Williams, S.M. Early adiposity rebound: Review of papers linking this to subsequent obesity in children and adults. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2005, 8, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolland-Cachera, M.; Deheeger, M.; Maillot, M.; Bellisle, F. Early adiposity rebound: Causes and consequences for obesity in children and adults. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.M.; Goulding, A. Patterns of growth associated with the timing of adiposity rebound. Obesity 2009, 17, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, R.; Adams, J.; van Sluijs, E.M. Are school-based physical activity interventions effective and equitable? A meta-analysis of cluster randomized controlled trials with accelerometer-assessed activity. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carson, V.; Lee, E.Y.; Hewitt, L.; Jennings, C.; Hunter, S.; Kuzik, N.; Stearns, J.A.; Unrau, S.P.; Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.; et al. Systematic Review of the Relationships between Physical Activity and Health Indicators in the Early Years (0–4 Years); BMC Public Health: London, UK, 2017; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Pate, R.R.; Hillman, C.H.; Janz, K.F.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Powell, K.E.; Torres, A.; Whitt-Glover, M.C. Physical Activity and Health in Children Younger than 6 Years: A Systematic Review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1282–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep for Children under 5 Years Age; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, S.; Reilly, J. Global matrix 3.0 physical activity report card grades for children and youth: Results and analysis from 49 countries. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, S251–S273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, P.S.; Saelens, B.E.; Copeland, K. A comparison of parent and child-care provider’s attitudes and perceptions about preschoolers’ physical activity and outdoor time. Child Care Health Dev. 2017, 43, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, A.; Townshend, T. Obesogenic environments: Exploring the built and food environments. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 2006, 126, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.; Egger, G.; Raza, F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: The development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev. Med. 1999, 29, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Report of the CommissiEnding Childhood Obesity: Implementatiplan: Executive summary; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Environments in developmental perspective: Theoretical and operational models. PsycNET 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, D.E.; Froelicher, E.S.; Waters, C.M.; Carrieri-Kohlman, V. Parental influence on models of primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in children. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2003, 2, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, T.M.; Jago, R.; Baranowski, T. Engaging Parents to Increase Youth Physical Activity A Systematic Review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, J.J.; Hughes, A.R.; Gillespie, J.; Malden, S.; Martin, A. Physical activity interventions in early life aimed at reducing later risk of obesity and related non-communicable diseases: A rapid review of systematic reviews. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, G.F.; Goodred, J.K.; Jago, R.; Sebire, S.J.; Lucas, P.J.; Fox, K.R.; Stewart-Brown, S.; Turner, K.M. Parents’ views on child physical activity and their implications for physical activity parenting interventions: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatrics 2012, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowles, R.; O’Sullivan, M. Rhetoric and reality: The role of the teacher in shaping a school sport programme. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2012, 17, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Craemer, M.; De Decker, E.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Deforche, B.; Vereecken, C.; Duvinage, K.; Grammatikaki, E.; Iotova, V.; Fernandez-Alvira, J.M.; Zych, K.; et al. Physical activity and beverage consumption in preschoolers: Focus groups with parents and teachers. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Decker, E.; De Craemer, M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Wijndaele, K.; Duvinage, K.; Androutsos, O.; Iotova, V.; Lateva, M.; Alvira, J.M.F.; Zych, K.; et al. Influencing Factors of Sedentary Behavior in European Preschool Settings: An Exploration Through Focus Groups With Teachers. J. Sch. Health 2013, 83, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, G.M.; Higgs, J.; Hardy, L.L.; Baur, L.A. What do parents and preschool staff tell us about young children’s physical activity: A qualitative study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, M.J.; Jago, R.; Sebire, S.J.; Kesten, J.M.; Pool, L.; Thompson, J.L. The influence of friends and siblings on the physical activity and screen viewing behaviours of children aged 5-6 years: A qualitative analysis of parent interviews. BMJ Open 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyler, A.; Baldwin, J.; Carnoske, C.; Nickelson, J.; Troped, P.; Steinman, L.; Pluto, D.; Litt, J.; Evenson, K.; Terpstra, J.; et al. Parental involvement in active transport to school initiatives: A multi-site case study. Am. J. Health Educ. 2008, 39, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessler, K.L. Physical activity behaviors of rural preschoolers. Pediatr. Nurs. 2009, 35, 246–253. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, J.D.; He, M.; Bouck, L.M.S.; Tucker, P.; Pollett, G.L. Preschoolers’ physical activity behaviours: parents’ perspectives. Can. J. Public Health 2005, 96, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, K.C.; Holt, N.L. Parents’ Perspectives on the Benefits of Sport Participation for Young Children. Sport Psychol. 2014, 28, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, P.; van Zandvoort, M.M.; Burke, S.M.; Irwin, J.D. The influence of parents and the home environment on preschoolers’ physical activity behaviours: A qualitative investigation of childcare providers’ perspectives. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuniga, K.D. From barrier elimination to barrier negotiation: A qualitative study of parents’ attitudes about active travel for elementary school trips. Transp. Policy 2012, 20, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, J.; Sebire, S.J.; Jago, R. “He’s probably more Mr. sport than me”—A qualitative exploration of mothers’ perceptions of fathers’ role in their children’s physical activity. BMC Pediatrics 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesch, M.H.; Wentz, E.E.; Rosenblum, K.L.; Appugliese, D.P.; Miller, A.L.; Lumeng, J.C. “You’ve got to settle down!”: Mothers’ perceptions of physical activity in their young children. BMC Pediatrics 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Arcury, T.A.; Trejo, G.; Quandt, S.A. Latino mothers in farmworker families’ beliefs about preschool children’s physical activity and play. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2016, 18, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Copeland, K.A.; Kendeigh, C.A.; Saelens, B.E.; Kalkwarf, H.J.; Sherman, S.N. Physical activity in child-care centers: Do teachers hold the key to the playground? Health Educ. Res. 2012, 27, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellows, L.; Anderson, J.; Gould, S.M.; Auld, G. Formative research and strategic development of a physical activity component to a social marketing campaign for obesity prevention in preschoolers. J. Community Health 2008, 33, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucaides, C.A.; Chedzoy, S.M. Factors influencing Cypriot children’s physical activity levels. Sport Educ. Soc. 2005, 10, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkley, T.; McCann, J.R. Mothers’ and father’s perceptions of the risks and benefits of screen time and physical activity during early childhood: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, A.C.; Moura Arruda, C.A.; Tavares Machado, M.M.; De Andrade, G.P.; Greaney, M.L. Exploring how Brazilian immigrant mothers living in the USA obtain information about physical activity and screen time for their preschool-aged children: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.A.; Zarrett, N.; Cook, B.S.; Egan, C.; Nesbitt, D.; Weaver, R.G. Movement integration in elementary classrooms: Teacher perceptions and implications for progrAm. planning. Eval. Program Plan. 2017, 61, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Decker, E.; De Craemer, M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Wijndaele, K.; Duvinage, K.; Koletzko, B.; Grammatikaki, E.; Iotova, V.; Usheva, N.; Fernández-Alvira, J.M.; et al. Influencing factors of screen time in preschool children: An exploration of parents’ perceptions through focus groups in six European countries. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Vizcaino, V.; Mota, J.; Solera-Martínez, M.; Notario-Pacheco, B.; Arias-Palencia, N.; García-Prieto, J.C.; González-García, A.; Álvarez-Bueno, C.; Sánchez-López, M. Rationale and methods of a randomised cross-over cluster trial to assess the effectiveness of MOVI-KIDS on preventing obesity in pre-schoolers. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-López, M.; Pardo-Guijarro, M.J.; Campo, D.G.-D.d.; Silva, P.; Martínez-Andrés, M.; Gulías-González, R.; Díez-Fernández, A.; Franquelo-Morales, P.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Physical activity intervention (Movi-Kids) on improving academic achievement and adiposity in preschoolers with or without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2015, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Pozuelo-Carrascosa, D.P.; García-Prieto, J.C.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Solera-Martínez, M.; Garrido-Miguel, M.; Díez-Fernández, A.; Ruiz-Hermosa, A.; Sánchez-López, M. Effectiveness of a school-based physical activity intervention on adiposity, fitness and blood pressure: MOVI-KIDS study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Grounded theory methodology. Handb. Qual. Res. 1994, 17, 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. Discovery Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, P.; Stewart, K.; Treasure, E.; Chadwick, B. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. Br. Dent. J. 2008, 204, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeije, H.R.; van Wesel, F.; Alisic, E. Making a difference: Towards a method for weighing the evidence in a qualitative synthesis. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2011, 17, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla-García, M.Á.; López-Suárez, A.D. Ejemplificación del proceso metodológico de la teoría fundamentada. Cinta Moebio 2016, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirela, J.; Blanco, N.; Nones, N. El modelo de la teoría fundamentada de Glaser y Strauss: Una alternativa para el abordaje cualitativo de lo social. Omnia 2004, 1, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Recomendaciones Mundiales Sobre Actividad Física para la Salud; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, A.; Lynch, H. Understanding a child’s conceptualisation of well-being through an exploration of happiness: The centrality of play, people and place. J. Occup. Sci. 2018, 25, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzog, D.; Cermak, S.; Bar-Shalita, T. Sensory modulation, physical activity and participation in daily occupations in young children. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 86, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larouche, R.; Mire, E.F.; Belanger, K.; Barreira, T.V.; Chaput, J.P.; Fogelholm, M.; Hu, G.; Lambert, E.V.; Maher, C.; Maia, J.; et al. Relationships Between Outdoor Time, Physical Activity, Sedentary Time, and Body Mass Index in Children: A 12-Country Study. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2019, 31, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arundell, L.; Fletcher, E.; Salmon, J.; Veitch, J.; Hinkley, T. A systematic review of the prevalence of sedentary behavior during the after-school period among children aged 5–18 years. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Andrés, M.; Bartolomé-Gutiérrez, R.; Rodríguez-Martín, B.; Pardo-Guijarro, M.J.; Garrido-Miguel, M.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Barriers and Facilitators to Leisure Physical Activity in Children: A Qualitative Approach Using the Socio-Ecological Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcuna, V.A.; Rodríguez-Martín, B. Parents’ and Teachers’ Perceptions of Physical Activity in Schools: A Meta-Ethnography. J. Sch. Nurs. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, A.C.; Greaney, M.L.; Wallington, S.F.; Mesa, T.; Salas, C.F. A Review of Early Influences on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviors of Preschool-Age Children in High-Income Countries. J. Spec. Pediatric Nurs. Jspn 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigsby-Toussaint, D.S.; Chi, S.H.; Fiese, B.H. Where They Live, How They Play: Neighborhood Greenness and Outdoor Physical Activity Among Preschoolers. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2011, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Lopez, M.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Alvarez-Bueno, C.; Ruiz-Hermosa, A.; Pozuelo-Carrascosa, D.P.; Diez-Fernandez, A.; Gutierrez-Diaz Del Campo, D.; Pardo-Guijarro, M.J.; Martinez-Vizcaino, V. Impact of a multicomponent physical activity intervention on cognitive performance: The MOVI-KIDS study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2019, 29, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haapala, E.; Väistö, J.; Lintu, N.; Westgate, K.; Ekelund, U.; Poikkeus, A.; Brage, S.; Lakka, T. Physical Activity and Sedentary Time in Relation to Academic Achievement in Children. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, K.; Hatzis, D.; Kavanagh, D.J.; White, K.M. Exploring Parents’ Beliefs About Their Young Child’s Physical Activity and Screen Time Behaviours. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2014, 24, 2638–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, T.M.; Cerin, E.; Hughes, S.O.; Robles, J.; Thompson, D.; Baranowski, T.; Lee, R.E.; Nicklas, T.; Shewchuk, R.M. What Hispanic parents do to encourage and discourage 3–5 years old children to be active: A qualitative study using nominal group technique. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesketh, K.R.; Lakshman, R.; van Sluijs, E.M.F. Barriers and facilitators to young children’s physical activity and sedentary behaviour: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative literature. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 987–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chau, C.K.; Ng, W.; Leung, T. A review on the effects of physical built environment attributes on enhancing walking and cycling activity levels within residential neighborhoods. Cities 2016, 50, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.A.; Clark, A.F.; Gilliland, J.A. Built environment influences of children’s physical activity: Examining differences by neighbourhood size and sex. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, T.L.; Hannon, J.C.; Webster, C.A.; Podlog, L. Classroom teachers’ experiences implementing a movement integration program: Barriers, facilitators, and continuance. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 66, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, R.D.; Webster, C.A.; Egan, C.A.; Nilges, L.; Brian, A.; Johnson, R.; Carson, R.L. Facilitators and Barriers to Movement Integration in Elementary Classrooms: A Systematic Review. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Hosking, J.; Woodward, A.; Witten, K.; MacMillan, A.; Field, A.; Baas, P.; Mackie, H. Systematic literature review of built environment effects on physical activity and active transport—An update and new findings on health equity. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, J.M.; Barrett, M.; Mayan, M.; Olson, K.; Spiers, J. Verification Strategies for Establishing Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2002, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Topic | Subtopic |

|---|---|

| Mothers’ and fathers’ experiences of physical activity | Regular physical activity. Physical activity practice during holidays. Self-perception. Motivation for physical activity. Value attached to physical activity |

| Fathers’ and mothers’ perceptions of their children’s physical activity | How time is spent. Type of activities carried out at home, in the community, and at school. Leisure versus work time. Meaning of being active versus being sedentary. Children’s self-management and attitude towards the type of activities undertaken. Parents’ expectations of their children’s activities. Determining factors in the choice of type of activity. Importance attributed to the activities carried out by the child throughout the day. |

| Family dynamics | Family factors that facilitate children’s physical activity. Family factors that hinder children’s physical activity. Type of activities carried out in the family. Parent modelling. |

| Facilitators and barriers of the physical and social environment as perceived by parents | The domestic environment: use of private space. Use of public and community space. Built environment and accessibility. Availability and use of public and private resources in the place where they live that promote physical activity.Perception of safety in public/private space.Influence of weather conditions.Social relationships and extra-familial influence. |

| Travel and type of transport | Places where the child usually travels. Active travel (on foot or by bicycle). Mode of transport used. Preferences in the choice of type of transport. |

| Material resources related to physical activity | Preferences in the use and availability of games, toys and sports materials. Children’s wishes versus parents’ wishes. Clothing and footwear. Factors influencing the purchase of equipment. |

| The role of the school in the physical activity of schoolchildren | Knowledge about the functioning and policies of the school. Perception of the involvement of the teaching and management team in promoting physical activity among children. Involvement of parents in decision-making about school activities. Level of satisfaction with the activities carried out by children at the school. Range of activities offered and management of extracurricular activities. |

| Strategies to promote physical activity among schoolchildren | Strategies parents are aware of to keep children active. Role of different social agents/responsibility for children’s physical activity. Areas for improvement at school, at home and in the community. Influences of policy, media, advertising, and marketing. Parent training strategies. Parents’ motivation as change-makers. |

| Participant´s Characteristics | Cuenca | Ciudad Real | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 25 | n = 21 | n = 46 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| <35 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| 35–45 | 20 | 16 | 36 |

| >45 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 3 | 8 | 11 |

| Female | 22 | 13 | 35 |

| Area | |||

| Rural | 11 | 13 | 24 |

| Urban | 14 | 8 | 22 |

| Educational level | |||

| No education | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Primary education | 6 | 9 | 15 |

| Secondary education | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| Intermediate vocational training | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Higher vocational training | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| High School diploma | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| University studies | 11 | 1 | 12 |

| Civil status | |||

| Single | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Married | 23 | 16 | 39 |

| Divorced | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Unmarried | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Widowed | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Employment status | |||

| Employee | 14 | 8 | 22 |

| Unemployed | 11 | 13 | 24 |

| Profession | |||

| Administrative | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Bank clerk | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Environmental agent | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Commercial agent | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Real estate agent | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Construction worker | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Housewife | 10 | 7 | 17 |

| Self-employed | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Teacher assistant | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Hotel and catering professional | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Teacher | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Health professional–social worker | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Sports worker | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Civil servant | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Pensioner | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Family unit | |||

| Mean number of children | 2.28 | 2.24 | 2.26 |

| Individual Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Subcategories | Code | Parents’ Verbalizations |

| Individual factors of schoolchildren that hinder their physical activity | Gender preferences | “And then the girls, they like dolls more” (M4, FG1). “I think that what they usually like the most is what she says, if they are girls they like dancing, if they are boys they like karate or football” (M3, FG2). | |

| Schoolchildren’s preference for sedentary activities | Quiet personality of schoolchildren | “...And the other one if it were up to her she would be lying on the couch all day, so I have to force her...” (M4, FG6). “...What happens is that, well, every child is a different world, so of the five that I have, none of them have turned out to be sporty. Since they were little I’ve been trying, but in the end, most of them have sedentary habits, at least three of them, and even if you’re on top of them and so on, it’s complicated, no, because no, not genetically, I don’t know, they must inherited it from their grandmothers” (F5, FG6). “...He’s more into books, he’s not into sport. You tell him let’s go running and pick up a book and he picks up a book” (M7, FG6). | |

| Children’s boredom | “Mine, she never knows what to play, they have everything, in the old days when we were little we didn’t have anything, they have video consoles or tablets or I don’t know what and all of a sudden as she tells you that she’s bored, that she doesn’t know what to play. Especially in the cold winter months. Now less so, because as soon as that happens, she says ’I get bored, I don’t know what to play’” (M1, FG1). “A lot of times they get bored, ’Oh, mum, I’m bored, I want to play I want to... let me have your mobile phone to play with the games on the mobile!’" (M2,FG8). | ||

| Preference for playing with mobile phones, computers, or video | “The first thing they do when they come into the house is pick up the tablet, sit on the sofa and put the TV on, even if they don’t watch it, but they put the TV on and the tablet. In winter especially, now they are more inclined to go downstairs to play and all that, but in winter it’s the television, and video games, the phone, the computer and so on” (M1, FG1). “...Everything, but come on, he also likes to play video games, if you leave him the tablet, the tablet, whenever I leave it, it also takes up his time and he likes it. When he sees the mobile phone lying around, he immediately goes to pick it up, to play games” (M7, FG7). “...And then a lot of video game consoles, we just... all the video game consoles they want and more, and that’s it” (M2, FG4). | ||

| Preference for watching TV | “...They get hooked and can spend two hours watching TV, which is nothing, and maybe they arrive just on time, and they want to continue watching TV at my house, but if you’ve been watching TV for two hours, I mean, as soon as you give them a little bit of TV, I notice that, I know, that it’s addiction to TV” (M5, FG1). | ||

| Microsystem | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Subcategories | Code | Parents’ Verbalizations |

| Family factors limiting physical activity | Family characteristics | Single-parent families | “I think we also have to differentiate which family group the child belongs to. Because there are four of us here, two of them are happily married, living with a couple and the other two are not, so I think the child, specifically in my case, I think the child demands both ways, don’t you? (M4, FG2). |

| Need for support from others in caring | “I think that yes, when parents are working, if you leave the person in charge, they can’t take them or bring them or go out with them, of course they do less physical activity than if you are with them” (M2, FG2). | ||

| Unemployed parents | “...There are many unemployed parents and I would also sign him up to I don’t know what, but that’s worth a lot, you can’t afford it” (F3, FG5). | ||

| Parents’ attitudes | Promoting academic achievement | “...’What did you do in Mathematics?’, or ’Did you have an exam?’, but if he tells me that he is going to take an exam in Physics, Physical Education, I don’t ask him ’How did you do?’ My child has got a ’B’ in gymnastics in all 3 assessments, well, and this time he says ’mummy, I got an ’A’’, and I say ’you have to get it in Maths or Spanish’, you know? yes, well, you have to get it in Spanish, because if you don’t get it in Spanish or Maths or a subject like that, I tend to get more angry” (M3, FG8). | |

| Parents decide what activities children do | “What I was saying is that they are induced, that right now if the mother says you go and do this, more than 7% will do it, because they will do it because, if the mother has said so, they will do it” (M2, FG5). | ||

| Mothers encourage quiet play and sedentary activities | “I don’t, I do activities because I like baking a lot, so if I think, well, let’s make a sponge cake! and in that, yes, they get involved, they help me, I pour the flour, I give them the mixer, I... but I start playing with them, so I say let’s play, no, no” (M1, FG2). | ||

| Overprotection | “...I’ve got this kid too groggy this boy should know how to walk on his own, he could even go to school on his own at the age of eight [...] however, because you have them so overprotected, it’s always ’I’ll take you, I’ll do it, I’ll...’, in the end they don’t know how to do anything on their own or how to go anywhere on their own” (M5, GF4). | ||

| Use of the car | “...we’ve got used to it, and it would take five minutes to walk from my house to here. But I bring my car with me because I have to go to work afterwards, so I don’t want to waste another five minutes to go home and take the car. So I come with the car and the children and that way I can go straight away” (F1, FG7). | ||

| Sibling influence | Older siblings encourage sedentary activities | “They have too much, so they spend too much of their free time [doing sedentary activities], they have finished their school and extracurricular activities, and they prefer to be, even with their siblings or whoever, spending their time on all these technologies...” (M6, GF4). “He has an older brother and when he was one year old he already liked to sit with his brother and watch him play, at one year old, so... when he was two years old he already knew how to use it. It’s something he loves” (M5, FG4). | |

| Educational factors that limited physical activity | Factors related to teachers and instructors that hinder physical activity | Poor involvement of the teacher or instructor | “The other teacher is more like ’come on, do a round’ and they run around. I mean, it depends a lot on the teacher they have, it all depends, I mean, I think that he is the one who moves the class and leads it, and if he doesn’t get involved, the children won’t get involved, that’s clear” (M1, FG2). “...When a monitor, clearly has many more students and maybe he/she is not so dedicated, spending individual time with them, I mean, really, they are like I don’t want to go, I’m bored, I don’t do anything, the teacher doesn’t pay attention to me...” (M3, FG2). “...She gave up modern dance. She didn’t give it up because she didn’t like it, but because of the teacher, who didn’t motivate her” (M2, FG7). |

| Strict teachers | “...The teachers should be chosen by the children, because in many cases they are very strict, and the children go to class with fear, and it shouldn’t be like that...” (M3, FG5). “...My daughters go because they like it, and they don’t care if I yell at them, if I put them last, you know? They like it. But there are girls who maybe... They aren’t warm enough, and they don’t have any tact for them...” (M4, FG7). | ||

| Elements of the school’s built environment that hinder physical activity | Poorly maintained facilities | “...Well, apart from what she has said, to have facilities, I think in good conditions, because sometimes schools don’t have good facilities for them to practice sport” (M4, FG7). | |

| Scarcity of facilities | “There are only two playing fields, and they are for each day, for a different year [...] they can’t just arrive and say, today I’m bringing the ball, because it’s not their turn” (F6, FG3). | ||

| Organization of the facilities | “It’s just that here at the school they also have a timetable for the courts, they can play football or basketball on the day they have a court available” (F6, FG3). | ||

| Home and neighborhood factors that hamper physical activity | Living in a small house | “...The type of game they play at home, depending on the fact that we don’t have much space, is more sedentary than when they go outside... in my house we don’t have much space either, like to run a lot, because you get dizzy [laughs], not so much now they are not so big” (M1, FG2). | |

| Lack of a terrace, courtyard or garden at home | “...It has nothing to do with having a playground with a basketball hoop for example, that you have, I don’t know, from having a lot of space, to having a very small house, a child who has to have 19 shelves because the toys can’t even be on the floor, at hand...” (M4, FG2). | ||

| Lack of common areas in the neighborhood | “...if you have a villa in La Moraleja, with tennis fields, swimming pool, and everything, well, you see, that person is more likely to do sport than someone who lives in an 80-metre flat” (M1, FG5). | ||

| Living in the city center | “... if you live in the center, in a flat as in this case, then those children in winter are indoors or are at home with their parents” (M4, FG5). | ||

| Mesosystem | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Subcategories | Code | Parents’ Verbalizations |

| Lack of communication between the school and the family | Children do not tell their parents what they do in physical education class | I ask my daughter ’what did you do today in gymnastics?’ and ugh... they don’t tell me anything specific, I don’t know... I’m a bit lost with gymnastics at school, especially in young children. When I was young I used to wear a tracksuit three days a week or I don’t know what the days were but they never did gymnastics” (M1, FG3). | |

| Parents do not ask their children what they do in physical education | “Because I... I would ask him about the classes, ’What have you done in class?’, and he would say ’well look, we have learnt this or that’, but in physical education I have never asked him ’What have you done in physical education?’, he does say ’well today mum we have played tag or this’, because they are new things that they don’t... but they don’t... they don’t talk to me about anything else, I don’t know what they call the things they do” (M4, FG8). | ||

| Lack of knowledge regarding the activities they carry out at school | “Because neither... as you can’t see them, of course, you can’t know... and that is what... or if they have an indoor sports facility day, because of the weather, I don’t know what activities they have there in the indoor sports facility, I just don’t know” (F6, FG3). | ||

| Lack of family conciliation | Overscheduled children | Excess of homework | “...It’s that homework has enslaved them [...] they already have a working day, as young as they are, of many hours” (M4, FG1). “But I had to take them out of basketball, because they either went to basketball or they did their homework, or one thing or the other. They didn’t get to everything on time” (M4, FG5). |

| Excess of organized after school activities | “...Those who have music school, music school takes up five or six hours a week, so they have the music school. So I have two children at the language school and with that they are already overworked” (F5, FG6). “Because of course, right now there are five days with activities, there are days, every day there are two activities except Friday with one, and it’s impossible, but not because I don’t want to” (F1, FG7). | ||

| Lack of time for free play | “They have all the day taken, let’s say, and the little play they have is almost when they have to go to bed, at least my children” (F6, FG3). “I think that children outside of [...] between school, classes and everything, they don’t have time to enjoy themselves” (M4, FG5). | ||

| Overburdened parents | Excessive workload | “I try to compensate a bit for the time I can’t spend during the week [...] But during the week I can’t spend time with her for playing, I can’t spend time dedicated to her, for example” (M8, FG6). “Many of us work so of course, you try to go with enough time, because if I take the child in a rush, I have to turn around again, so we have the same rhythm, not all of us, but at least in my case, I go with just enough time from one thing to another, so I can’t allow myself to take time out and say I’m going to walk, because I need that time for something else, so it’s not like that. Some people use the car for convenience, that’s true, but for me, at least in my case, it’s because of my work” (M2, FG3). | |

| Caring for several children | “But of course, it is also based on the fact that I have a young one and then I have the other older one, so of course you have to distribute...” (M7, FG6). | ||

| Exosystem | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Subcategories | Code | Parents’ Verbalizations |

| Barriers in the community and in the physical and built environment that hamper physical activity | Adverse weather conditions | “...Well, we have it divided into two seasons, winter and summer. In winter it’s cold and we can’t go outside, so all the activity is concentrated inside the house” (M2, FG2). “When it rains or whatever, they go inside and play video games or whatever, or watch TV. And when you leave them, they spend all day playing video games, it’s like that...” (M1, FG4). | |

| Lack of spaces and infrastructures for physical activity | “...In a big city you want to practice hockey and you can practice it, you want to practice thousands of sports and you have to... maybe you have to move, because of course, you are not going to have it in your neighborhood. But here, many sports, you can’t even practice them because you don’t have the possibility to practice them, nor do you have sports facilities to do so” (F2, FG1). “And then there are no sports facilities either, because they are, let’s say, owned by the council, you have to be registered to go and play, even in the few parks, unless it’s a sports center where everyone can go and play, not here, here if you go to the football pitch you have to be registered, if you go to Judo you have to be registered, but a sports center where kids can go and play and there is no traffic at all, there is none of that. There, they have basketball courts, tennis courts, paddle courts, indoor football courts, but here, there is none of that” (F6, FG3). | ||

| Low offers of organized activities and sports, cost of organized activities and materials | “...Maybe you have to move, because, of course, you won’t have it in your neighborhood. But here, many sports, you can’t even practice them because you don’t have the possibility to practice them” (M1, FG1). | ||

| Cost of organized activities and materials | “What happens is that it’s more expensive and it got to a point where I said ’no’, because you have to pay for the belts, which cost a lot of money. What it costs... to go to karate, then the outfit, then the trips that you have to take to the competition... and I’m just saying no” (M2, FG8). | ||

| Limitations on the use of public and community spaces | Restrictions and prohibitions | “You can’t play ball because it’s a park. You can’t ride a bike because it’s a park, parks have always been made for children to play, not to be restricted, right? Or removing them... Both here in the village and in a city, I know what happens, don’t I? Instead of creating free zones or clean zones for them to play in, they limit them” (F6, FG4). | |

| Occupation of parks and other spaces by older children | “There are also older kids, younger kids get kicked out right away and all that…” (M6, FG4). | ||

| Long distances | Difficulty in attending organized activities | “...My girls wanted to go to gymnastics, which they do. But since it’s so long, it’s impossible. It takes them a long time to eat and they arrive at four o’clock, it’s impossible, I don’t have time” (M5, FG3). | |

| Promotion of car use | “...When they go to the swimming pool, they go by car because it’s a bit further away” (M1, FG1). | ||

| Difficulties going outside to play with friends and schoolmates in urban areas | “...The after-school activity you had was to go out to the little square next, or to the park next to play, alone with friends from the neighborhood, but there was that, there were friends from the neighborhood, but now there aren’t any. Because now many of the children who come to this school don’t live in this neighborhood...” (M1, FG1). | ||

| Perceived lack of safety | Heavy traffic | “I remember when I was little, of course it was a long time ago, but you would go out and spend the whole afternoon playing and there was no problem at all. Your mother would call you to come in for a snack and you would come in, now the kid, I live practically opposite the school and you have to take him almost up to the door, because of the traffic. Everyone goes very fast with cars up and down the street, it’s not that you don’t want him to go out, but if it’s a street, more or less a busy one, you just can’t relax” (P1, GF5). “The limitations are set by us, because even though I have a school and so on, I don’t feel safe... for the child to go out alone at the age of seven, I don’t feel safe, maybe I’m paranoid, but there is a lot of traffic and I don’t feel safe. So for the child to go out alone I don’t...” (M3, FG7). “You can’t be sure that, if you go home to get something and she’s out, you can’t, you can’t, because with the traffic alone it’s impossible to leave her alone at any time, because in any situation they arrive and it’s impossible, it’s impossible, to be aware, no, no” (F6, FG1). | |

| Fear of accidents and abductions | “To be happy like before, you have to go back a few, a few good years, when children could go alone to their grandmother, without fear of being stolen or stepped on, of being caught out there, just like leaving the door open, that anything can happen...” (M2, FG5). “...I don’t know what generates fear, but it is true that you are afraid that they are on the street for fear of being abducted or for fear of being run over by a car or for fear of a lot of things...” (M5, FG4). | ||

| Need for supervision | “I don’t leave them anywhere unsupervised, I don’t leave them anywhere unsupervised, maybe I don’t know... maybe there are people who think that at seven years old they are old enough make a life for themselves” (M2, FG7). | ||

| Factors in the academic curriculum that limit physical activity | Insufficient time allocated to physical education | “I think that the role of the school in the physical activity of the children is minimal, they do the minimum, that is, there are three hours of class, of gymnastics, but they do the minimum. They don’t teach them, they don’t teach them to play basketball, or to play any sport” (M1, FG3). | |

| Physical education is assigned less importance than other subjects | “...But of course, if the academic obligation doesn’t leave you time for that... well... the academic obligation is a priority, whether we like it or not, this is the system. As long as they don’t give more importance to physical education” (F1, FG7). | ||

| Physical education as a graded subject | “I think that, for example, the fact that physical education is graded can be an incentive for some children and a demotivating one for others” (F2, FG6). | ||

| Macrosystem | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Subcategories | Code | Parents’ Verbalizations |

| Factors in the sociocultural context that limit physical activity | Sociocultural conditioning | Behavior of other parents | “So I don’t understand how a parent who is of a certain age can start insulting 10 year olds, or the referee or the coach, or tell them how they are doing things, right or wrong, when they are just training, or playing football” (F2, FG1). |

| Gender stereotypes | “Certain sports are still boxed in certain sexes, my daughter plays football and some mothers when you say ’I’m not going to take N to football’, ’but she’s going to football and she’s so beautiful!’" (F2, FG6). | ||

| Lifestyle changes | “Yes, but now the activity has changed a lot, because as he says, it’s true that we used to walk everywhere, my father couldn’t take me, I didn’t have a car, and we went out shopping on foot and we went everywhere. And then we went out into the street a lot to play, because back then there wasn’t that traffic, but it’s not that there wasn’t fear, let’s see, the fear we have now is maybe because there are reasons, because more things happen now than back then” (F5, FG4). | ||

| Influence of the media on the use of technologies | “Well, it’s the same thing, they have so much technology, that if they are not on their mobile phones all day with WhatsApp, if they are not with the PSP, if they are not with the PlayStation... they don’t know how to do anything else. Not because they don’t know how to do anything else, they do, because you teach them, you tell them to do it, but they prefer to do that. Because what they’ve been taught, not by their parents, but by everyone, the state, TV and everything, because they show it to you on TV” (F7, FG4). | ||

| Individual Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Subcategories | Code | Parents’ Verbalizations |

| Individual facilitators that encourage physical activity | Play as a meaningful occupation | “...So they start to play, but we go very quickly. If they can go out in the street with a ball and run, they do it...” (M5, FG1). “They love any game, no matter what it is. Now because football is the most famous, the most, but he doesn’t mind playing...” (M4, FG1). | |

| Young children are very active | “...He can’t sit still, he’s a very restless child and he can’t, he can’t, I’m sitting still here” (M3, FG2). “He is very active and spends all day playing” (F2, FG6). | ||

| Schoolchildren’s preferences | Preference for after school activities linked to physical activity | “Practicing any type of activity, anything that involves moving, seems very appropriate for him. So football, swimming... whatever, anything that involves movement” (M3, FG7). “Well, he prefers Movi-Kids to English, he prefers it” (M4, GFG8). | |

| Preference for active free play | “...In my house she dances from the moment she gets up to the moment she goes to bed, it’s incredible, what she likes, so of course, in my house she’s there all day long too. And then if we go to the park for a while in the afternoon, there are days when she takes her skates or her bicycle down...” (M4, FG7). | ||

| Preference for going outdoors to play | “He always wants to go out, well, if it were up to him, we’d be there all afternoon from six o’clock and he’s already saying “well, when are we going to go? When are we going to go?”, he likes it more... And then... I mean, if I don’t go out he goes out, it’s more about going downstairs than getting on the machine, he likes it more” (M1, FG4). | ||

| Microsystem | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Subcategories | Code | Parents’ Verbalizations |

| Family factors that promote physical activity | Parents as role models | “If they have never seen it at home or if you see your parents sitting there all day doing nothing, they follow the same... routine as their parents, maybe you can force them, but then I the future, if they see their parents who also go running and do sport and that, they also get used to seeing it in your own home, and it’s also good” (M3, FG5). | |

| Partnerships in activities | Family activities | “I have participated in mountain bike competitions and now I try to get my daughter to go out with me on the bike” (F8, FG6). “...Specifically, I do races, my girls come with me, the atmosphere of the day before, then the race, they get to know people, they get to know other children whose parents also race” (F6, FG6). “We do physical activity every day, we ride bicycles, we try... we also ride horses and we like to go for a walk, to run in the parks” (F7, FG4). | |

| Weekend activities | “And then maybe on a Saturday or Sunday you take them to the sports city to play football or basketball or something like that” (M1, FG5). “And on the weekends we go out with him on the bike and also on skates or go for a walk in the countryside, we like to go out” (M3, FG5). | ||

| Fathers encourage physical activity and active play | “He does a lot of sports with his father, swimming, cycling, and I have noticed in him, in his conversations, that with his father he does activities, I mean with me he does activities where emotions are much more involved” (M4, FG2). | ||

| Support from parents | Respect for the choice of children | “I don’t care, I like all of them, but I always look for something that motivates them, and that they really enjoy and have a good time with [...] so for the moment, they are happy with basketball” (F2, FG1). “...I like them to do some sport, but, as they said, something that they like, that they enjoy doing it so that they don’t get tired and that it is not something imposed by the father or the mother” (M1, FG1). | |

| Promote children’s autonomy | “...I leave him some time to decide what he wants to do, if he wants to play, if he wants to watch a bit of television, a bit of tablet and then early, at half past nine or so, he is in bed” (M4, FG2). “The mothers listen to them first, and depending on what the children say and we see more or less what they want, that’s how we do it” (M2, FG8). | ||

| Value placed on physical activity by parents | Physical activity is important | “I also think it is important to practice sport, children are more active, with more energy” (M1, FG3). | |

| Physical health benefits | “I like my children to do sport because it is also good for them, it also takes away a bit of adrenaline, and I don’t know, it’s good for their health” (M3, FG5). “We are very aware of his weight, I always weigh him and tell him that he can’t get fat, that he has to move, that this is very good for him, for his health” (M4, FG4). | ||

| Psychological benefits | “The stress of after school activities, school, the continuous school day. Well, I think that sport, just as it helps us to disconnect, it helps them too” (M4, FG6). “You see, I think that sport is good for them, and not only for children, in general it is good for the brain” (M2, FG5). | ||

| Social benefits | “I also think that it is also very good for them, playing with other children, companionship, learning to share with other children, playing in new situations” (M3, FG5). “...Coordination and sports are more important, where they learn the values of companionship and so on. They are the ones they have to learn at that age” (F3, FG1). | ||

| Parents limit screen viewing time | “...Even if they are cartoons, that are didactic, or activities that are healthy for them, but... then with... well, a bit of everything, a bit of physical activity, not just watching TV or that, of tablets and new technologies, which is fine, but in the right measure” (M3, FG7). | ||

| Positive influence of friends | Choice of after school activities their friends do | “...If someone told him that he is going to join the football school, he will also want to join because he is his friend” (M1, FG5). | |

| Preferences for going out to play with friends | “If he’s alone, he usually plays a board game, or a game of Play Station or something like that. But if he is with other people, he’s not attracted to those games, he likes to play tag, or play with the ball or things like that” (M4, FG3). “These days when the weather is nice, he is eager to see the door open and see the girl in front of him to run out on the street” (M3, FG2). | ||

| Having siblings of similar ages stimulates play | “She is a very active girl and is always playing with her brother” (M1, FG3). | ||

| School factors promoting physical activity | Built environment of the school | Playground can encourage physical activity | “There is a large playground, there is a lot of... they should put, they could do more different activities at recess, invent new games for the children, I don’t know, things like that to motivate them not to sit down” (M2, FG3). |

| Existence of adequate spaces and materials | “The playground, yes, and the courts that are looked after and in good condition, so that the children can play. They should be provided with balls and things, but of course, that’s where they have physical education classes” (M3, FG8). | ||

| Teacher modelling | Involved and motivated teachers | “Recess, teachers who want to get involved, organize it a bit, so that they are not throwing stones at recess time, sitting on one side without knowing what to do, so they organize it a bit and they are delighted” (F2, FG6). | |

| Teachers who encourage movement in class | “He talks to them about the importance, my son tells me a lot about what V tells them, V talks to them about how important it is, he tells them ’he who moves his legs moves his heart!’ that’s why they are always moving their legs [laughs], it’s fundamental” (M4, FG2). | ||

| Household and neighborhood factors that encouraged physical activity | Large houses and single family dwellings | “If I have a big house, apart from the fact that I don’t put any limitations on them. If the little one wants to move the bike to the living room, I leave him with the bike in the living room. When they’re older, I’ll have it more organized. Then they play all over the house, they have a yard, they have a swimming pool and downstairs they also have a big place, so if they want to ride their bikes or whatever they want” (M1, GF3). | |

| Houses with terrace or garden | “I do have a big courtyard, where they can run, play and now in this weather they usually go outside. Yesterday they were outside all afternoon, but of course, they exercise” (M5, FG3). | ||

| Neighborhoods with common areas | “We live in a housing estate and as soon as the weather is good, they go out with their racquets, they go out with their balls and they spend an hour playing by themselves” (F3, FG1). “...It is also easier when the environment makes it easier for you, for example, now that we live in a housing estate, it is very easy. So they can go outside and run around, play..." (M5, FG1). | ||

| The street where they live allows them to go out to play | “I’m lucky to live on a street that is pedestrianized so you can go out and play there” (M4, FG3). | ||

| Mesosystem | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Subcategories | Code | Parents’ Verbalizations |

| Non-school periods and free time | Children are more active on holidays | “...But maybe in the summer they do more physical activity. They go with their grandparents to the beach and there they spend the whole day playing football, in the swimming pool, in the... whatever. Basketball, tennis” (F2, FG1). | |

| Children are more active during weekends | “Then at weekends in the village he has the bike, and there too, but at his own free will” (M4, FG1). “I mean, at weekends, of course you don’t have to follow the routine, because of course, the children have their school and you have to respect that, you have to... so if you follow it, but at weekends you have more freedom, I mean, we are going to get up early and go to this place, we are going to do this, they don’t have school, and of course the parents don’t have to work, you have more free time, so you can do a lot more activities with them” (M3, FG2). | ||

| The school as a setting that transmits values | School is important for promoting physical activity | “It is very important, but everyone, even the members of the child’s family, it is very important that the child is taught sport” (M4, FG2). “I think it is very important, I mean, what we are, what we said before, children, the younger they are, they are sponges, in terms of, in terms of learning languages, everything. So, if you, if they have a good sporting education when they are young, I don’t know what they are taught, psychomotor skills, all these things, you can teach a young child to swim and they will learn better than if you try to learn when they are older, because you have already picked up habits and changing those habits, at least for me it is more difficult to change them than learning from scratch” (M1, FG5). | |

| Exosystem | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Subcategories | Code | Parents’ Verbalizations |

| Community facilitators and the physical and built environment promoting physical activity | Good weather | “Every day of the month he swims in the summer, just when school finishes in June, and then he spends the whole summer, every day in the swimming pool, so summer is when he does sport seriously, every day, a lot” (M2, FG2). “In the summer, when it’s hot, they come home from school, they eat, they go out again, they come home, they cool down a bit, they eat again and go to the park” (M2, FG5). | |

| Factors in the public and community space that promote physical activity | Living in a rural area | “It’s different living in a city than living in a town, that’s for sure. Because in a city, well, first you go everywhere by car, with public transport, you don’t walk, unless you go... you do a separate activity. In the village you can walk anywhere, to school, to activities, to go shopping. So that’s something different from the city” (M4, FG7). | |

| Living in a small town | “...Well, in a city like Cuenca, which is small, where you can walk to many places, where you can see your schoolmates or friends because you meet them in the street, well, that also makes it much easier, to have that environment, what she said about living in Madrid, where they leave school, they have to take the metro, they have to take a bus, so the environment changes a lot, of course” (F1, FG1). “Then living in a, in a small town, where everything is close, I think that.... well, it’s positive in that, it’s not like in a city where you have to take the metro or take the train, bus and all that. I think that here you have everything next to home” (M1, FG5). | ||

| Wide range of activities and infrastructures in urban areas | “Living in a small city, as he said, also the sports facilities that you can find. You can’t have sports facilities for everything, like in a big city. In a big city, you want to practice water polo and here you know for example that you have a swimming pool, but it’s for swimming” (F1, FG1). | ||

| Existence of parks and gardens close to home | “So if you are lucky enough to live near a park or to be able to have one nearby, they go out on their own and run, of course” (M5, FG1). | ||

| Organization of after school activities related to sport and physical activity. | Involvement of the parents’ association in the organization of after school activities | “...They have n parents’ association that is very involved and all that, and here you can see that they are more relaxed” (M1, FG2). “Their role is to organize everything, both sports and after school activities, or... to organize everything, and they plan the whole year” (M4, FG5). | |

| Macrosystem | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Subcategories | Code | Parents’ verbalizations |

| Facilitators of the socio cultural and political context | Physical activity is in fashion | “I do think that fashion influences everything, just like fashion in clothes, fashion in sport, because before, nobody ran, and now everybody runs like fools, they run and run” (F1, FG7). | |

| Free or subsidized activities and venues | "Because the activities are free, for example. For example, the children here the activities are free, so they do the activities there, they come here to play whatever they do here” (M4, FG5). | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alcántara-Porcuna, V.; Sánchez-López, M.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Martínez-Andrés, M.; Ruiz-Hermosa, A.; Rodríguez-Martín, B. Parents’ Perceptions on Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity among Schoolchildren: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063086

Alcántara-Porcuna V, Sánchez-López M, Martínez-Vizcaíno V, Martínez-Andrés M, Ruiz-Hermosa A, Rodríguez-Martín B. Parents’ Perceptions on Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity among Schoolchildren: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(6):3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063086

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlcántara-Porcuna, Vanesa, Mairena Sánchez-López, Vicente Martínez-Vizcaíno, María Martínez-Andrés, Abel Ruiz-Hermosa, and Beatriz Rodríguez-Martín. 2021. "Parents’ Perceptions on Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity among Schoolchildren: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 6: 3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063086

APA StyleAlcántara-Porcuna, V., Sánchez-López, M., Martínez-Vizcaíno, V., Martínez-Andrés, M., Ruiz-Hermosa, A., & Rodríguez-Martín, B. (2021). Parents’ Perceptions on Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity among Schoolchildren: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063086