Implementing Anti-Racism Interventions in Healthcare Settings: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

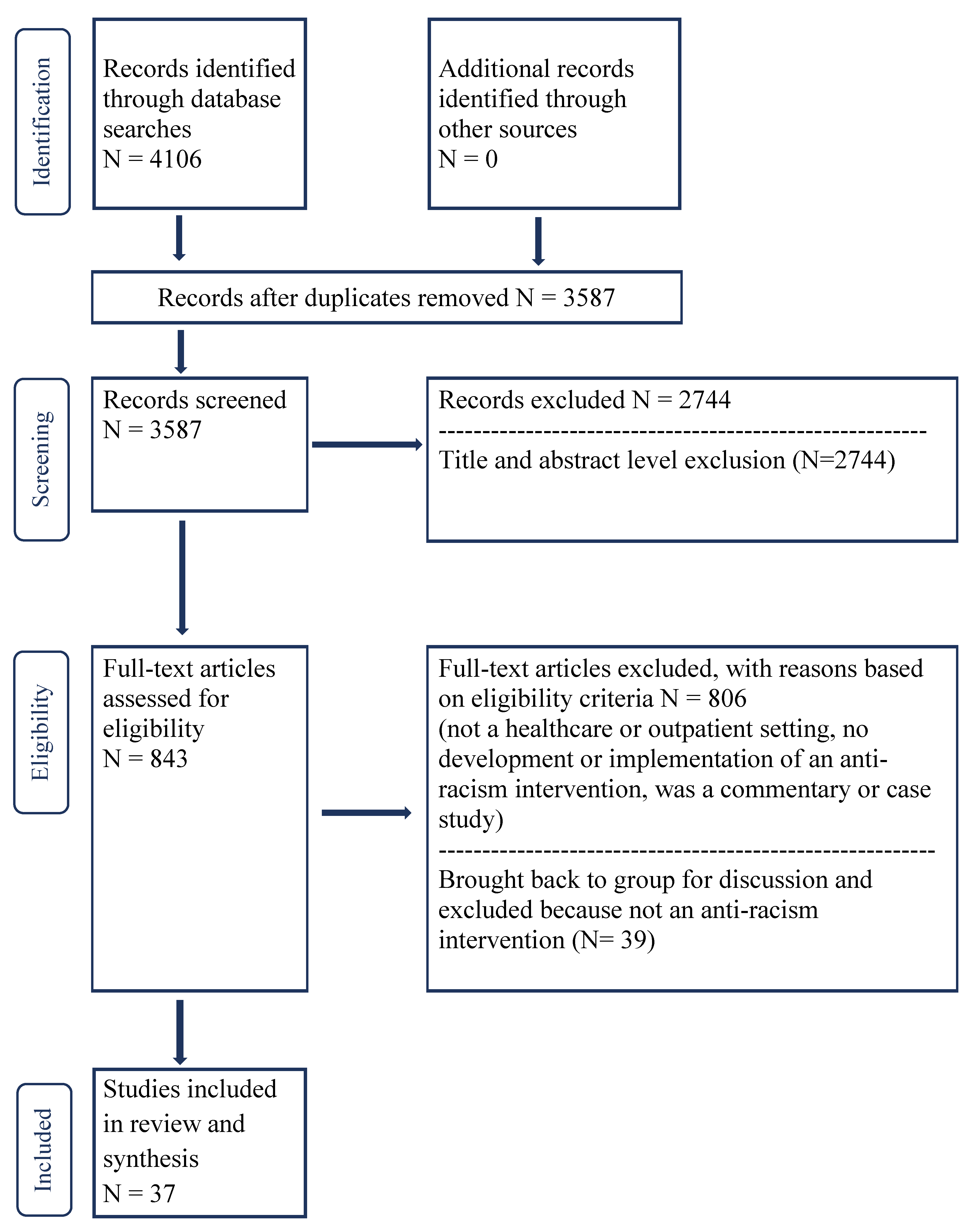

2. Methods

3. Working Definitions of Anti-Racism Intervention and Types of Racism

4. Results

4.1. Overview of the Literature

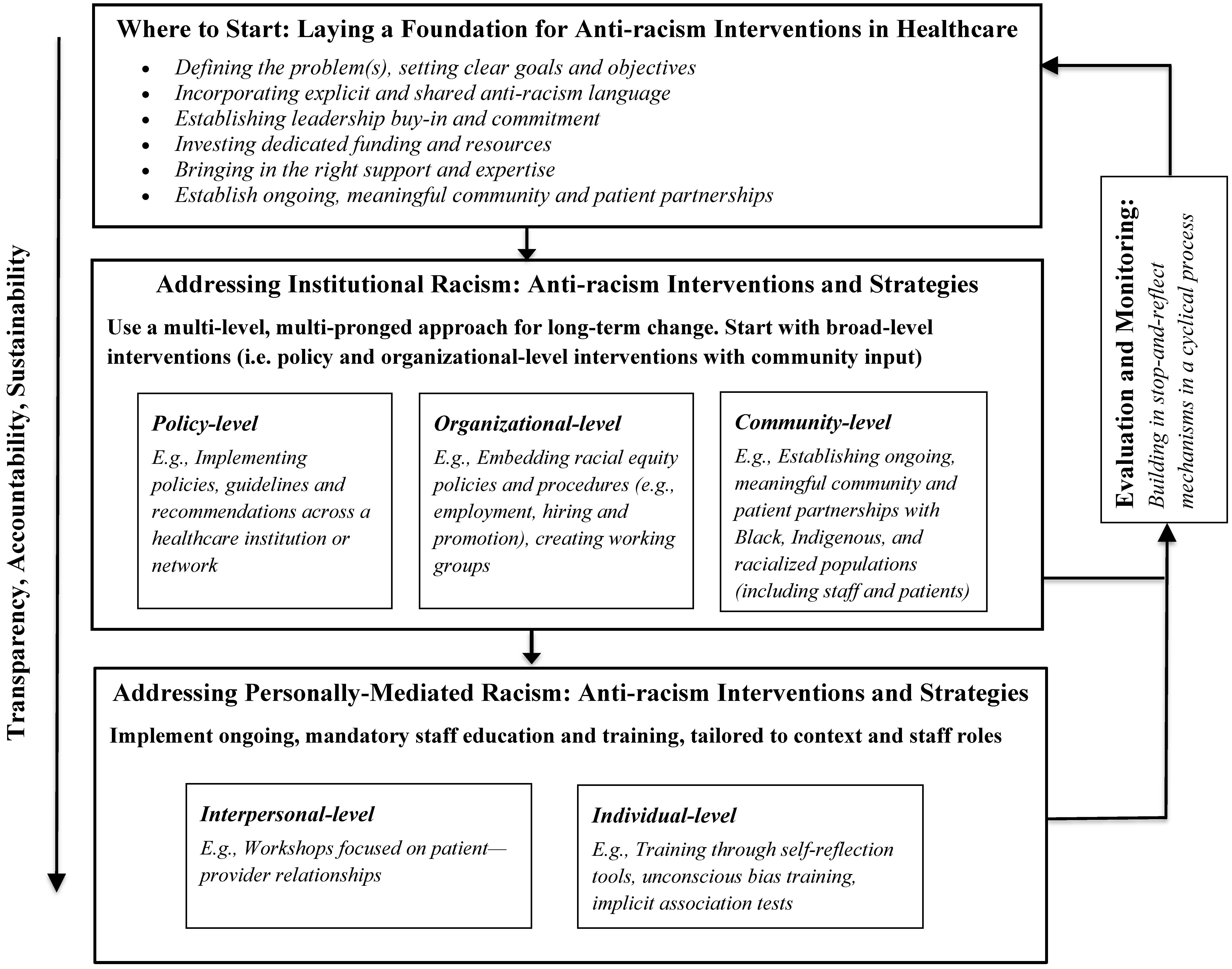

4.2. Foundational Principles for Anti-Racism Interventions in Healthcare Settings

4.3. Define the Problem(s) and Set Clear Goals and Objectives

4.4. Incorporate Explicit and Shared Anti-Racism Language

4.5. Establish Leadership Buy-In and Commitment

4.6. Invest Dedicated Funding and Resources

4.7. Bring in the Right Support and Expertise

4.8. Establish Ongoing, Meaningful Community and Patient Partnerships

5. Anti-Racism Strategies for Implementation and Evaluation

5.1. Use a Multi-Level, Long-Term Approach

5.2. Embed Racial Equity Policies and Procedures (e.g., Hiring, Retention and Promotion)

5.3. Link Mandatory Anti-Racism Work (Including Staff Education and Training) to Broader Systems of Power, Hierarchy and Dominance

5.4. Build in Stop-and-Reflect Mechanisms in a Cyclical Process

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Czyzewski, K. Colonialism as a Broader Social Determinant of Health. Iipj 2011, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGibbon, E.A. Anti-Racist Health Care Practice; Canadian Scholars’ Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009; 245p. [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby, C.D.E. Running Away from Drapetomania: Samuel A Cartwright, Medicine, and Race in the Antebellum South. J. South. Hist. 2018, 84, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, V.N. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. Am. J. Public Health 1997, 87, 1773–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, R. Governing Mentalities: The Deportation of Insane and Feebleminded Immigrants out of British Columbia from Confederation to World War II. Can. J. Law Soc. 1998, 13, 135–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosby, I. Administering Colonial Science: Nutrition Research and Human Biomedical Experimentation in Aboriginal Communities and Residential Schools, 1942–1952. Soc. Hist. 2013, 46, 145–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, K.M.; Trawalter, S.; Axt, J.R.; Oliver, M.N. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4296–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, K.H.; Deaton, C.; D’Adamo, A.P.; Goe, L. Ethnicity and analgesic practice. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2000, 35, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnorom, O.; Findlay, N.; Lee-Foon, N.K.; Jain, A.A.; Ziegler, C.P.; Scott, F.E.; Rodney,, P.; Lofters, A.K. Dying to Learn: A Scoping Review of Breast and Cervical Cancer Studies Focusing on Black Canadian Women. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2019, 30, 1331–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K.W. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. Univ. Chic. Leg. Forum 1989, 140, 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal, S.; Olfson, M.; Huang, C.; Pincus, H.; Gerhard, T. Broadened Use Of Atypical Antipsychotics: Safety, Effectiveness, And Policy Challenges. Health Aff. Chevy Chase 2009, 28, W770–W781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.M.; Mason, M.; Yonas, M.; Eng, E.; Jeffries, V.; Plihcik, S.; Parks, B. Dismantling institutional racism: Theory and action. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 39, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CADTH.ca. Grey Matters: A Practical Tool for Searching Health-Related Grey Literature. 2009. Available online: https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence/grey-matters (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Calliste, A.M.; Dei, G.J.S. Power, Knowledge and Anti-Racism Education: A Critical Reader; Fernwood: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2000; 188p. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.P. Levels of racism: A theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am. J. Public Health 2000, 90, 1212–1215. [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health (NCCDH). Let’s Talk: Racism and Health Equity. 2018. Available online: https://nccdh.ca/images/uploads/comments/Lets-Talk-Racism-and-Health-Equity-EN.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Module 1: Understanding the Social Ecological Model (SEM) and Communication for Development (C4D). 2014. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/earlychildhood/files/Module_1_-_MNCHN_C4D_Guide.docx (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Ring, J.M. Psychology and Medical Education: Collaborations for Culturally Responsive Care. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2009, 16, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signal, L.; Martin, J.; Reid, P.; Carroll, C.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Ormsby, V.K.; Richards, R.; Robson, B.; Wall, T. Tackling health inequalities: Moving theory to action. Int. J. Equity Health 2007, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, I.; Tilki, M.; Lees, S. Promoting cultural competence in healthcare through a research based intervention in the UK. Divers. Health Soc. Care 2004, 1, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Bekaert, S. Minority integration in rural healthcare provision: An example of good practice. Nurs. Stand. 2000, 14, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter New England Health Aboriginal and, Torres Strait Islander Strategic Leadership, Committee. Closing the gap in a regional health service in NSW: A multistrategic approach to addressing individual and institutional racism. NSW Public Health Bull. 2012, 23, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids). Cultural Competence Education Initiative. 2013. Available online: https://www.sickkids.ca/tclhinculturalcompetence/index.html (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. Policy Statement: Racism. 2002. Available online: https://rnao.ca/policy/position-statements/racism (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Public Health England. Local action on health inequalities—Understanding and reducing ethnic inequalities in health. 2018. Available online: https://nccdh.ca/resources/entry/local-action-on-health-inequalities-understanding-and-reducing-ethnic-inequ (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health. Key Public Health Resources for Anti-Racism Action: A Curated List. 2018. Available online: https://nccdh.ca/resources/entry/key-public-health-resources-for-anti-racism-action-a-curated-list (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- North Western Health Board (NWHB). North Western Health Board Anti-Racist Code of Practice. 2018. Available online: https://www.lenus.ie/handle/10147/42667 (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Healthcare Improvement Scotland. Equality Impact Assessments (EQIA). 2009. Available online: http://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org/about_us/what_we_do/equality_and_diversity/eqia.aspx (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Steed, R. Attitudes and beliefs of occupational therapists participating in a cultural competency workshop: Attitudes and Beliefs of Occupational Therapists. Occup. Ther. Int. 2010, 17, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, C.; Skorcz, S. African American Infant Mortality and the Genesee County, MI REACH 2010 Initiative: An Evaluation of the Undoing Racism Workshop. Soc. Work Public Health 2012, 27, 567–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, G.C. Racism in Medicine: Planning for the Future. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2001, 93, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Holm, A.L.; Rowe Gorosh, M.; Brady, M.; White-Perkins, D. Recognizing Privilege and Bias: An Interactive Exercise to Expand Health Care Providers’ Personal Awareness. Acad. Med. 2017, 92, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, J.; Moskowitz, G.B. Non-conscious bias in medical decision making: What can be done to reduce it?: Non-conscious bias in medical decision making. Med. Educ. 2011, 45, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heron, S.L.; Lovell, E.O.; Wang, E.; Bowman, S.H. Promoting Diversity in Emergency Medicine: Summary Recommendations from the 2008 Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors (CORD) Academic Assembly Diversity Workgroup. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2009, 16, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoli, E.; Pyati, A. Addressing clients’ racism and racial prejudice in individual psychotherapy: Therapeutic considerations. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 2009, 46, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betancourt, J.R.; Maina, A.W. The Institute of Medicine Report “Unequal Treatment”: Implications for Academic Health Centers. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2004, 71, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Betancourt, J.R. Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care: What Is the Role of Academic Medicine? Acad. Med. 2006, 81, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, J. The Right to Equal Treatment: Ending Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2004, 27, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staton, L.J.; Estrada, C.; Panda, M.; Ortiz, D.; Roddy, D. A multimethod approach for cross-cultural training in an internal medicine residency program. Med. Educ. Online 2013, 18, 20352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiman, S. Discovering Cultural Aspects of Nurse-Patient Relationships. J. Cult. Divers. 2006, 13, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP Statement on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2008, 65, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servonsky, E.J.; Gibbons, M.E. Family Nursing: Assessment Strategies for Implementing Culturally Competent Care. J. Multicult. Nurs. Health 2005, 11, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Havens, B.E.; Yonas, M.A.; Mason, M.A.; Eng, E.; Farrar, V.D. Eliminating Inequities in Health Care: Understanding Perceptions and Participation in an Antiracism Initiative. Health Promot. Pract. 2011, 12, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridley, C.R.; Chih, D.W.; Olivera, R.J. Training in cultural schemas: An antidote to unintentional racism in clinical practice. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2000, 70, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malott, K.M.; Schaefle, S. Addressing Client’s Experiences of Racism: A Model for Clinical Practice. J. Couns. Dev. 2015, 93, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, A.J.; Varcoe, C.; Smye, V.; Reimer-Kirkham, S.; Lynam, M.J.; Wong, S. Cultural safety and the challenges of translating critically oriented knowledge in practice. Nurs. Philos. 2009, 10, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racher, F.E.; Annis, R.C. Respecting Culture and Honoring Diversity in Community Practice. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2007, 21, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, S. Beyond Self-Assessment- Assessing Organizational Cultural Responsiveness. J. Cult. Divers. 2008, 15, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, A.J.; Varcoe, C.; Lavoie, J.; Smye, V.; Wong, S.T.; Krause, M.; Tu, D.; Godwin, O.; Khan, K.; Fridkin, A. Enhancing health care equity with Indigenous populations: Evidence-based strategies from an ethnographic study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 544–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocke, C. The Use of Humor to Help Bridge Cultural Divides: An Exploration of a Workplace Cultural Awareness Workshop. Soc. Work Groups 2015, 38, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.; Keating, F. Training to redress racial disadvantage in mental health care: Race equality or cultural competence? Ethn. Inequalities HSC 2008, 1, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, N.; Esmail, A.; Kline, R.; Rao, M.; Coghill, Y.; Williams, D.R. Promoting equality for ethnic minority NHS staff—what works? BMJ 2015, 351, h3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, S.; Spangaro, J.; Lauw, M.; McNamara, L. The Intersection of Trauma, Racism, and Cultural Competence in Effective Work with Aboriginal People: Waiting for Trust. Aust. Soc. Work 2013, 66, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durey, A.; Wynaden, D.; Thompson, S.C.; Davidson, P.M.; Bessarab, D.; Katzenellenbogen, J.M. Owning solutions: A collaborative model to improve quality in hospital care for Aboriginal Australians. Nurs. Inq. 2012, 19, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durey, A.; Thompson, S.C.; Wood, M. Time to bring down the twin towers in poor Aboriginal hospital care: Addressing institutional racism and misunderstandings in communication. Intern. Med. J. 2011, 42, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnott, M.J.; Wittmann, B. An Introduction to Indigenous Health and Culture: The First Tier of the Three Tiered Plan. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2001, 9, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rix, E.; Barclay, L.; Wilson, S. Can a white nurse get it? ‘Reflexive practice’ and the non-Indigenous clinician/researcher working with Aboriginal people. Rural Remote Health 2014, 14, 2679–2692. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, P.; Centre, H.R.B.; Puhiawe, N.; Horotakere, N.; Wilson, D. Te Kapunga Putohe (The Restless Hands): A Maori Centred Nursing Practice Model. Nurs. Prax. New Zealand 2008, 24, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D. The nurse’s role in improving indigenous health. Contemp. Nurse 2003, 15, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, A.S.; Hardy, B.-J.; Firestone, M.; Lofters, A.; Morton-Ninomiya, M.E. Vagueness, power and public health: Use of ‘vulnerable‘ in public health literature. Crit. Public Health 2019, 30, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonham, A.C.; Solomon, M.Z. Moving Comparative Effectiveness Research Into Practice: Implementation Science And The Role Of Academic Medicine. Health Aff. 2010, 29, 1901–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Informing the Plan • Racial Equity Tools. Available online: https://www.racialequitytools.org/plan/informing-the-plan/organizational-assessment-tools-and-resources (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Benjamin, R. Race for Cures: Rethinking the Racial Logics of ‘Trust’ in Biomedicine. Sociol. Compass 2014, 8, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, R.; Stefancic, J. Critical Race Theory (Third Edition): An Introduction; University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, E. Seven things organisations should be doing to combat racism. Lancet 2020, 396, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Number of Articles (%) |

|---|---|

| United States of America [12,19,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46] | 19 (51%) |

| Canada [47,48,49,50,51] | 5 (14%) |

| United Kingdom [21,22,52,53] | 4 (11%) |

| Australia [23,54,55,56,57,58] | 6 (16%) |

| New Zealand [20,59,60] | 3 (8%) |

| Target Healthcare Provider Group | |

| Nurses [41,43,47,48,55,58,59,60] | 8 (22%) |

| Physicians [19,32,34,35,38,40,56,57] | 8 (22%) |

| Psychologists/Counsellors [21,36,45,46,52] | 5 (11%) |

| Social Workers [54] | 1 (3%) |

| Occupational Therapists [30] | 1 (3%) |

| Pharmacists [42] | 1 (3%) |

| Other/Not specified | 13 (35%) |

| Target Patient Group | |

| Indigenous populations as a patient group (includes Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, Maori, First Nations, Inuit, and Metis/Native Americans) [20,23,26,47,50,51,54,55,56,57,58,59,60] | 12 (32%) |

| Black populations as a patient group (includes Black and African American) [30,31,32,52,53] | 5 (14%) |

| Other minority and racialized patient groups using terms like “minority groups”, “clients of colour”, “non-White”, “racial and ethnic minorities” | 12 (32%) |

| Healthcare Setting | |

| Hospitals (outpatients) [22,35,37,47,51,55,56] | 8 (21%) |

| Network or regional level with direct patient reach [12,20,23,33,39,42,44] | 7(19%) |

| Primary care [21,43,46,50,58,60] | 6 (14%) |

| Community-based settings providing outpatient care [19,30,31,48,52,54] | 6(14%) |

| Level of Intervention | |

| Individual [19,21,22,30,34,37,38,40,41,42,47,50,54,55,56,58,59] | 20 (54%) |

| Interpersonal [20,23,30,33,36,37,38,41,43,44,45,47,50,51,52,54,56,58,59] | 19 (51%) |

| Community [12,23,48,50,55,56,59,60] | 8 (21%) |

| Organizational [12,22,31,32,35,37,38,39,42,44,47,48,49,51,52,53,54,55,56,57] | 21 (57%) |

| Policy [12,20,23,32,35,37,38,42,53] | 9 (24%) |

| Individual-level: 20 articles (54%) |

|

| Interpersonal-level: 19 articles (51%) | |

| Community-level: 8 articles (21%) |

|

| Organizational-level: 21 articles (57%) |

|

| Policy-level: 9 articles (24%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hassen, N.; Lofters, A.; Michael, S.; Mall, A.; Pinto, A.D.; Rackal, J. Implementing Anti-Racism Interventions in Healthcare Settings: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2993. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062993

Hassen N, Lofters A, Michael S, Mall A, Pinto AD, Rackal J. Implementing Anti-Racism Interventions in Healthcare Settings: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(6):2993. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062993

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassen, Nadha, Aisha Lofters, Sinit Michael, Amita Mall, Andrew D. Pinto, and Julia Rackal. 2021. "Implementing Anti-Racism Interventions in Healthcare Settings: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 6: 2993. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062993

APA StyleHassen, N., Lofters, A., Michael, S., Mall, A., Pinto, A. D., & Rackal, J. (2021). Implementing Anti-Racism Interventions in Healthcare Settings: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 2993. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062993