Experiences of Being a Couple and Working in Shifts in the Mining Industry: Advances and Continuities

Abstract

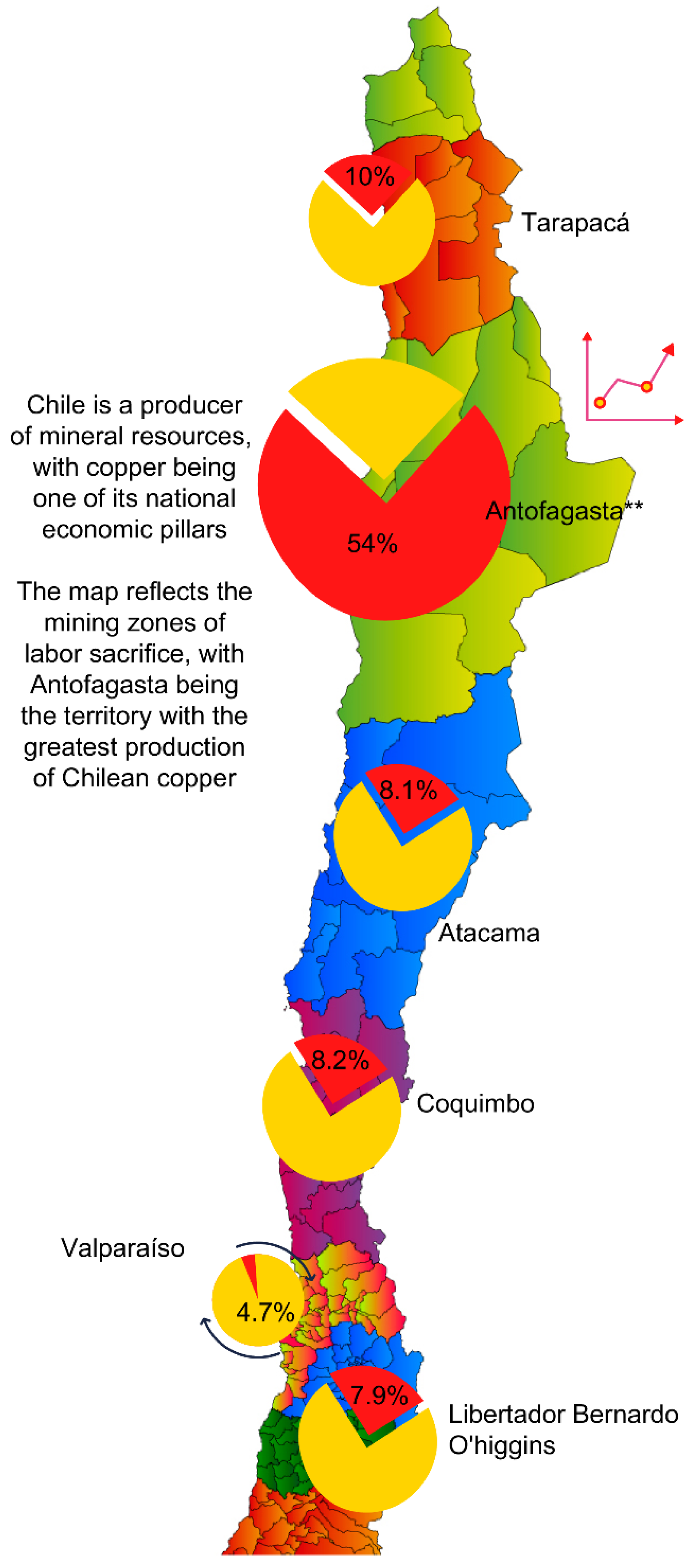

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Regarding the Information Production Strategy: The Interviews

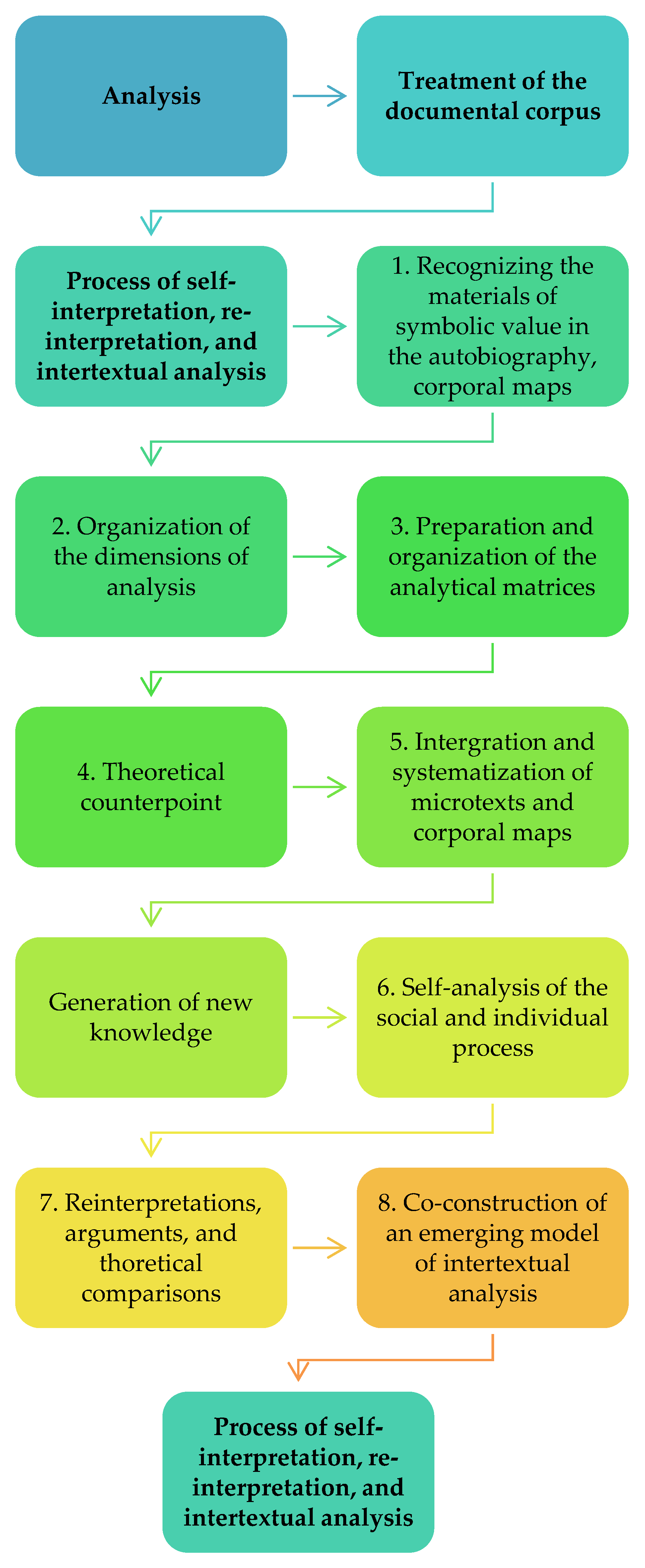

2.2. Regarding the Analysis Strategy: The Option for Critical Analysis of the Discourse

2.3. Participants

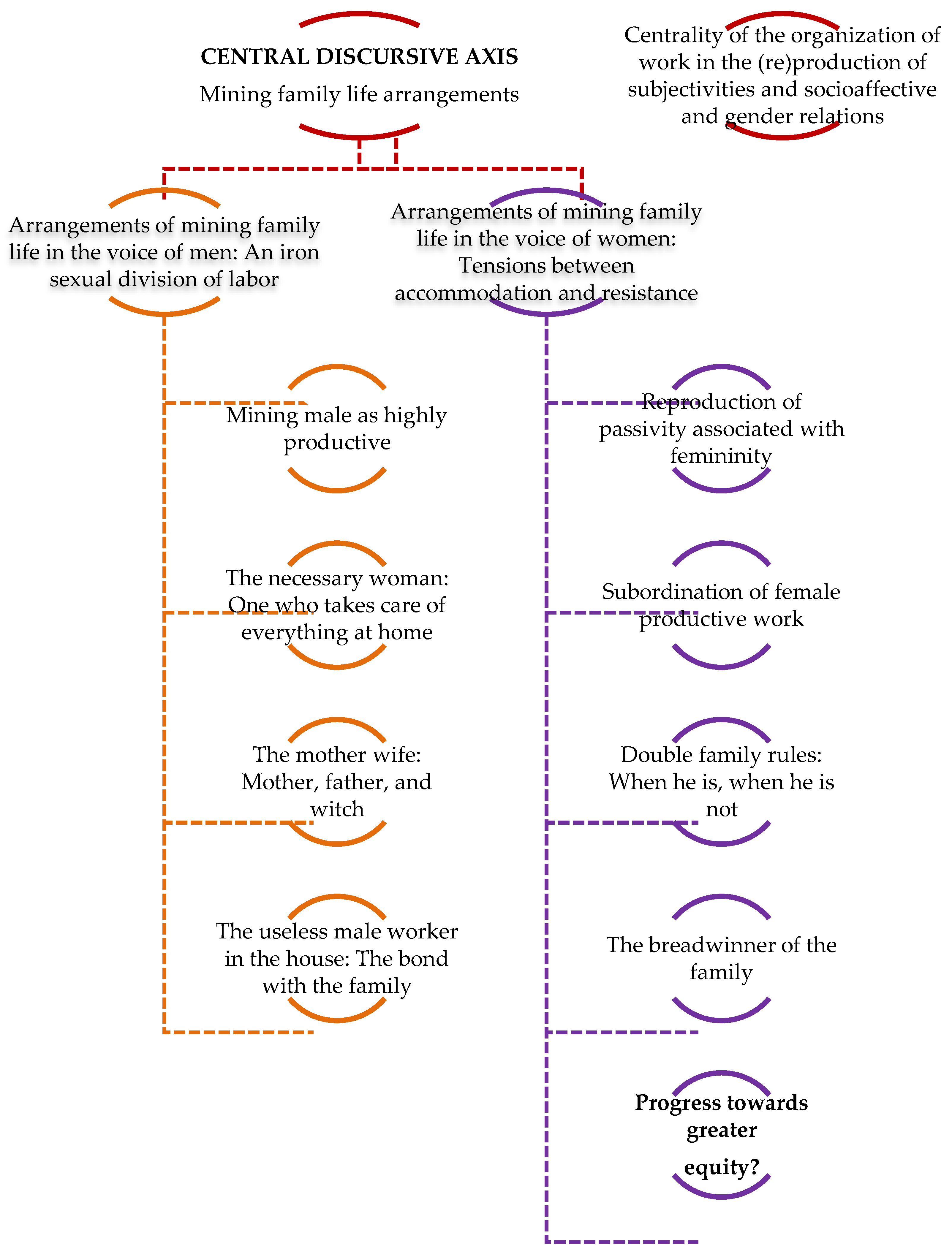

3. Discussion of the Results

3.1. Arrangements of Mining Family Life in the Voice of the Men: A Strictly Sexual Division of the Work

- The male miner as highly productive.

“You endure it. It’s impossible for a man to solve family matters, but on the job, a mining worker is highly productive! That is, the productivity of a mining worker is very high. We know that data. The men solve problems quickly; it’s technical, you look for ideas, you resolve, investigate. But they are not able to implement those abilities at home.”(José, 61 years old, three children)

- 2.

- The necessary woman: one who takes charge of everything at home.

“The women, in our case, have to take care of everything when we leave. You can’t be going down all the time, asking your boss for permission. You can’t go down, because if you are going to be going down, there are, I don’t know, fifteen of us up there and the boss is counting on the fifteen of us, so if you leave, the other fourteen feel it and have to take on the work of the one who left. So, the idea is to try not to go down, so you don’t look bad with the boss and also to take care of your job. For that reason, our women are important because they have to take care of everything.”(Mario, 32 years old, one child)

- 3.

- The mother spouse as mother, father and witch.

“The old lady has to know how to substitute at all times (accidents, birthdays, parties, others), when the children are sad the old lady has to deal with the little kids, so they don’t miss us, so while we are on the job, they don’t need anything from us.”(Pedro, 36 years old, two children)

“The other thing that happens to me is the matter of the kids. When I come home and they do something bad, I don’t scold them. I don’t feel I have the right to scold them because I am up on the site for seven days. If you come home and scold them, you end up being a bad father figure. So, I leave all that to my wife. My wife does their homework, teaches the children. Everything that has to do with the kids at home, I completely exempt myself (…) They end up being the witches, ha ha ha.”(Manuel, 40 years old, three children)

- 4.

- The male worker who is useless at home: money as a link to the family.

“After the shift, you come home to a house that your wife dominates. Your children don’t pay much attention to you. If it is you that tries to impose something, in the end, the only thing they want is for you to go back up to the mine. You become a provider, a provider and nothing, nothing else.”(Claudio, 38 years old, three children)

“I come back and the youngest pretends she doesn’t know me.”(Patricio, 42 years old, two children)

3.2. Arrangements of Mining Family Life in the Voice of the Women: Tensions between Accommodation and Resistance

- 5.

- Reproduction of passiveness associated with females.

“When he is at home, we don’t get bored because we say, “What are we going to do today?” “Let´s go for a walk,” we have to buy something. I don´t like to go downtown by myself unless I have to do an errand, and I don´t like to be in a line but I have to, and I do it with my head down. I don’t like to go window shopping either or have a coffee. If I have to visit my sister, my friend, or sister-in-law, I dare to go. He takes me everywhere. If I say, “I don´t want to cook,” he tells me, “Let’s eat out.”(Mónica, 43 years old, two children)

- 6.

- Subordination of female productive work.

“Since last year, I own a SME (small-to-medium enterprise) related to pastry. At the beginning, it was difficult because I was taking his time (from him when he was at home). I noticed, along with a group of girls, that when they come down from the mine, you have to be completely available for them because they have been confined. That’s what they think. When they come down, they like to go out. My husband likes spending time with his family. Last Friday, I had to deliver 400 sweets. I had told him that I wanted be at home early to start preparing my sweets in peace. He made us go out early, but I got back at 8 PM. I felt cheated because we did what he wanted to do anyway. So, it’s here where you have to give in a lot, so you don’t quarrel.”(Silvia, 35 years old, three children)

- 7.

- Dual family rules: when he is at home and when he is not.

“When he (husband) is at home, everything changes. For instance […], he doesn´t eat vegetables so I have to cook pasta. When my son and I are alone, I cook other types of meals. […] I don’t make plans when he´s at home. A woman comes to the house to iron when he is not at home because he doesn´t like strangers at home. When he is not at home, I make the rules, but when he arrives home, everything changes. For instance, I don’t leave things on the dinner table, but he leaves his shoes anyplace, his bag at the door until he is leaving, and he just unpacks it that day. I used to unpack it for him and put the things away, but not anymore. It´s another rhythm when he´s here, it´s something different at home.”(Estela, 50 years old, three children)

- 8.

- The mother as the support for the family.

“I am the witch, and he (the husband) is the boy who plays with him (the son) all day. Even last year, Vicente (son) was called on (at school) to recognize the family: I am the mother, and he is the father and the brother. The other day I answered him (her partner) and told him, “Thanks to me he loves you, because since he was a baby, he didn’t catch you [didn’t take him into account].” The child must have felt that he rejected him, since he wasn’t affectionate. They weren’t like they are now, that they are more like partners, more united. If one doesn’t feel the love from the other person, he is indifferent. That’s the feeling in their relationship. Over time, I insisted so much with him on Vicente that now they get along better. Now Vicente is bigger; I taught him to play ball, with cars—it wasn’t him.”(María, 45 years old, one child)

- 9.

- Advances toward greater equality?

“We both worked 4 × 3, and I was practically in charge of taking care of things at home regarding the bills and tasks that take a little longer (…). Regarding the house, we both took care of day-to-day or domestic things equally. And now that he is 4 × 3 and I am in Antofagasta, we turned things around. He is in charge of tasks that take a little longer, which are done on Fridays, and I am in charge of the house and the more urgent things that have to be done in Antofagasta (…). He generally makes the investment decisions or I consult with him so he knows, but that happens naturally. The same goes for family matters. I am the one in charge of the house, what to buy, what we need, what has to be put and what has to be taken out. It happens naturally (…) and we agree that way and get along well.”(Marcela, 32 years old, one son)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Observatorio Laboral Antofagasta (OLAB). Reporte Laboral Sectorial; Minería: Antofagasta, Chile, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas Chile (INE). Available online: https://www.ine.cl/prensa/2019/09/16/antofagasta-magallanes-y-o-higgins-lideraron-el-crecimiento-econ%C3%B3mico-interanual-en-el-primer-trimestre-de-2018 (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Ivanova, G.; Rolfe, J.; Williams, G. Assessing development options in mining communities using stated preference techniques. Resour. Policy 2011, 36, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, N.; Aroca, P. Escalas de Producción en Economías Mineras: El caso de Chile en su Dimensión Regional. Observatorio Regional de Desarrollo Humano. La Encuesta CASEN 2015: Algunos Resultados de Interés Para la Región de Antofagasta. EURE Santiago 2014, 40, 247–270. Available online: https://ordhum.com/2017/04/08/la-encuesta-casen-2015-algunos-resultados-de-interes-para-la-region-de-antofagasta/ (accessed on 18 February 2021). [CrossRef]

- Silva-Segovia, J.; Salinas-Meruane, P. With the mine in the veins: Emotional adjustments in female partners of Chilean mining workers. Gender Place Cult. 2016, 23, 1677–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, G.; Pávez, J.; Rebolledo, L.; Valdés, X. Trabajos y Familias en el Neoliberalismo: Hombres y Mujeres en Faenas de la UVA, el Salmón y el Cobre; LOM Ediciones: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Urrutia, V.G.; Figueroa, A.J. Corresponsabilidad familiar y el equilibrio trabajo-familia: Medios para mejorar la equidad de género. Polis Santiago 2015, 14, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelcos, N.; Pérez, M. De la “Desaparición” a la reemergencia: Continuidades y rupturas del movimiento de pobladores en Chile. Latin Am. Res. Rev. 2017, 52, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, S.; Grande, M.L. Participación política y liderazgo de género: Las presidentas latinoamericanas. América Latina Hoy. 2015, 71, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, P.; Román, H.; Armijo, L. Cuerpos de mujeres, significados de género y límites simbólicos en la gran minería en Chile. Polis 2020, 19, 186–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Barrientos, J. Guiones sexuales de la seducción, el erotismo y los encuentros sexuales en el norte de Chile. Rev. Estud. Fem. 2008, 16, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pini, B.; Mayes, R. Gender, emotions and fly-in fly-out work. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2012, 47, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winn, P.; Klubock, T.M. Contested communities: Class, gender, and politics in Chile’s El Teniente copper mine, 1904–1951. Am. Hist. Rev. 1999, 104, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, P.; Reyes, C.; Romani, G.; Ziede, M. Mercado laboral femenino. Un estudio empírico, desde la perspectiva de la de-manda, en la región minera de Antofagasta. Innovar 2010, 20, 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Segovia, J.; Lay-Lisboa, S. The power of money in gender relations from a Chilean mining culture. Affilia 2017, 32, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montecino, S.; Rebolledo, L.; Sunkel, G. Análisis del Impacto Psicosocial de los Sistemas de Trabajo por Turnos en la Unidad Familiar; SERNAM/Universidad de Chile: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pini, B.; Mayes, R.; Boyer, K. “Scary” heterosexualities in a rural Australian mining town. J. Rural. Stud. 2013, 32, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, P. Researching female sex work: Reflections on geographical exclusion, critical methodologies and ’useful’ knowledge. Area 1999, 31, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, P.; Sanders, T. Making space for sex work: Female street prostitution and the production of urban space. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, P. Revenge and injustice in the neoliberal city: Uncovering masculinist agendas. Antipode 2004, 36, 665–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, C.; Vega, P. Cuaderno de Investigación N° 40: Una Aproximación a las Condiciones de Trabajo en la Gran Minería de Altura; Estudios y Publicaciones: Quito, Ecuador, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. La Dominación Masculina; Anagrama: Barcelona, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Olavarría, J. Globalización, Género y Masculinidades. Las Corporaciones Transnacionales y la Producción de Productores. En Masculinidades y Globalización: Trabajo Y Vida Privada, Familias Y Sexualidades; Olavarría, J., Ed.; Universidad Academia de Humanismo Cristiano: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2009; pp. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Palermo, H. La Producción de la Masculinidad en el Trabajo Petrolero; Editorial Biblos: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dejours, C. Trabajo Vivo. Tomo 1. Sexualidad y Trabajo; Topía Editorial: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor, P.Z. Reproducción de la dominación masculina en la subjetivación del trabajo. Un análisis de discurso de gerentes generales en el Chile anterior a la explosión social. In Tratado Latinoamericano de Antropología del Trabajo; Palermo, H., Capogrossi, M.L., Eds.; Ceil Conicet: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2020; pp. 1381–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Leiva, S.; Comelin, A. Conciliación entre la vida familiar y laboral: Evaluación del programa IGUALA en una empresa minera en la región de Tarapacá. Rev. Polis 2015, 14, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Connell, R.; Masserschmidt, J. Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gend. Soc. 2005, 19, 829–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, D. Hacerse Hombre. Concepciones Culturales Sobre Masculinidad; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zerán, F. Mayo Feminista. La Rebelión Contra el Patriarcado; LOM Ediciones: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, N. La insurgencia feminista de mayo 2018. In Mayo Feminista. La Rebelión Contra el Patriarcado; Zerán, F., Ed.; LOM Ediciones: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2018; pp. 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. Triangulation 2.0. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2012, 6, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canales, M. Escucha de la Escucha. Análisis e Interpretación en la Investigación Cualitativa; LOM Ediciones: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J. La Circulación del Poder Entre Mujeres Chilenas de dos Generaciones: Las Hijas y Las Madres; Editorial Académica Española: Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J. Cuerpos Emergentes: Modelo Metodológico Para el Trabajo Corporal Con Mujeres; RIL Editors: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- De Villers, G. La historia de vida como método clínico. Proposiciones 1999, 29, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Musitano, J.; Surghi, C. Dossier: La dimensión biográfica. LA Palabra 2020, 36, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, T. La multidisciplinariedad del análisis crítico del discurso: Un alegato a favor de la diversidad. In Métodos de Análisis Crítico del Discurso; Wodak, R., Meyer, M., Eds.; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Montero, A. El análisis francés del discurso y el abordaje de las voces ajenas: Interdiscurso, polifonía, heterogeneidad y topos. In Escucha de la Escucha. Análisis e Interpretación en la Investigación Cualitativa; Canales, M., Ed.; Lom-Facso: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2013; pp. 247–273. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, B.; Harré, R. Posicionamiento: La produccion discursiva de la identidad. Athenea Digital Revista de Pensamiento e Investigación Social 2007, 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, P.Z. Reproducción de la Dominación Masculina en la Subjetivación del Trabajo. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Chile, Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D. Ciencia, Cyborgs y Mujeres. La Reinvención de la Naturaleza; Ediciones Cátedra: Barcelona, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Abarca, H.; Sepúlveda, M. Barras bravas. Pasión guerrera. Territorio, masculinidad y violencia en el fútbol chileno. In Jóvenes Sin Tregua: Culturas y Políticas de la Violencia; Ferrándiz, F., Feixa, C., Eds.; Anthropo: Barcelona, Spain, 2005; pp. 145–170. [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde, M. Claves Feministas Para la Autoestima de las Mujeres; Horas y Horas: Barcelona, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Llombart, M.P.; Leache, P.A. The gender binarism as a social, corporal and subjective “dispositif” of power. Quad. Psicol. 2010, 12, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraisse, G. Los dos Gobiernos: La Familia y la Ciudad; Ediciones Cátedra: Barcelona, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pisano, M. El Triunfo de la Masculinidad; Surada Ediciones: Santiago, Chile, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Valcárcel, A. La Política de las Mujeres; Cátedra: Barcelona, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Illouz, E. Intimidades Congeladas. Las Emociones en el Capitalismo; Katz Editores: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Transformation of Intimacy. Sexuality, Love & Eroticism in Modern Societies; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. Sociología; Alianza: Barcelona, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde, M. El derecho humano de las mujeres a una vida libre de violencia. In Mujeres, Globalización y Derechos Humanos; Maquieira, V., Ed.; Cátedra: Barcelona, Spain, 2010; pp. 477–534. [Google Scholar]

- Meler, I. Género, trabajo y familia: Varones trabajando. Subj. Procesos Cogn. 2004, 5, 223–244. [Google Scholar]

- Dejours, C.; Gernett, I. Psicopatología del Trabajo; Miño & Dávila: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Coria, C. El Sexo Oculto del Dinero. Formas de la Dependencia Femenina; Grupo Editorial Latino-Americano: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1986. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension: Referred to the Central Topic of Analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knots and conflicts | Subjects | Narrative | Subjective and gender experience tensions | Linked emotions | Search objects | Synthesis of interpretative analysis in the theoretical counterpoint |

| Identification of knots and their ramifications; coding of the interview; sex of the participant; age; microtexts and school assignment to selected text published extensively. | Coding of the interview; sex of the participant; age; attachment to school. | Microtexts and selected texts published extensively. | Analysis of the major emerging conflicts; microprints of the research objectives; articulated analysis of the theoretical core of the research. | Sensations and feelings that emerge in the affective–emotional story of the subjects. | Subjective expressions of the participants from a situated position. | Analysis of the theoretical core of research; counterpoint three levels: The protagonist, the researcher, and the theoretical aspects. |

| Synthesis of the analysis of the dimension in three voices: interviewee theories, and researcher. | ||||||

| Code | Age | Occupation | Shift System | Socioeconomic Level | No. of Children | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | José | 61 | Operator—union | 4 × 3 | Medium–low | 3 |

| 2 | Pedro | 36 | Mining worker | 7 × 7 | Medium–low | 2 |

| 3 | Claudio | 38 | Mining worker | 7 × 7 | Medium–low | 3 |

| 4 | Patricio | 42 | Mining worker | 4 × 3 | Medium–low | 2 |

| 5 | Manuel | 40 | Operator—union | 4 × 3 | Medium–low | 3 |

| 6 | Mario | 32 | Mining worker | 4 × 3 | Medium–low | 1 |

| 7 | Mónica | 43 | Homemaker | - | Medium–low | 2 |

| 8 | Silvia | 35 | Small business owner | - | Medium–low | 3 |

| 9 | Estela | 50 | Homemaker | - | Medium–low | 3 |

| 10 | María | 45 | Homemaker | - | Medium–low | 1 |

| 11 | Marcela | 32 | Homemaker (worked in mining) | . | Medium–low | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Segovia, J.S.; Pastor, P.Z.; Ravanal, E.C.; Segovia-Chinga, T. Experiences of Being a Couple and Working in Shifts in the Mining Industry: Advances and Continuities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042027

Segovia JS, Pastor PZ, Ravanal EC, Segovia-Chinga T. Experiences of Being a Couple and Working in Shifts in the Mining Industry: Advances and Continuities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(4):2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042027

Chicago/Turabian StyleSegovia, Jimena Silva, Pablo Zuleta Pastor, Estefany Castillo Ravanal, and Tarut Segovia-Chinga. 2021. "Experiences of Being a Couple and Working in Shifts in the Mining Industry: Advances and Continuities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 4: 2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042027

APA StyleSegovia, J. S., Pastor, P. Z., Ravanal, E. C., & Segovia-Chinga, T. (2021). Experiences of Being a Couple and Working in Shifts in the Mining Industry: Advances and Continuities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042027