Daily Work-Family Conflict and Burnout to Explain the Leaving Intentions and Vitality Levels of Healthcare Workers: Interactive Effects Using an Experience-Sampling Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Variables and Instruments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

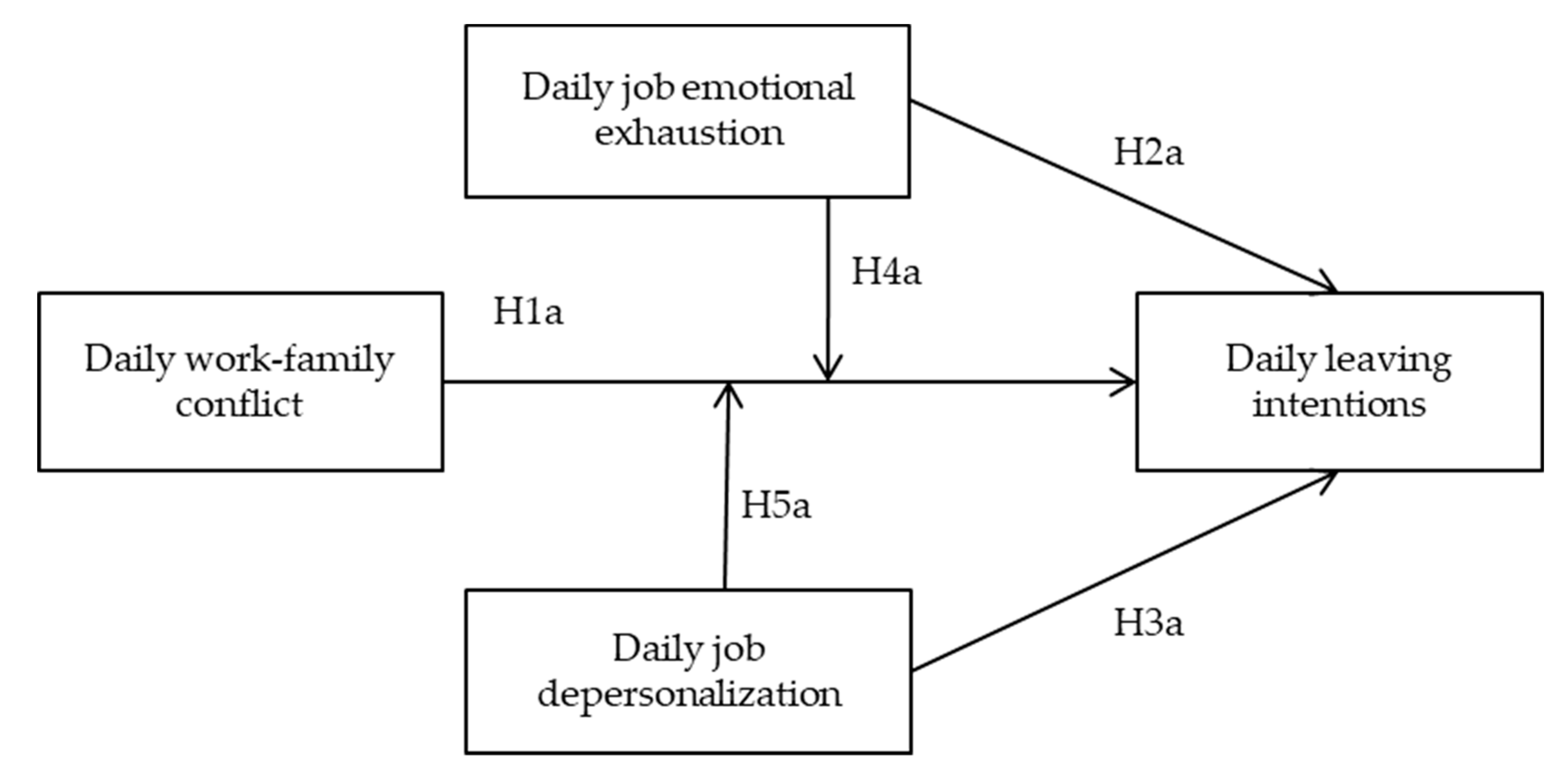

3.1. Hypothesis Testing

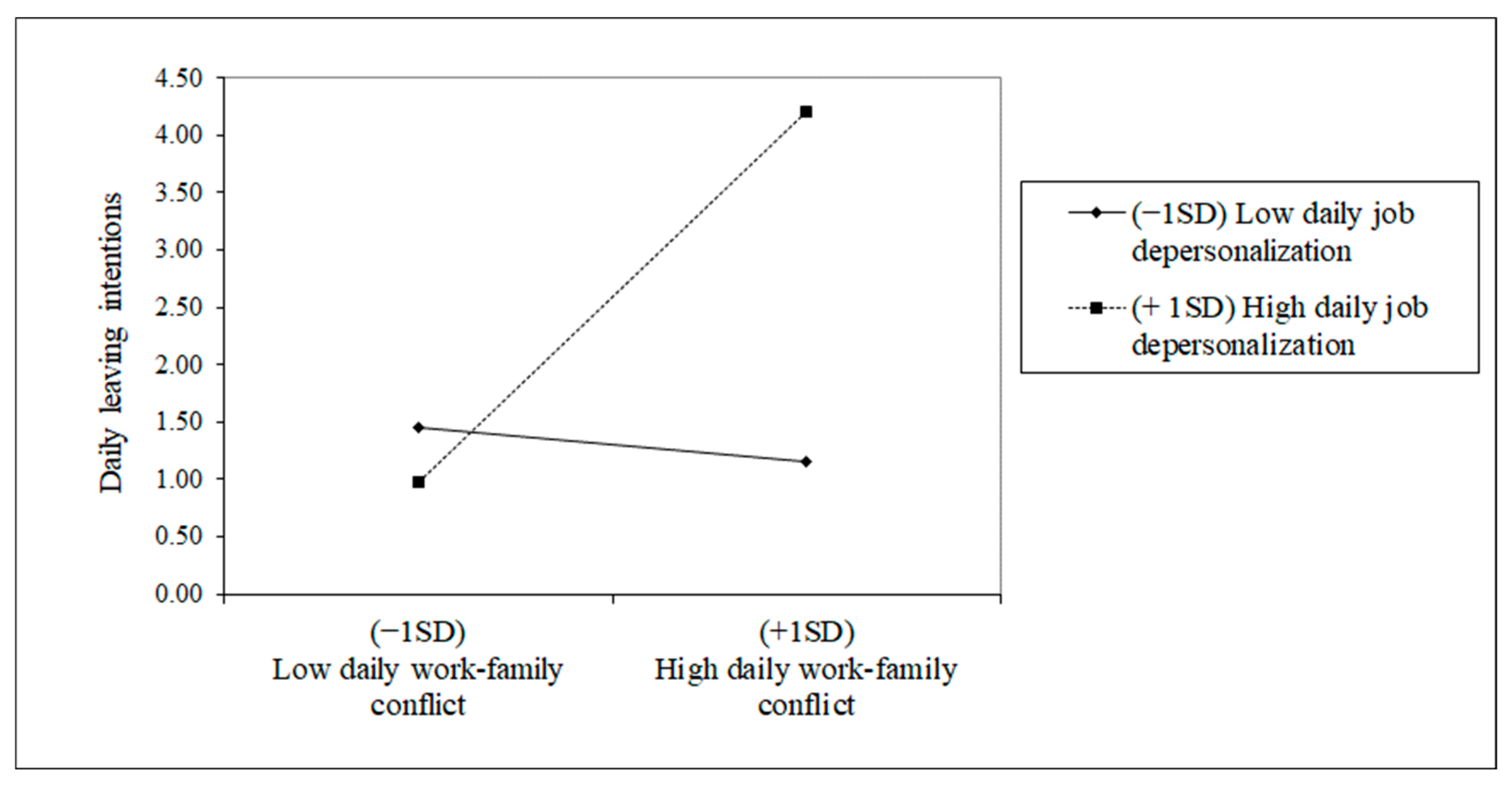

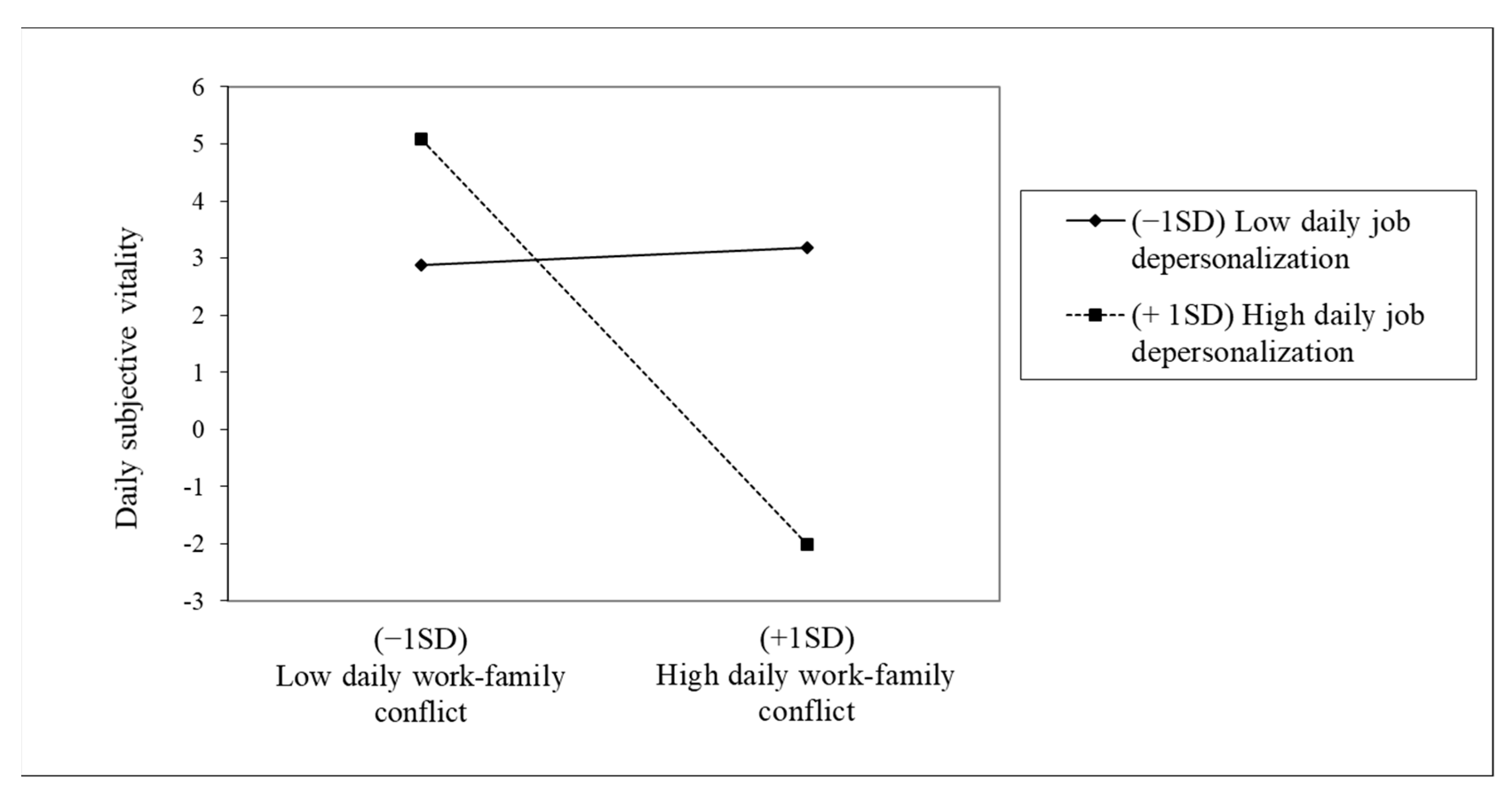

3.2. Interaction Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bouza, E.; Gil-Monte, P.; Palomo, E.; Cortell-Alcocer, M.; Del Rosario, G.; González, J.; Gracia, D.; Moreno, A.M.; Moreno, C.M.; García, J.M.; et al. Work-related burnout syndrome in physicians in Spain. Rev. Clínica Española 2020, 220, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messenger, J.; Vargas, O.; Gschwind, L.; Boehmer, S.; Vermeylen, G.; Wilkens, M. Working Anytime, Anywhere: The Effects on the World of Work; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. Managing Work-Related Psychosocial Risks during the COVID-19 Pandemic; Labour Administration, Labour Inspection and Occupational Safety and Health Branch: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 6–35. [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi, J.; Jackson, D.; Usher, K. The potential for COVID-19 to contribute to compassion fatigue in critical care nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2762–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoulay, E.; De Waele, J.; Ferrer, R.; Staudinger, T.; Borkowska, M.; Povoa, P.; Iliopoulou, K.; Artigas, A.; Schaller, S.J.; Hari, M.S.; et al. Symptoms of burnout in intensive care unit specialists facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Ann. Intensive Care 2020, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uvais, N.A.; Aziz, F.; Hafeeq, B. COVID-19-related stigma and perceived stress among dialysis staff. J. Nephrol. 2020, 33, 1121–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donchin, Y.; Seagull, F.J. The hostile environment of the intensive care unit. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2002, 8, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esin, M.; Sezgin, D. Intensive care unit workforce: Occupational health and safety. In Intensive Care; Shaikh, N., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017; pp. 199–224. [Google Scholar]

- McVicar, A. Workplace stress in nursing: A literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 44, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C.; Chiang, Y.-H.; Huang, Y.-J. Exploring the psychological mechanisms linking work-related factors with work–family conflict and work–family facilitation among Taiwanese nurses. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 581–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.H.; Tseng, P.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Lin, K.H.; Chen, Y.Y. Burnout in the intensive care unit professionals: A systematic review. Medicine 2016, 95, e5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cricco-Lizza, R. The need to nurse the nurse: Emotional labor in neonatal intensive care. Qual. Health Res. 2014, 24, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portoghese, I.; Galletta, M.; Leiter, M.P.; Cocco, P.; D’Aloja, E.; Campagna, M. Fear of future violence at work and job burnout: A diary study on the role of psychological violence and job control. Burn. Res. 2017, 7, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J.; Lee, J.H.; Gillen, M.; Krause, N. Job stress and work-related musculoskeletal symptoms among intensive care unit nurses: A comparison between job demand-control and effort-reward imbalance models. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2014, 57, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevala, T.; Pavey, L.; Chelidoni, O.; Chang, N.-F.; Creagh-Brown, B.; Cox, A. Psychological rumination and recovery from work in intensive care professionals: Associations with stress, burnout, depression and health. J. Intensive Care 2017, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrogante, O.; Aparicio-Zaldivar, E. Burnout and health among critical care professionals: The mediational role of resili-ence. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2017, 42, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Clarke, S.P.; Sloane, D.M.; Sochalski, J.; Silber, J.H. Hospital Nurse Staffing and Patient Mortality, Nurse Burnout, and Job Dissatisfaction. JAMA 2002, 288, 1987–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poghosyan, L.; Clarke, S.P.; Finlayson, M.; Aiken, L.H. Nurse burnout and quality of care: Cross-national investigation in six countries. Res. Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Işsever, O.; Bektas, M. Effects of learned resourcefulness, work-life quality, and burnout on pediatric nurses’ intention to leave job. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinkman, M.; Leino-Kilpi, H.; Salanterä, S. Nurses’ intention to leave the profession: Integrative review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 1422–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030; Health Workforce Department: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Jourdain, G.; Chênevert, D. Job demands–resources, burnout and intention to leave the nursing profession: A questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C. Relationships between workload perception, burnout, and intent to leave among medical–surgical nurses. Int. J. Evid. Based Heal. 2020, 18, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bogaert, P.; Meulemans, H.; Clarke, S.; Vermeyen, K.; Van De Heyning, P. Hospital nurse practice environment, burnout, job outcomes and quality of care: Test of a structural equation model. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 2175–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krausz, M.; Koslowsky, M.; Shalom, N.; Elyakim, N. Predictors of intentions to leave the ward, the hospital, and the nursing profession: A longitudinal study. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, W.; Fieldes, J.; Jacobs, S. An Integrative Review of How Healthcare Organizations Can Support Hospital Nurses to Thrive at Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Asakura, K.; Asakura, T. The Impact of Changes in Professional Autonomy and Occupational Commitment on Nurses’ Intention to Leave: A Two-Wave Longitudinal Study in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Wei, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Xu, Z. The Influence of Mistreatment by Patients on Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention among Chinese Nurses: A Three-Wave Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; French, K.A.; Braun, M.T.; Fletcher, K. The passage of time in work-family research: Toward a more dynamic perspective. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Gordon, S.; Tang, C.-H. Momentary well-being matters: Daily fluctuations in hotel employees’ turnover intention. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hippel, C.; Kalokerinos, E.K.; Haanterä, K.; Zacher, H. Age-based stereotype threat and work outcomes: Stress ap-praisals and rumination as mediators. Psychol. Aging 2019, 34, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Ora, C.; Griffiths, P.; Ball, J.; Simon, M.; Aiken, L.H. Association of 12 h shifts and nurses’ job satisfaction, burnout and intention to leave: Findings from a cross-sectional study of 12 European countries. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Jackson, D.; Stayt, L.; Walthall, H. Factors influencing nurses’ intentions to leave adult critical care settings. Nurs. Crit. Care 2019, 24, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, P.W.; Lee, T.W.; Shaw, J.D.; Hausknecht, J.P. One hundred years of employee turnover theory and research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstad, F.T.; Meier, L.L.; Fasel, U.; Elfering, A.; Semmer, N.K. A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyar, S.L.; Maertz, C.P., Jr.; Pearson, A.W.; Keough, S. Work-family conflict: A model of linkages between work and family domain variables and turnover intentions. J. Manag. Issues 2003, 15, 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, S.; Tremblay, D.-G. Work–family conflict/family–work conflict, job stress, burnout and intention to leave in the hotel industry in Quebec (Canada): Moderating role of need for family friendly practices as “resource passageways”. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 29, 2399–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Kümmerling, A.; Hasselhorn, H.-M. Work-Home Conflict in the European Nursing Profession. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Heal. 2004, 10, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Vergel, A.; Demerouti, E.; Gálvez, M. La conciliación vida laboral y familiar. In Salud Laboral. Riesgos Laborales Psico-Sociales y Bienestar Laboral; Moreno-Jiménez, B., Garrosa, E., Eds.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2013; pp. 407–424. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.; Allen, T.; Spector, P. Health Consequences of Work-Family Conflict: The Dark Side of the Work-Family Interface. In Employee Health, Coping and Methodologies; Perrewé, P., Ganster, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 5, pp. 61–99. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Parasuraman, S.; Collins, K.M. Career involvement and family involvement as moderators of relation-ships between work–family conflict and withdrawal from a profession. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job Burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boamah, S.A.; Laschinger, H.K.S. The influence of areas of worklife fit and work-life interference on burnout and turnover intentions among new graduate nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, E164–E174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañadas, G.A.; Albendín, L.; Cañadas, G.; San Luis, C.; Ortega, E.; De la Fuente, E.I. Nurse burnout in critical care units and emergency departments: Intensity and associated factors. Emergencias 2018, 30, 328–331. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, J.L.; De la Fuente, E.I.; Albendín, L.; Vargas, C.; Ortega, E.M.; Cañadas, G.A. Prevalence of burnout syndrome in emergency nurses: A meta-analysis. Crit. Care Nurse 2017, 37, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques-Pinto, A.; Élvio, H.J.; Cruz Mendes, A.M.O.; Fronteira, I.; Roberto, M.S. Nurses’ Intention to Leave the Organization: A Mediation Study of Professional Burnout and Engagement. Span. J. Psychol. 2018, 21, E32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tziner, A.; Rabenu, E.; Radomski, R.; Belkin, A. Work stress and turnover intentions among hospital physicians: The mediating role of burnout and work satisfaction. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2015, 31, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.I.; da Costa Ferreira, P.; Cooper, C.L.; Oliveira, D. How daily negative affect and emotional exhaustion cor-relates with work engagement and presenteeism-constrained productivity. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2019, 26, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrosa-Hernández, E.; Carmona-Cobo, I.; Ladstätter, F.; Blanco, L.M.; Cooper-Thomas, H.D. The relationships between family-work interaction, job-related exhaustion, detachment, and meaning in life: A day-level study of emotional well-being. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2013, 29, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Meier, L. Daily burnout experiences: Critical events and measurement challenges. In Burnout at Work: A Psychological Perspective, 1st ed.; Leiter, M., Bakker, A., Maslach, C., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 80–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, S.R.; Doering, M. An Integrated Model of Career Change. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1983, 8, 631–639. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, A.A.; Cropanzano, R. The Conservation of Resources Model Applied to Work–Family Conflict and Strain. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 54, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.T.; Ashforth, B.E. A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandey, A.; Cordeiro, B.; Crouter, A. A longitudinal and multi-source test of the work-family conflict and job satisfaction relationship. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2005, 78, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.C.; Ng, T.W.H. Careers: Mobility, Embeddedness, and Success. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 350–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, M.; Fouad, N.A. Why do women engineers leave the engineering profession? The roles of work-family conflict, occupational commitment, and perceived organizational support. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Frederick, C. On Energy, Personality, and Health: Subjective Vitality as a Dynamic Reflection of Well-Being. J. Pers. 1997, 65, 529–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, L.M.; Demerouti, E.; Garrosa, E.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Carmona, I. Positive benefits of caring on nurses’ motivation and well-being: A diary study about the role of emotional regulation abilities at work. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 804–816. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Sanz-Vergel, A.I. Weekly work engagement and flourishing: The role of hindrance and challenge job demands. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Inoue, T.; Harada, H.; Oike, M. Job control, work-family balance and nurses’ intention to leave their profession and organization: A comparative cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 64, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, J.; Dhar, R.L.; Tyagi, A. Stress as a mediator between work–family conflict and psychological health among the nursing staff: Moderating role of emotional intelligence. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2016, 30, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.T.; Williams, V.N.; Thorndyke, L.E.; Marsh, E.E.; Sonnino, R.E.; Block, S.M.; Viggiano, T.R. Restoring Faculty Vitality in Academic Medicine When Burnout Threatens. Acad. Med. 2018, 93, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, J.; Peeters, M.C. The Vital Worker: Towards Sustainable Performance at Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.D.; Ramos, J.D.; Ibáñez, O.; Cabrera, J.; Carmona, M.I.; Ortega, A.M. Compassion fatigue, burnout, compassion satisfaction and perceived stress in healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 health crisis in Spain. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 4321–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.-X.; Zhao, S.-Y.; Yuan, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.-F.; Gui, L.-L.; Zheng, H.; Zhou, Y.-M.; Qiu, L.-H.; Chen, J.-H.; et al. Prevalence and Influencing Factors on Fatigue of First-line Nurses Combating with COVID-19 in China: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. Curr. Med. Sci. 2020, 40, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Carvajal, R.; Herrero, M.; Van Dierendonck, D.; De Rivas, S.; Moreno-Jiménez, B. Servant Leadership and Goal Attainment Through Meaningful Life and Vitality: A Diary Study. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 20, 499–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanouli, A.; Hofmans, J. A Resource-based Perspective on Organizational Citizenship and Counterproductive Work Behavior: The Role of Vitality and Core Self-Evaluations. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubreuil, P.; Forest, J.; Courcy, F. From strengths use to work performance: The role of harmonious passion, subjective vitality, and concentration. J. Posit. Psychol. 2014, 9, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherbaum, C.A.; Ferreter, J.M. Estimating Stadistical Power and Required Sample Sizes for Organizational Research Using Multilevel Modeling. Organ. Res. Methods 2009, 12, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezlek, J. Multilevel Modeling Analyses of Diary-Style Data. In Handbook of Research Methods for Studying Daily Life, 1st ed.; Mehl, M., Conner, T., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 357–383. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Sanz, A.I.; Rodríguez, A.; Geurts, S.A. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Survey Work-Home Interaction Nijmegen (SWING). Psicothema 2009, 21, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Geurts, S.A.; Taris, T.W.; Kompier, M.A.; Dikkers, J.S.; Van Hooff, M.L.; Kinnunen, U.M. Work-home interaction from a work psychological perspective: Development and validation of a new questionnaire, the SWING. Work Stress 2005, 19, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno–Jiménez, B.; Garrosa, E.; González–Gutiérrez, J.L. Nursing burnout. Development and factorial validation of the CDPE. Arch. Prev. Riesg. Lab. 2000, 3, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Garrosa, E.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Liang, Y.; González, J.L. The relationship between socio-demographic variables, job stressors, burnout, and hardy personality in nurses: An exploratory study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Carvajal, R.; Díaz, D.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Blanco, A.; van Dierendonck, D. Vitality and inner resources as relevant components of psychological well-being. Psichothema 2010, 22, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton, C.; Rasbash, J.; Browne, W.J.; Healy, M.; Cameron, B. MLwiN Version 2.28; Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ohly, S.; Sonnentag, S.; Niessen, C.; Zapf, D. Diary studies in organizational research: An introduction and some practical recommendations. J. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 9, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouweneel, E.; Le Blanc, P.M.; Schaufeli, W.B.; van Wijhe, C.I. Good morning, good day: A diary study on positive emo-tions, hope, and work engagement. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1129–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Curran, P.J.; Bauer, D.J. Computational Tools for Probing Interactions in Multiple Linear Regression, Multilevel Modeling, and Latent Curve Analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2006, 31, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canivet, C.; Östergren, P.-O.; Lindeberg, S.I.; Choi, B.; Karasek, R.; Moghaddassi, M.; Isacsson, S.-O. Conflict between the work and family domains and exhaustion among vocationally active men and women. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. From Ego Depletion to Vitality: Theory and Findings Concerning the Facilitation of Energy Available to the Self. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2008, 2, 702–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Chen, L.; Chen, M.; Guan, X.; Wang, L.; Jiao, Y.; Yang, J.; Tang, Q.; Yang, X.; Qiu, X.; et al. Prevalence and factors associated with occupational burnout among HIV/AIDS heakthcare workers in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Muñoz, A.; Antino, M.; Ruiz-Zorrilla, P.; Sanz-Vergel, A.I.; Bakker, A.B. Short-term trajectories of workplace bullying and its impact on strain: A latent class growth modeling approach. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | M | SD | ICC | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. General leaving intentions | 1.90 | 0.83 | 0.91 | 1 | −0.23 ** | 0.12 | 0.39 ** | −0.09 | 0.50 ** | −0.13 | |

| 2. General subjective vitality | 4.53 | 1.10 | 0.87 | 1 | −0.36 ** | −0.48 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.33 ** | 0.52 ** | ||

| 3. Daily work-family conflict | 1.01 | 0.77 | 0.45 | 0.79 (0.73–0.84) | 1 | 0.37 ** | 0.15 * | 0.22 ** | −0.42 ** | ||

| 4. Daily job emotional exhaustion | 2.35 | 0.83 | 0.33 | 0.89 (0.88–0.90) | 1 | 0.16 ** | 0.49 ** | −0.36 ** | |||

| 5. Daily job depersonalization | 1.45 | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.85 (0.79–0.89) | 1 | 0.19 ** | −0.11 | ||||

| 6. Daily leaving intentions | 1.49 | 0.70 | 0.79 | 0.89 (0.86–0.92) | 1 | −0.20 ** | |||||

| 7. Daily subjective vitality | 2.98 | 1.09 | 0.39 | 0.83 (0.79–0.87) | 1 |

| Variables | Null Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | t | Estimate | SE | t | Estimate | SE | t | Estimate | SE | t | Estimate | SE | t | |

| Intercept | 1.490 | 0.085 | 17.529 *** | 1.500 | 0.069 | 21.73 *** | 1.500 | 0.069 | 21.73 *** | 1.500 | 0.069 | 21.73 *** | 1.499 | 0.068 | 22.044 *** |

| Sex | 0.013 | 0.011 | 1.181 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 1.181 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 1.181 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 1.181 | |||

| Age | 0.017 | 0.007 | 2.428 * | 0.017 | 0.007 | 2.428 * | 0.017 | 0.007 | 2.428 ** | 0.017 | 0.007 | 2.428 * | |||

| Time | 0.031 | 0.014 | 2.214 ** | 0.028 | 0.013 | 2.154 * | 0.026 | 0.013 | 2 * | 0.030 | 0.013 | 2.307 * | |||

| Shift | 0.071 | 0.053 | 1.339 | 0.071 | 0.053 | 1.339 | 0.072 | 0.053 | 1.358 | 0.069 | 0.052 | 1.327 | |||

| Profession | −0.039 | 0.143 | −0.272 | −0.040 | 0.143 | −0.279 | −0.038 | 0.143 | −0.265 | −0.031 | 0.142 | −0.218 | |||

| General leaving intention | 0.529 | 0.089 | 5.943 *** | 0.529 | 0.090 | 5.877 *** | 0.529 | 0.089 | 5.943 *** | 0.530 | 0.088 | 6.022 *** | |||

| Daily WF conflict | 0.196 | 0.039 | 5.025 *** | 0.157 | 0.041 | 3.829 *** | 0.169 | 0.042 | 4.024 ** | ||||||

| Daily job EE | 0.144 | 0.057 | 2.526 ** | 0.153 | 0.056 | 2.732 ** | |||||||||

| Daily job DEP | 0.086 | 0.059 | 1.458 | 0.124 | 0.061 | 2.033 * | |||||||||

| Daily Job EE X WF conflict | 0.028 | 0.104 | 0.269 | ||||||||||||

| Daily job D X WF conflict | 0.251 | 0.103 | 2.437 ** | ||||||||||||

| −2 X Log(lh) | 309.577 | 252.129 | 228.933 | 219.514 | 213.166 | ||||||||||

| Difference of −2 X Log | 57.448 *** | 23.196 *** | 9.419 ** | 6.348 * | |||||||||||

| df | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Level 1 intercept variance (SE) | 0.099 (0.010) | 0.098 (0.010) | 0.087 (0.009) | 0.083 (0.008) | 0.081 (0.008) | ||||||||||

| Level 2 intercept variance (SE) | 0.384 (0.076) | 0.217 (0.047) | 0.219 (0.047) | 0.219 (0.047) | 0.214 (0.046) | ||||||||||

| Variables | Null Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | t | Estimate | SE | t | Estimate | SE | t | Estimate | SE | t | Estimate | SE | t | |

| Intercept | 2.986 | 0.122 | 24.475 *** | 3.031 | 0.094 | 32.24 *** | 3.031 | 0.093 | 32.59 *** | 3.031 | 0.094 | 32.24 *** | 3.025 | 0.094 | 32.18 *** |

| Sex | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.214 | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.214 | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.214 | 0.004 | 0.014 | 0.285 | |||

| Age | −0.014 | 0.010 | −1.4 | −0.014 | 0.010 | −1.4 | −0.014 | 0.010 | −1.4 | −0.013 | 0.010 | −1.3 | |||

| Time | 0.004 | 0.030 | 0.133 | 0.012 | 0.028 | 0.428 | 0.021 | 0.027 | 0.778 | 0.014 | 0.027 | 0.518 | |||

| Shift | −0.019 | 0.074 | −0.256 | −0.019 | 0.074 | −0.256 | −0.019 | 0.074 | −0.256 | −0.016 | 0.073 | −0.219 | |||

| Profession | −0.530 | 0.196 | −2.704 *** | −0.530 | 0.195 | −2.704 *** | −0.532 | 0.196 | −2.714 *** | −0.532 | 0.195 | −2.728 *** | |||

| General subjective vitality | 0.549 | 0.087 | 6.310 *** | 0.549 | 0.087 | 6.310 *** | 0.548 | 0.087 | 6.298 *** | 0.538 | 0.087 | 6.183 *** | |||

| Daily WF conflict | −0.517 | 0.082 | −6.305 *** | −0.410 | 0.085 | −4.823 *** | −0.446 | 0.087 | −5.126 *** | ||||||

| Daily job EE | −0.410 | 0.117 | −3.504 *** | −0.431 | 0.116 | −3.715 *** | |||||||||

| Daily job DEP | 0.124 | 0.122 | 1.016 | 0.058 | 0.125 | 0.464 | |||||||||

| Daily job EE X WF conflict | 0.075 | 0.210 | 0.357 | ||||||||||||

| Daily job D X WF conflict | −0.526 | 0.211 | −2.492 ** | ||||||||||||

| −2 X Log(lh) | 663.542 | 582.365 | 545.852 | 533.605 | 527.465 | ||||||||||

| Difference of −2 X Log | 81.177 *** | 36.513 *** | 12.247 *** | 6.140 * | |||||||||||

| df | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Level 1 intercept variance (SE) | 0.435 (0.042) | 0.453 (0.046) | 0.377 (0.038) | 0.353 (0.036) | 0.344 (0.035) | ||||||||||

| Level 2 intercept variance (SE) | 0.747 (0.159) | 0.349 (0.088) | 0.361 (0.088) | 0.370 (0.088) | 0.364 (0.087) | ||||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blanco-Donoso, L.M.; Moreno-Jiménez, J.; Hernández-Hurtado, M.; Cifri-Gavela, J.L.; Jacobs, S.; Garrosa, E. Daily Work-Family Conflict and Burnout to Explain the Leaving Intentions and Vitality Levels of Healthcare Workers: Interactive Effects Using an Experience-Sampling Method. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041932

Blanco-Donoso LM, Moreno-Jiménez J, Hernández-Hurtado M, Cifri-Gavela JL, Jacobs S, Garrosa E. Daily Work-Family Conflict and Burnout to Explain the Leaving Intentions and Vitality Levels of Healthcare Workers: Interactive Effects Using an Experience-Sampling Method. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(4):1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041932

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlanco-Donoso, Luis Manuel, Jennifer Moreno-Jiménez, Mercedes Hernández-Hurtado, José Luis Cifri-Gavela, Stephen Jacobs, and Eva Garrosa. 2021. "Daily Work-Family Conflict and Burnout to Explain the Leaving Intentions and Vitality Levels of Healthcare Workers: Interactive Effects Using an Experience-Sampling Method" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 4: 1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041932

APA StyleBlanco-Donoso, L. M., Moreno-Jiménez, J., Hernández-Hurtado, M., Cifri-Gavela, J. L., Jacobs, S., & Garrosa, E. (2021). Daily Work-Family Conflict and Burnout to Explain the Leaving Intentions and Vitality Levels of Healthcare Workers: Interactive Effects Using an Experience-Sampling Method. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041932