Urban Retail Food Environments: Relative Availability and Prominence of Exhibition of Healthy vs. Unhealthy Foods at Supermarkets in Buenos Aires, Argentina

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Sample

2.2. Ethical Appoval

2.3. Definition of Indicators and Variables

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Management and Analysis

3. Results

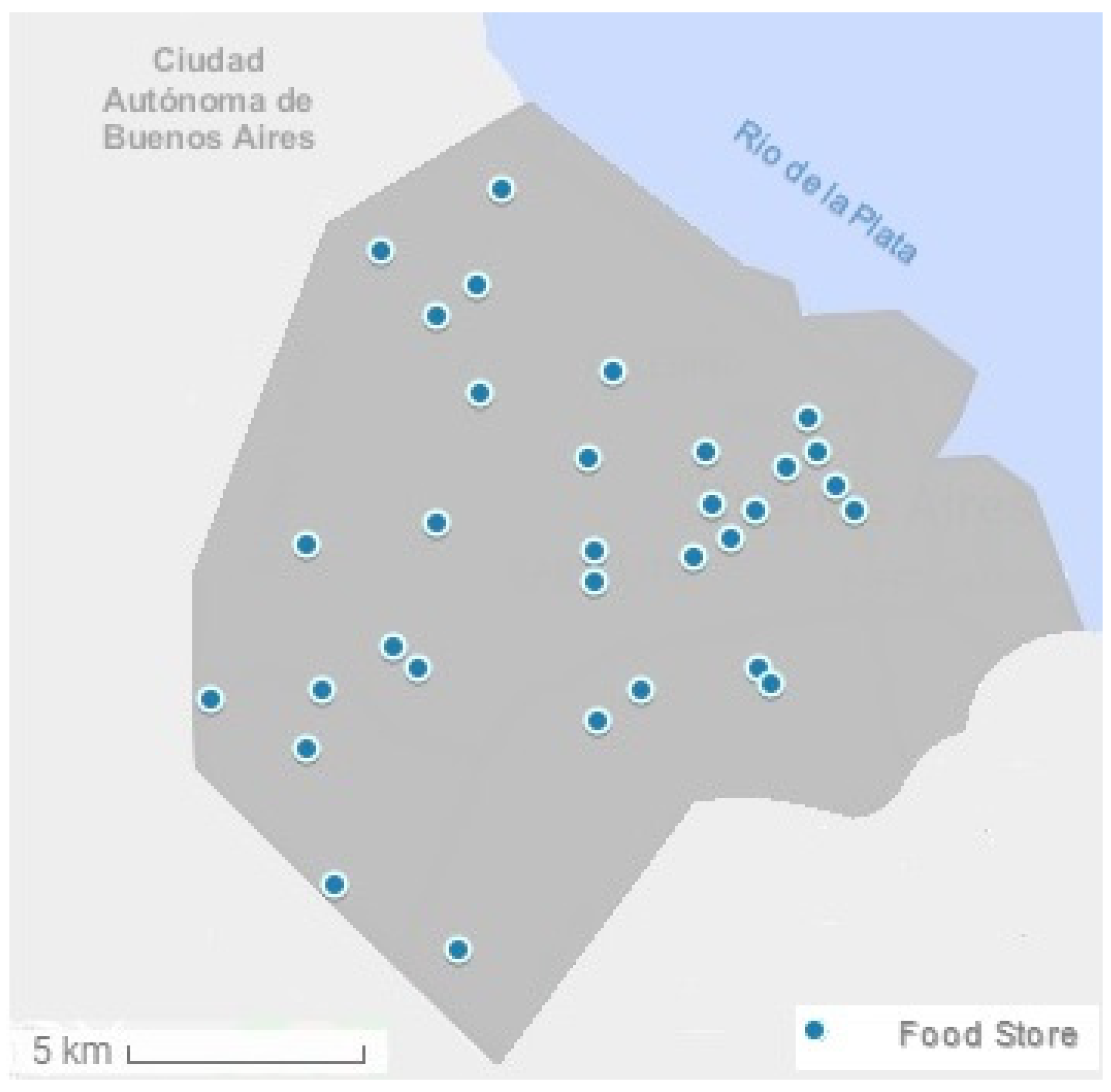

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

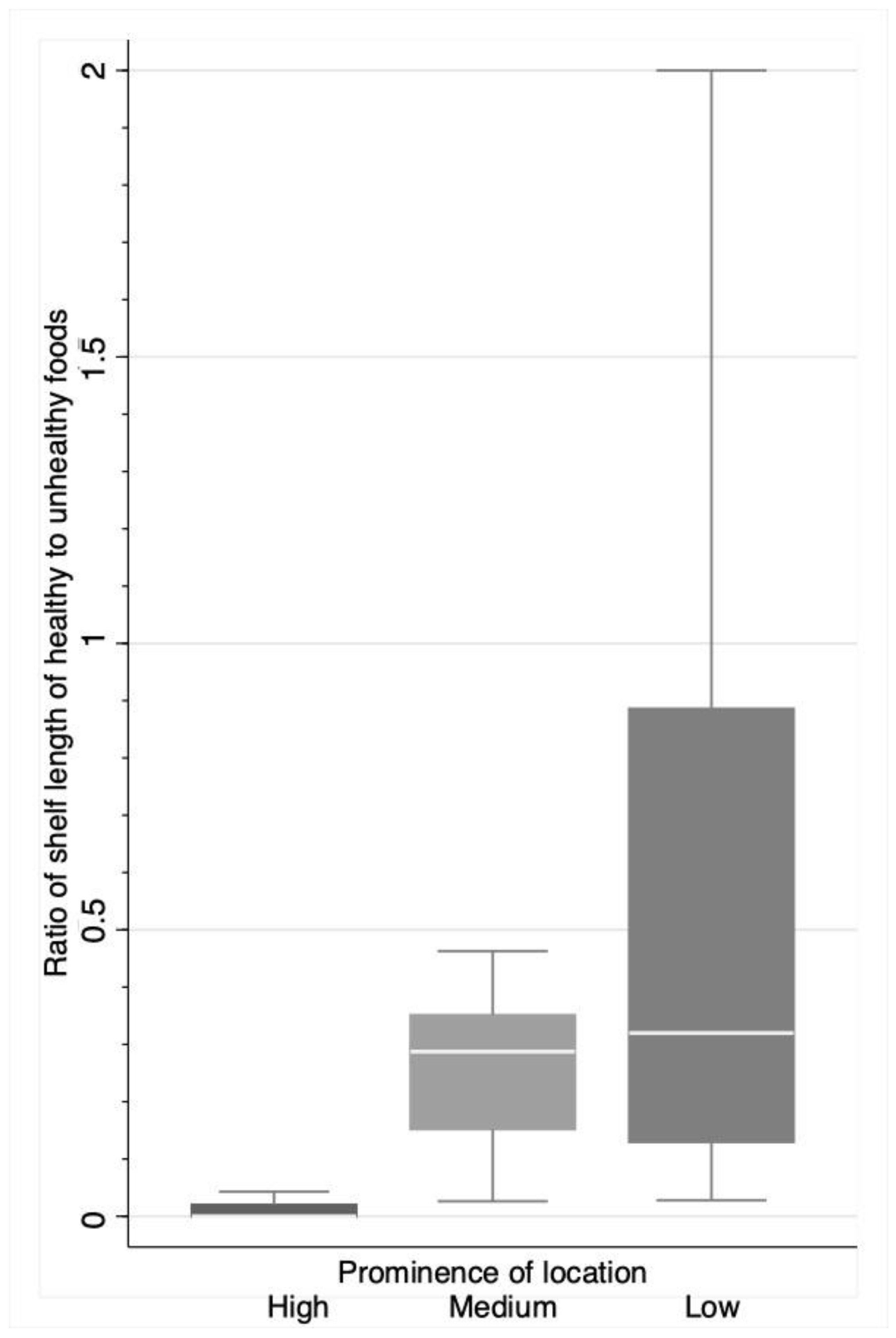

3.2. Availability of Healthy and Unhealthy Items by Prominence of Location Inside the Store

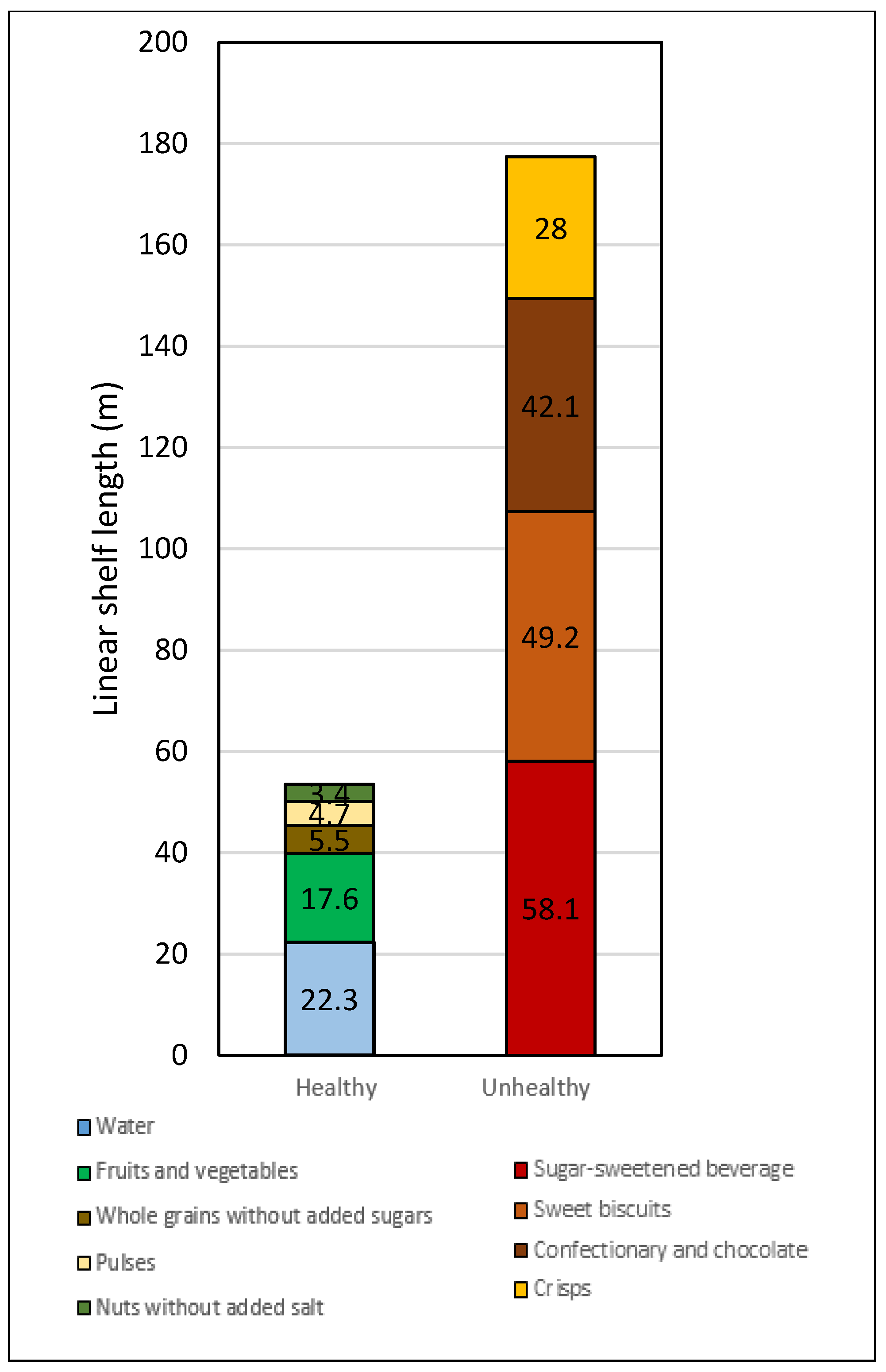

3.3. Shelf Length Assigned to Food and Beverages Items and Relative Shelf Length of Healthy and Unhealthy Items by Prominence of Location Inside the Store

3.4. Availability and Relative Linear Shelf Length of Healthy and Unhealthy Items by Supermarket Characteristics and Neighborhood Income Level

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Small-Sized | Medium/Large-Sized |

|---|---|

|

|

Appendix B

References

- Popkin, B.M.; Reardon, T. Obesity and the food system transformation in Latin America. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2018, 19, 1028–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Biryukov, S.; Abbafati, C.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Social Development Argentina. Segunda Encuesta Nacional de Nutrición y Salud. ENNyS 2: Indicadores Priorizados Septiembre 2019. Available online: http://www.msal.gob.ar/images/stories/bes/graficos/0000001602cnt-2019-10_encuesta-nacional-de-nutricion-y-salud.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Lanas, F.; Bazzano, L.; Rubinstein, A.; Calandrelli, M.; Chen, C.S.; Elorriaga, N.; Gutierrez, L.; Manfredi, J.A.; Seron, P.; Mores, N.; et al. Prevalence, distributions and determinants of obesity and central obesity in the southern cone of America. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, M.E.; Rovirosa, A.; Carmuega, E. Cambios En El Patrón de Consumo de Alimentos y Bebidas En Argentina, 1996–2013. Salud Colect. 2016, 12, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan American Health Organization. Ultra-Processed Food and Drink Products in Latin America: Trends, Impact on Obesity, Policy Implications; PAHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, P.; Machado, P.; Santos, T.; Sievert, K.; Backholer, K.; Hadjikakou, M.; Russell, C.; Huse, O.; Bell, C.; Scrinis, G.; et al. Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: Global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes. Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotthelf, S.J.; Rivas, P.C.; Tempesti, C.P. Expenditure on ultraprocessed food and relationship with socioeconomic variables in the argentine republic, 2012–2013. Actual. En Nutr. 2019, 20, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, C.; Aggarwal, A.; Walls, H.; Herforth, A.; Drewnowski, A.; Coates, J.; Kalamatianou, S.; Kadiyala, S. Concepts and critical perspectives for food environment research: A global framework with implications for action in low- and middle-income countries. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 18, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Vandevijvere, S.; Kumanyika, S.; Lobstein, T.; Neal, B.; Barquera, S.; Friel, S.; Hawkes, C.; Kelly, B.; et al. INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/Non-Communicable Diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): Overview and key principles: INFORMAS overview. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Hall, K.D.; McPherson, K.; Finegood, D.T.; Moodie, M.L.; Gortmaker, S.L. The global obesity pandemic: Shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011, 378, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D. Healthy Nutrition Environments: Concepts and Measures. Am. J. Health Promot. 2005, 19, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección Nacional de Abordaje Integral de las Enfermedades No Transmisibles-Ministerio de Salud Argentina Análisis Del Nivel de Concordancia de Sistemas de Perfil de Nutrientes Con Las Guías Alimentarias Para La Población; Ministerio de Salud: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2020.

- Ministerio de Salud Argentina. Guías Alimentarias Para La Población Argentina; Ministerio de Salud: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2016.

- Reardon, T.; Timmer, C.P.; Barrett, C.B.; Berdegué, J. The rise of supermarkets in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2003, 85, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablin, A. La rutina es el cambio Supermercadismo. Aliment. Argent. 2012, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, E.; Berges, M.; Casellas, K.; Paola, R.D.; Lupín, B.; Garrido, L.; Gentile, N. Consumer behaviour and supermarkets in Argentina. Dev. Policy Rev. 2002, 20, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, E. International expansion and strategies of discount grocery retailers: The winning models. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2003, 31, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euromonitor International. Grocery Retailers in Argentina; Euromonitor: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marrero, D. The Role of Chinese Supermarkets in the Social Integration of the Chinese Population in Buenos Aires; Transnationalism and Comparative Development in South America; SIT: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lema, S.; Vázquez, N.; Antun, C.; Giai, M.; Graciano, A.; Fraga, C.; Langer, V.; Paiva, M.; Longo, E. Factores Que Inciden En La Compra De Alimentos En Distintos Ámbitos De Comercialización Y Su Relación Con La Implementación De Educación Alimentaria Nutricional (EAN) [Factors influencing the purchase of foods in different marketing settings, and their relation to the implementation of Food and Nutrition Education (FNE )]. Diaeta BAires 2010, 28, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dirección General de Estadística y Censos; Ministerio de Hacienda y Finanzas; Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Ventas Totales, Participación Relativa En El Total Nacional, Superficie Del Área de Ventas, Bocas de Expendio y Operaciones En Supermercados. Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Enero 2007/Marzo 2020. Available online: https://www.estadisticaciudad.gob.ar/eyc/?p=24367 (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Duran, A.C.; Lock, K.; Latorre, M.d.R.D.O.; Jaime, P.C. Evaluating the use of in-store measures in retail food stores and restaurants in Brazil. Rev. Saúde Pública 2015, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, A.C.; de Almeida, S.L.; Latorre, M.d.R.D.O.; Jaime, P.C. The role of the local retail food environment in fruit, vegetable and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean. Childhood Overweight and the Retail Environment in Latin America and the Caribbean: Synthesis Report; United Nations Children’s Fund: Panama City, Panama, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Farley, T.A.; Rice, J.; Bodor, J.N.; Cohen, D.A.; Bluthenthal, R.N.; Rose, D. Measuring the food environment: Shelf space of fruits, vegetables, and snack foods in stores. J. Urban Health 2009, 86, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.J. The shelf space and strategic placement of healthy and discretionary foods in urban, urban-fringe and rural/non-metropolitan australian supermarkets. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevijvere, S.; Waterlander, W.; Molloy, J.; Nattrass, H.; Swinburn, B. Towards healthier supermarkets: A national study of in-store food availability, prominence and promotions in New Zealand. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, J.L. A brief history of food retail. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.J.; Thornton, L.E.; McNaughton, S.A.; Crawford, D. Variation in supermarket exposure to energy-dense snack foods by socio-economic position. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mah, C.L.; Luongo, G.; Hasdell, R.; Taylor, N.G.A.; Lo, B.K. A systematic review of the effect of retail food environment interventions on diet and health with a focus on the enabling role of public policies. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2019, 8, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni Mhurchu, C.; Vandevijvere, S.; Waterlander, W.; Thornton, L.E.; Kelly, B.; Cameron, A.J.; Snowdon, W.; Swinburn, B.; INFORMAS. Monitoring the availability of healthy and unhealthy foods and non-alcoholic beverages in community and consumer retail food environments globally: Monitoring food availability in retail food environments. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glanz, K.; Bader, M.D.M.; Iyer, S. Retail Grocery Store Marketing Strategies and Obesity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 42, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, A.; Hankins, S.; Jilcott, S. Measures of the consumer food store environment: A systematic review of the evidence 2000–2011. J. Community Health 2012, 37, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engler-Stringer, R.; Le, H.; Gerrard, A.; Muhajarine, N. The community and consumer food environment and children’s diet: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhurchu, C.N. INFORMAS Protocol: Food Retail Module—Retail Instore Food Availability.; The University of Auckland: Auckland, New Zealand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vandevijvere, S.; Mackenzie, T.; Mhurchu, C.N. Indicators of the relative availability of healthy versus unhealthy foods in supermarkets: A validation study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.; Sallis, J.F.; Bromby, E.; Glanz, K. Assessing reliability and validity of the gropromo audit tool for evaluation of grocery store marketing and promotional environments. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección General de Estadística y Censos; Ministerio de Hacienda y Finanzas; Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. EAH Promedio Del Ingreso per Cápita Familiar (IPCF) de Los Hogares Según Comuna. Ciudad de Buenos Aires Años 2008/2019. Available online: https://www.estadisticaciudad.gob.ar/eyc/?p=82456 (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, L.E.; Cameron, A.J.; McNaughton, S.A.; Waterlander, W.E.; Sodergren, M.; Svastisalee, C.; Blanchard, L.; Liese, A.D.; Battersby, S.; Carter, M.-A.; et al. Does the availability of snack foods in supermarkets vary internationally? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anigstein, M.S. Estrategias Familiares de Provisión de Alimentos en Hogares de Mujeres-Madres Trabajadoras de La Ciudad de Santiago de Chile. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2019, 46, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalbert-Arsenault, É.; Robitaille, É.; Paquette, M.-C. Development, reliability and use of a food environment assessment tool in supermarkets of four neighbourhoods in Montréal, Canada. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2017, 37, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rubinstein, A.; Elorriaga, N.; Garay, O.U.; Poggio, R.; Caporale, J.; Matta, M.G.; Augustovski, F.; Pichon-Riviere, A.; Mozaffarian, D. Eliminating artificial trans fatty acids in Argentina: Estimated effects on the burden of coronary heart disease and costs. Bull. World Health Organ. 2015, 93, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elorriaga, N.; Gutierrez, L.; Romero, I.; Moyano, D.; Poggio, R.; Calandrelli, M.; Mores, N.; Rubinstein, A.; Irazola, V. Collecting evidence to inform salt reduction policies in Argentina: Identifying sources of sodium intake in adults from a population-based sample. Nutrients 2017, 9, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basto-Abreu, A.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T.; Vidaña-Pérez, D.; Colchero, M.A.; Hernández-F, M.; Hernández-Ávila, M.; Ward, Z.J.; Long, M.W.; Gortmaker, S.L. Cost-effectiveness of the sugar-sweetened beverage excise tax in Mexico. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 1824–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taillie, L.S.; Reyes, M.; Colchero, M.A.; Popkin, B.; Corvalán, C. An evaluation of chile’s law of food labeling and advertising on sugar-sweetened beverage purchases from 2015 to 2017: A before-and-after study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, M.; Smith Taillie, L.; Popkin, B.; Kanter, R.; Vandevijvere, S.; Corvalán, C. Changes in the amount of nutrient of packaged foods and beverages after the initial implementation of the Chilean law of food labelling and advertising: A nonexperimental prospective study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basto-Abreu, A.; Torres-Alvarez, R.; Reyes-Sánchez, F.; González-Morales, R.; Canto-Osorio, F.; Colchero, M.A.; Barquera, S.; Rivera, J.A.; Barrientos-Gutierrez, T. Predicting obesity reduction after implementing warning labels in Mexico: A modeling study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Educación, Cultura, Ciencia y Tecnología; Ministerio de Salud y Desarrollo Social. Entornos Escolares Saludables; Gobierno de la Nación: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2019.

- Curhan, R.C. The relationship between shelf space and unit sales in supermarkets. J. Mark. Res. 1972, 9, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curhan, R.C. The effects of merchandising and temporary promotional activities on the sales of fresh fruits and vegetables in supermarkets. J. Mark. Res. 1974, 11, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.; Hutchinson, P.L.; Bodor, J.N.; Swalm, C.M.; Farley, T.A.; Cohen, D.A.; Rice, J.C. Neighborhood food environments and body mass index. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.J.; Charlton, E.; Ngan, W.W.; Sacks, G. A systematic review of the effectiveness of supermarket-based interventions involving product, promotion, or place on the healthiness of consumer purchases. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2016, 5, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, L.; Rosin, M.; Jiang, Y.; Grey, J.; Vandevijvere, S.; Waterlander, W.; Mhurchu, C.N. The effect of a shelf placement intervention on sales of healthier and less healthy breakfast cereals in supermarkets: A co-designed pilot study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 113337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics of the Supermarkets | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Type of food retail | ||

| Non-discount store | 19 | 59.3 |

| Discount store | 13 | 40.6 |

| Outlet size 1 | ||

| Small | 16 | 50.0 |

| Medium/large | 16 | 50.0 |

| Geographical Zone | ||

| North | 7 | 21.8 |

| Central | 16 | 50.0 |

| South | 9 | 28.1 |

| Neighborhood income level | ||

| ≤median income per capita | 17 | 53.1 |

| >median income per capita | 15 | 46.9 |

| Item | Any Place in the Store | Prominence 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium | Low | ||

| n | n | n | n | |

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| Water | 31 | 6 | 26 | 26 |

| 96.9 (83.8–99.9) | 18.8 (7.2–36.4) | 81.3 (63.6–92.8) | 81.3 (63.6–92.8) | |

| Fruits and vegetables | 29 | 0 | 20 | 21 |

| 90.6 (75.0–98.0) | 0 (0.0–10.9) * | 62.5 (43.7–78.9) | 65.6 (46.8–81.4) | |

| Pulses | 17 | 0 | 14 | 4 |

| 53.1 (34.7–70.9) | 0 (0.0–10.9) * | 43.8 (26.4–62.3) | 12.5 (3.5–29.9) | |

| Whole grains without added sugars | 30 | 1 | 24 | 17 |

| 93.8 (79.2–99.2) | 3.1 (0.1–16.2) | 75.0 (56.6–88.5) | 53.1 (34.7–70.9) | |

| Nuts without added salt | 26 | 2 | 19 | 6 |

| 81.2 (63.6–92.8) | 6.3 (0.8–20.8) | 59.4 (40.6–763) | 18.8 (7.2–36.4) | |

| Any healthy product | 32 | 9 | 32 | 32 |

| 100.0 (89.1–100.0) * | 28.1 (13.7–46.7) | 100.0 (89.1–100.0) * | 100.0 (89.1–100.0) * | |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages | 32 | 17 | 32 | 30 |

| 100.0 (89.1–100.0) * | 53.1 (34.7–70.9) | 100.0 (89.1–100.0) * | 93.8 (79.2–99.2) | |

| Crisps | 32 | 14 | 27 | 15 |

| 100.0 (89.1–100.0) * | 43.8 (26.4–62.3) | 84.4 (67.2–94.7) | 46.9 (29.1–65.3) | |

| Sweet biscuits | 32 | 7 | 29 | 14 |

| 100.0 (89.1–100.0) * | 21.9 (9.3–39.9) | 90.6 (75.0–98.0) | 43.8 (26.4–62.3) | |

| Confectionary and chocolate | 32 | 29 | 23 | 10 |

| 100.0 (89.1–100.0) * | 90.6 (75.0–98.0) | 71.9 (53.6–86.3) | 31.3 (16.1–50.0) | |

| Any unhealthy product | 32 | 31 | 32 | 31 |

| 100.0 (89.1–100.0) * | 96.9 (83.8–99.9) | 100.0 (89.1–100.0) * | 96.9 (83.8–99.9) | |

| Item | Any Place in the Store | Prominence 1 | p-Value 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium | Low | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Water | 22.3 (38.2) | 13.0 (6.9–19.8) | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 16.9 (30.1) | 9.8 (2.0–17.8) | 5.2 (9.2) | 2.4 (0.6–4.6) | 0.001 |

| Fruits and vegetables | 17.6 (25.9) | 10.0 (2.1–19.5) | 0.0 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 8.9 (13.7) | 3.12 (0.0–10.4) | 8.7 (14.8) | 1.2 (0.0–9.3) | 0.003 |

| Pulses | 4.7 (16.8) | 0.6 (0.0–2.3) | 0.0 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 1.9 (3.9) | 0.0 (0.0–2.2) | 2.7 (14.9) | 0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.452 |

| Whole grains without added sugars | 5.5 (10.9) | 2.8 (1.5–3.9) | 0.0 (21.2) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 3.6 (8.8) | 1.0 (0.1–2.9) | 1.9 (2.8) | 0.3 (0.0–3.3) | 0.032 |

| Nuts without added salt | 3.4 (7.6) | 1.3 (0.6–2.3) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 2.9 (7.5) | 0.8 (0.0–2.1) | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.021 |

| Healthy foods (total length) | 53.4 (85.4) | 25.9 (19.5–38.4) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.0 (0.0–0.4) | 34.2 (55.0) | 17.6 (12.0–29.5) | 19.0 (31.4) | 6.9 (2.9–18.8) | 0.002 |

| Sugar-sweetened beverage | 58.1 (82.1) | 33.6 (25.9–53.4) | 2.1 (3.1) | 0.6 (0.0–2.7) | 42.3 (68.7) | 24.4 (12.5–40.3) | 13.8 (15.8) | 10.4 (5.5–15.4) | <0.001 |

| Crisps | 28.0 (18.3) | 22.0 (15.6–31.7) | 1.3 (3.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 19.3 (19.9) | 15.6 (3.8–25.2) | 7.4 (11.3) | 0.0 (0.0–13.0) | <0.001 |

| Sweet biscuits | 49.2 (55.6) | 37.9 (28.3–49.7) | 0.9 (2.4) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 41.4 (55.2) | 32.0 (23.6–42.2) | 7.0 (15.2) | 0.0 (0.0–4.5) | <0.001 |

| Confectionary and chocolate | 42.1 (57.1) | 24.4 (15.7–44.6) | 14.9 (17.8) | 8.5 (4.3–19.0) | 19.3 (34.1) | 7.35 (0.0–20.0) | 8.0 (19.8) | 0.0 (0.0–7.2) | 0.1948 |

| Unhealthy products (total lenght) | 177.5 (20.3) | 115.0 (90.5–178.2) | 19.1 (21.9) | 10.8 (5.8–22.5) | 122.3 (166.1) | 77.5 (54.0–116.4) | 36.0 (36.5) | 27.8 (11.3–51.4) | <0.001 |

| Ratio healthy/unhealthy products | 0.255 (0.130) | 0.232 (0.169–0.283) | 0.013 (0.026) | 0.0 (0.0–0.014) | 0.417 (0.753) | 0.271 (0.150–0.350) | 0.846 (1.366) 2 | 0.320 (0.130–0.886) | 0.003 |

| Subgroups | n | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 32 | 0.255 (0.130) | 0.232 (0.169–0.284) | |

| Location by income level | 0.0329 | |||

| Lower-income neighborhoods | 17 | 0.208 (0.086) | 0.206 (0.163–0.246) | |

| Higher-income neighborhoods | 15 | 0.309 (0.152) | 0.273 (0.208–0.359) | |

| Outlet size | 0.9622 | |||

| Small | 16 | 0.246 (0.111) | 0.226 (0.188–0.276) | |

| Medium/Large | 16 | 0.264 (0.150) | 0.244 (0.151–0.326) | |

| Food retail type | 0.2577 | |||

| Non-discount supermarket | 19 | 0.246 (0.143) | 0.206 (0.141–0.306) | |

| Discount supermarket | 13 | 0.268 (0.113) | 0.263 (0.225–0.277) | |

| Supermarket Chain 1 | 0.0268 | |||

| A | 8 | 0.199 (0.068) | 0.188 (0.152–0.248) | |

| B | 6 | 0.379 (0.177) | 0.396 (0.246–0.553) | |

| C | 13 | 0.268 (0.113) | 0.263 (0.225–0.277) | |

| D | 5 | 0.161 (0.068) | 0.168 (0.134–0.197) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elorriaga, N.; Moyano, D.L.; López, M.V.; Cavallo, A.S.; Gutierrez, L.; Panaggio, C.B.; Irazola, V. Urban Retail Food Environments: Relative Availability and Prominence of Exhibition of Healthy vs. Unhealthy Foods at Supermarkets in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030944

Elorriaga N, Moyano DL, López MV, Cavallo AS, Gutierrez L, Panaggio CB, Irazola V. Urban Retail Food Environments: Relative Availability and Prominence of Exhibition of Healthy vs. Unhealthy Foods at Supermarkets in Buenos Aires, Argentina. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(3):944. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030944

Chicago/Turabian StyleElorriaga, Natalia, Daniela L. Moyano, María V. López, Ana S. Cavallo, Laura Gutierrez, Camila B. Panaggio, and Vilma Irazola. 2021. "Urban Retail Food Environments: Relative Availability and Prominence of Exhibition of Healthy vs. Unhealthy Foods at Supermarkets in Buenos Aires, Argentina" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 3: 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030944

APA StyleElorriaga, N., Moyano, D. L., López, M. V., Cavallo, A. S., Gutierrez, L., Panaggio, C. B., & Irazola, V. (2021). Urban Retail Food Environments: Relative Availability and Prominence of Exhibition of Healthy vs. Unhealthy Foods at Supermarkets in Buenos Aires, Argentina. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030944