The Relationships among Self-Worth Contingency on Others’ Approval, Appearance Comparisons on Facebook, and Adolescent Girls’ Body Esteem: A Cross-Cultural Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Media, Appearance Comparison, and Body Esteem

1.2. Self-Worth Contingency on Others’ Approval

1.3. Cultural Differences

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

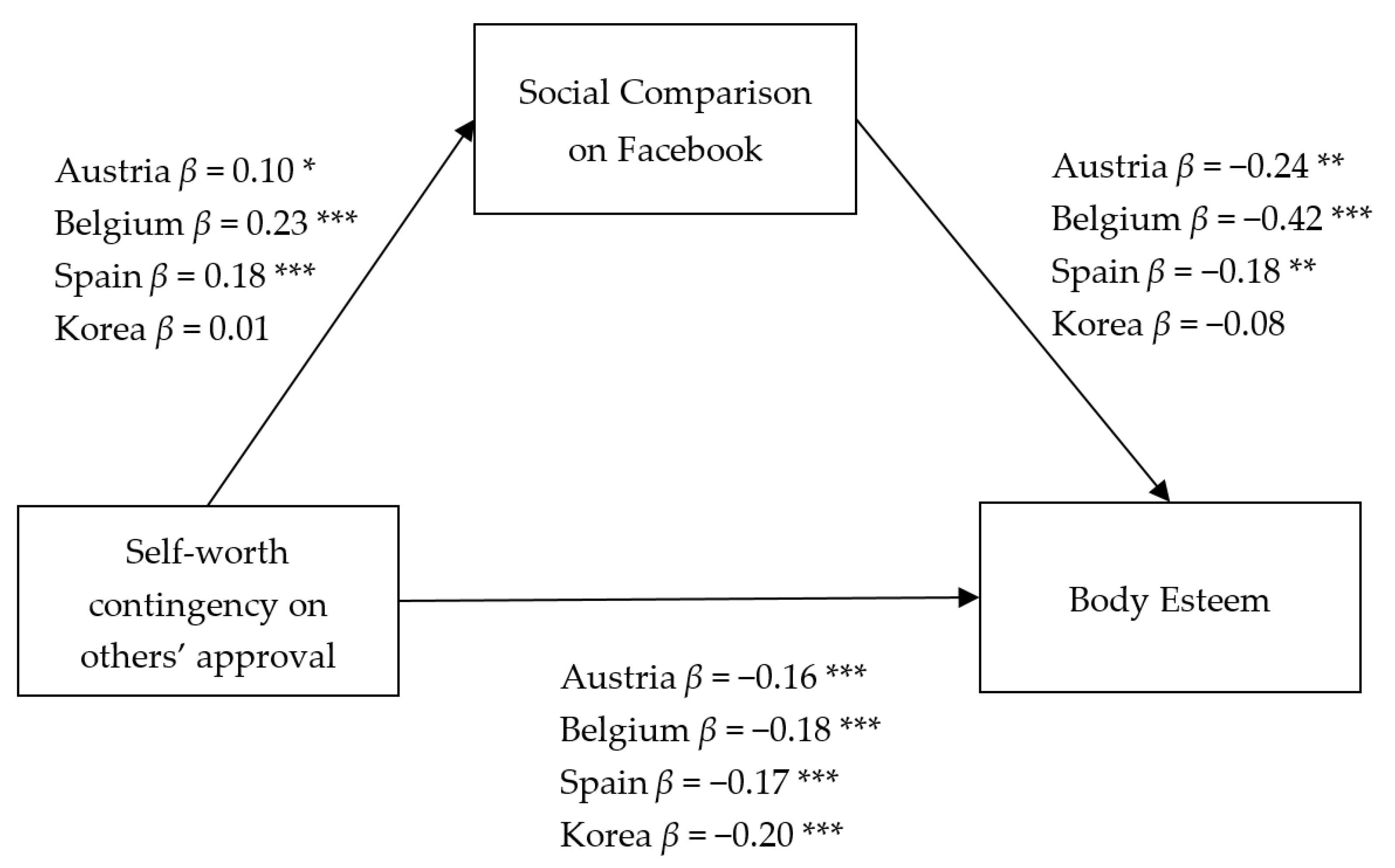

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, A.S.V. Body perceptions, weight control behavior, and changes in adolescents’ psychological well-being over time: A longitudinal examination of gender. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helgeson, V.S. The Psychology of Gender, 3rd ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, D.A.; Tiggemann, M. Idealized media images and adolescent body image: “Comparing” boys and girls. Body Image 2004, 1, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddon, L.; Hasebrink, U.; Ólafsson, K.; Neill, B.; Šmahel, D.; Staksrud, E. EU Kids Online: Findings, Methods, Recommendations; The London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Respond 2018. Is Our Communication Channel an Instant Messenger? Statistics Korea. 2018. Available online: http://naver.me/5P5dAMIM (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Perloff, R.M. Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: Theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research. Sex Roles 2014, 71, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barash, V.; Ducheneaut, N.; Isaacs, E.; Bellotti, V. Faceplant: Impression (Mis)management in Facebook Status Updates. In Proceedings of the Fourth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Washington, DC, USA, 23–26 May 2010; Available online: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/14037/13886 (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Jordan, A.H.; Monin, B.; Dweck, C.S.; Lovett, B.J.; John, O.P.; Gross, J.J. Misery has more company than people think: Underestimating the prevalence of others’ negative emotions. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.R.J.; Shim, M.; Joo, Y.K.; Park, S.G. Who puts the best “face” forward on Facebook?: Positive self-presentation in online social networking and the role of self-consciousness, actual-to-total Friends ratio, and culture. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 39, 413–423. [Google Scholar]

- Schmuck, D.; Karsay, K.; Matthes, J.; Stevic, A. “Looking Up and Feeling Down”. The influence of mobile social networking site use on upward social comparison, self-esteem, and well-being of adult smartphone users. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haferkamp, N.; Eimler, S.C.; Papadakis, A.M.; Kruck, J.V. Men are from Mars, women are from Venus? Examining gender differences in self-presentation on social networking sites. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, G.; Tiggemann, M. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image 2016, 17, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryding, F.C.; Kuss, D.J. The use of social networking sites, body image dissatisfaction, and body dysmorphic disorder: A systematic review of psychological research. Psychol. Pop. Media 2020, 9, 412–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.A.; Wang, J.L. Cultural differences in social networking site use: A comparative study of China and the United States. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 910–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.E.; Park, H.W. A qualitative analysis of cross-cultural new media research: SNS use in Asia and the West. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 2319–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, J.; Luhtanen, R.K.; Cooper, M.L.; Bouvrette, A. Contingencies of self-worth in college students: Theory and measurement. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 894–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, H.; Neighbors, C.; Knee, C.R. Appearance-related social comparison: The role of contingent self-esteem and self-perceptions of attractiveness. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 30, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, M.P.; Murnen, S.K. “Everybody knows that mass media are/are not [pick one] a cause of eating disorders”: A critical review of evidence for a causal link between media, negative body image, and disordered eating in females. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 28, 9–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, G.G.; Levine, M.P.; Sánchez, C.D.; Fauquet, J. Influence of mass media on body image and eating disordered attitudes and behaviors in females: A review of effects and processes. Media Psychol. 2010, 13, 387–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlett, C.P.; Vowels, C.L.; Saucier, D.A. Meta-analyses of the effects of media images on men’s body-image concerns. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 27, 279–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, H.; Halliwell, E.; Stirling, E. Understanding the impact of thin media models on women’s body-focused affect: The roles of thin-ideal internalization and weight-related self-discrepancy activation in experimental exposure effects. J. Soc. Clin. 2009, 28, 43–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blond, A. Impacts of exposure to images of ideal bodies on male body dissatisfaction: A review. Body Image 2008, 5, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabe, S.; Ward, M.L.; Hyde, J.S. The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groesz, L.M.; Levine, M.P.; Murnen, S.K. The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2002, 31, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieler, M.; Choi, J. Broadening the scope of social media effect research on body image concerns. Sex Roles 2014, 71, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C.; Lampe, C. The Benefits of Facebook “Friends:” Social Capital and College Students’ Use of Online Social Network Sites. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2007, 12, 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L. Adolescence, 8th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cash, T.F.; Cash, D.W.; Butters, J.W. “Mirror, Mirror, on the Wall...?” Contrast Effects and Self-Evaluations of Physical Attractiveness. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1983, 9, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.; Newton, J.T.; Slater, A. “Selfie”-objectification: The role of selfies in self-objectification and disordered eating in young women. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 79, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, E.P.; Gray, J. Facebook photo activity associated with body image disturbance in adolescent girls. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Chock, T.M. Body image 2.0: Associationas between social grooming on Facebook and body image concerns. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, C. Facebook, body esteem, and body surveillance in adult women: The moderating role of self-compassion and appearance-contingent self-worth. Body Image 2019, 29, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, S.A.; Paxton, S.J.; Wertheim, E.H.; Masters, J. Photoshopping the selfie: Self photo editing and photo investment are associated with body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 48, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L.; Li, P.; Loh, R.S.M.; Chua, T.H.H. A study of Singapore adolescent girls’ selfie practices, peer appearance comparisons, and body esteem on Instagram. Body Image 2019, 29, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. The theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, S.C.; Keery, H.; Thompson, J.K. The media’s role in body image and eating disorders. In Featuring Females: Feminist Analyses of Media; Cole, E., Daniel, J.H., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, M.; Thornton, L.; Choudhury, M.D.; Teevan, J.; Bulik, C.; Levinson, C.A.; Zerwas, S. Facebook use and disordered eating in college-aged women. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 57, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, T.G.; Kalin, R.; Morrison, M.A. Body-image evaluation and body-image investment among adolescents: A test of sociocultural and social comparison theories. Adolescence 2004, 39, 571–572. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, R.; Blaszczynski, A. Comparative effects of Facebook and conventional media on body image dissatisfaction. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S.S.; Lee, E.W.J.; Liao, Y. Social network sites, friends, and celebrities: The roles of social comparison and celebrity involvement in adolescents’ body image dissatisfaction. Soc. Media Soc. 2016, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y. How do people compare themselves with others on social network sites?: The case of Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 32, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanat, M.Y.; Almog, L.; Cohen, R.; Amichai, H.Y. Contingent self-worth and Facebook addiction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 88, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.D.; Ricciardelli, L.A. Social comparisons, appearance related comments, contingent self-esteem and their relationship with body dissatisfaction and eating disturbance among women. Eat. Behav. 2010, 11, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overstreet, N.M.; Quinn, D.M. Contingencies of self-worth and appearance concerns: Do domains of self-worth matter? Psychol. Women Q. 2012, 36, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, K.J.; Tylka, T.L. Self-compassion moderates body comparison and appearance self-worth’s inverse relationships with body appreciation. Body Image 2015, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noser, A.; Zeigler, H.V. Investing in the ideal: Does objectified body consciousness mediate the association between appearance contingent self-worth and appearance self-esteem in women? Body Image 2014, 11, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leary, M.R.; Baumeister, R.F. The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Homan, K.J.; Tylka, T.L. Development and exploration of the gratitude model of body appreciation in women. Body Image 2018, 25, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, T.; Mallery, P. Social comparison, individualism-collectivism, and self-esteem in China and the United States. Curr. Psychol. 1999, 18, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Lehman, D.R. Culture and social comparison seeking: The role of self-motives. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.K.; Heinberg, L.; Tantleff, D.S. The physical appearance comparison scale. Behav. Ther. 1991, 14, 174. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson, B.K.; Mendelson, M.J.; White, D.R. Body-esteem scale for adolescents and adults. J. Personal. Assess. 2001, 76, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus Version 8 User’s Guide; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J.; Muñoz, M.E.; Garza, A.; Galindo, M. Concurrent and prospective analyses of peer, television and social media influences on body dissatisfaction, eating disorder symptoms and life satisfaction in adolescent girls. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamplin, N.C.; Lean, S.A.; Paxton, S.J. Social media literacy protects against the negative impact of exposure to appearance ideal social media images in young adult women but not men. Body Image 2018, 26, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M.; Anderberg, I. Social media is not real: The effect of ‘Instagram vs reality’images on women’s social comparison and body image. New Media Soc. 2020, 22, 2183–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | BMI | Media Use | Others’ Approval | Social Comparison | Body Esteem | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Age | ||||||

| BMI | 0.26 ** | ||||||

| Media Use | −0.08 | 0.10 | |||||

| Others’ Approval | −0.09 | 0.01 | 0.04 | (0.84) | |||

| Social Comparison | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.19 * | −0.17 ** | (0.84) | ||

| Body Esteem | −0.15 * | −0.35 ** | 0.02 | 0.29 ** | −0.25 ** | (0.89) | |

| Belgium | Age | ||||||

| BMI | 0.24 ** | ||||||

| Media Use | 0.01 | 0.09 | |||||

| Others’ Approval | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.02 | (0.84) | |||

| Social Comparison | 0.21 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.06 | −0.38 ** | (0.81) | ||

| Body Esteem | −0.09 | −0.33 ** | 0.00 | 0.39 ** | −0.49 | (0.89) | |

| Spain | Age | ||||||

| BMI | 0.09 | ||||||

| Media Use | 0.01 | 0.03 | |||||

| Others’ Approval | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.05 | (0.83) | |||

| Social Comparison | 0.14 * | 0.01 | 0.16 | −0.29 | (0.82) | ||

| Body Esteem | −0.05 | −0.22 ** | 0.02 | 0.30 | −0.23 | (0.88) | |

| South Korea | Age | ||||||

| BMI | 0.16 * | ||||||

| Media Use | 0.15 * | 0.04 | |||||

| Others’ Approval | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.10 | (0.91) | |||

| Social Comparison | 0.34 ** | 0.10 | 0.30 * | −0.01 | (0.90) | ||

| Body Esteem | −0.14 | −0.20 ** | 0.18 * | 0.37 ** | 0.04 | (0.86) |

| Variables | Austria (N = 199) | Belgium (N = 292) | Spain (N = 306) | South Korea (N = 184) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | M (SD) | 14.11 (1.21) | 12.69 (0.67) | 14.06 (0.84) | 12.96 (0.84) |

| Range | 12–16 | 11–15 | 12–15 | 12–14 | |

| BMI | M (SD) | 20.41 (3.39) | 18.47 (2.94) | 20.05 (2.76) | 19.90 (2.64) |

| Range | 14.30–37.04 | 13.07–31.25 | 14.06–31.64 | 14.34–28.35 | |

| Media Use | M (SD) | 4.83 (1.96) | 5.02 (1.51) | 4.66 (1.84) | 5.17 (2.19) |

| Range | 2–13 | 2–11 | 2–12 | 2–14 | |

| Others’ Approval | M (SD) | 0.18 (0.18) | −0.33 (1.34) | −0.10 (1.42) | −0.72 (1.48) |

| Range | −3.49–2.51 | −3.16–2.51 | −3.49–2.51 | −3.49–2.51 | |

| Social Comparison | M (SD) | 0.28 (0.91) | 0.23 (0.90) | 0.20 (0.89) | −0.05 (0.89) |

| Range | −0.76–2.49 | −0.76–3.24 | −0.76–3.24 | −0.76–2.74 | |

| Body Esteem | M (SD) | 3.21 (1.01) | 3.27 (0.92) | 3.28 (0.92) | 2.69 (0.86) |

| Range | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prieler, M.; Choi, J.; Lee, H.E. The Relationships among Self-Worth Contingency on Others’ Approval, Appearance Comparisons on Facebook, and Adolescent Girls’ Body Esteem: A Cross-Cultural Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030901

Prieler M, Choi J, Lee HE. The Relationships among Self-Worth Contingency on Others’ Approval, Appearance Comparisons on Facebook, and Adolescent Girls’ Body Esteem: A Cross-Cultural Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(3):901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030901

Chicago/Turabian StylePrieler, Michael, Jounghwa Choi, and Hye Eun Lee. 2021. "The Relationships among Self-Worth Contingency on Others’ Approval, Appearance Comparisons on Facebook, and Adolescent Girls’ Body Esteem: A Cross-Cultural Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 3: 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030901

APA StylePrieler, M., Choi, J., & Lee, H. E. (2021). The Relationships among Self-Worth Contingency on Others’ Approval, Appearance Comparisons on Facebook, and Adolescent Girls’ Body Esteem: A Cross-Cultural Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030901