Co-Creation of a Multi-Component Health Literacy Intervention Targeting Both Patients with Mild to Severe Chronic Kidney Disease and Health Care Professionals

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Eligibility and Recruitment

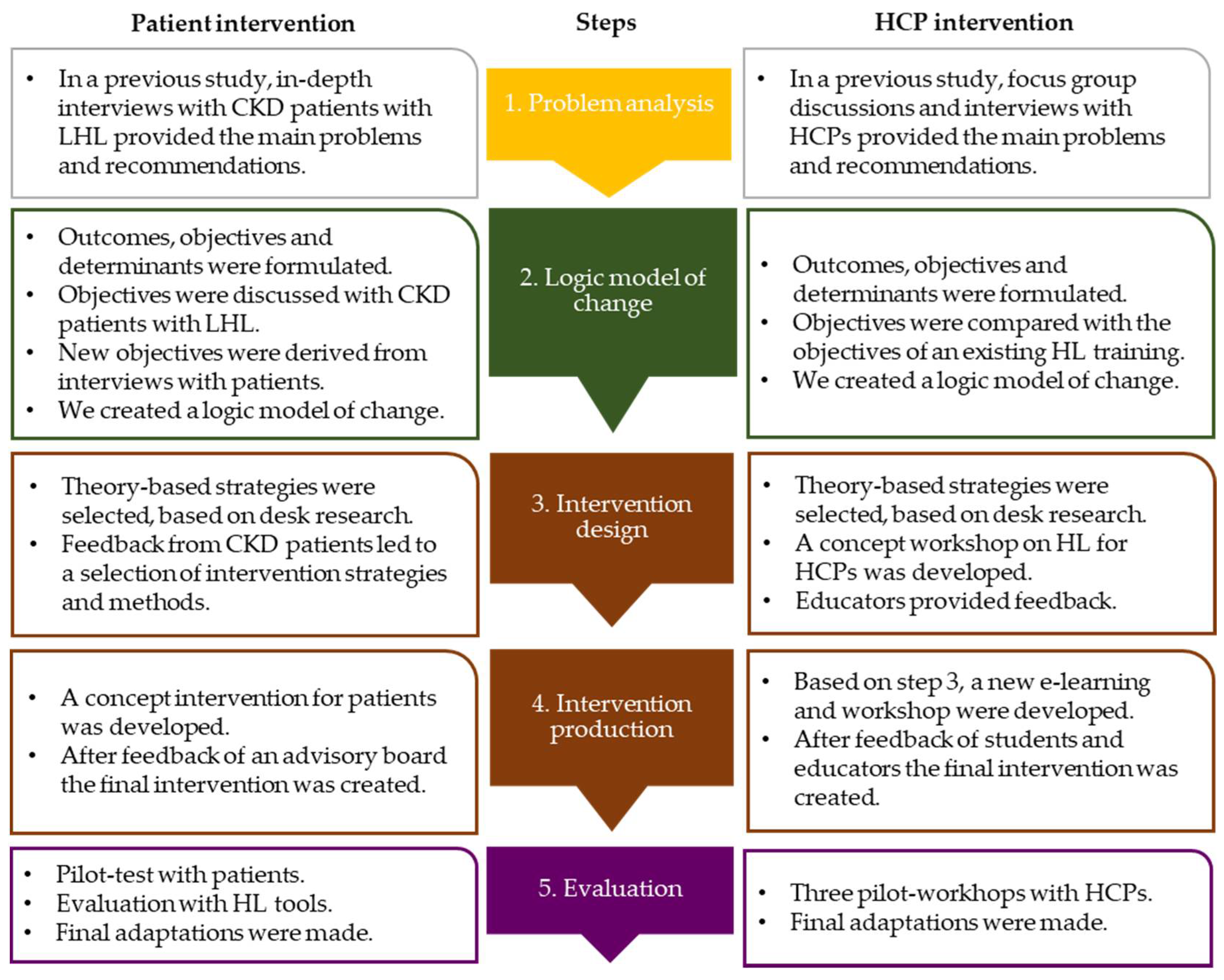

2.2. Study Procedure

2.2.1. Procedure for the Patient Intervention

2.2.2. Procedure for the HCP Intervention

2.2.3. Synthesis of the Results

2.3. Measures

3. Results

3.1. Background Characteristics

3.2. Results for the Patient Intervention

3.2.1. Step 2: Logic Model of Change

3.2.2. Step 3: Program design

Patient with moderate CKD, male, 67 years: ‘I need videos or pictures to understand. I do not read often. If I do, the information will not stick. The video I just saw made things clear’.

Patient with moderate CKD, male, 81 years, about the card to support consultations: ‘This card can help, because I am older. I sometimes don’t know what to say and I have problems remembering everything’.

Patient with severe CKD, male, 75 years: ‘Group education is not for me. I would feel uncomfortable, and not contribute much. I prefer to do it by myself or with the help of my wife’.

3.2.3. Step 4: Program Production

- (1)

- Component one and two for patients: a website and brochure with many visual strategies, such as animations and photo stories. These consisted of two parts. Part one was intended to meet our aim of improving awareness and understanding of CKD and the importance of lifestyle and medication. Part two aimed to explain lifestyle and medication, and to gain competence in communicating with HCPs effectively.

- (2)

- Component three: a card to improve consultations. This card helps patients to prepare and discuss self-management actions, needs and barriers, and HCPs to summarize information and actions for self-management. This card enables the patient to develop practical competences and helps to maintain self-management changes.

3.2.4. Step 5: Evaluation of the Intervention

Patient with moderate CKD, female, 47 years: ‘I learned a lot from this program. I learned about the functioning of the kidneys, and I think it is good to know what information I should share with the doctor’.

Patient with moderate CKD, male, 77 years: ‘The general practitioner never extensively discussed my kidney problems. So when I used the intervention, I was wondering to what extent it was for me’.

3.3. Results for the HCP Intervention

3.3.1. Step 2: Logic Model of Change

- HCPs have awareness and knowledge of health literacy and its consequences.

- HCPs know and apply strategies to identify patients with LHL.

- HCPs know and apply tailored strategies to improve awareness, knowledge and self-management, as indicated behind the objectives in Table 2.

3.3.2. Step 3: Program Design

3.3.3. Step 4: Program Production

3.3.4. Step 5: Evaluation of the Intervention

3.4. Synthesis of the Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taylor, D.M.; Fraser, S.D.S.; Bradley, J.A.; Bradley, C.; Draper, H.; Metcalfe, W.; Oniscu, G.C.; Tomson, C.R.V.; Ravanan, R.; Roderick, P.J. A Systematic Review of the Prevalence and Associations of Limited Health Literacy in CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 12, 1070–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ricardo, A.C.; Yang, W.; Lora, C.M.; Gordon, E.J.; Diamantidis, C.J.; Ford, V.; Kusek, J.W.; Lopez, A.; Lustigova, E.; Nessel, L.; et al. Limited health literacy is associated with low glomerular filtration in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study. Clin. Nephrol. 2014, 81, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devraj, R.; Borrego, M.; Vilay, A.M.; Gordon, E.J.; Pailden, J.; Horowitz, B. Relationship between Health Literacy and Kidney Function. Nephrology 2015, 20, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanaugh, K.L.; Wingard, R.L.; Hakim, R.M.; Eden, S.; Shintani, A.; Wallston, K.A.; Huizinga, M.M.; Elasy, T.A.; Rothman, R.L.; Ikizler, T.A. Low health literacy associates with increased mortality in ESRD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 1979–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kwan, B.; Frankish, J.; Rootman, I.; Zumbo, B.; Kelly, K.; Begoray, D.; Kazanijan, A.; Mullet, J.; Hayes, M. The Development and Validation of Measures of “Health Literacy” in Different Populations. Available online: https://blogs.ubc.ca/frankish/files/2010/12/HLit-final-report-2006-11-24.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Jager, M.; de Zeeuw, J.; Tullius, J.; Papa, R.; Giammarchi, C.; Whittal, A.; de Winter, A.F. Patient Perspectives to Inform a Health Literacy Educational Program: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demian, M.N.; Shapiro, R.J.; Thornton, W.L. An observational study of health literacy and medication adherence in adult kidney transplant recipients. Clin. Kidney J. 2016, 9, 858–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrauben, S.J.; Hsu, J.Y.; Wright Nunes, J.; Fischer, M.J.; Srivastava, A.; Chen, J.; Charleston, J.; Steigerwalt, S.; Tan, T.C.; Fink, J.C.; et al. Health Behaviors in Younger and Older Adults With CKD: Results From the CRIC Study. Kidney Int. Rep. 2019, 4, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lai, A.Y.; Ishikawa, H.; Kiuchi, T.; Mooppil, N.; Griva, K. Communicative and critical health literacy, and self-management behaviors in end-stage renal disease patients with diabetes on hemodialysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 91, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.; Wright, C.; Sheasby, J.; Turner, A.; Hainsworth, J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: A review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2002, 48, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, M.T.; Newton, K.S. Supporting self-management in patients with chronic illness. Am. Fam. Physician 2005, 72, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, H.; Yano, E.; Fujimori, S.; Kinoshita, M.; Yamanouchi, T.; Yoshikawa, M.; Yamazaki, Y.; Teramoto, T. Patient health literacy and patient–physician information exchange during a visit. Fam. Pract. 2009, 26, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schillinger, D.; Bindman, A.; Wang, F.; Stewart, A.; Piette, J. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician–patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2004, 52, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, C. Teaching health care professionals about health literacy: A review of the literature. Nurs. Outlook 2011, 59, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynia, M.K.; Osborn, C.Y. Health Literacy and Communication Quality in Health Care Organizations. J. Health Commun. 2010, 15, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boonstra, M.D.; Reijneveld, S.A.; Westerhuis, R.; Tullius, J.M.; Vervoort, J.P.M.; Navis, G.; de Winter, A.F. A longitudinal qualitative study to explore and optimize self-management in mild to end stage chronic kidney disease patients with limited health literacy: Perspectives of patients and health care professionals. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 105, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonstra, M.D.; Reijneveld, S.A.; Foitzik, E.M.; Westerhuis, R.; Navis, G.; de Winter, A.F. How to tackle health literacy problems in chronic kidney disease patients? A systematic review to identify promising intervention targets and strategies. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2020, 36, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patzer, R.E.; McPherson, L.; Basu, M.; Mohan, S.; Wolf, M.; Chiles, M.; Russell, A.; Gander, J.C.; Friedewald, J.J.; Ladner, D.; et al. Effect of the iChoose Kidney decision aid in improving knowledge about treatment options among transplant candidates: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Transplant. 2018, 18, 1954–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muscat, D.M.; Lambert, K.; Shepherd, H.; McCaffery, K.J.; Zwi, S.; Liu, N.; Sud, K.; Saunders, J.; O’Lone, E.; Kim, J.; et al. Supporting patients to be involved in decisions about their health and care: Development of a best practice health literacy App for Australian adults living with Chronic Kidney Disease. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2020, 32, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameling, J.M.; Auguste, P.; Ephraim, P.L.; Lewis-Boyer, L.; DePasquale, N.; Greer, R.C.; Crews, D.C.; Powe, N.R.; Rabb, H.; Boulware, L.E. Development of a decision aid to inform patients’ and families’ renal replacement therapy selection decisions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2012, 12, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robinson, J.K.; Friedewald, J.J.; Desai, A.; Gordon, E.J. Response Across the Health-Literacy Spectrum of Kidney Transplant Recipients to a Sun-Protection Education Program Delivered on Tablet Computers: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Cancer 2015, 1, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eneanya, N.D.; Percy, S.G.; Stallings, T.L.; Wang, W.; Steele, D.J.R.; Germain, M.J.; Schell, J.O.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Volandes, A.E. Use of a Supportive Kidney Care Video Decision Aid in Older Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Nephrol. 2020, 51, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandar, J.J.; Ludwig, D.A.; Aguirre, J.; Mattiazzi, A.; Bielecka, M.; Defreitas, M.; Delamater, A.M. Assessing the link between modified ‘Teach Back’ method and improvement in knowledge of the medical regimen among youth with kidney transplants: The application of digital media. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1035–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, G.M.; Tahir, M.J.; Lewis, R.M.; Samoson, D.; Temple, H.; Forman, M.R. Quality of Life after Dietary Self-Management Intervention for Persons with Early Stage CKD. Nephrol. Nurs. J. 2019, 46, 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, M.H.; Urstad, K.H.; Larsen, M.H.; Henriksen, G.F.; Engebretsen, E.; Ødemark, J.; Stenehjem, A.-E.; Reisæter, A.V.; Nordlie, A.; Wahl, A.K. Intervening on health literacy by knowledge translation processes in kidney transplantation: A feasibility study. J. Ren. Care 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Meer, L.; Nieboer, A.P.; Finkenflügel, H.; Cramm, J.M. The importance of person-centred care and co-creation of care for the well-being and job satisfaction of professionals working with people with intellectual disabilities. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 32, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, E.B.-N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durand, M.-A.; Carpenter, L.; Dolan, H.; Bravo, P.; Mann, M.; Bunn, F.; Elwyn, G. Do Interventions Designed to Support Shared Decision-Making Reduce Health Inequalities? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clement, S.; Ibrahim, S.; Crichton, N.; Wolf, M.; Rowlands, G. Complex interventions to improve the health of people with limited literacy: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 75, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheridan, S.L.; Halpern, D.J.; Viera, A.J.; Berkman, N.D.; Donahue, K.E.; Crotty, K. Interventions for Individuals with Low Health Literacy: A Systematic Review. J. Health Commun. 2011, 16, 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Haines, A.; Kinmonth, A.L.; Sandercock, P.; Spiegelhalter, D.; Tyrer, P. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ 2000, 321, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bartholomew, L.K.; Parcel, G.S.; Kok, G.; Gottlieb, N.H. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach, 2nd ed.; Schaalma, H., Markham, C., Tyrrell, S., Shegog, R., Fernández, M., Mullen, P.D., Gonzales, A., Tortolero-Luna, G., Partida, S., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006; ISBN 0-7879-7899-X. [Google Scholar]

- Chinn, D.; McCarthy, C. All Aspects of Health Literacy Scale (AAHLS): Developing a tool to measure functional, communicative and critical health literacy in primary healthcare settings. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 90, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.T.; Ruder, T.; Escarce, J.J.; Ghosh-Dastidar, B.; Sherman, D.; Elliott, M.; Bird, C.E.; Fremont, A.; Gasper, C.; Culbert, A.; et al. Developing predictive models of health literacy. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009, 24, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Medicine, I. Of Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion; Nielsen-Bohlman, L., Panzer, A.M., Kindig, D.A., Eds.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-309-28332-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rudd, R.E.; Oelschlegel, S.; Grabeel, K.L.; Tester, E.; Heidel, E. The HLE2 Assessment Tool. Available online: https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/135/2019/05/april-30-FINAL_The-Health-Literacy-Environment2_Locked.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Kaper, M.S.; Sixsmith, J.; Koot, J.A.R.; Meijering, L.B.; van Twillert, S.; Giammarchi, C.; Bevilacqua, R.; Barry, M.M.; Doyle, P.; Reijneveld, S.A.; et al. Developing and pilot testing a comprehensive health literacy communication training for health professionals in three European countries. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaper, M.S.; Winter, A.F.; de Bevilacqua, R.; Giammarchi, C.; McCusker, A.; Sixsmith, J.; Koot, J.A.R.; Reijneveld, S.A. Positive Outcomes of a Comprehensive Health Literacy Communication Training for Health Professionals in Three European Countries: A Multi-centre Pre-post Intervention Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Haes, H.; Bensing, J. Endpoints in medical communication research, proposing a framework of functions and outcomes. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 74, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Diclemente, C.C. The Transtheoretical Approach. In Handbook of Psychotherapy Integration; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 147–171. ISBN 9780190230258. [Google Scholar]

- Koops, R.; Jagt, V.; Winter, A.F.; de Reijneveld, S.A.; John, C.J.; Jansen, C.J.M.; Koops, R.; Jagt, V.; De Winter, A.F.; Reijneveld, S.A.; et al. Development of a Communication Intervention for Older Adults with Limited Health Literacy: Photo Stories to Support Doctor—Patient Communication Development of a Communication Intervention for Older Adults With Limited Health Literacy: Photo Stories t. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Visscher, B.B.; Steunenberg, B.; Heijmans, M.; Hofstede, J.M.; Devillé, W.; van der Heide, I.; Rademakers, J. Evidence on the effectiveness of health literacy interventions in the EU: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geboers, B.; Reijneveld, S.; Koot, J.; de Winter, A. Moving towards a Comprehensive Approach for Health Literacy Interventions: The Development of a Health Literacy Intervention Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Wolf, M.S. The Causal Pathways Linking Health Literacy to Health Outcomes. Am. J. Health Behav. 2007, 31, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackert, M.; Ball, J.; Lopez, N. Health literacy awareness training for healthcare workers: Improving knowledge and intentions to use clear communication techniques. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 3, e225–e228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taggart, J.; Williams, A.; Dennis, S.; Newall, A.; Shortus, T.; Zwar, N.; Denney-Wilson, E.; Harris, M.F. A systematic review of interventions in primary care to improve health literacy for chronic disease behavioral risk factors. BMC Fam. Pract. 2012, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Coleman, C.A.; Hudson, S.; Maine, L.L. Health Literacy Practices and Educational Competencies for Health Professionals: A Consensus Study. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suri, V.R.; Majid, S.; Chang, Y.-K.; Foo, S. Assessing the influence of health literacy on health information behaviors: A multi-domain skills-based approach. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, U.; Karter, A.J.; Liu, J.Y. The Literacy Divide: Health Literacy and the Use of an Internet- Based Patient Portal in an Integrated Health System—Results from the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). J. Health Commun. 2010, 15, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brach, C. The Journey to Become a Health Literate Organization: A Snapshot of Health System Improvement. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2017, 240, 203–237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tonkin-Crine, S.; Santer, M.; Leydon, G.M.; Murtagh, F.E.M.; Farrington, K.; Caskey, F.; Rayner, H.; Roderick, P. GPs’ views on managing advanced chronic kidney disease in primary care: A qualitative study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2015, 65, e469–e477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- von Wagner, C.; Steptoe, A.; Wolf, M.S.; Wardle, J. Health Literacy and Health Actions: A Review and a Framework From Health Psychology. Health Educ. Behav. 2009, 36, 860–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morony, S.; Flynn, M.; McCaffery, K.J.; Jansen, J.; Webster, A.C. Readability of Written Materials for CKD Patients: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015, 65, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brach, C.; Keller, D.; Hernandez, L.; Baur, C.; Parker, R.; Dreyer, B.; Schyve, P.; Lemerise, A.J.; Schillinger, D. Ten Attributes of Health Literate Health Care Organizations. NAM Perspect. 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, D.A.; Kynard-Amerson, C.S.; Wojciechowski, D.; Jacobs, M.; Lentine, K.L.; Schnitzler, M.; Peipert, J.D.; Waterman, A.D. Cultural competency of a mobile, customized patient education tool for improving potential kidney transplant recipients’ knowledge and decision-making. Clin. Transplant. 2017, 31, 2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teasdale, E.J.; Leydon, G.; Fraser, S.; Roderick, P.; Taal, M.W.; Tonkin-Crine, S. Patients’ Experiences After CKD Diagnosis: A Meta-ethnographic Study and Systematic Review. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2017, 70, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patients (n = 19) | Professionals (n = 22) # | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Age ^ | ||

| mean ± stdev (range) | 69.1 ± 12.2 (47–90) | mean ± stdev (range) | 42.6 ± 13.0 (21–63) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 7 (36.8) | Female sex, n (%) | 21 (95.5) |

| Educational level, n (%) | In step 3–4 of IM, profession, n (%) | ||

| Primary education | 6 (31.6) | Educator | 2 (9.1) |

| Lower secondary education | 4 (21.1) | E-learning educator | 1 (4.5) |

| Lower tertiary education | 8 (42.1) | Student Medicine | 2 (9.1) |

| Higher tertiary education | 1 (5.3) | Student Nursing | 2 (9.1) |

| Living situation, n (%) | In step 5 of IM, profession, n (%) | ||

| Alone | 7 (36.8) | General Practices | |

| With partner | 12 (63.2) | Specialized nurse | 3 (13.6) |

| Nationality n (%) | Nurse | 1(4.5) | |

| Dutch | 17 (89.4) | Nephrology clinics | |

| Other | 2 (10.6) | Specialized nurse | 1 (4.5) |

| Type of treatment, n (%) * | Nurse | 10 (45.5) | |

| Ambulatory (CKD-stage 2–4) ~ | 8 (42.1) | Working experience # | |

| Dialysis (CKD-stage 5) | 11 (57.9) | Years, mean±stdev | 14.1 ± 10.2 |

| Co-morbidities, n (%) | (range) | (2–39) | |

| Diabetes | 8 (42.4) | ||

| Hypertension | 7 (37.1) | ||

| Cardiovascular Diseases | 9 (47.7) | ||

| Other | 7 (37.1) | ||

| None | 2 (10.6) | ||

| Years of CKD | |||

| mean ± stdev (range) | 14.2 ± 14.3 (1–45) | ||

| Health literacy (AAHLS) | |||

| Total HL score, mean ± stdev (range) | 20.7 ± 2.9 (13–25) | ||

| Total Funct. HL+, mean ± stdev (range) | 6.9 ± 1.5 (3–9) | ||

| Total Comm. HL+, mean ± stdev (range) | 7.6 ± 1.6 (3–9) | ||

| Total Critical HL+, mean ± stdev (range) | 6.2 ± 1.6 (4–10) | ||

| Objective | Determinants | Experiences from Ambulatory Setting | Experiences from Dialysis Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improve CKD awareness | 1. HCPs create CKD awareness in LHL patients. 2. Patients are aware of having kidney problems. | Half of the patients are fully unaware Patients from GPs (n = 4) knew they had proteins in their urine, but were unaware of having CKD. Others had some awareness, but did not consider CKD dangerous. | Patients are fully aware All patients (n = 11) were fully aware of having CKD and its risks. Two patients stated they became aware when CKD was already severe. |

| Improve knowledge on CKD and self-management | 1. HCPs inform patients in simple language/with visual strategies. 2. HCPs check the patients’ understanding. 3. Patients understand (the symptoms and risks of) CKD. 4. Patients ask questions/clarification from the HCP. | Patients lack knowledge More than half of the patients (n = 4) lacked knowledge on CKD and CKD self-management. Patients shared problems with reading and understanding information (n = 3) and with asking HCPs questions (n = 5). The last was related to limited time and space to share personal issues during short consultations. | Patients struggle with the details Patients (n = 10) knew what CKD is and understood how self-management can stabilize CKD (n = 8). However, details on lifestyle and medication were, for many, difficult to understand (n = 7). Patients shared problems with reading and understanding information (n = 7) and with asking HCPs questions (n = 4). Frequent dialysis made asking questions easier. |

| Improve motivation and preparation of self-management | 1. HCPs apply shared decision making to decide on aims of self-management. 2. Patients are intrinsically motivated to self-manage their disease and treatment. 3. Patients share their personal needs regarding self-management with HCPs. | Not seeing the urgency to self-manage Half of the patients (n = 4) stated lifestyle and medication are important to improve health. Many were not very motivated to make self-management changes for CKD (n = 6), because they lacked symptoms or did not know how or why. If patients improved their lifestyle, they often did so because of co-morbidities (n = 5). Patients (n = 5) felt HCPs were in the lead during consultations. | Seeing importance, but complicated All patients (n = 11) stated lifestyle and medication are important and knew what they needed to do in their CKD self-management. Negative emotions (n = 6), and favoring quality of life over strict adherence (n = 6) were reasons not to change lifestyle sometimes. Half of the patients (n = 5) felt the HCPs were mainly in the lead in what they needed to do. |

| Teach competences to self-manage at home | 1. HCPs translate general self-management advice into action points. 2. HCPs respond to the patients’ problems. 3. Patients have the practical competence to improve lifestyle and medication. | CKD self-management is no explicit aim Few patients (n = 3) started to adopt lifestyle changes to stabilize CKD. Most (n = 6) gained competence helping them to live healthier in general, as a result of diabetes or hypertension. These patients said advice on lifestyle or medication were not always feasible (n = 4). | Unable to realize all needed changes All patients claimed to follow up at least some of the lifestyle and medication advice. Half (n = 6) said they gained the needed competence. However, it was simply too much, and HCPs do not always succeed in giving realistic advice or help to solve problems (n = 7). |

| Overcome barriers for self- management to maintain behaviors | 1. HCPs invite patients to share self-management barriers. 2. HCPs seek for solutions for barriers by applying shared decision making. 3. Patients recognize and solve barriers that negatively influence self-management. 4. Patients know strategies to maintain self-management. 5. Patients share their barriers and concerns with HCPs. | CKD self-management is no explicit aim Patients from GPs (n = 3) said they did not receive specific self-management advice to stabilize CKD. However, patients (n = 6) experienced barriers to self-management on a daily basis, either for diabetes, cardiovasular disease or CKD. Temptations (n = 5), lack of rewards (n = 2), age or mental problems (n = 3) were reasons to give up on self-management. Half of the patients (n = 4) felt that barriers were not discussed often. | Many barriers to maintaining changes All patients (n = 11) shared barriers in the maintenance of self-management. The burden of dialysis (n = 2), age or mental problems (n = 4), and the fact that their kidneys will never get better (n = 5), are all reasons to give up on self-management. Half of the patients (n = 6) felt that barriers were not discussed often. |

| Strengthen the social network | 1. HCPs involve the social network in consultation and treatment. 2. HCPs empower the social network to contribute to self-management. 3. Patients involve their social network in the treatment. | Social network is a bit important Most patients (n = 5) shared that they had the main responsibility in their lifestyle or medication, although others (n = 2) said their social network was mainly responsible. Patients (n = 3) did not always see the need to involve their social network in the treatment. | Social network is really important Half of the patients (n=6) indicated that a significant other was mainly in the lead in lifestyle or medication, although others (n = 2) said they had no support in their self-management. Some said that HCPs do not involve social networks enough (n = 4). |

| Patients (n = 4) | Healthcare Professionals (n = 17) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade for intervention # mean ± stdev | 7.75 ± 0.957 | Grade for intervention # mean ± stdev | 7.97 ± 0.910 |

Usability of the intervention (n)

| 0 1 3 | Fit to daily practice (n) Yes Partly No | 17 0 0 |

Complexity of the content (n)

| 0 3 1 | Complexity of workshop (n) Complicated Just right Easy | 0 12 5 |

Length (n)

| 2 2 0 | Length (n) Too long Good Too short | 0 10 7 |

| Self-reported effect (n) on: CKD understanding Understanding of consequences Understanding of lifestyle Lifestyle confidence Knowledge on consultation topics Consultation self-efficacy | 4 3 1 1 3 2 | Improved knowledge * mean ± stdev | 5.94 ± 0.854 |

| Usefulness other patients ˆ mean ± stdev | 4.00 ± 0.000 | Improved self-efficacy * mean ± stdev | 5.75 ± 1.000 |

| Usefullness significant others ˆ mean ± stdev | 3.75 ± 0.500 | Expected strategy use * mean ± stdev | 6.13 ± 0.619 |

| Objective | Determinants | Outcome Expectations | SocM # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improve awareness and knowledge on CKD self-management | HCPs know strategies to create CKD awareness in patients with LHL. HCPs inform CKD patients in simple language and with visual strategies. HCPs check the CKD patient’s understanding. Patients are aware of having CKD and what this diagnosis means (*). Patients understand (symptoms of) CKD and the long-term risks of CKD (*). Patients know important risk factors for developing more severe CKD (+). Patients know how self-management can stabilize kidney function (+). Patients ask for clarification and questions during consultations if needed. | Patients are more aware of CKD. Patients understand CKD better. Patients understand self-management of CKD better. Patients understand the long-term risks of CKD better. Patients feel more urgency to prevent further kidney deterioration. Patients discuss CKD better during consultations with HCPs. | Precontem-plation and contem-plation |

| Improve motivation and preparation of self-management | HCPs use health or life aims in goalsetting to motivate themselves to self-manage(+). HCPs apply shared decision making to decide on aims and self-management. Patients see the rewards of self-management for CKD and quality of life (*). Patients share their personal needs regarding self-management with HCPs. Patients prepare consultations to better discuss self-management (+). Patients feel confident to follow up self-management advice at home (+). Patients involve their social network in their self-management (*). | Patients know the exact goals of self-management of CKD. Patients contribute to decisions on self-management of CKD. Self-management goals are tailored to the patients’ needs. Patients are more confident to improve self-management. Patients are better able to adopt self-management in daily life. The social network helps to adopt self-management changes. | Preparation |

| Improve practical competences for self-management and to maintain behaviors on the long-term | HCPs translate general self-management advice into action points. HCPs ask about and respond to self-management barriers of the patient (+). HCPs seek solutions to barriers using shared decision making. Patients have the practical competences to improve lifestyle and medication adherence. Patients share their doubts regarding advice given by HCPs (+). Patients share their barriers and relapses with HCPs (+). Patients know strategies to prevent relapse of self-management changes. Patients recognize and solve barriers that negatively influence self-management (such as negative emotions, feasibility problems, relapse) (*). Patients seek additional help if they experience self-management barriers (+). | Patients gain practical skills for self-management of CKD. Patients are better at discussing barriers for self-management. Patients overcome barriers for maintenance of self-management. Patients maitain self-management changes in the long term. Patients deal better with emotions, infeasibility of advice and relapse. The social network supports patients in maintaining changes. | Action and maintenance |

| Improve the competences of HCPs | HCPs have awareness and knowledge of HL and its consequences. HCPs apply strategies to identify patients with LHL. HCPs involve the social network in consultation and treatment. HCPs empower the social network to contribute to self-management. HCPs know and apply tailored strategies to support patients with LHL during different stages of behavior change. These strategies are indicated behind the objectives above (informing patients in simple language, check understanding, using health or life aims, applying shared decision making, translating advice into action points, responding to barriers etc.) (*)(~). | HCPs have awareness and knowledge regarding health literacy. HCPs recognize patients with LHL. HCPs know effective strategies to support patients with LHL better and to involve the social network. HCPs apply the mentioned strategies effectively to support the patient during different stages of behavior change. | HCP support |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boonstra, M.D.; Reijneveld, S.A.; Navis, G.; Westerhuis, R.; de Winter, A.F. Co-Creation of a Multi-Component Health Literacy Intervention Targeting Both Patients with Mild to Severe Chronic Kidney Disease and Health Care Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13354. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413354

Boonstra MD, Reijneveld SA, Navis G, Westerhuis R, de Winter AF. Co-Creation of a Multi-Component Health Literacy Intervention Targeting Both Patients with Mild to Severe Chronic Kidney Disease and Health Care Professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):13354. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413354

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoonstra, Marco D., Sijmen A. Reijneveld, Gerjan Navis, Ralf Westerhuis, and Andrea F. de Winter. 2021. "Co-Creation of a Multi-Component Health Literacy Intervention Targeting Both Patients with Mild to Severe Chronic Kidney Disease and Health Care Professionals" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 13354. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413354

APA StyleBoonstra, M. D., Reijneveld, S. A., Navis, G., Westerhuis, R., & de Winter, A. F. (2021). Co-Creation of a Multi-Component Health Literacy Intervention Targeting Both Patients with Mild to Severe Chronic Kidney Disease and Health Care Professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 13354. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413354